Opium and heroin production and distribution

Government sources

Afghanistan Opium Winter Rapid Assessment 2010, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, February2010, [PDF, 3.5MB]

“Opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan has decreased by one third (36 per cent) over the past two years, from a record high of 193,000 ha in 2007 to 123,000 ha in 2009. Stabilization of the crop in 2010 is likely; if eventually confirmed, it would reinforce the progress made in the recent past.Most importantly in 2010 production may decrease. Recently, Afghan farmers have enjoyed bumper yields from their opium bulbs: 56 kg/ha in 2009, compared to around 10 kg/ha in the Golden Triangle. Bad weather during the current growing season may reduce the productivity of the crop this year and thus volume (tons) of opium produced in the country. This would continue the decline that has seen production fall from a massive 8,200 tons in 2007 to 6,900 tons last year.”

Afghanistan: 2007 Annual Opium Poppy Survey – Executive Summary, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, August 2007

“In 2007, Afghanistan cultivated 193,000 hectares of opium poppies, an increase of 17% over last year. The amount of Afghan land used for opium is now larger than the corresponding total for coca cultivation in Latin America (Colombia, Peru and Bolivia combined). Favourable weather conditions produced opium yields (42.5 kg per hectare) higher than last year (37.0 kg/ha). As a result, in 2007 Afghanistan produced an extraordinary 8,200 tons of opium (34% more than in 2006), becoming practically the exclusive supplier of the world’s deadliest drug (93% of the global opiates market). Leaving aside 19th century China, that had a population at that time 15 times larger than today’s Afghanistan, no other country in the world has ever produced narcotics on such a deadly scale.”

2007 World Drug Report, Office on Drugs and Crime, United Nations, June 2007.

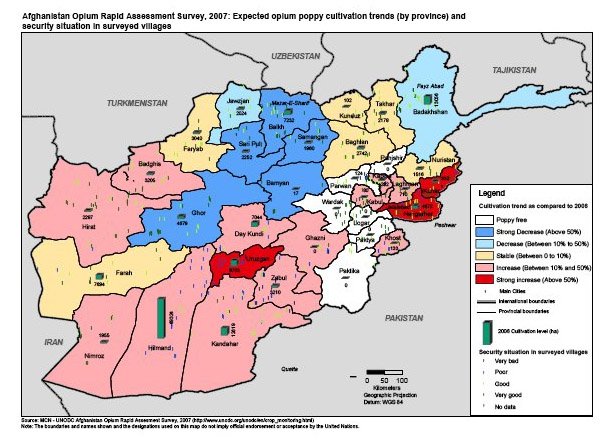

Afghanistan: Opium Winter Rapid Assessment Survey, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 5 March 2007

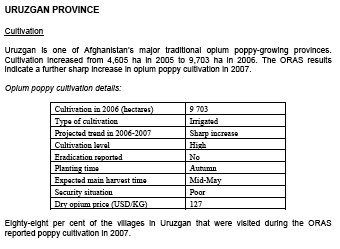

Detailed report, with provincial and district level information and excellent production maps. Reports a 379% increase in poppy production in Oruzgan province over 2005-6.

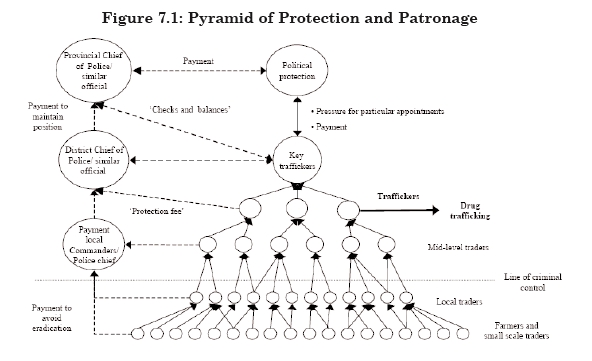

“The results show clear correlations between insurgency and illicit drug-related activities. While this is not new, Afghanistan seems to be the most obvious case in the world of how drug cultivation, refining and trafficking fund political violence, and vice versa.”

Source: Afghanistan: Opium Winter Rapid Assessment Survey, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 5 March 2007

Source: Afghanistan: Opium Winter Rapid Assessment Survey, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 5 March 2007

Afghanistan Opium Survey 2006, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

“There was considerable alarm when it was announced that opium cultivation in Afghanistan rose to 165,000 hectares in 2006, a 59% increase over 2005. This 6,100 tons of opium gives Afghanistan the dubious distinction of having nearly a monopoly of the world heroin market. Major traffickers, warlords and insurgents are reaping the profits of this bumper crop to spread instability, infiltrate public institutions, and enrich themselves. Afghanistan is moving from narcoeconomy to narco-state. While criminals prosper, the rest of society suffers. In Afghanistan, opium is choking development and democratization. The rule of the bullet and the bribe exists where there is no rule of law.”

Afghanistan’s Drug Industry: Structure, functioning, dynamics and implications for counter-narcotics policy, Doris Buddenberg and William A. Byrd (eds.), UN Office on drugs and Crime and the World Bank, November 2006.

Comprehensive study of the narco-economy and its associated criminal networks, based on fine-grained interviewing.

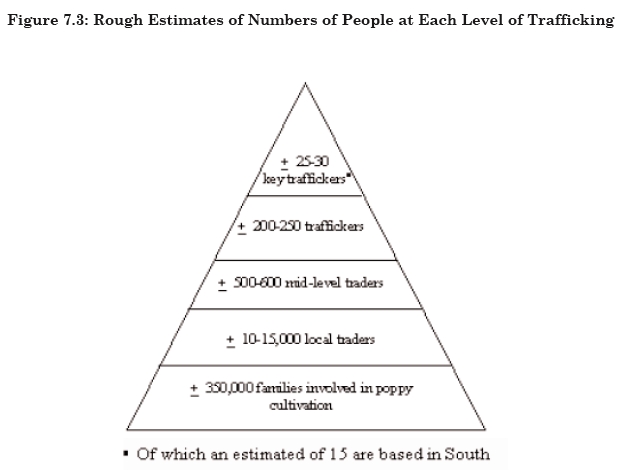

Drug trafficking and the development of organized crime in post-Taliban Afghanistan, Mark Shaw, in Afghanistan’s Drug Industry: Structure, functioning, dynamics and implications for counter-narcotics policy, Doris Buddenberg and William A. Byrd (eds.), UN Office on drugs and Crime and the World Bank, November 2006, pp 189-223.

“The consolidation in the number of key traffickers in the south appears to have been relatively rapid. Asked how many traffickers they believe there were in the past, local law enforcement officials suggest as many as 100. It is estimated currently that trafficking in the south, which also has important trafficking links to other parts of the country (most notably the north), is now controlled by at most an estimated 15 individuals and their trafficking groups. Law enforcement initiatives appear to have had the most consequences for small and medium-sized traders, forcing many of them out of the market, leaving only those with enough resources and political clout to protect themselves. ‘Police work in the south, such as it has occurred’, argues one enforcement official, ‘has been used to the advantage of a small number of key traffickers. I can’t catch them, otherwise they will catch me’.

“The approximately 15 key traffickers in the south appear to come from a variety of backgrounds and generally style themselves as businessmen. This is very different from the general conception of the warlord-trafficker. The key traffickers appear to be a mix of businessmen, former political players, religious figures, former NGO heads, and simple ‘bandits’. ‘What unites all of them’, according to an international official ‘is business acumen and a desire to get rich’. This consolidation has not been well documented, partly because there is little international media coverage of developments in the south, these developments have occurred under a high degree of security, and ongoing security problems make access difficult.

“In short, the south of Afghanistan is the center of the country’s illicit drug trafficking economy; it is the “gateway” for smuggling and the place where the major criminal groups, with strong connections to the center, have consolidated.”

The Opium Economy in Afghanistan: An International Problem, United Nations Office On Drugs And Crime, 2003

Very detailed survey report. “Last year’s opium poppy harvest was among the highest in the country’s history. Why is the international presence in Afghanistan not able to bring under control a phenomenon connected to international terrorism and organized crime? Why is the central Government in Kabul not able to enforce the ban on opium cultivation as effectively as the Taliban regime did in 2000-01? There are no simple answers to these questions. The opium economy of Afghanistan is an intensely complex phenomenon. In the past, it reached deeply into the political structure, civil society and economy of the country.”

Analysis

UN forecasts ‘stable’ Afghan opium crop, Veronika Oleksyn, AP, 10 February 2010

After a major drop over the past two years, Afghanistan’s opium cultivation is unlikely to rise or fall dramatically in 2010, a U.N. report said. The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime’s annual winter survey said bad weather may lead to a decrease in opium production but warned the country could see fewer poppy-free provinces.

Afghanistan supplies 90 percent of the world’s opium, the main ingredient in heroin, and the highly lucrative crop has helped finance insurgents and fueled corruption. In September, the Vienna-based UNODC said Afghanistan was still producing 6,900 tons of opium a year, 1,900 tons more than the world consumes. In 2007, production stood at a staggering 8,200 tons.

Efforts to curb Afghan opium crop fail this year – U.N., Peter Graff, Reuters India, 10 February 2010

Afghan opium production in significant decline, UNODC, 2 September 2009

Opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan is down 22 per cent, opium production is down 10 per cent, while prices are at a 10 year low. The number of opium poppy-free provinces has increased from 18 to 20 out of a total number of 34, and more drugs are being seized as a result of more robust counter-narcotics operations by Afghan and NATO forces.

U.N. Sees Afghan Drug Cartels Emerging, Richard A. Oppel, NYT, 1st September 2009

Though the Afghan opium harvest has declined for the second consecutive year, a new United Nations report says, there is growing evidence that some Afghan insurgent forces are becoming “narco-cartels” — similar to anti-government guerrilla groups in Colombia — that view drug profits as more important than ideology.

Papaverteelt/poppy cultivation, opium, Uruzgan weblog

Excellent extensive weblog collection on opium production and its political and security consequences, in Dutch and English. Updating ended mid-2007, but the site remains an important resource. [See Babel Fish for Dutch-English translation.]

Frontiers and Wars: the Opium Economy in Afghanistan, Jonathan Goodhand, Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 5 no. 2, April 2005.

Project coordinator: Richard Tanter

Additional research: Ronald Li

Updated: 10 February 2010