MICHAEL ROACH

AUGUST 6 2022

I. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, Michael Roach provides a remarkable account of multigenerational involvement in nuclear war, starting with a previously unpublished photo of the starboard nose of the Enola Gay bomber that delivered the first atomic bomb and returned to Tinian airfield, showing the inscription “First Atomic Bomb – Hiroshima – August 6, 1945.” He concludes: “The prospect of real atomic warfare in Japan during the 1940’s and potential atomic warfare in Korea during the 1960’s brought the lives of my father and myself together historically, but we came away from the experience with completely different conclusions. He was very proud of his service in helping to carry out a small part in the atomic bombing missions over Japan that ended the war. On the other hand, I am still troubled by the thought that I came so close to such a momentous decision as personally detonating an atomic bomb in a densely populated metropolis on so little historical knowledge and justification. That concern has sent me on a lifetime of learning history and trying to create a more just and equitable world.”

Michael Roach is a retired renewable energy manager and lives in a small Wisconsin farm town surrounded by vast green fields of corn and soybeans. He is currently writing a history of wheat culture using commodity chain analysis. His current research is part of a larger project that examines the history of illumination and power technologies from 18th century whale oil to modern microgrids. He also volunteers his time to assist in the reconstruction of Ukraine using ultra energy efficient modular multifamily housing powered by solar microgrids. He served in US Forces Korea as an Atomic Demolition Munitions engineer in 1968.

This essay is published simultaneously by APLN here and by RECNA-Nagasaki University here with summary in Japanese here.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

This report is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here.

Banner image: Enola Gay, starboard side, Roach family archives.

NAPSNET POLICY FORUM BY MICHAEL ROACH

THE CROSSROADS OF ATOMIC WARFARE IN ONE FAMILY

AUGUST 6 2022

“Fate” is just another name for history where the life paths of different individuals cross, often in unique but related connections. In our family, atomic warfare is one of the historical connections between my father and myself.

Kenneth Roach, Radar Station Maintenance, Saipan, 1945

(Collection of Kenneth Roach)

My Father’s Path into Atomic Warfare

For five generations, our family has resided in Janesville, Wisconsin. The city is a typical 20th century working class industrial town now surrounded by vast fields of corn and soybeans. One of the city’s claims to fame is that it was the home to the Parker Pen Company. My father, Kenneth Roach, worked at Parker for 44 years, from the time he was 19 years old to age 63 when he retired. He received a five year leave when he served in the Signal Corps of the U.S. Army from 1942 until 1947. The Parker Pen Company has long gone from the city although their modern-looking factory building still stands. The corporate remnant of the company is now a part of some conglomerate holding company and pen production is optimized at some distant location.

When World War II started, my father volunteered for service at the age of 23. His military occupational specialty was in radar equipment maintenance. Ever since he was a youth, he had a fascination with electricity and radio technology. He made crystal radios from scratch. When the Army recognized his interest and enthusiasm, he was channeled into two years of advanced training in the new secret of radar technology. His military occupational specialty was in the technical maintenance of radar stations.

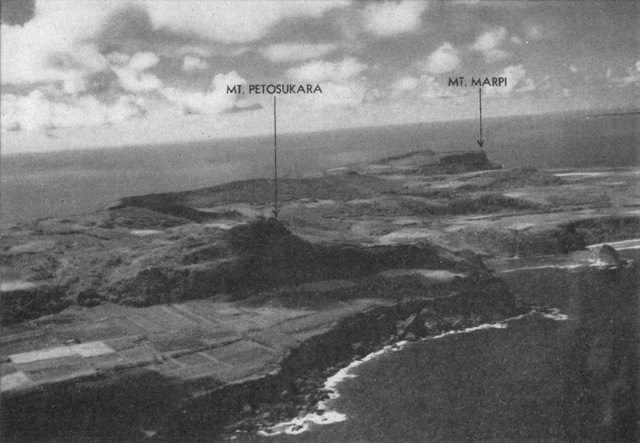

North End of Saipan, Mt. Petosukara, Radar Station, 1945 (Source Internet)

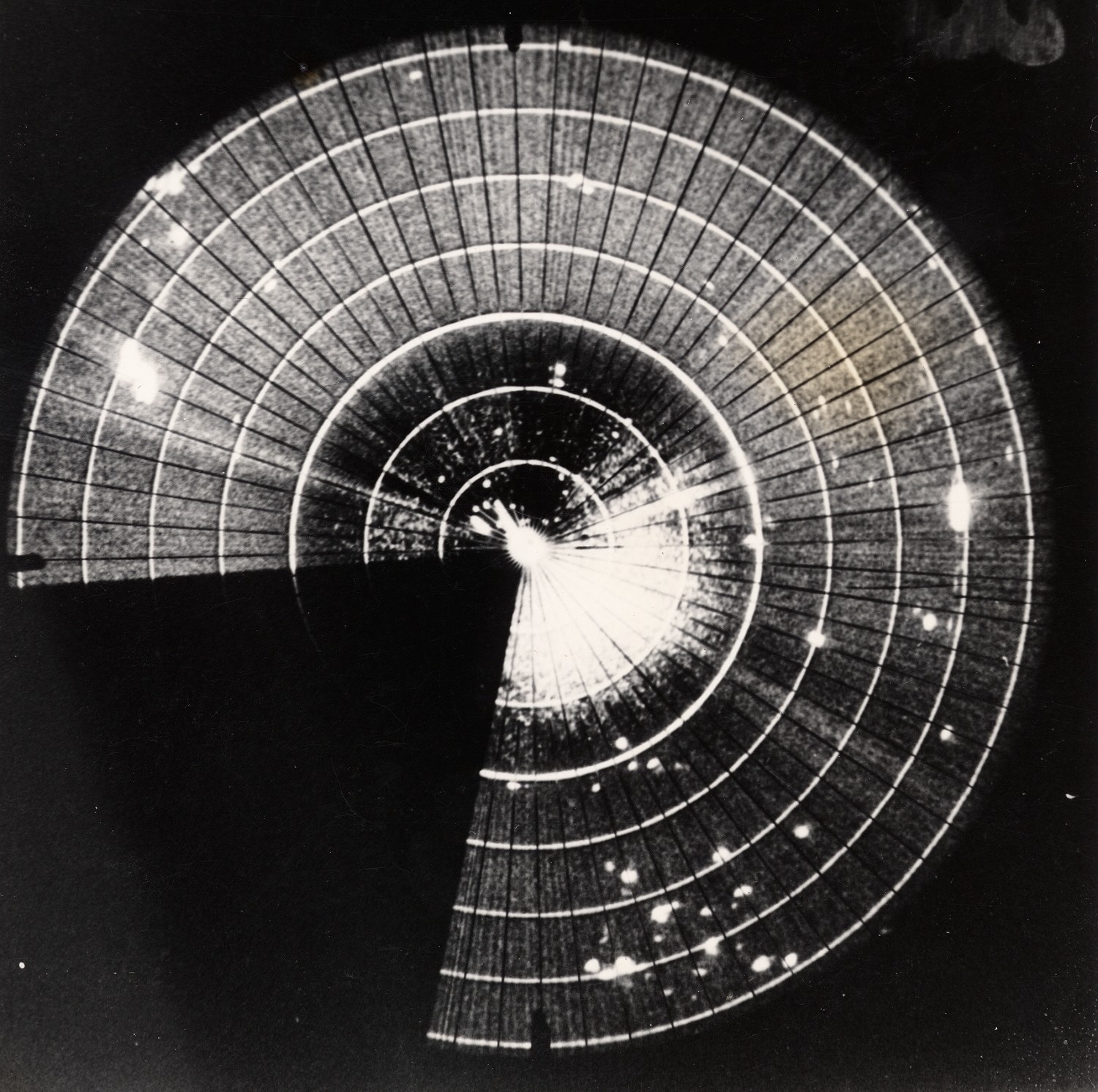

Layout of Radar Station, Mt. Petosukara, Saipan, 1945

(Collection of Kenneth Roach)

Radar Screen, U.S. Army Signal Corp., Saipan, 1945

(Collection of Kenneth Roach)

When Saipan was invaded by American troops in June of 1944, he was assigned to the island even before the last pockets of Japanese military resistance were overcome. For weeks, civilians were still jumping off of the cliffs. Whole families plunged to their death on the rocks for fear of the terrible Americans. Japanese war ideology and the Japanese military’s enforcement of “no surrender,” sacrificed many helpless people. Whenever my father mentioned his military service, this needless mass death of civilians still upset him.

When my father arrived on Saipan, the American Army immediately took over Japanese communications facilities on Mt. Petosukara (Mt. Topatchau) and installed advanced American radar equipment. His unit’s initial mission was to provide early warning of approaching Japanese fighter planes. The radar station could see out about 150 miles in a semi-circular arc north and northwest of the island. B-29s were piling up on Saipan and Tinian as part of General Le May’s air assault on Japanese cities. My father said that he and his fellow radar workers were well aware of the strategic importance of 509th Bomber Command and their needed radar support. As soon as the Japanese fighter threat had been suppressed, the radar mission turned to tracking the almost continuous stream of out-going and returning B-29 Superfortresses.

“Enola Gay” After Bomb Run Over Hiroshima on Tarmac, Tinian (Source: Internet)

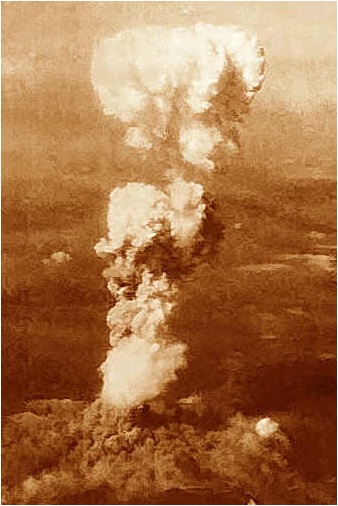

Hiroshima Bombing, August 6, 1945

(Source: The Nuclear World Project)

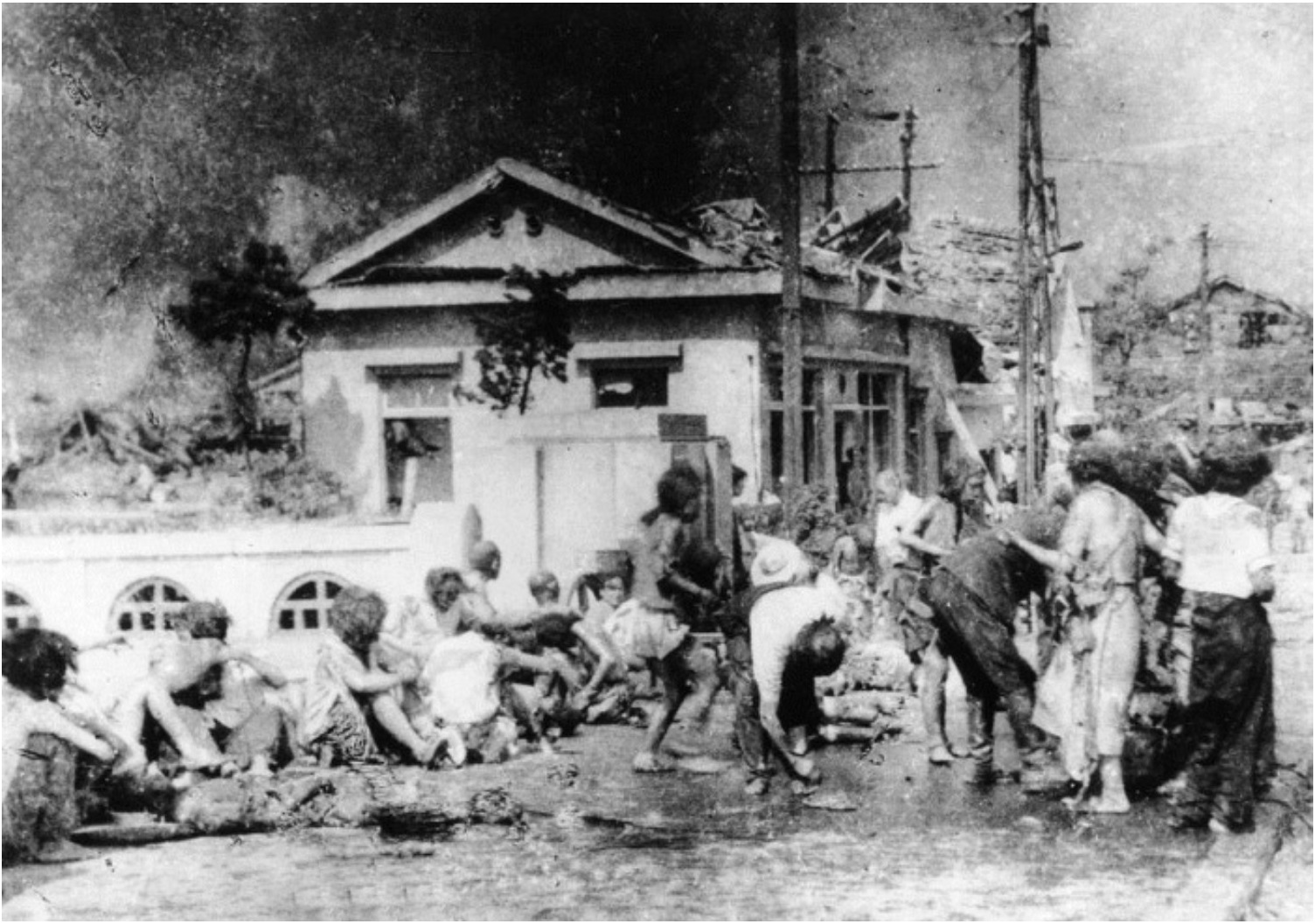

Japanese Civilian Survivors of Hiroshima Atomic Bomb

(Source: Internet)

The Flight of the Enola Gay

By August of 1945, almost every day involved air traffic control of many planes going out in large formations. In the first week of August, scuttlebutt involving the 509th Bomber Command spread concerning a new secret weapon, but no one (except the small group of fliers and commanders directly participating in the secret mission) knew any of the details of what was coming in the next days, other than security was extra high.

It was only after the B-29 crews dropped the first bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki did ground support crews and radar operators learn what the true missions were for all the secrecy surrounding the “weather recon” flights. As soon as Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan and the Japanese Army stopped fighting, American troops on Saipan and Tinian were invited, as units, to view the Enola Gay parked on the tarmac. It was a small reward for the troops that had been fighting for years, but my father said that it was one of the most memorable experiences in his life.

In the 1950’s, my father, like so many other veterans, never volunteered much personal information about his military career. It was only when the children in our family looked through my parent’s photo albums did the issue of “what did you do in the war” ever come up. His photos were all small Kodak snapshots in black and white of men in uniforms with tents and tropical scenery in the background.

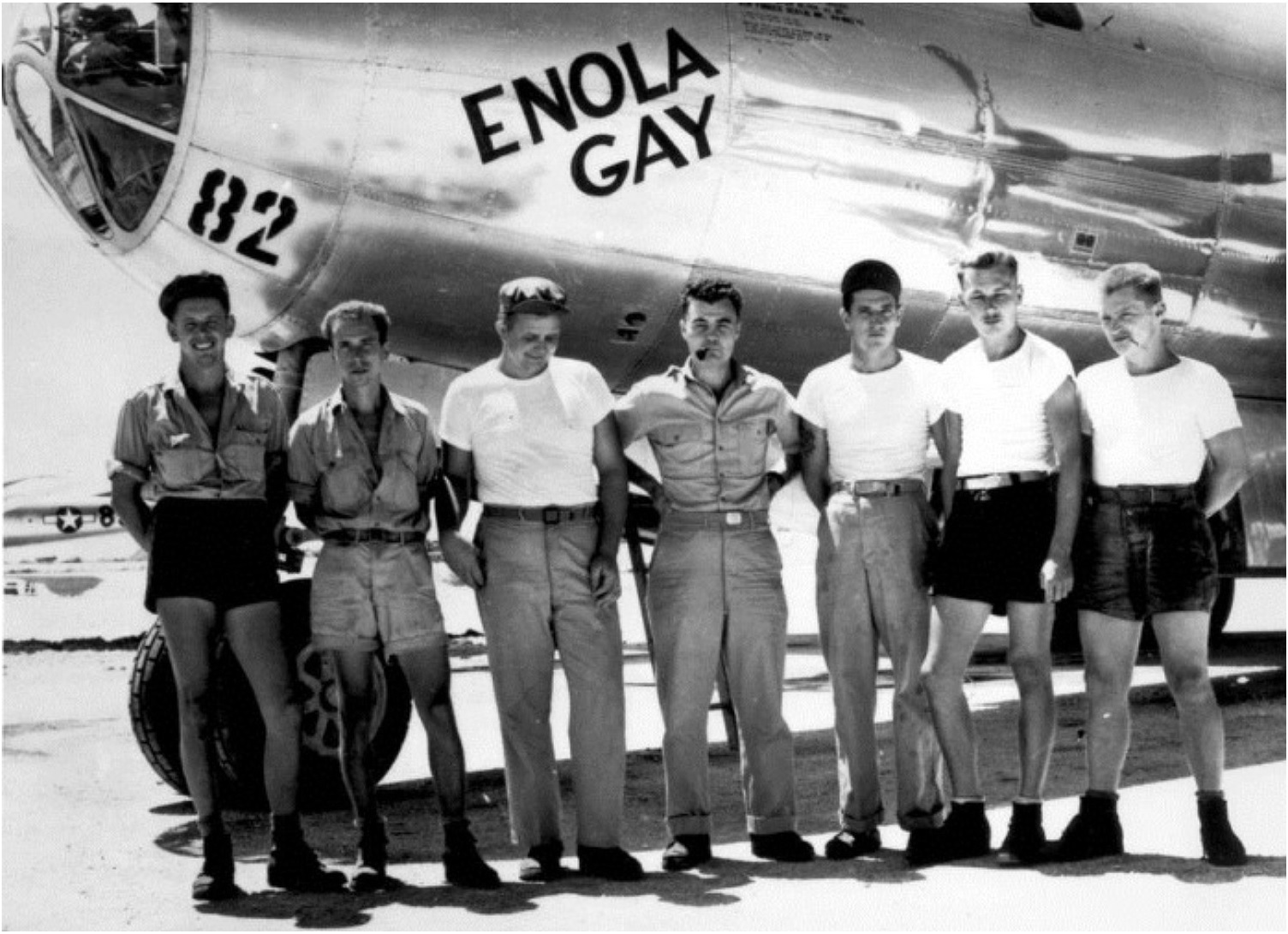

Flight Crew of Enola Gay Hiroshima Mission

Flight Crew of Enola Gay Hiroshima Mission

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr. – Pilot and Aircraft Commander (center)

Tibbets Was Only 29 Years Old at the Time of the Hiroshima Mission

(Source: Wikipedia)

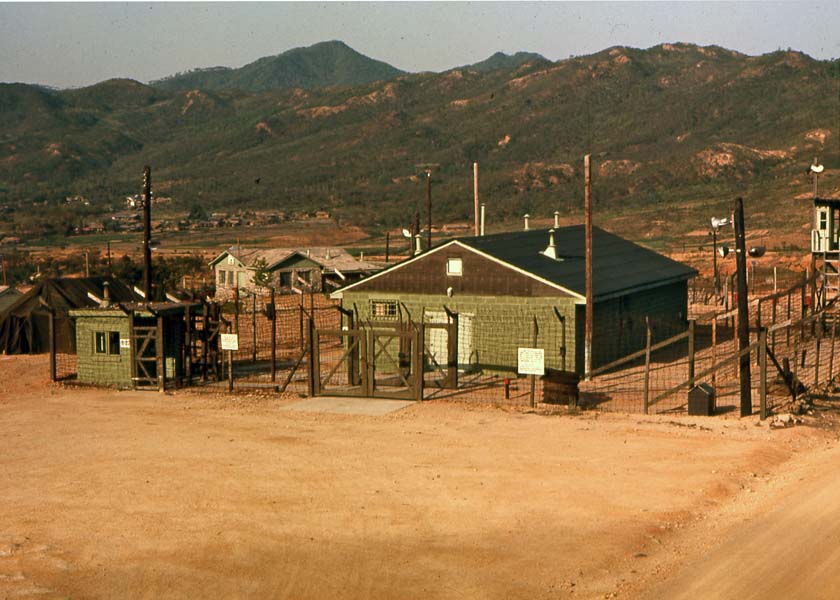

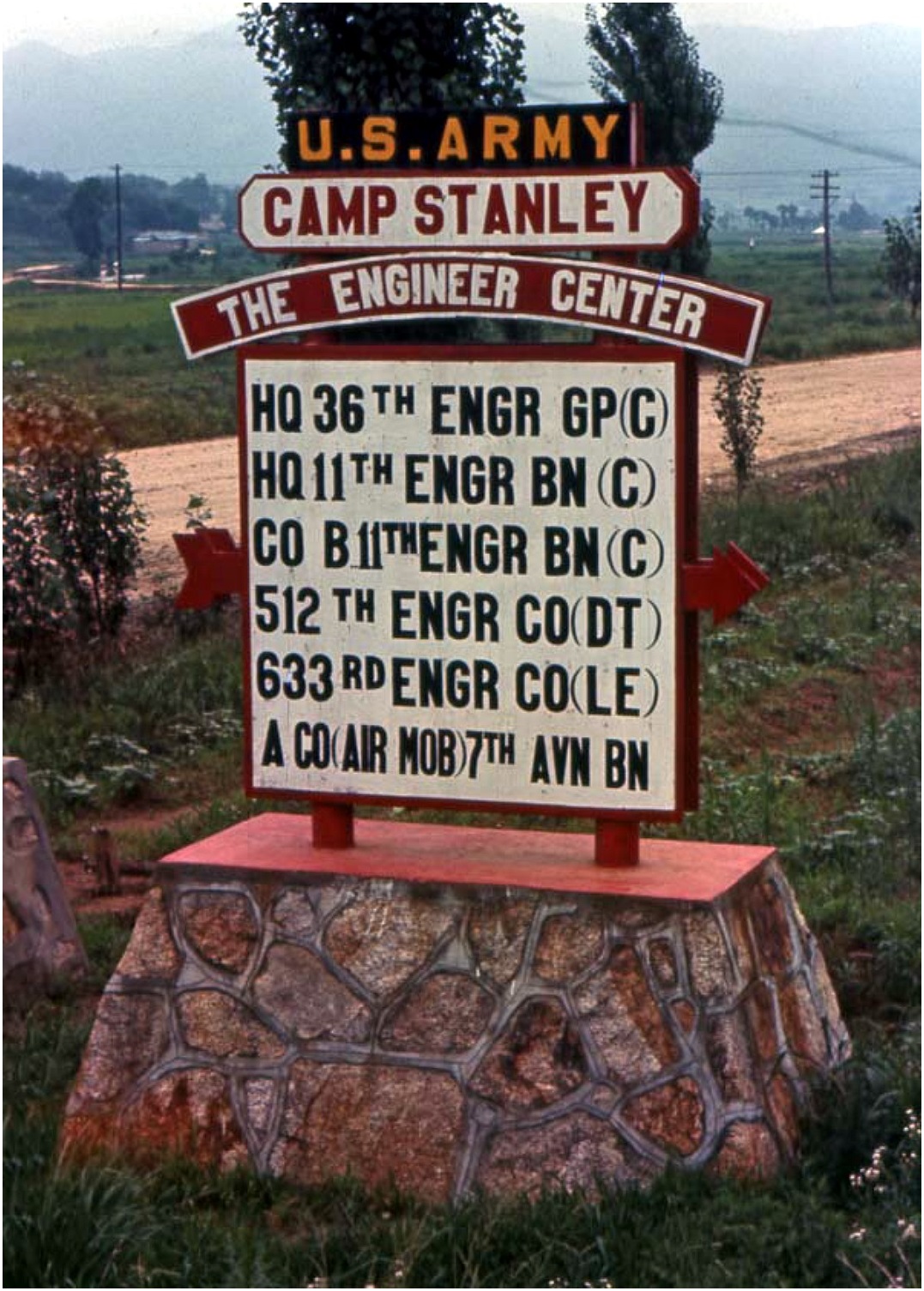

The “Monkey House” ADM Training Facility

The “Monkey House” ADM Training Facility

Camp Stanley, South Korea, 1968

(Source, personal photo, Michael Roach)

My Path into Atomic Warfare

I am the oldest son in a family of 11 children. I graduated from high school in 1966 only one month after I had turned 18. The Vietnam War was raging and 400-500 American soldiers died every week. The war loomed over our lives while Walter Cronkite chronicled its daily bloody passage. In our home town, many parents encouraged their sons to volunteer for the war, just like previous generations of American patriots doing their duty for our country. High school advisors recommended that local blue-collar boys should join up because they could learn a “skill.” Unfortunately for many local boys, the skill that they learned was how to fire an M-16 rifle.

The smart, upper middle-class students in our high school class sailed off to college on deferments and most of them avoided any military service unless they flunked out and the Draft Board nabbed them. Some of the local college-bound students would later learn the elements of history and politics and become campus anti-war protesters.

For those of us that did not go to college, the life choices in the mid-1960’s were quite limited. You could drink yourself into alcoholic oblivion and garner a 4-F deferment if you had the stamina for ultra-high alcohol consumption and didn’t die in a drunk driving crash. A more popular choice was to go directly from high school to work in the local General Motors Assembly Plant making cars and trucks. Over 7,000 workers kept the factory going full blast on two shifts during the war boom years. Working on the assembly line at “the Plant” gave young men a taste of real money. But, the worker paradise for these young men was a short illusion. As soon as they turned 19 years old, the local Draft Board immediately drafted them and a month later they were in boot camp. Three months later and they were slopping around in rice paddies in Vietnam with Viet Cong soldiers shooting at them.

In my circle of boyhood friends, 3 died in combat, 2 were seriously wounded, 1 suffered from Agent Orange for a lifetime, 1 got a National Guard deferment because of the influence of his rich father. Another went to college and when that deferment was eliminated, he got a draft number that kept him out of military service. I volunteered for a 3-year hitch in the Army. I was not for or against the war, I only wanted to get out of the confines of a McCarthyite small town social environment. Another factor in my choice of military occupation was that I grew up in the “Atomic Age.” Continuous above-ground atomic bomb tests, the “missile race,” the “Cuban crisis” and the apparent need to build fallout shelters in the backyard all portended that atomic warfare was not only a possibility but rather a probability. Even naive and historically ignorant Midwest teenagers like myself could perceive that our country was on the precipice of a deadly abyss. The only thing that seemed to diminish the threat of atomic warfare was the actual old-time ground war grinding away in Vietnam and blaring in the daily newspaper headlines and evening TV news programs.

Michael Roach (right) with ADM Platoon Members on Pass, Uijeongbu, South Korea, 1968

Michael Roach (right) with ADM Platoon Members on Pass, Uijeongbu, South Korea, 1968

(Source: personal collection, Michael Roach)

Joining An Atomic Demolition Munitions Platoon

When I went to the military recruiters, I told them that I wanted to be a pilot, but they kindly informed me that only college graduates qualified for such exalted positions, unless I wanted fly a helicopter. I asked about explosives, since the guys in the movies that blew up dams and munitions factories seemed very heroic. When he offered Atomic Demolition Munitions, I knew that I had found the right fit. I had no real understanding of what the position entailed, either personally or socially. But the job seemed somehow “skilled.” I signed up and was gone within a month. I spent one and a half years in all sorts of military training, including building Bailey bridges and watching endless movies of the effects of atomic bombs. When I finished training, I was assigned to Italy to complete extreme skiing training in the Alps. But my records got mixed up and I ended up going to South Korea.

In the 1960’s, the U.S. military actively pursued a defensive strategy based on the deployment of tactical atomic bombs. Their main utility was to temporarily (two weeks or so) block armored columns of overwhelming Soviet forces or Chinese-North Koreans. Most of the targeted zones were in densely populated areas, so anticipated civilian casualties were high. But that was just a collateral cost necessary for strategic military victory. At the start of the Korean War in 1950, North Korean tanks poured down the “bowling alley,” the 50-mile valley running north to south from the North Korean border to the heart of Seoul.

Two war plans existed for the defense of Seoul. In the “U.N. Plan,” a joint US-Korean version, a perimeter arc extending northward out 10-15 miles from the Capital was set as the primary line of defense. Three approaches (the coastal, the bowling alley and the northeastern mountain valleys) terminated at Seoul. When conventional forces could no longer hold out, tactical atomic bombs were to be detonated at strategic positions to create impassable defiles contaminated with radioactive debris. Our Atomic Demolition Munitions (ADM) unit’s mission was to create these atomic dead zones.

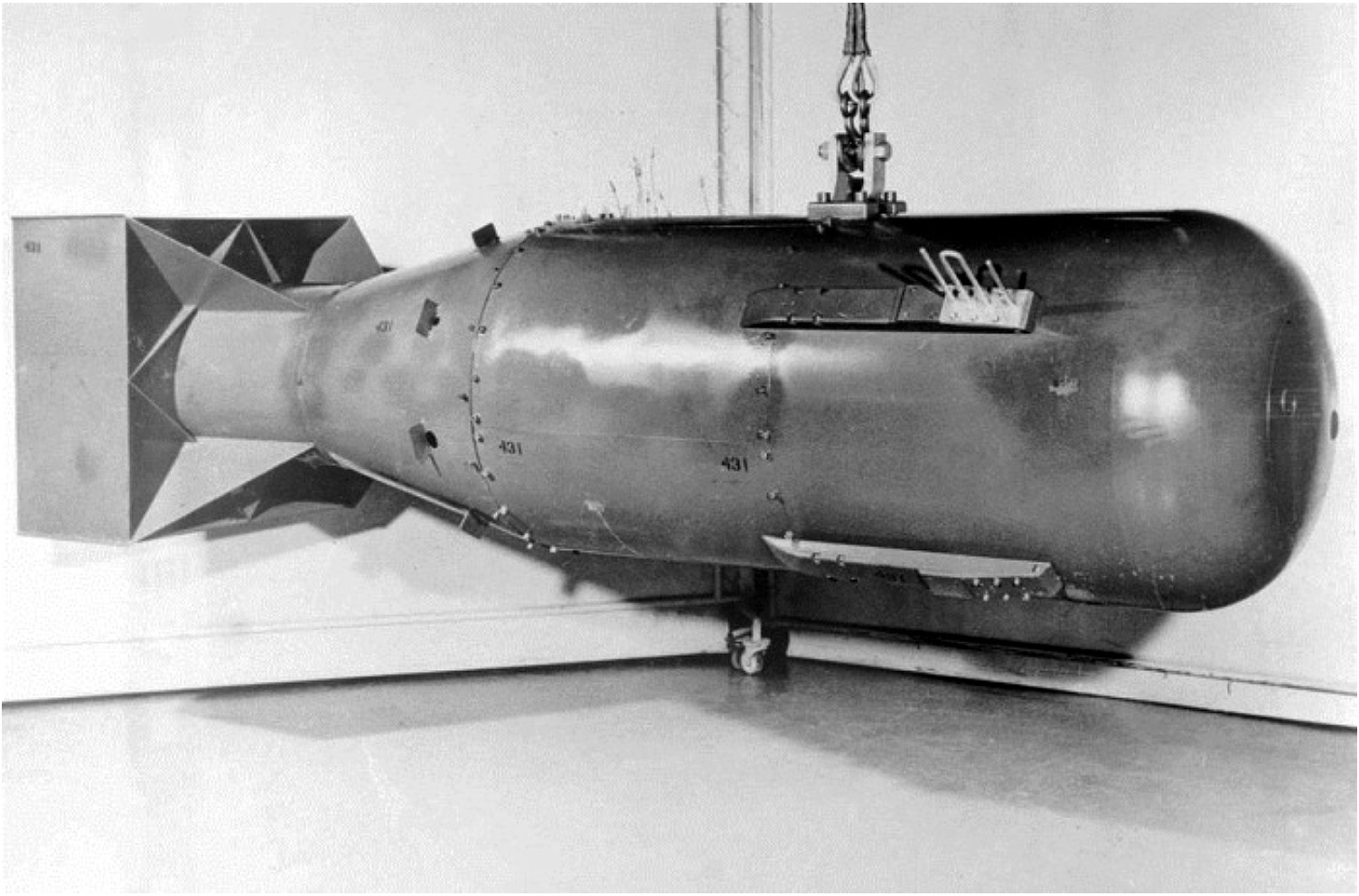

“Little Boy” – First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945

9,700 Pounds, 10 Feet Long, 28 Inches Diameter, 15 Kilotons of TNT Explosive Power

((Source: Wikipedia)

Transport Container for ADM “Device” (Training Dummy)

Transport Container for ADM “Device” (Training Dummy)

59 Pounds, About 2 Feet Long, Variable Yield of 1-10 Kilotons of TNT

(Source: Wikipedia)

The Internal Components of an ADM “Device”

The Internal Components of an ADM “Device”

(Source: Wikipedia)

An ADM “device” looks like a huge. .45 caliber bullet measuring about two feet long and almost as wide. It weighed 59 pounds and with a parachute backpack it was just over 90 pounds. An ADM explosion was the equivalent of at least 10 kilotons of TNT. Our job was to hand deliver one of these bombs to very specific coordinates and “escape and evade.” Our targets included creating large defiles, destroying industrial scale bridges and breaking up airport runways. All of our targets were “defensive” in that the destruction caused by the ADM bomb was intended to prevent the enemy from using the targeted facilities for a long time if the facilities were captured.

One Segment of the Atomic Warfare Chain of Command in the 1960’s

One Segment of the Atomic Warfare Chain of Command in the 1960’s

(Source: personal photo, Michael Roach)

Our Platoon was stationed at Camp Stanley just outside of Uijeongbu, about 10 miles north of Seoul. This defensive plan was approved by the Korean political and military leadership, but it was of little real defensive deterrence. Following Stalin’s battlefield strategy of only advancing and never retreating (even for tactical reasons), the North Korean military commanders would have just sent their troops through the radiated zones without any regard for the safety of their soldiers.

The top secret “American Plan” was stamped “No Foreign Eyes.” This plan was designed to blow up the large bridges spanning the Han River at Seoul. This plan abandoned the symbols South Korean authority on the north shore of the river and, therefore, imperiled the legitimacy of the regime. With the big bridges blown by tactical atomic bombs, the American military could use the wide river as a far more effective barrier to further advances by NK forces, especially tanks.

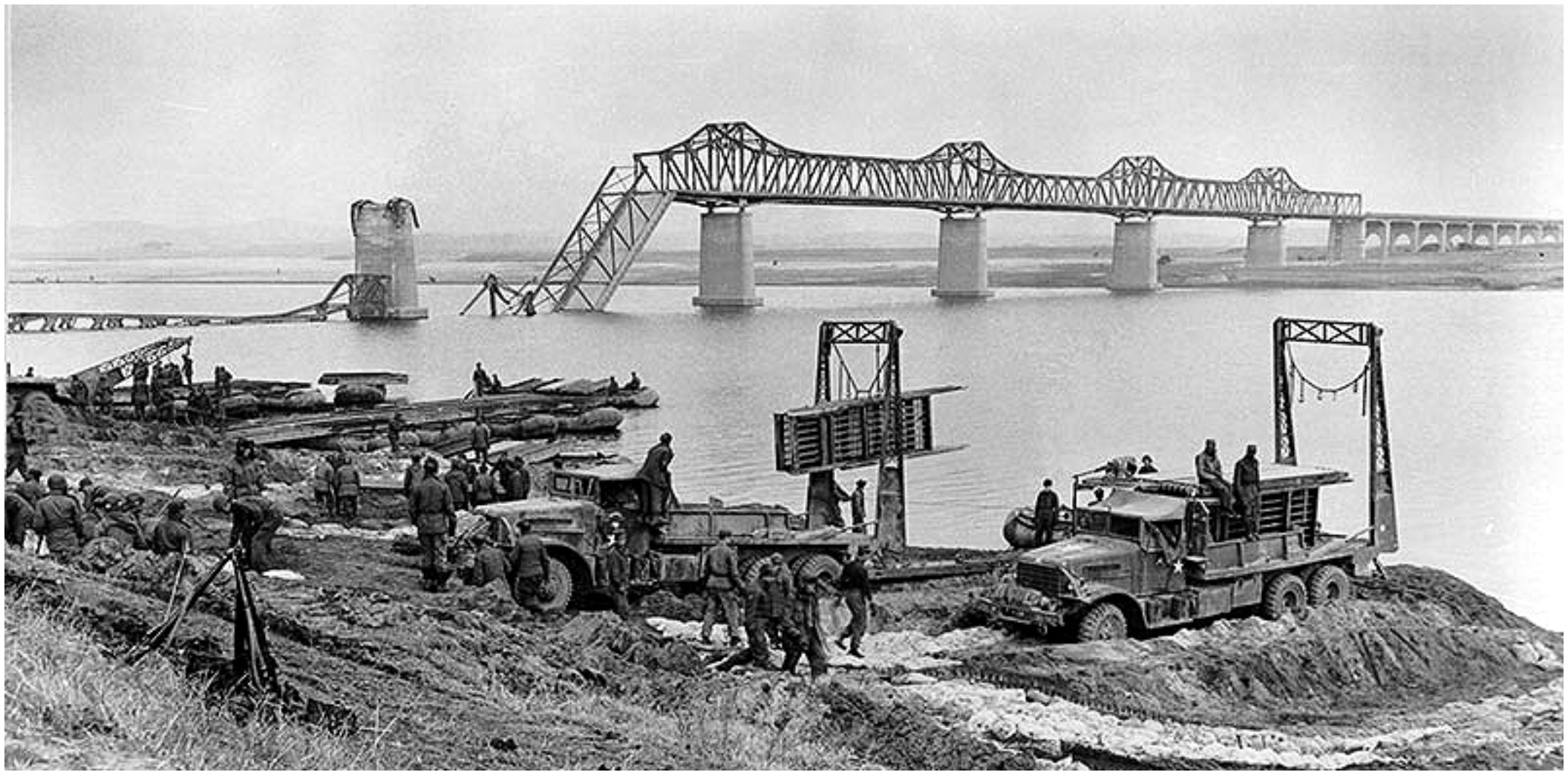

North Korean troops invaded South Korea on June 25th 1950. South Korea was totally unprepared and their troops and civilians quickly retreated from the front. In Seoul, escapees jammed across the Han River Bridge, one of the only ways to cross the mile-wide river. On June 28th, South Korean authorities decided to blow up the bridge to stop the North Korean armored advance. Unfortunately, the unannounced demolition only destroyed two spans of the bridge and partially damaged one footing at the cost of killing and wounding hundreds of troops and civilians.

After the war ended, American military planners decided to use ADM bombs to destroy the whole bridge and the all of the footers. In the 1960’s, our ADM mission was to destroy three major bridges crossing the Han River. Instead of killing only hundreds of people, the detonation of a tactical atomic bomb would have killed tens of thousands of people during a wartime panic evacuation. This destruction of a major bridge was one of our ADM missions.

On June 28, 1950, South Korean Authorities Decided to Blow Up the Han River Bridge, But the Explosion Only Partially Damaged the Bridge. In the 1960s, the Use of Tactical Atomic Bombs (ADMs) Were Designed to Destroy the Whole Bridge, Including the Footers..

(Source: Robert Neff Collection)

Part of my job in the ADM unit was to monitor target files and assist our teams in the correct placement of “devices” according to the war plan. In the post-detonation damage assessment sections, four sectors were reviewed: first, military assets and facilities; second, military personnel; third, civilian assets and facilities; and, finally, civilian casualties. If we had detonated even one bomb for a bridge, civilian casualties were estimated to be comparable to those of Hiroshima, on the order of 70-80,000 deaths just from initial blast and thermal radiation.

In our ADM platoon, we were organized in small teams to be able to deliver multiple weapons simultaneously on command. We were the last link in a long chain of command from the President to Commander-in-Chief Pacific to Commander of I Corps Korea to the 36th Engineering Group to the 11th Engineering Battalion to our “B” Company and, finally, to our ADM platoon. We were the human beings who actually initiated a “device” and started a chain reaction resulting in an atomic explosion of at least 10 kilotons. At the time (1968-69), our platoon members recognized that we were, in fact, suicide bombers because we hand-delivered “devices” and could not abandon them, if they were set for 15 minutes or less, which they always were. When you are a 20-year-old Midwestern small town boy, your own life seemed easily disposable, especially for a heroic mission.

Ground Crew Members of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, 509th Composite Group Awaiting General Spaatz’s Arrival for Ceremony Celebrating the Safe Return of the Enola Gay After Completing Its Mission of Dropping the First Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945

(Source: Atomic Heritage Foundation & National Museum of Nuclear Science & History)

Sharing War Stories with My Father

It was only after I completed my three-year term of Army duty and went to college did I really reflect on my military service and the consequences of actually carrying out our bombing missions of tactical atomic warfare. From our ADM target profiles, it was clear the most of the radiation created by detonating atomic bombs in Korea would result in spreading a wide swath of the radiation over Japan. I didn’t think that the Japanese would appreciate being atomic warfare guinea pigs a second time.

That concern sent me on many years of studying history and politics so that I could comprehend how I got myself in such a terrible position with potentially monstrous consequences. Whenever I mentioned any moral concerns to my father regarding my military service as an atomic warfare warrior, he expressed no similar questioning or qualms over his role in facilitating the flight of the Enola Gay mission. He referred to the viciousness of Japanese troops, their refusal to surrender even under doomed circumstances and their role in getting civilians to jump off of the cliffs in Saipan as ample justification for actually using an atomic bomb. In his eyes, the atomic bombings were totally justified and helped to save hundreds of thousands of American troops from future bloodbaths of fighting on the Japanese homeland.

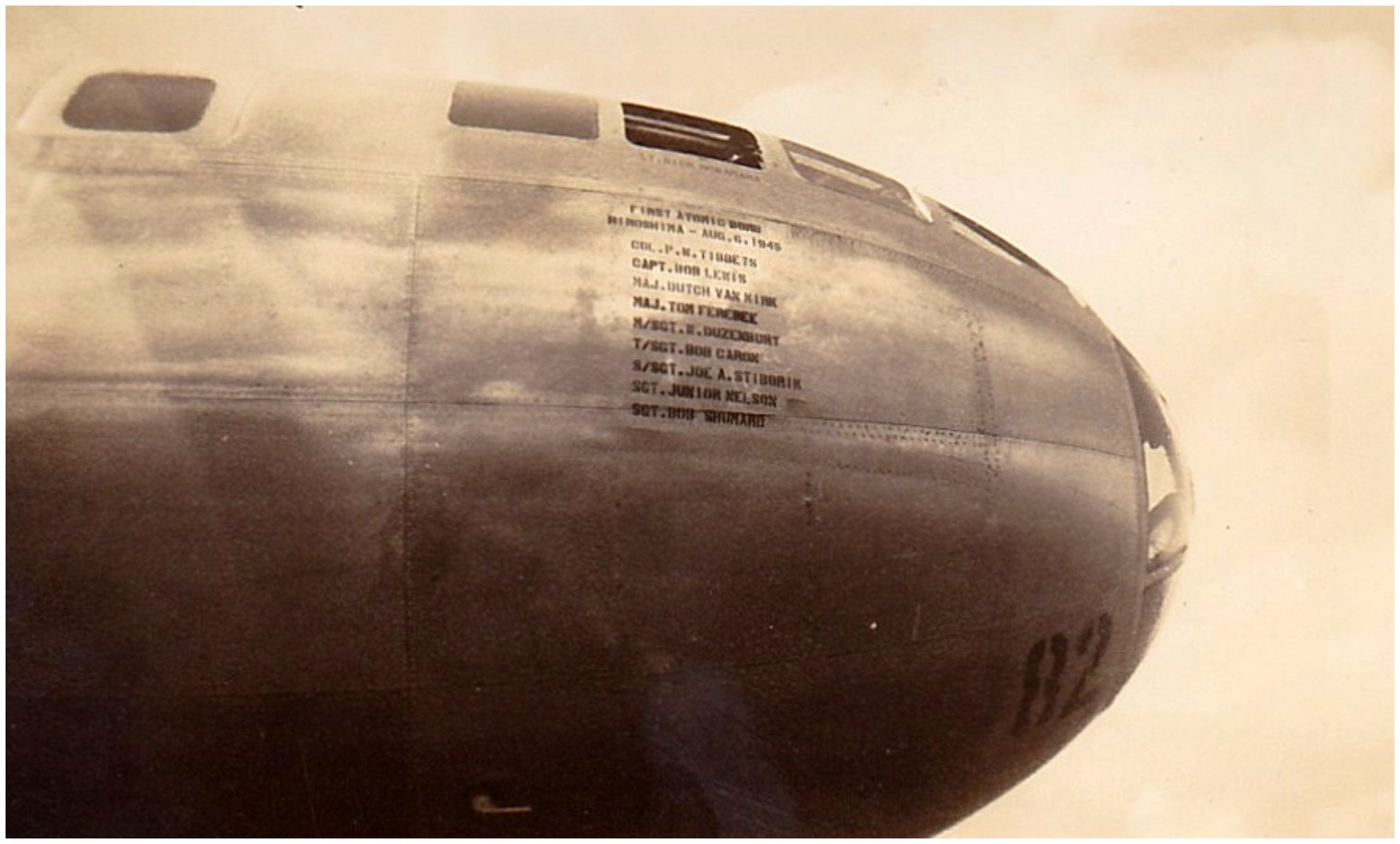

Rare Photo of the Starboard Side of the “Enola Gay” Parked on the Tarmac in Tinian, 1945

Rare Photo of the Starboard Side of the “Enola Gay” Parked on the Tarmac in Tinian, 1945

(Source: collection of Kenneth Roach)

Subsequent to the bombing of Nagasaki and the end of fighting, each unit on Saipan and Tinian was invited to come and visit the Enola Gay. When my father’s signal unit was invited to come down to Tinian and view “the plane that ended the war”, he came away with one photograph of the starboard side of the nose. Most photos of the Enola Gay only show the port side that displays the ship’s name in big letters. I don’t know if he took the picture or if they were handouts by the Army PR people. My father died before I could clarify that question. I made a digital scan of the picture, but the original disappeared when my parent’s house was cleared out after their deaths.

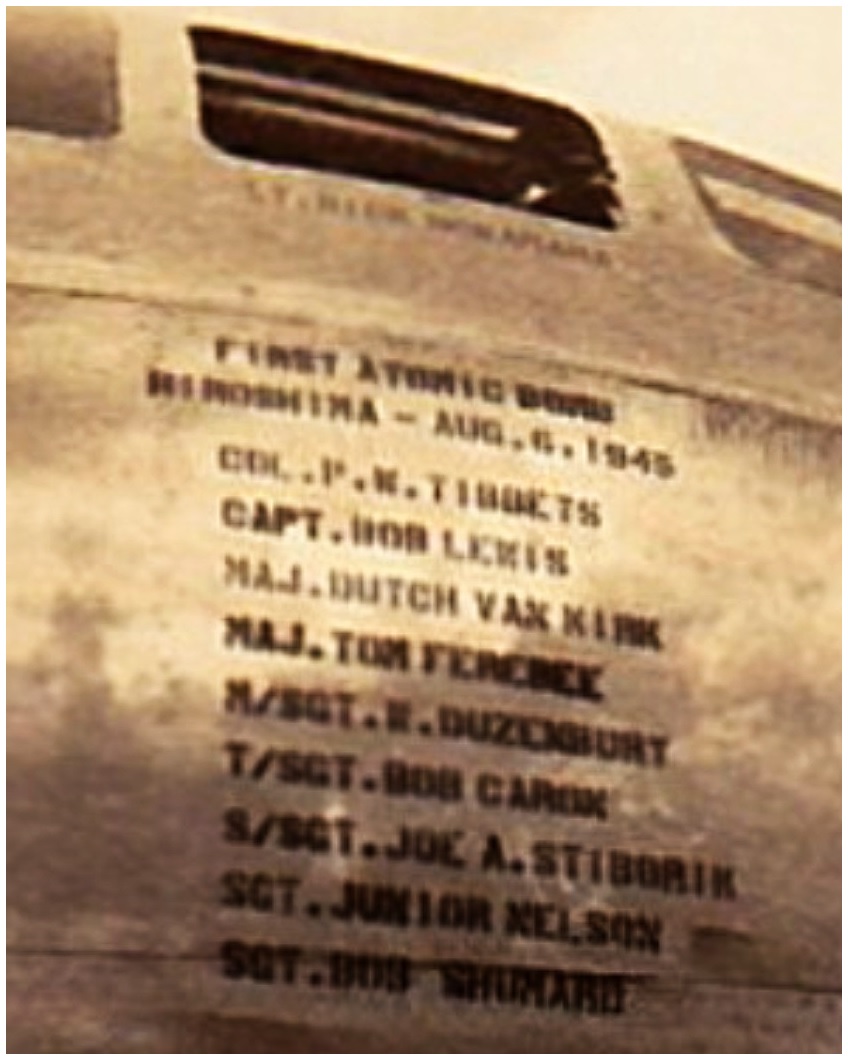

The only other photos showing the starboard side of the ship must have been taken almost immediately after the plane landed. The source of one photo is not identified. It must have been an interim photo just after the mission was completed. The photo contains the phrase: “First Atomic Bomb – Hiroshima – August 6, 1945” in standard military identification stencil type font above a list of the crew members. Shortly thereafter, this phrase and the crew list were removed and replaced with the large script version of the phrase, probably for Army publicity uses.

“First Atomic Bomb – Hiroshima – August 6, 1945”

Interim Version of Enola Gay Identification Lettering

This Version Was Erased and Replaced by the Large Script Version. The color and light conditions suggest the photo was taken at the same time of the cursive inscription was made; and both were made after the plane landed at Tinian and were greeted by General Spaatz and ground crew (the starboard nose is clean in the photo above of that gathering).

Source: Wingman1, source unknown.

“First Atomic Bomb – Hiroshima – August 6, 1945”

“First Atomic Bomb – Hiroshima – August 6, 1945”

Closeup blown up from previous photo

The same script message as seen in my father’s photo were taken by Frank J. Davis and his photos are archived in the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University. One of his three photos is shown below.

“First Atomic Bomb – Hiroshima – August 6, 1945”

(Photo by Frank J, Davis – SMU Collection)

I would surmise that the erasure of the previous stencil version and its replacement by the script version was carried out with the full approval of senior commanders at the 509th headquarters after the Nagasaki bombing or maybe at the direction of Colonel Tibbets as he had directed the name Enola Gay to be painted on his plane just before the mission commenced. An artist could be easily recruited on the Tinian airbase as many planes carried colorful images and scripting and many large conventional bombs carried script messages.

From discussions with my father, it seems that the script message encapsulated the end point of the war for thousands of American airmen that had been operating around the clock firebombing Japanese cities. Although some airmen may have enjoyed getting revenge on the Japanese for killing their comrades, the overwhelming majority of soldiers and airman were just tired of war and wanted it to end by any means possible, especially after the surrender of the German Third Reich in May, 1945. Unlike contemporary wars where military personnel are rotated out of the front lines after a year or so of duty, during World War II, once you were in the war, you were in it until the end and victory was definitive. War exhaustion may have numbed American troops to the point that mass death was an everyday occurrence. Even though Japanese soldiers usually fought to their death, the American forces were just as determined to keep killing the Japanese soldiers whatever the casualties to themselves until the Imperial Japanese Army no longer existed as a viable fighting force. Even though every American soldier abhorred the idea of fighting many more bloodbaths on the Japanese home islands, they were resigned to the human cost that unconditional surrender would require.

The Battle of Saipan started on June 15, 1944 and lasted almost a month. American casualties reached nearly 14,000 with over 3,400 dead. The Japanese Garrison of 29,000 defenders was virtually wiped out except for a few hundred soldiers captured. Out of 25,000 civilians living on the island before the battle started, only a few thousand survived. When my father arrived on Saipan, civilians were still jumping off the cliffs.

The spring of 1945 was a series of seemingly unending bloodbaths with terrible casualties for both Japanese and American fighters. In the Battle for Iwo Jima, American naval forces bombarded the tiny island for months before the 70,000 marines invaded on February 19, 1945. 7,000 Marines were killed and another 20,000 were wounded. For the Japanese, the entire garrison of 20,000 defenders, mostly draftees, was wiped out, except for a few hundred captured soldiers.

Only a month and a half later, the Battle for Okinawa commenced a three-month struggle. On April 1st, 60,000 Marine and Army soldiers invaded. Five days later, a wave of 355 kamikaze suicide planes rained down of American forces. For many of the Japanese pilots, these flights may have been their first and last combat mission. The kamikaze attacks from 2,000 aircraft lasted until June. Victory for the Americans cost 49,000 casualties with almost 12,000 killed. Again, the Japanese garrison of 90,000 defenders was entirely wiped out with only a few survivors. Most tragically, Okinawan civilians suffered approximately 150,000 deaths.

At the same time, General Curtis LeMay’s air war campaign against Japan, mostly based on Saipan and Tinian, bombed and burned 59 major Japanese cities with massive casualties especially due to fire. When it came time to attack Japan with the revolutionary atomic bomb, there was no reluctance in the American military and political command. And, even though ground crews on Saipan and Tinian did not know the specifics of the top-secret new weapon, they knew something was up because of the high security surrounding a special group of “Silverplate” B-29 Stratofortresses parked in a special compound.

After a 12 hour round trip flight with almost no glitches, “Little Boy” dropped out of the Enola Gay and, in a micro-second, ended the essence of the city of Hiroshima in one blinding blast and a resulting firestorm. More civilians died in the fire bombing raids on Tokyo or in the Battle of Okinawa, but those deaths took days and weeks to add up. With Hiroshima only one shot was fired and there was no defense. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the origins of “Shock and Awe” warfare. The tactical goal for the Americans was to knock an important naval supply port out of the war, which could have been easily accomplished with a conventional fire-bombing raid, but the real strategic goal was to spread shock of unimaginable proportions, especially to the supreme Japanese military commanders.

The prospect of real atomic warfare in Japan during the 1940’s and potential atomic warfare in Korea during the 1960’s brought the lives of my father and myself together historically, but we came away from the experience with completely different conclusions. He was very proud of his service in helping to carry out a small part in the atomic bombing missions over Japan that ended the war. On the other hand, I am still troubled by the thought that I came so close to such a momentous decision as personally detonating an atomic bomb in a densely populated metropolis on so little historical knowledge and justification. That concern has sent me on a lifetime of learning history and trying to create a more just and equitable world.

FURTHER READING FROM THE EDITOR

“From a Military Theater…to Theater of the Absurd,” in P. Hayes, Pacific Powderkeg, American Nuclear Dilemmas in Korea, Lexington, 1990, pp. 49-51, here

“Case 2: Atomic Demolition Mine Combat Engineer, 1968 Korea,” part 2, Anthony J. Colangelo & Peter Hayes, “An International Tribunal for the Use of Nuclear Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, pp. 240-243, posted on line, June 11, 2019, here

“Public Relations, chapter VII, p.75, History of the 509th Composite Group 313th Bombardment Wind Twentieth Air Force Activation to 15 August 1945, August 31, 1945, here

P. Hayes, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki: There were other choices“, Global Asia, 10:2, Fall, 2015, pp. 62-66, here and E. Colby, “Ultimately Japan Brought the Bomb on Itself,” Global Asia, 10:2, Fall, 2015, pp. 56-61, here

III. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent