NAPSNet Special Report

by Peter Hayes and Roger Cavazos

9 March 2015

I. SUMMARY

In 2014, North Korea neither overcame its isolation due to its nuclear weapons and hostile geostrategic posture, nor reformed its economy. Kim Jong Un learned on the job, consolidated his leadership, avoided military risk, and opened new channels to South Korea, Japan, and Russia to reduce dependence on China.

Peter Hayes is Co-founder and Executive Director of Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability; Honorary Professor at the Center for International Security Studies, Sydney University, Australia. Roger Cavazos is a retired US military officer and Nautilus Associate.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

Acknowledgement: This essay is the long version of the overview of North Korea in 2014 in Asian Survey, 55:1, January-February 2015, pp. 119-131, also available here.

I. REPORT BY PETER HAYES AND ROGER CAVAZOS

North Korea in 2014: A Fresh Leap Forward Into Thin Air?

Introduction

Kim Jong Un declared on January 1, 2014 that the DPRK should make “a fresh leap forward on all fronts of building a thriving country filled with confidence in victory!” [1] Kim Jong Un’s official ascension to power began when official mourning for his father Kim Jong Il ended on 17 December 2014. Of the three regents bestowed upon him in 2011, none are left; of the eight who escorted his father’s hearse, only three are still in their positions: Kim Jong Un, Kim Ki Nam and Choe Thae Bok.[2] In spite of this turmoil at the top, the North Korean state remained stable, even when Kim Jong Un disappeared from public view for over a month. In the first quarter, North Korea was expected to ramp up to another cycle of nuclear or missile testing in the last quarter of the year. In fact, it engaged in a diplomatic offensive at the United Nations, and in the European Union, Southeast Asia, South Korea, Russia and Japan. North Korea conducted family exchanges for the first time since 2010, held high-level military talks with the South for the first time since 2007 and sent a delegation of unprecedented rank to South Korea. North Korea announced several new Special Economic Zones, promulgated more laws governing those zones, but has not invested in the energy infrastructure required to make them successful. Moreover, no-one of sufficiently high Party rank has been appointed to run the Zones to overcome the many barriers to their success. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the economy grew at a very modest rate for the fourth consecutive year, with gains in key export sectors trading with China in resources and textiles[3], but the North remains trapped in a low level equilibrium – or conditions of subsistence level wages, scarcity of arable land and inefficient production methods – largely of its own making, but now beset by the financial and trading effects of international and unilateral sanctions.[4] It reportedly avoided wide-spread famine in 2014 due largely to fewer crops being diverted to feed the declining number of livestock.[5] It may even become self-sufficient in cereals – but only in that category.[6] Although it did not test a long range rocket, it did test more and a greater variety of short and medium-range missiles tests than ever before.[7] Overall, therefore, there is no evidence of a fresh leap on any front, political, economic, ideological, cultural, military or external-diplomatic—but nor is there evidence of instability in the regime. Kim is devoting considerable energy to reducing the DPRK’s overwhelming dependence on China, opening new external relationships with Japan and Russia, and deflecting an international campaign to indict him for crimes against humanity due to the DPRK’s human rights transgressions.

This behavior is consistent with Kim learning on the job, exercising great caution, and being satisfied with minor incremental but stabilizing internal changes while avoiding sudden, shocking changes to the DPRK’s political and economic systems. Kim may also be biding his time to formulate a new strategy for 2015 and beyond now that the official mourning period for his father is complete.

Domestic Political Front

In 2014, Kim Jong Un and North Korea recovered from a remarkable and in the DPRK, rare event, the public trial and subsequent execution of Jang Song Taek, one of the most senior figures in the regime. Because of North Korea’s policy of guilt by association, anyone within three degrees of separation from the guilty party may also be sentenced for the crime committed by one person. In addition to Jang, reportedly his brothers and their families were executed. [8] An unknown number were exiled and likely a much larger number subjected to “re-education.” Also, in December 2013, Jang Song Taek’s wife, Kim Kyong Hui – she was Kim Jong Il’s sister and reportedly key advisor, suddenly disappeared and did not reappear in 2014. However, not all of Jang’s associates were removed.

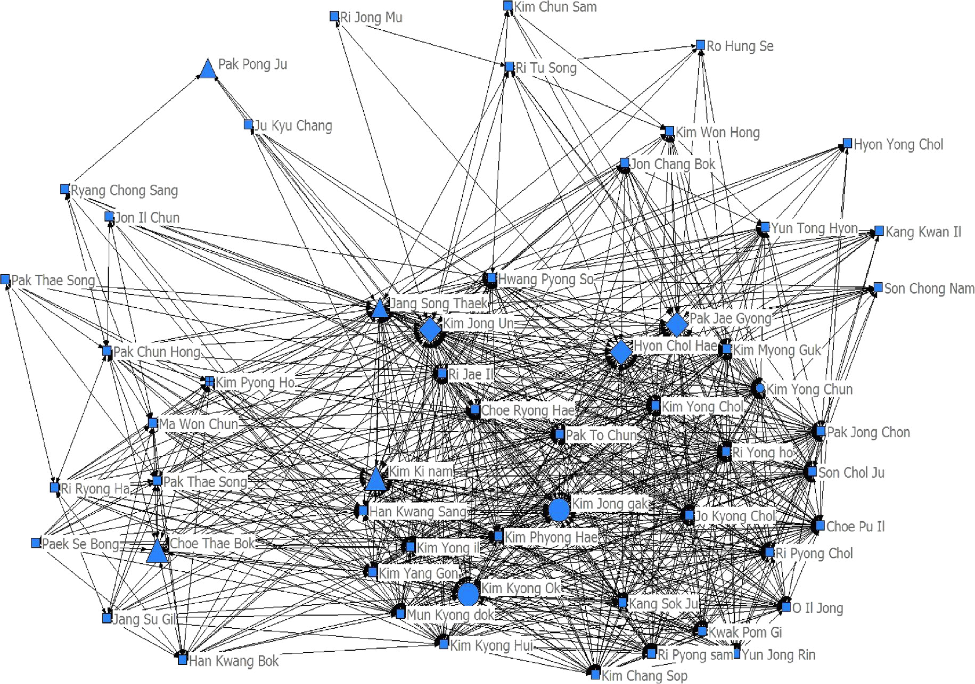

There was considerable speculation that Kim Jong Un’s grip on power was diluted in 2014. Detailed analysis of people and their postings shows that it is likely that Kim is revitalizing old institutions and making frequent personnel changes—the classic way that the ruling family has broken up potential alignments of opposition over the decades.[9] Some observers (especially those associated with defector groups), suggest that the long-standing political control mechanism, the Organizational Guidance Department (OGD) of the Korean Worker’s Party, exercises more power than in the past, and that Kim Jong Un exercises less absolute and personal power than past North Korean leaders.[10] Kim Jong Un’s disappearance for 40 days in September and October fueled this speculation. However, the OGD has long been a key control mechanism, and there is insufficient evidence from studies of decision-making style, on-the-spot guidance appearances, or personnel changes to support (or refute) this hypothesis.[11]

Figure 1: Leadership Network under Kim Jong Un, January 2012 – October 2012 2009eDecember 2011 Circles = Conservatives; Triangles = Moderates; Diamonds = Neutral. Ishiyama, J., Assessing the leadership transition in North Korea: Using network analysis of field inspections, 1997e2012, Communist and Post-Communist Studies (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2014.04.003

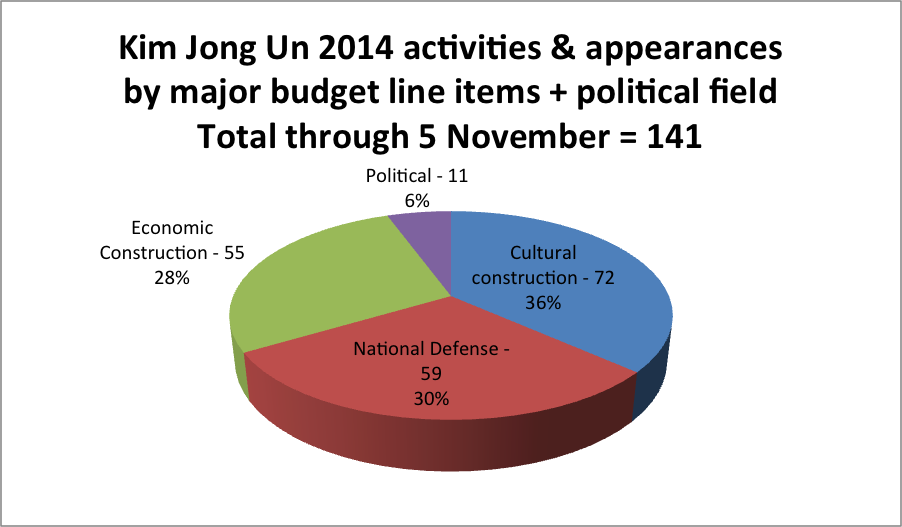

Figure 2: Hayes & Cavazos, Kim’s appearances in 2014, forthcoming

Some (especially in the United States) also argue that the North embarked on the final stage of intra-leadership conflict that will lead to the unravelling and collapse not only of the Kim clique, but the regime as a whole.[12] However, we only see limited evidence to that effect in the aftermath of the Jang purge. Instead, Kim Jong Un appears to have further consolidated his power, and the North made a number of strategic moves more consistent with a single supreme leader exercising power than a collective group running the regime. In particular, sending General Hwang Pyong So, North Korea’s most senior military figure and number two in the command hierarchy, to Seoul for the Asiad games on October 4, 2014 is more consistent with the view that Kim is able to make highly significant political decisions very quickly than could a collective decision-making process. It also suggested that Kim was confident in his hold on power.[13]

Although North Korea is the antithesis of a democratic polity, it does hold country-wide elections every five years. On March 9th, Kim Jong Un was elected to the 13th Supreme People’s Assembly. It was his first election after becoming suryong or the “brain” leader of the DPRK’s peculiar formulation whereby the party and masses are integrated via the person of the leader. North Koreans elected their parliamentary representatives with a voting rate of 99.97 percent of registered voters, consistent with previous voting rates.[14] The main function of the elected assembly is to legitimate the regime’s decision in a formal ritual of acquiescence and obeisance to Kim’s rule in the aftermath of the extraordinary purge of Jang which revealed publicly that the rot had reached the core and the top ranks of the regime. New candidates to the SPA made up about 45percent of members.[15]

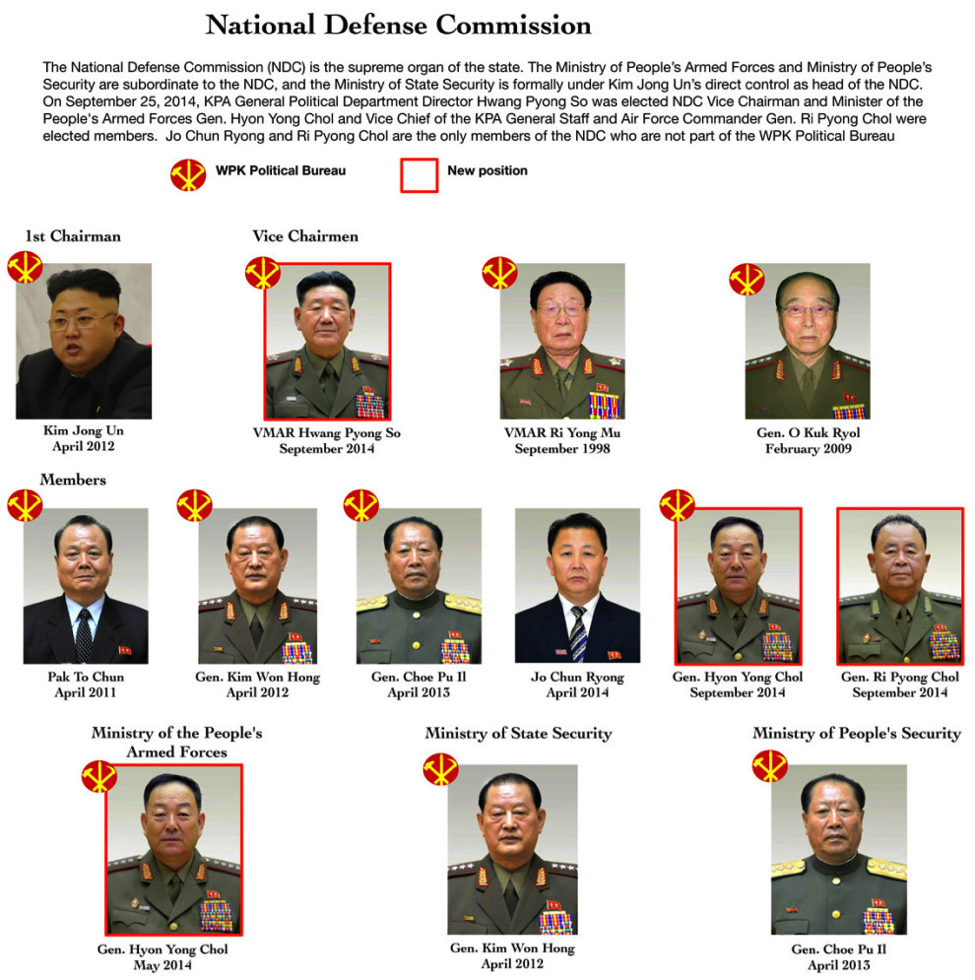

Figure 3: North Korea National Defense Commission, 38North

http://38north.org/2014/10/mmadden100614/14-1006-ndc_september2014_med/

That rate is slightly lower than but still consistent with past rates of around 50 percent turnover and consistent with Kim making steady, incremental changes ; not indicative of an across the board purge. Thus, in 2014 Kim churned top-level military leadership by removing, replacing or installing 60 percent of the people in the 10 person supreme organ of national power, the National Defense Commission. His actions are consistent with weakening the institution and placing his form of civilian control over the military: he fired one Minister of Defense (after the previous one was in position for mere months), he removed two Vice Chairs of the National Defense Commission and nominated new people to those positions and added two members of the National Defense Commission[16] which has the effect of diluting the individual power of each person on the committee.

Economic Front

North Korea’s economy was basically static in 2014. North Korea continued an internal policy of assigning Vice Premiers (one level above Minister) to the three portfolios most closely associated with a centrally planned economy: State Planning; Chemical Industry and Agriculture.[17] In spite of ambitious goals—to pursue economic revitalization and a nuclear weapons strategy at the same time in a military-dominated economy, the so called byungjin nosun line ,平行发展, 병진노선 line announced by Kim in March 2013—the DPRK did not create new economic institutions or repurpose existing ones to support this signature policy.

Doing so is difficult given North Korea’s rigid economic structure with its long-standing three economies:[18] the military economy, the line agencies (or state economy), the palace (sometimes referred to as the party) economy, and the more recent fourth economy suffering from fitful stops and starts of permission followed by appropriation, the private, mostly informal and small-scale market economy called jangmadang, 市场, 장마당(literally marketplace).[19]

The sole apparent exception was the establishment of Special Economic Zones in 2013 with another tranche of designations in 2014[20], but there is no evidence in 2014 of substantial commitment to these Zones in terms of infrastructural investment, provision of energy, or appointment of senior party leaders to overcome the many obstacles to the zones success.

Figure 4: North Korea’s list of Special Economic Zones as of December 2013 http://ajw.asahi.com/article/asia/korean_peninsula/AJ201310280106

The zone thought to be most likely to develop quickly into a success story was the joint zone under construction with China on the North Korean island of Hwanggumpyong (黄金坪岛 /황금평) at the mouth of the Yalu River near Sinuiju which would have provided North Korea with access to approximately 110 million consumers in China’s Northeast, but this zone appears to be languishing. China finally confirmed the obvious on the 30th of October that the opening for a new bridge across the Yalu river to North Korea is indefinitely postponed.[21]

Figure 5: North Korea end of bridge to nowhere (right) is in the middle of a field and shows lack of road network. China’s end (left) shows rich road, rail, water connections.

China invested $324 million dollar to build a bridge and associated road and railways on the Chinese side. North Korea then asked China for a loan to build their part of the bridge which mainly consists of roads from the bridge landing and customs houses. In contrast, the inter-Korean Kaesong Industrial Region north of the Demilitarized Zone has been a relative bright spot despite extreme turbulence between the two Koreas. After being shutdown altogether by the DPRK in September 2013 over a political spat, it has returned to normal operations in 2014[22]

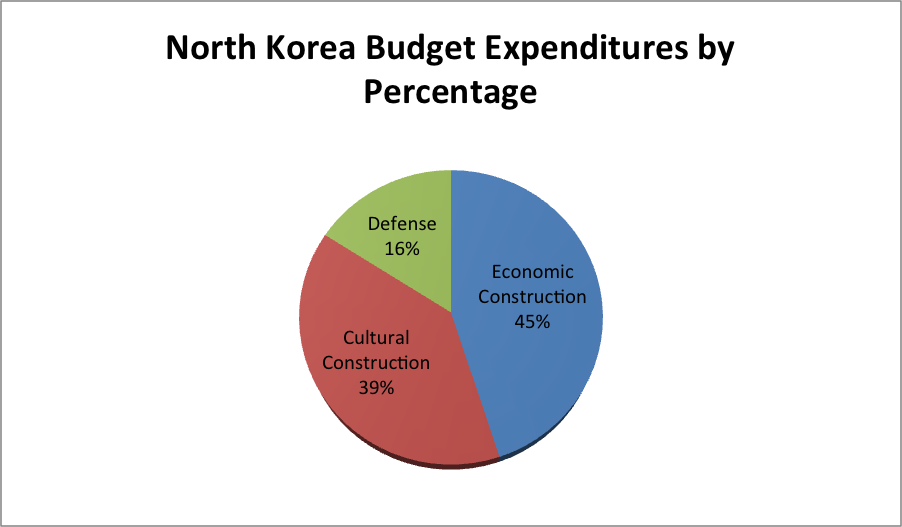

Overall, the budget was as much based on political-ideological as it was on practical investment logic, which is business-as-usual in the DPRK.[23] Thus, North Korea’s official figures show it spending 45 percent of its state budget on “economic construction.” North Korea tailors their definition of “cultural construction” to include activities like education, healthcare, sports, music and arts. In GDP terms, North Korea ranked this priority more than twice as important as defense by dedicating 39 percent to “cultural construction”. Defense expenditure received only 16 percent of the budget – a one percent increase from the previous year. Kim’s “on-the-spot” guidance suggests his main focus is on defense and economy linkages, light industry and sports[24] but whether this is supported in practical ways by credit, tax and fiscal policy, or simply shows his exhortatory intent is unknown – even in Korean-language press.

Figure 6: North Korea’s planned expenditures in 2014 by major budget line items as provided by North Korea.

The four economies are linked in various ways both legal and otherwise. In the past, loyalty to suryong (a corporatist concept in North Korea for the national leader) and his family was the primary criterion for receiving rewards such as access to jobs or opportunities in any of the three economies where one could earn hard currency. Today, there are several anecdotal example of growing rich by working in the fourth market or by extracting private rent by exploiting opportunities presented by the operations of the dominant three sectors, partly in response to imperatives to do so arising from the collapse of the official public distribution system, from the requirement for organizations to self-finance, and from simple greed when faced by opportunity for lucrative corruption. How Kim will manage the emergence of real pools of accumulated wealth, even if they are politically compliant, remains to be seen.[25] The regime does not hesitate to shut down growth areas when it judges it expedient, as it did in October 2014 until 2 March 2015- closing its borders to tourism, one of the few growth sectors of the service economy, in response to the Ebola threat.[26],[27] Only selected traders and visitors have been allowed to cross the border in or out and even high ranking North Koreans to include North Korea’s nominal head of state, President Kim Yong Nam are quarantined for 21 days upon return to North Korea.[28] A detailed list of who was allowed in and out would reveal North Korea’s priorities but nonesuch is publicly available. So long as the general population have enough to subsist and shelter with sufficient heat to survive, and enough fuel for the military to operate and for food to be grown, harvested, processed, distributed and cooked, then it appears the regime will remain poor but stable.

North Korea’s generally poor public health system[29]is a drag on the economy directly (loss of labor and productivity in a labor-short economy) and indirectly (by creating a vulnerable population that induces the regime to shut down all border crossings with resulting immense costs including disruption of tourist traffic, now an estimated 20,000 per year). The DPRK working population suffers from enduring and irreversible effects of malnutrition and stunting from prior famines, communicable diseases like hepatitis B and sexually-transmitted infections, drug-resistant tuberculosis and viral infections like dysentery due to collapsed urban sewage treatment plants infecting drinking water that occur in North Korea at rates approaching sub-Saharan Africa.[30] Most North Korean households use coal-fired ondol (온돌)heating and cooking with associated high rates of carbon monoxide poisoning.[31] North Korea is also experiencing: a return of malaria,[32] possibly driven by climate change warming, and from outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease.[33]

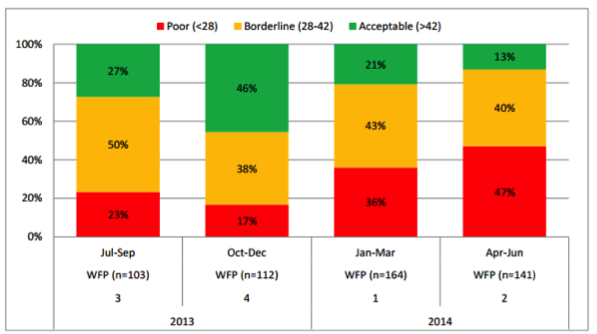

Figure 7: Percentage of households with Acceptable, Borderline or Poor Food Consumption. World Food Programme, “Protracted Relief and Recovery Operation (PRRO) 200532 ‘Nutrition Support for Children and Women’ in DPR Korea” 2014, at: http://www.wfp.org/sites/default/files/PRRO%20200532%20M&E%20Bulletin%202014_2nd%20quarter.pdf

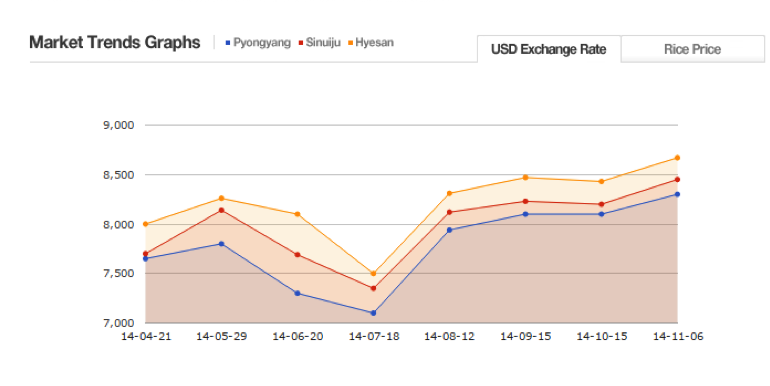

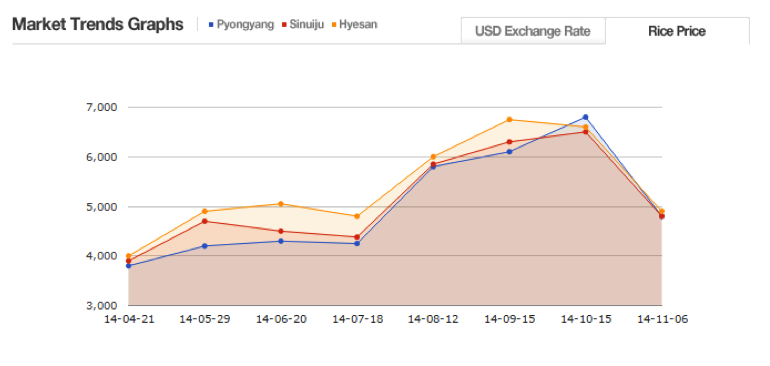

In 2014, North Korea’s inflation rate remained stubbornly high as it has been since a botched currency reform attempt five years earlier. When combined with rampant corruption, individuals and economically significant organizations have a strong incentive to use and hold foreign currencies, especially now that the DPRK won is convertible (the 5,000 won note dropped Kim Il Sung’s picture[34]). The Chinese yuan is the most easily accessible foreign currency, but the dollar is preferred according to many North Koreans with the Euro also being used. The dollar will likely end the year at about the same exchange rate, but the endpoints mask a roughly 12 percent drop of the dollar in March, a resurgent dollar, and then another roughly 12 percent drop followed by another resurgence.[35] Meanwhile, the price of rice in three North Korean cities (Pyongyang, Hyesan, and Sinuiju) generally climbed throughout the year.[36],[37] Normally, the dollar drops at least once and rises at least once during the lean period when North Koreans need to buy foodstuffs. It is still not clear whether there was a correlation between North Korea’s border being closed for Ebola and the price of rice in North Korea.

Figure 8: USD-KPW (North Korean Won) exchange rate via DailyNK; http://www.dailynk.com/english/market.php?page=2&cataId=

Figure 9: Price of rice in selected cities via DailyNK;

http://www.dailynk.com/english/market.php?page=2&cataId=#

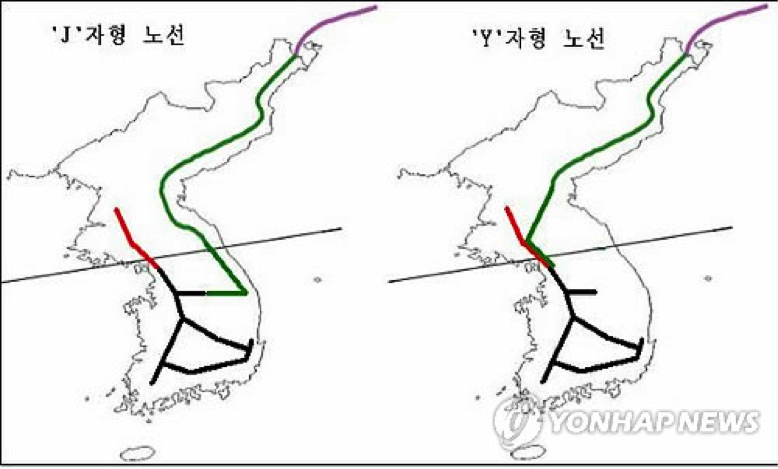

One key infrastructural choice reveals Kim’s desire to reduce the DPRK’s overwhelming economic dependency on China that accelerated after 2008.[38] This was its appointment of a Russian firm to revamp North Korea’s rail and road system at a cost of about $25 billion in exchange for access to North Korea’s vast mineral resources.[39] This deal was likely linked to Russia’s decision to forgive 90 percent of the DPRK’s Cold War debt of $11 billion and to use the remaining debt to fund health, education, and energy rehabilitation. The deal may also pave the way for a Russian gas pipeline to transit the DPRK en route to the ROK.[40]

Figure 10: Possible pipeline configurations from Russia through the Korean peninsula.

http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/politics/2011/09/27/0505000000AKR20110927076000014.HTML

However, the main constraint on all these plans remains North Korea’s energy infrastructure.[41] The power grid is a shambles and generally incapable of consistently meeting demand where it does exist. In many places it simply doesn’t exist and neatly explains North Korea’s suppressed demand expressed in the import of large numbers of small diesel generators, and rapid diffusion of small photovoltaic (PV) cells combined with car batteries.[42] The combinations of generators and PV cells offer very high cost electrical energy, but also reveal the even higher opportunity cost of not having available power.

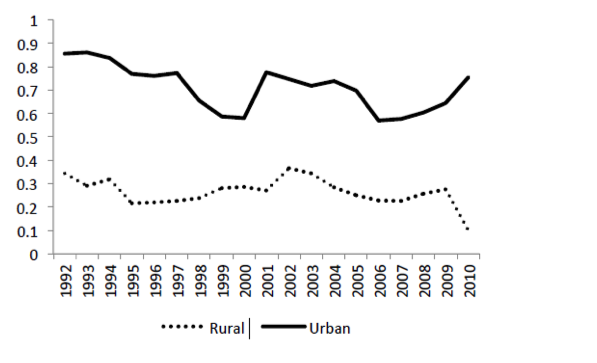

Figure 11: http://eltonzeng.blog.hexun.com/84496457_d.html

The rehabilitation of the power system is a 100 billion dollar plus project (roughly two and half years of North Korea’s GDP) over at least a decade (the transmission and distribution system alone is an estimated 40 billion dollar cost or about one year of GDP). Projects on this scale must languish given the parlous state of the economy and uncertainty about the future industrial geography of the DPRK given the gravitational pull of the South Korean, Chinese, and Russian economies. Sanctions against North Korea by the United States and its allies have long constrained the North Korean economy, but it is now possible to quantify the impact of sanctions on the lives of ordinary North Koreans by using shifts in relative night-time luminosity over time in different geographic areas of the DPRK. Empirical studies show that the big cities have been protected and the impact of sanctions has been shifted on to rural and deprived areas in the DPRK.[43]

Figure 12: Urban and rural luminosity using the adjusted data: North Korea pg 26

Yong Suk Lee, https://web.stanford.edu/~yongslee/NKSanctions.pdf

Figure 13: Luminosity as a surrogate for economic prosperity: China, South Korea and North Korea

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=83182

Military Front

2014 was a year of relative calm for the DPRK’s military. Other than a few firefights on the disputed western seas, and a few shootouts along the Demilitarized Zone (some to shoot down pamphlet balloons launched from South Korea), the Peninsula was not at a high state of military alert for most of the year, even during the large-scale US-ROK exercises Key Resolve (command post exercise 24 February – 3 March ,Foal Eagle (field exercise 3 March – 18 April) and Ulchi Freedom Guardian (computer exercise 18 – 29 August).[44],[45] North Korea denounced these exercises as prefiguring American nuclear attack, but otherwise did little provocative this time in military terms.

Many observers anticipated that it would be a hot year in terms of nuclear and missile testing, however. This was due to North Korean demands that the United States return to the Six Party Talks or bilateral dialogue without preconditions. The North let it be known via China in April 2014 that if it did not get a positive response, it would escalate to a nuclear or long-range missile test in late 2014. However, this did not occur and instead, the DPRK launched a political-diplomatic offensive in August to put pressure on Washington (and Beijing) to agree to its demands for talks.

Thus, there was no military fresh leap forward in 2014. Like the economy, North Korea’s conventional military capabilities were static to slightly declining in 2014. Meanwhile, ROK, US, and Chinese forces are growing and modernizing, increasing the relative inferiority of DPRK conventional forces throughout the year.

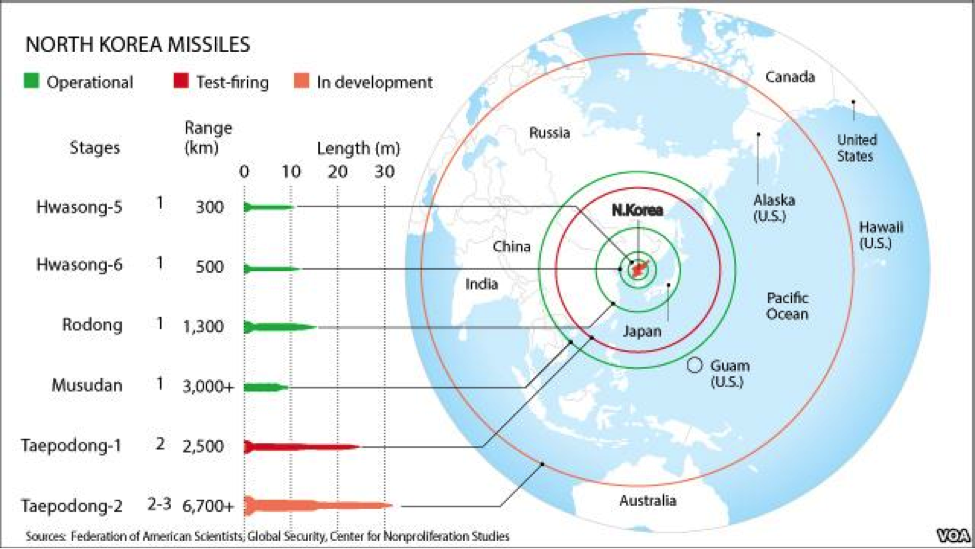

In 2014, North Korea invested in conventional forces in incremental gains in that might exploit US and South Korean military weaknesses. These included longer-range multiple rocket launchers aimed at northern Seoul or military staging areas south of the Demilitarized Zone, as well as deploying a new mix of domestic and previously owned Soviet era and Chinese submarines. The submarines are likely to be used in a defensive mode to attack surface vessels approaching the DPRK’s coastline in wartime. The most notable examples of newly acquired (or at least new to North Korea) missiles such as the KN10, KN02 and KN08 road mobile Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM).[46],[47],[48], [49]

The KN10 with a range of 200-300 kilometers means North Korea can strike far south on the Korean peninsula including the locations where US forces would come onto the peninsula to reinforce South Korea’s military. Alternatively, the KN10 allows North Korea to strike the military headquarters that would command any Chinese forces that might move into North Korea.

The KN02 is an anti-ship missile likely acquired to keep the US Navy far out at sea which means US Navy aircraft have less time over North Korea and are able to fly fewer sorties per day.

The KN08 road mobile ICBM is meant as the ultimate (last line) missile threats since they are extremely hard to find and provide North Korea with one more viable military means to threaten or terrorize South Korea, US forces on the peninsula and China. The combination of the three are a type of porcupine strategy to raise the cost of invasion and increase the incentive to enter into talks, but none of them can win a military contest and none of them can sustain a military offensive. Most of these additions were useful only for launching limited or localized tactical offensives, and cannot sustain a major strategic offensive. Quite the opposite, all three are a-strategic after use.

Figure 14: Estimated North Korea Missile range rings http://armscontrolcenter.org/publications/factsheets/fact_sheet_north_korea_nuclear_and_missile_programs/

The majority of North Korea’s military commanders are officers who spent most of their life in civilian roles. Kim Jong Un has rapidly changed senior posts and appointed leaders with personnel connection to him and demonstrated party loyalty. The senior ranks of the North’s military have almost no wartime experience in their entire career since the guns fell silent sixty one years ago along the Demilitarized Zone. They have made some fresh leaps in tactics such as exercising amphibious assaults or offensive cyber warfare, but overall, the Korean People’s Army is a conservative conventional military force mobilized with a partisan-guerilla political ideology. Apart from an all-out sledgehammer attack on Seoul with artillery and rocket-fire that would last only a few days before it would be suppressed by US and ROK forces, North Korea’s military can be confident in achieving only one mission today: occupying its own country to enforce loyalty to the regime, thereby keeping large numbers of young men and women occupied by laboring in mass mobilizations such as monumental construction and infrastructure, transport, and agricultural projects.

As a conventional force, the Korean People’s Army was likely unimpressed by the notion that it should subordinate itself to nuclear weapons that would draw fire, divert valuable resources, and (if successful in deterrence terms), never be used, and may now be used to substitute for conventional forces. Nonetheless, the KPA is now charged with deploying whatever nuclear weapons the DPRK has produced.

They must also quickly develop a roadmap for a North Korean nuclear operational force if there is no serious effort from the West to slow down the development. However, the laws of physics that determine how nuclear weapons and delivery systems perform are the same in North Korea as anywhere else, in spite of North Korean voluntarist thinking and improvised practice found in all domains of North Korean life. Conversely, North Korean ideology will inflect how they shape strategic options and deploy their force within these physical parameters, possibly in ways alien to western strategic thinking. Finally, North Korea has stated its intentions and demonstrated its capabilities in observable ways, providing a limited but substantial empirical basis for analyzing and interpreting this threat which will only continue to grow.[50]

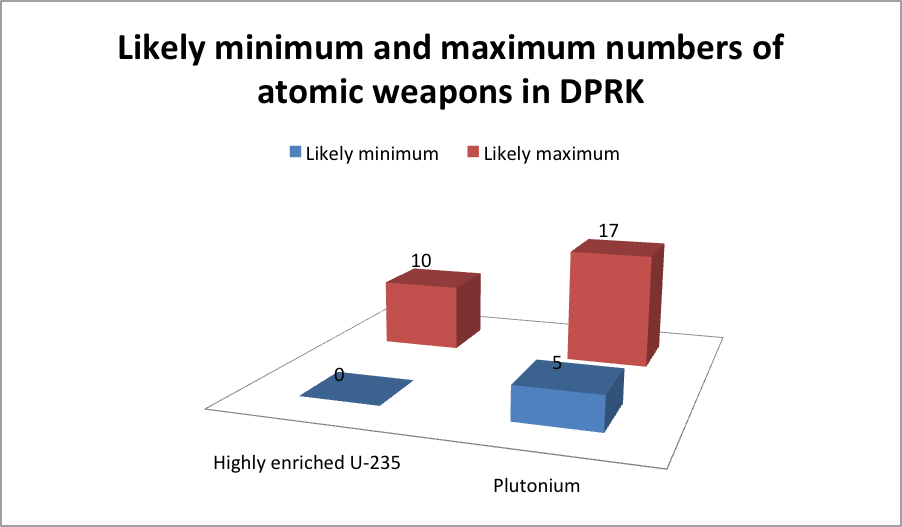

Figure 15 Likely minimum and maximum numbers of atomic weapons DPRK has on hand by type.

Data from David Albright and Christina Walrond. http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/dprk_fissile_material_production_16Aug2012.pdf

By 2014, the DPRK’s stockpile may be as small as five weapons (five Plutonium and zero Highly Enriched Uranimum (HEU)); or it may be as large as 27 (17 Plutonium plus ten HEU). .[51] The exact figure depends on the number of enrichment centrifuges in operation, the enrichment plant operating factor, whether low-enriched fuel is made for the DPRK’s small LWR in the 2012-2014 period, and the level of enrichment used in DPRK enriched uranium warheads. Similar uncertainty exists for plutonium stockpiles for burn-up of uranium fuel, reprocessing efficiency of plutonium separation from spent fuel, and amount of plutonium used in North Korean warhead designs. To what extent this fissile material has been weaponized, that is, not just tested in crude nuclear devices, but developed into a deliverable weapon for detonation on a military target, is unknown and in North Korea that knowledge will likely be limited to only a few people.

Since no one is quite sure how many nuclear weapons North Korea currently possesses, no one is certain how many they will have if nothing is done to address the growth. However, the range of “minimal growth, minimal modernization”, “moderate growth, moderate improvement” and the very scary “rapid growth, rapid improvement” scenarios indicate that North Korea’s nuclear arsenal can grow at different rates.[52]

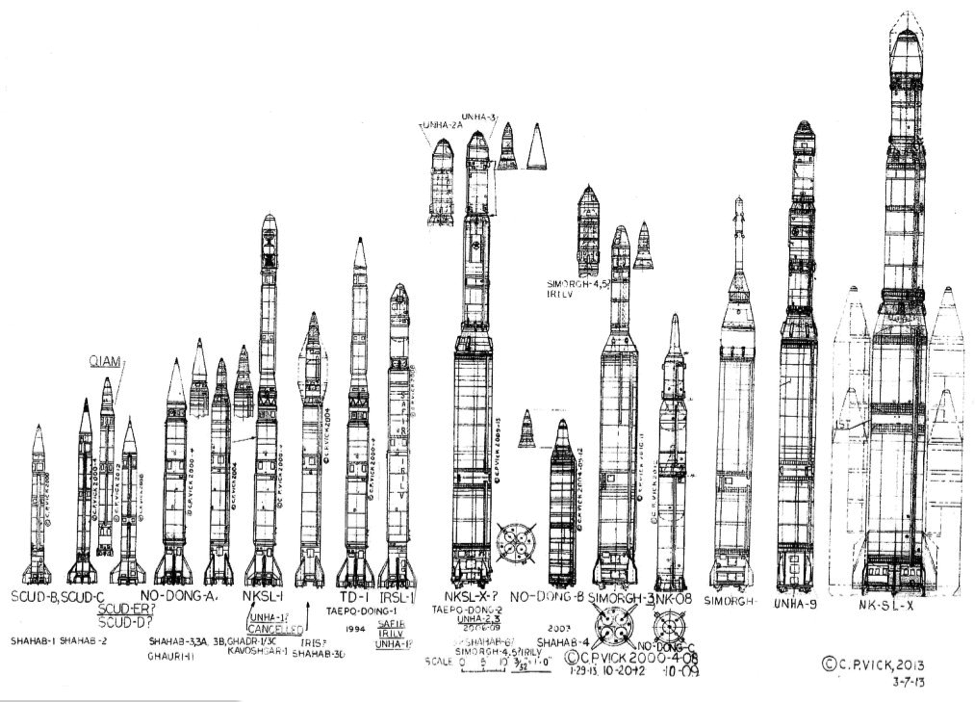

Even if the fissile material is weaponized, delivering these weapons is another matter altogether. North Korea has proven short- and medium -range nuclear delivery capability, including bombers, fighters, and missiles, once it has made nuclear weapons small enough to fit on these different types of delivery platforms. There is little agreement outside of North Korea, let alone definitive answers to indicate when they will be able to miniaturize nuclear capabilities. It currently possesses several types of missiles: Scud B (range 320 kilometer, payload 1,000 kilograms), Scud C (range 500 kilometer, payload 770 kilograms), Nodong (range 1,350-1,500 kilometer, payload 770-1,200 kilograms), and Musudan (range 3,000 km plus, payload 650kg). Many of these missiles are known to be of poor reliability and accuracy, but if the DPRK is firing nuclear weapons in an all-out attack on South Korean cities, this might not matter too much—although the plausibility of launching such a suicidal spasm by firing such an unreliable weapon system is dubious. The range of scenarios in which firing such a weapon would be rational is miniscule—perhaps in a last ditch effort to stave off attack and occupation in an all-out war.[53]

Figure 16: Global Security.org: Family of missiles resulting from Iran to DPRK tech transfer. http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/world/dprk/kn-08.htm

Although test-launchings of inter-continental ballistic missiles―Daepodong-1 (大浦洞 1号 / 대포동 1호) missile (range 1,500-2,500 kilometer, payload 1,000-1,500 kilograms) on August 31, 1998, Daepodong-II missile (大浦洞 2号 / 대포동 2호) (range 3,500-6,000 kilometer, payload 700-1,000 kilograms) on July 6, 2006, and similar ones on April 5, 2009 and on April 12, 2012―are all believed to have failed, the most December 12th, 2012 launching of space launch rocket Unha 3 (银河3号 / 은하3호)with a dual-use application to long range missiles was successful in launching a small satellite into orbit—although it was unable to communicate with or control the satellite due to its apparent tumbling.[54] Escaping earth’s surly bonds is only part of the chain required to credibly threaten using ICBM’s. DPRK still has to miniaturize whatever it wants to put on top so that it fits in the relatively small space of the nosecone, then it has to ruggedize the package to survive the launch, the temperature changes and the buffeting of re-entry. DPRK also has to ensure the nosecone can withstand re-entry temperatures significantly hotter than the re-entry temperatures of a medium range ballistic missile. And finally, North Korea has to master guiding the weapon to its intended target. There is some evidence North Korea is working on almost all those steps, but none that indicates it has succeeded in integrating them or testing them as a system. Thus, the DPRK has the potential technical capacity to build components of the nuclear delivery systems able to cause considerable damage to South Korea, possibly to Japan, and speculatively, even to the United States. In October 2014, the head of US Forces Korea General Scaparotti stated that while North Korea has the technology to make a small nuclear warhead and put it on a missile, he did not know if they had done so, and if they had, it would likely have low reliability: “We’ve not seen it tested at this point,” he stated. “Something that’s that complex, without it being tested, the probability of it being effective is pretty darn low.”[55]

Designing, developing, testing, and deploying nuclear weapons is one thing. Commanding them effectively is altogether another. Little is known publicly about North Korea’s nuclear command-and-control system over nuclear weapons that are assumed to belong to the DPRK’s Strategic Force (so-called since 2012 when Kim Jong Il referred to it as such rather than the previous name, the Missile Guidance Bureau). However, Kim faces an obvious dilemma in that the political imperative is to maintain assured personal and centralized command of these weapons at all times, which implies direct control; whereas reducing vulnerability of these weapons to pre-emptive or retaliatory attack implies a degree of distributed command authority and resulting potential for non-wartime loss of direct control. It is assumed that in wartime, Kim Jong Un will move to deep underground command bunkers in the vicinity of Pyongyang, and likely rotate between them. What technical means exist for reliable communications and to ensure that North Korea’s nuclear weapons are under his positive control at all times is unknown. This is even more critical given reports that North Korea is working on submarine launched ballistic missiles and would likely have to devolve release authority from Kim to a submarine commander to put these weapons to sea.[56] If Kim were to not pre-delegate use authority, then the submarine would have to expose itself at the surface to receive orders, greatly enhancing the risk of exposure to US and ROK anti-submarine forces. If only Kim can authorize releasing a nuclear weapon, then a submarine must expose some surface in order to receive explicit permission and any exposed surface greatly increases the chances of that submarine being sunk.

Inter-Korean Front

Inter-Korean relations is the only front on which the DPRK might be said to have taken a fresh leap forward in 2014 although it took most of the year to make the leap.

Inter-Korean relations in 2014 did not start smoothly. The DPRK denounced South Korean President Park Guen Hye’s “trustpolitik” speech in Dresden on March 28, 2014. In the following months, the DPRK not only rejected the speech and its underlying concepts about a reunification “bonanza,” but began to issue insulting and derogatory comment about President Park that did not accord with Kim’s own call in his New Year’s speech for the two Koreas to abandon mud-slinging.

In response to Park’s reunification broadside, North Korea reiterated its longstanding position that only reunification talks based on the Three Principles and the idea of “By Our Nation Itself” and in accordance with July 4th 1972 joint statement, June 15th 2000 Joint Declaration and October 4th 2007 Declaration are acceptable.[57] It later focused[58] on the June 15th 2000 Joint Declaration which agreed to promote reunification as an amalgam of the “South’s concept of a confederation and the North’s formula for a loose form of federation,”[59] and thereby underscoring that subsumption of the DPRK by the ROK as implied in Park’s Dresden formula was a losing proposition for Seoul. Given Seoul’s attempts to activate a “trust politik” based low-level inter-Korean engagement with the DPRK after formally launching her unification committee in August[60], the DPRK seems to have succeeded in negating the Dresden line, at least for now.

Nonetheless, the DPRK surprised South Korea in February by agreeing to and then actually conducting the first family reunions since 2010[61] (although it refused to resume these reunions in early March)[62]and holding the first high-level military talks at Panmunjom after a seven year gap. North Korea also tried to restart the Mount Kumgang tourism project, but the South balked due to the killing of a South Korean visitor at the site in 2008, North Korea’s failure to investigate the incident to South Korea’s satisfaction and the subsequent appropriation in 2011 of Hyundai’s multi-billion dollar investment in the project.[63],[64] Unlike in past years, the DPRK did not ask for food aid or fertilizer during the lean months of winter and spring planting season for reasons of DPRK’s own choosing that remain unclear and unstated.

As the year progressed, the DPRK began to respond to the ROK’s specific overtures with proposals of its own. In June, it agreed to participate in the Russian-South Korean priority project of completing the Eurasian railway via Khasan to Rajin and thence onto South Korea including a link to Pyongyang.[65] So far, the DPRK has spurned calls for a biodiversity-oriented “peace park” in the Demilitarized Zone, but accepted South Korean humanitarian aid, primarily in the form of medication for tuberculosis control. It turned down ROK offers to provide assistance in suppressing an outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease in livestock (pigs) which continues to spread due to shortages of vaccine and means of diagnosis and disinfection.

(I can only find old pictures depicting present rail structure)Sending General Hwang Pyong So to Seoul for the Asiad games on October 4, 2014 with no advance warning was a bold move designed to overcome South Korea’s evident reluctance to move forward at the pace and depth desired by Pyongyang and to pressure the White House to resume dialogue. This unprecedented high-level three person delegation embodied the Vice Chair of the National Defense Commission (North Korea’s Supreme Organ of National Power – akin to the Politburo Standing Committee), the Workers Party of Korea, the Korean People’s Army, the Sports Committee, and the General Political Bureau. In short, they represented the triune powers of the Party, the military and the State.

Hwang met with South Korea’s National Security Director and the Minister of Unification – all of the officials on both sides plausibly have purview of substantively changing the relationship between the Koreas and yet very little followed directly from the meetings. North Korea postponed follow on talks after what it considered hostile exchanges.

Figure 17: Surprise visit by NKorea to Skorea for closing ceremony. Special Broadcast Service (Australia), October 5, 2014, at: http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2014/10/05/surprise-visit-nkorea-skorea-closing-ceremony

Since the North Korean delegation flew on one of Kim Jong Un’s two personal aircraft, it is reasonable to infer that DPRK wanted others to believe they represented him. However North Korea postponed the talks after exchanges of artillery fire and clashes over anti-DPRK pamphlet-laden balloon launches from the ROK in October 2014.[66]

Diplomatic-External Front

The DPRK long ago lost its diplomatic race with the ROK, and for the last two decades, has retrenched its international representation substantially, curtailing or withdrawing diplomats from many major capital cities.[67] Far from making a fresh diplomatic leap, it reverted to what observers call its habitual “pendulum diplomacy,” swinging from China to Russia for backing to balance its external dependencies, and seeking diplomatic space to gain time in the face of mounting external pressure to denuclearize and to accept international norms on a range of issues such as human rights.[68]

In 2014, three developments exhibited the DPRK’s steadily deteriorating diplomatic position. These were relations with China, relations with Japan, and relations with the international community on human rights.

The most important of these is the evident hostility in the DPRK’s relationship with China, its only remaining ally. North Korea is distancing itself from China, although both sides sustained people-people cultural exchanges throughout the year, leaving at least one door open for a future rapprochement. Although there is a wide range of opinion in Beijing as to how to handle the DPRK, there is no doubt that China’s top leadership is frustrated with the DPRK’s obdurate insistence that it develop nuclear weapons. This manifested directly in an unbalanced ratio of high-level official meetings; Chinese leaders met with South Korean leaders far more often and at far higher levels than they met with any North Koreans.

In 2014, the DPRK’s senior leadership had far fewer meetings with Chinese counterparts than in previous years. Its President and nominal head of state Kim Yong Nam, Vice Premier Kang Sok-ju and Foreign Minister Ri Su-Yong all transited Beijing en route to Africa (Kim Yong Nam), while Kang Sok Ju transited Beijing to and from Europe, the United States and South East Asia. None of them publicly met Chinese high level interlocutors during their transit. China’s Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin visited Pyongyang on February 20, 2014 followed by China’s envoy to the Six Party Talks, Wu Dawei, who reportedly travelled directly from Washington to Pyongyang, but was shunned by North Korean leaders meeting only with a low-ranking party official.[69] For the months following April, normal high-level exchanges between officials in Pyongyang and Beijing almost ground to a halt, except for contact at the DPRK’s Embassy in Beijing and occasionally China’s Ambassador in North Korea attended public events in North Korea. In terms of digital diplomacy, China’s Embassy in North Korea hasn’t added a single Korean-language article to its website since mid-2011.[70] Also reflecting the deteriorating relationship and in a break from past tradition and their special relationship, China and the DPRK did not exchange the usual pleasantries during momentous anniversaries such as the founding of their respective parties or national independence days. Nor did China send a high level delegation to Kim Jong Il’s birthday celebrations in February 2015.[71]

In a clear shift of strategic stance, China’s top leader, Xi Jinping went to South Korea first.[72] It is unknown when or if Xi will meet Kim Jong Un, let alone visit North Korea in his current position. Xi met with President Park Guen-hye several times in 2014. In contrast, no Chinese leader in the Politburo Standing Committee (China’s seven-person organ of supreme power) has met Kim Jong Un since he took power in 2011. The highest level meeting between any North Koreans and Chinese since 2011 was in March 2014. China’s President, Xi Jinping met North Korea’s President Kim Yong-nam on the sidelines of the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia.[73] But Kim Yong-nam is nominal head of state, while Xi Jinping is undisputed leader of all three major levers of power in China: the Party, military, and state.

Some influential on-line Chinese figures have foreshadowed that China would be none too upset if someone other than Kim were in charge, but China will not let North Korea fall into “chaos”.[74] Moreover, China uses the trade relationship to extract “full cost recovery” (to the extent possible) for the distasteful task of providing a security commitment to the DPRK in what Chinese leaders perceive to be in China’s interest. Thus, the trade relationship has been sustained for most of 2014 at similar levels to the previous year, although there has been a shift in the composition of this trade (away from anthracite exports and towards knitted and non-knitted textiles in DPRK exports to China, whereas textile-related production inputs have increased in Chinese exports to the DPRK.[75] China also reduced oil flows to the DPRK, with reported trade in crude oil dropping to zero for the first half of 2014,[76] and similar cuts to jet-fuel supplies. However, substantial oil flows in concessional and unreported channels. China was also irritated when the DPRK, for the third time in three years, captured a Chinese fishing vessel.[77]

However, we should not assume that this deterioration in the relationship was solely China’s choice. The DPRK also had little reason to embrace China given that Beijing had failed totally (from North Korea’s point of view) to move the White House off its rock of refusal to resume dialogue without the DPRK capitulating to its terms. Perhaps the most powerful symbolic expression of this displeasure at China’s failure to perform as an acceptable hegemon for the DPRK was the DPRK’s issuance of its proposal to resume Six Party Talks via Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natelagawa in June 2014.[78] One can imagine the muttering in the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs upon receiving a DPRK proposal via Jakarta, rather than Beijing playing the bridging role!

All in all, one would have to judge 2014 to be a fresh leap backwards for the DPRK’s key alliance, albeit recognizing that China is not about to “collapse” the DPRK in order to preserve China’s fundamental geo-strategic self interest.

The second key external development was the re-opening of talks with Japan’s conservative government on the abductee issue. Talks on this issue had an abrupt start-stop quality to them, but it is clear that Abe needs a foreign policy success to offset his many domestic political difficulties, as well as external problems such as the offshore islands confrontation with China and the comfort women issue. For its part, the DPRK can be expected to keep these talks alive in order to disconcert the ROK and to put pressure on Washington. Japanese reparations on the order of $10 billion (although the $10 billion likely would go to a managed international fund and not directly into Pyongyang’s coffers) might follow eventually from resolution of the issue, but no-one expects a breakthrough to occur on this front which entails the DPRK completing and providing Japan with the results of an internal investigation of Japanese abductees in the DPRK. That the DPRK deigned to respond to Abe’s overtures reveals as much its vulnerability on other fronts as it does strength in its external relations.

Finally, the UN Commission of Inquiry Report on Human Rights in the DPRK into the appalling state of human rights in the DPRK morphed from a political irritant when it was released in March to a central political problem for the DPRK in the third and fourth quarters of 2014.[79] The preparation of a draft UN General Assembly resolution[80] by the European Union and Japan calling on the UN Security Council to refer the matter to the International Criminal Court for possible indictment of Kim Jong Un for crimes against humanity led to an all-out campaign by DPRK diplomats to deflect this attack on Kim Jong Un’s international political persona. Given the centrality of the suryong, this task overwhelmed all other North Korean priorities in the last quarter of 2014, distracting their diplomats and leaders from other urgent imperatives confronting the DPRK with hard choices. North Korea’s sudden decision to release all three detained Americans should be seen in the context of their imperatives at the end of the year.

It should also be noted that neither China nor Russia were able to prevent the matter from being referred to the Security Council, but either China or Russia and likely both will use their veto power to prevent Kim Jong Un from being charged with crimes against humanity as suggested by the UN commission of enquiry

Cyber

The regime faced a final challenge to Kim Jong-un’s legitimacy in late December when Sony released a satirical movie, “The Interview”, which portrays an attempted assassination of Kim Jong Un, and the overthrow of the regime by a “Free North Korea” insurgency.[81] This symbolic confrontation was preceded by a cyber-attack and vandalism of Sony Pictures that the US government attributed to the DPRK, leading President Obama to threaten “proportional retaliation[82]” – although such a term has never been defined in a cyber context but could be construed as “proportionate” in accordance with the laws of war – and is apt to be misunderstood by all parties.[83] The DPRK denied it was responsible for the Sony attack and threatened its own retaliation, sans modifier.[84]

The US State Department asked China to shut down North Korean hacking on its soil or using communications systems transiting China.[85] On December 24, 2014, the internet connection to the DPRK shut down, possibly due to a denial of service attack,[86] an attack which the US State Department pointedly neither confirmed nor denied. [87] The following days saw more outages. The DPRK blamed the United States government[88], but anti-DPRK hackers also claimed responsibility.[89]

Given the short distance from symbolic and cyber warfare to kinetic and radioactive warfare in Korea, this event was significant, especially as cyber warfare can be conducted not only against networked military forces, but against critical infrastructure such as dams, power plants, hospitals, and data-intensive sectors dependent on record-keeping databases. And indeed, someone hacked into two South Korean nuclear power plants between December 15-21, 2014,[90] underscoring that the Korean peninsula remains a very dangerous place six decades after the guns fell silent when the armistice was signed.[91]

Conclusion

Far from “a year of sea changes, in which we will raise a fierce wind of making a fresh leap forward on all fronts,”[92] the DPRK appears have leapt into thin air without building foundations on which to land. Indeed, in many respects, it appears to be moving backwards by reverting to stale and failed formula from previous decades of juche (an ideology often taken to mean “self-reliance”) and the personal rule of the Kim regime. Nonetheless, the DPRK has proven itself resilient against external pressure and domestic shocks over many years, and events in 2014 did nothing to suggest that the DPRK is anything other than likely to survive for many years. As the year closes, the DPRK appears to biding its time, possibly to outwait the Obama presidency, and possibly to resume an aggressive and confrontational campaign against Park Guen Hye who will be a lame duck president in Seoul in 2015 and may be unable to deliver substantial progress in inter-Korean relations.

Our impression is that Kim Jong Un is learning on the job. In spite of fierce rhetoric, there were only low-level military clashes in 2014. The machinations involved in maintaining control of a state are demanding of any leader, let alone an inexperienced one in a pyramid of power like that found in North Korea. His “day job” leaves little time for Kim to focus on external relations. The continuation of an extreme level of personalized, centralized decision-making as embodied in Kim Jong Un also means that most decisions that need to be made on domestic issues never get made, leaving cadres and officials guessing or alternatively leaving them scrambling to implement decisions that defy market basics. The result, unless they are forced to act by corruption or by deprivation, is most people are busy doing nothing in order to avoid risk.

Thus, a key question for Kim remains whether he can deliver on his promise to improve the lot of ordinary and middle-ranking North Koreans before generational change overtakes the regime with a massive revulsion against their deprivation. This is a race against time, against the cumulative effects of sanctions, against the institutional and cultural resistance to the structural changes needed to kick-start the economy, and against the DPRK’s deteriorating conventional military force.

Arguably the DPRK will be remain at the bottom of its very deep hole of isolation sitting on top of a small pile of nuclear weapons and a large pile of conventional weapons, but unable to dig its way out of this hole without external support. This support in turn will not be forthcoming so long as the DPRK does not adjust its approach to overcoming the hostility that besets all its major external relationships. It showed no signs of innovation in 2014 in its fundamental approach to ending this hostility, which is based on a realist world view in which little matters other than the leader, political ideology, and military power.

Instead, Kim Jong Un and the DPRK continue trying to exploit the vagaries of the evolving balance of power as the foundation of its security and even survival. As the world’s relatively unconstrained great power becomes enmeshed in webs of interdependence, adherence to universal norms, construction of trade regimes and legal frameworks, codification of practices, and shared public goods all created in the course of globalization of almost every aspect of human existence, the realist basis for the DPRK’s small power survival strategy has shrunk. Like the ROK, the DPRK has to find a post-modern pathway to transcend realist-based survival strategies that have been superseded by political, economic, technological, and even cultural forces that are bigger than any state, even the United States.

If the DPRK does not break out of its downward spiral, it will descend eventually into the vortex of mass politics exercised in a traditional, orthodox Korean manner that signals the end of Kim’s rule and even the endgame of the regime. The only way out of this cul de sac is to find niche roles in the international affairs that swirl around the Korean Peninsula whereby the DPRK can add value and contribute to joint public goods. Whether Kim Jong Un can channel his inner self to ignite a slow motion revolution on many fronts rather than leaping freshly into thin air and crash landing depends on the extent to which the external powers engage Kim, shift his decision-making calculus, and open up fresh options.

Left to his own devices, it is unlikely that this reorientation will happen. The DPRK’s performance in 2014 does not portend a bright future in 2015.

Banner image credit: Chris Greacen, Nautilus Institute photograph

III. REFERENCES

[1] Kim Jong Un, “New Year Address,” Jan. 1, 2014, Rodong Sinmun English translation appended to: Peter Hayes and Roger Cavazos, “Kim Jong Un’s “Fresh Leap Forward” 2014 New Year Speech”, NAPSNet Special Reports, January 01, 2014, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/kim-jong-uns-fresh-leap-forward-2014-new-year-speech/

[2] J Dana Stuster, “And then there were two… Kim Jong Il’s dwindling inner circle”, Foreign Policy Passport. December 13, 2013, http://blog.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2013/12/13/and_then_there_were_two_kim_jong_ils_dwindling_inner_circle

[3] Kevin Stahler, “North Korea-China Trade Update: Coal Retreats, Textiles Surge”, North Korea: Witness to Transformation blog, October 27, 2014 as: http://blogs.piie.com/nk/?p=13578#comment-120021

[4] The Bank of Korea, Gross Domestic Product Estimates for North Korea in 2013. June 27, 2014, http://www.bok.or.kr/contents/total/eng/boardView.action?menuNaviId=634&boardBean.brdid=14033&boardBean.menuid=634

[5] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Food outlook: Biannual report on global food markets” October 2014, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4136e.pdf

[6] Alisa Tang, “N. Korea may achieve self-sufficiency in cereals in 2014, FAO says”, Thomson Reuters Foundation, Mar 26, 2014, http://www.trust.org/item/20140326133720-v8fe0/

[7] Stephan Haggard, Daniel Pinkston, Kevin Stahler, Clint Work. “Interpreting North Korea’s Missile Tests: When is a Missile Just a Missile?”, Witness to Transformation blog, October 7, 2014, http://blogs.piie.com/nk/?p=13532

[8] Yonhap News Agency, “All relatives of Jang executed too: sources”, January 26, 2014, http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/northkorea/2014/01/26/4/0401000000AEN20140126000800315F.html

[9] Stephan Haggard, Luke Herman and Jaesong Ryu, “Political Change in North Korea” Asian Survey 54:4(July 2014); John Ishiyama, “Assessing the leadership transition in North Korea: Using network analysis of field inspections, 1997 – 2012” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 47 (2014) 137-146

[10] “Kim Jong-un is a puppet” in the eyes of North Korean elite, New Focus International, March 7, 2014, at: http://newfocusintl.com/kim-jong-un-puppet-north-korean-elite/

[11] John Ishiyama, “Assessing the leadership transition in North Korea: Using network analysis of field inspections, 1997 – 2012” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 47 (2014) 137-146; Stephan Haggard, Luke Herman and Jaesong Ryu, “Political Change in North Korea” Asian Survey 54:4(July 2014)

[12] Yoon Sangwon, “What’s up with North Korea’s Kim? It’s a mystery to CIA”, Bloomberg News, October 9, 2014, at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-10-09/what-s-up-with-north-korea-s-kim-it-s-a-mystery-to-cia.html; David Maxwell, “Kim Jong-un: Has the North Korean dynasty fallen?” Fortuna’s corner, October 9, 2014 at, http://fortunascorner.com/2014/10/09/kim-jong-un-has-the-north-korean-dynasty-fallen/

[13] Nick Eberstadt, “North Korea merry-go-round” American Enterprise Institute October 9, 2014 at: http://www.aei.org/publication/north-korea-merry-go-round/ ; Jonathan D. Pollack, “Was Kim Jong-un’s disappearing and reappearing act ever a mystery?” The Brookings Institute, October 15, 2014, at: http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2014/10/15-kim-jong-un-disappearing-reappearing-act-pollack

[14] Ruediger Frank, “The SPA session of April 2014: spotlight on Sports and Economic and Trade Zones”, 38North, April 23, 2014 at: http://38north.org/2014/04/rfrank042314/

[15] Inter-Parliamentary Union, “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea” July 3, 2014, as: http://www.ipu.org/parline/reports/2085_E.htm

[16] KCNA, “1st Session of the 13th SPA of DPRK held”, April 9, 2014, at: http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2014/201404/news09/20140409-46ee.html;

KCNA, “2nd Session of the 13th Supreme People’s Assembly of DPRK held”, September 25, 2014, at: http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2014/201409/news25/20140925-30ee.html

[17] All North Korea budget figures in this section come from “Report on Implementation of State Budget for 2013 and State Budget for 2014”, (North) Korea Central News Agency, April 9, 2014 as http://kcna.co.jp/item/2014/201404/news09/20140409-09ee.html

[18] On the three economies, see Lee Young-sun, Yoon Deok-ryong, “The Structure of North Korea’s Political Economy: Changes and Effects,” in Ahn Choong-yong, Nicholas Eberstadt, Lee Young-sun, A New International Engagement Framework For North Korea? Contending Perspectives, Korea Economic Institute of America, 2004, at: http://keia.org/sites/default/files/publications/04Deok-ryong.pdf

[19] For a good overview of the jangmadang see Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, “The Winter of their Discontent: Pyongyang attacks the market” Policy Brief PB10-1, January 2010, Peterson Institute for International Economics, as, http://www.petersoninstitute.org/publications/pb/pb10-01.pdf

[20] KCNA, “Economic Development Zones to be Set up in Provinces of DPRK”, July 23, 2014, at: http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2014/201407/news23/20140723-24ee.html

[21] Seong Yeon-cheol, “Report: China-North Korea bridge opening postponed indefinitely” The Hankyoreh, November 1, 2014 at: http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_northkorea/662478.html

[22] “Kaesong Industrial Complex One Year after Resuming Operations”, Institute for Far Eastern Studies, NK Brief 14-09-22, September 26, 2014 as http://ifes.kyungnam.ac.kr/eng/FRM/FRM_0101V.aspx?code=FRM140926_0001

[23] Ruediger Frank, “The SPA session of April 2014,” op cit.

[24] Peter Hayes and Roger Cavazos, Kim Jong Un’s On The Spot Guidance Emphasis in 2014. Forthcoming.

[25] Andrei Lankov, “North Korea’s elites are a threat to Kim Jong Un”, Bloomberg View, October 13, 2014 as http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2014-10-13/north-korea-s-elites-are-a-threat-to-kim

[26] Steven Borowiec, “North Korea reportedly closing borders to tourists due to Ebola fears” The Los Angeles Times, October 23, 2014 as, http://www.latimes.com/world/asia/la-fg-north-korea-tourists-20141023-story.html

[27] Shuan Sim, “North Korea lifts Ebola travel restrictions to boost tourism”, International Business Times, March, 2, 2015, at: http://www.ibtimes.com/north-korea-lifts-ebola-travel-restrictions-boost-tourism-1833772

[28] James Pearson, “N. Korea warns diplomats under Ebola quarantine: no more parties”, Reuters, February 13, 2015, at: http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/02/13/us-northkorea-ebola-idUSKBN0LH0SS20150213

[29] Espen Bjertness and Ahmed Ali Madar, “North Korea: a challenge for global solidarity”, The Lancet, Volume 383, Issue 9926, April 19, 2014, at: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2814%2960677-2/fulltext?elsca1=ETOC-LANCET&elsca2=email&elsca3=E24A35F

[30] Hannah Bloch, “Why is North Korea Freaked Out About The Threat of Ebola?”, National Public Radio, 31 October 2014, at: http://www.npr.org/blogs/goatsandsoda/2014/10/31/360195471/why-is-north-korea-freaked-out-about-the-threat-of-ebola

[31] A study of CO poisoning in the ROK is applicable to the DPRK today. However, there is no DPRK data for the rate of CO poisoning, but the authors (Hayes) have been informed by DPRK health specialists that it is a common event. Kim Ok Joo and Pak Seo Hong, “A social history of carbon monoxide poisoning in Korea in 1960s: from an accident due to to carelessness to a social disease,” Korean Journal of Medical History, Volume 21, Issue 2, August 2012, at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22948168

[32] Shuichi Doi, “Japan at risk as malaria epidemic in North Korea spreads,” Asian Wall St Journal, January 7, 2014, at: http://ajw.asahi.com/article/asia/korean_peninsula/AJ201401070008 and Yo Han Lee, Seok-Jun Yoon, Young Ae Kim, Ji Won Yeom, In-Hwan Oh, “Overview of the Burden of Diseases in North Korea,” Journal of Preventive Medicine & Public Health, May 2013; 46(3): 111–117, published online May 31, 2013, at: http://jpmph.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.3961/jpmph.2013.46.3.111

[33] Julian Ryall, “North Korea asks UN for help with foot-and-mouth outbreak,” The Telegraph, February 26, 2014: at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/northkorea/10662016/North-Korea-asks-UN-for-help-with-foot-and-mouth-outbreak.html

[34] BBC News, “North Korea ‘drops Kim Il-sung from new banknotes’”, 11 August 2014, as http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-news-from-elsewhere-28743954

[35] DailyNK, Market Trends, updated bi-weekly. As http://www.dailynk.com/english/market.php?page=2&cataId=

[36] Ibid

[37] Yong Kwon, “Assessing Cause and Effect: Food price stability and the Korean People’s Won” Iron and Rice, 6 January 2014, as http://nkfood.wordpress.com/2014/01/06/assessing-cause-and-effect-food-price-stability-and-the-korean-peoples-won/

[38] Scott Snyder, “North Korea’s Growing Trade Dependency on China: Mixed Strategic Implications” Asia Unbound blog on Council on Foreign Relations, June 15, 2012, as, http://blogs.cfr.org/asia/2012/06/15/north-koreas-growing-trade-dependency-on-china-mixed-strategic-implications/

[39] Michelle, FlorCruz, “Russia to Revamp North Korea’s Rail System, Eyes Mineral Resources” International Business Times, 30 October 2014 as, http://www.ibtimes.com/russia-revamp-north-koreas-rail-system-eyes-mineral-resources-1716262

[40] V. Soldatkin, “Russia writes off 90 percent of North Korea debt, eyes gas pipeline,” Reuters, April 19, 2014, at: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/04/19/russia-northkorea-debt-idUKL6N0NB04L20140419

[41] D. Von Hippel and P. Hayes, “Energy Needs in the DPRK”, NAPSNet Policy Forum, August 12, 2014, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/energy-needs-in-the-dprk/

[42] Seol Song Ah, “Solar Panels Shine New Light on NK,” Dailynk.com, October 24, 2014, at:

http://www.dailynk.com/english/read.php?cataId=nk01500&num=12465

[43] Lee Yong Suk, “Countering Sanctions: The Unequal Geographic Impact of Economic Sanction in North Korea”, Freeman Spogli Institute of International Studies, Stanford University, 26 August 2014, at http://aparc.fsi.stanford.edu/publication/countering-sanctions-unequal-geographic-impact-economic-sanctions-north-korea

[44] Shannon Tiezzi, “US, South Korea Announce Joint Military Drills”, The Diplomat February 11, 2014 at: http://thediplomat.com/2014/02/us-south-korea-annouce-joint-military-drills/

[45] Ashley Rowland and Yoo Kyong Chang, “US, South Korea quietly end Ulchi Freedom Guardian exercise”, Stars and Stripes, August 28, 2014, at: http://www.stripes.com/news/pacific/us-south-korea-quietly-end-ulchi-freedom-guardian-exercise-1.300309

[46] For a brief overview of all launches in 2014 up to October Stephan Haggard, Daniel Pinkston, Kevin Stahler, Clint Work. “Interpreting North Korea’s Missile Tests: When is a Missile Just a Missile?”, Witness to Transformation blog, October 7, 2014, http://blogs.piie.com/nk/?p=13532

[47] For KN10, “N. Korea launches new model of tactical rockets: Seoul source”, Yonhap News Agency, August 18, 2014 as, http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/full/2014/08/18/20/1200000000AEN20140818004000315F.html

[48] For KN02, “N. Korea developing anti-ship missile” Chosun Ilbo, 14 Oct 2014 as, http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2013/10/14/2013101400683.html

[49] For KN08 Choe Sang-hun, “Satellite shows North Korea has upgraded launch station”, New York Times, Oct 2, 2014, as http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/03/world/asia/satellite-shows-north-korea-has-upgraded-launch-station.html?_r=0

[50] Peter Hayes and Roger Cavazos, “North Korea’s Nuclear Force Roadmap: Hard Choices,” NAPSNet Special Report, March 2, 2015, at: https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/north-koreas-nuclear-force-roadmap-hard-choices/

[51] David Albright and Christina Walrond, North Korea’s Estimated Stocks, op cit, Table 2, page 36.

[52] Joel S. Wit and Sun Young Ahn, “North Korea’s Nuclear Futures: Technology and Strategy”, US-Korea Institute at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, February 26, 2015, at: http://38north.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/NKNF-NK-Nuclear-Futures-Wit-0215.pdf

[53] For incredible (non-credible) threats in greater detail see, Hayes and Cavazos, “North Korea’s nuclear roadmap: Hard Choices”, NAPSNet Special Report, March 2, 2015, at: https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/north-koreas-nuclear-force-roadmap-hard-choices/

[54] David Wright, “North Korea’s Satellite,” All Things Nuclear, Union of Concerned Scientists, December 15, 2012, at: http://allthingsnuclear.org/north-koreas-satellite/; William Broad, Choe Sang-Hun, “Astronomers Say North Korean Satellite Is Most Likely Dead,” New York Times, December 17, 2012, at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/18/world/asia/north-korean-satellite.html?_r=0

[55] M. Weisgerber, “US Doesn’t Know If North Korea Has a Nuclear Missile,” Defense One, October 24, 2014, at: http://www.defenseone.com/threats/2014/10/us-doesnt-know-if-north-korea-has-nuclear-missile/97364/?oref=defenseone_today_nl

[56] Sam Kim and David Tweed, “North Korean Submarine Threat Overstated, Arms Analysts Say”, Bloomberg news November 3, 2014, at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-11-03/missile-firing-submarines-remain-no-mean-feat-for-north-korea.html

[57] KCNA, “Rodong Sinmun calls for Korea’s Reunification Based on Three Principles”, March 14, 2014 at: http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2014/201403/news14/20140314-06ee.html

[58] KCNA, “Five-Point Policy of Great National Unity Should be Implemented” November 1, 2014 at: http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2014-11-01-0003&chAction=T

[59] South-North Joint Declaration June 15, 2000, at: http://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/file/resources/collections/peace_agreements/n_skorea06152000.pdf

[60] Yi Whan-woo, “Concrete plan to win NK trust key for inter-Korean unification”, Korea Times, October 2, 2014 at: http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2014/11/485_165553.html

[61] Choe Sang-hun, “Amid Hugs and Tears, Korean Families Divided by War Reunite, New York Times, February 20, 2014 at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/21/world/asia/north-and-south-koreans-meet-in-emotional-family-reunions.html?_r=0

[62] Choe Sang-hun, “North Korea Rejects Plans for More Family Reunions,” New York Times, March 6, 2014, at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/07/world/asia/north-korea-rejects-plans-for-more-family-reunions.html

[63] Jon Herskovitz and Kim Junghyun, “South Korean tourist shot dead by North soldier”, Reuters July 11, 2008 as, http://www.reuters.com/article/2008/07/11/us-korea-north-shooting-idUSSEO14908720080711

[64] “North Korea seizes South’s Mount Kumgang resort assets”, BBC News Asia-Pacific, August 22, 2011 as, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-14611873

[65] “Russia to extend Trans-Eurasian rail project to Korea, RT.com, June 6, 2014, at: http://rt.com/business/164116-russia-railway-north- korea/ and Xinhua,”DPRK launches railway remodeling project with help ofRussia,” October 22, 2014, at: http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/n/2014/1022/c90777-8798379.html

[66] Xinhua News Agency, “S. Korea regrets over DPRK’s refusal to inter-Korean dialogue”, November 2, 2014 as: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/world/2014-11/02/c_133760507.htm; Talk Vietnam, “ROK decries DPRK’s refusal of inter-Korean dialogue” November 3, 2014 as: http://www.talkvietnam.com/2014/11/rok-decries-dprks-refusal-of-inter-korean-dialogue/

[67] P. Hayes, “North-South Korean Elements of National Power,”: NAPSNet Special Reports, April 27, 2011, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/north-south-korean-elements-of-national-power/

[68] Sung Ki-Young, “Hwang Pyong-so’s Visit to South Korea and Comments on Prospective Negotiations with North Korea, Center for Unification Policy Studies, Seoul, October 7, 2014, at: http://www.kinu.or.kr/eng/pub/pub_05_01.jsp?page=1&num=163&mode=view&field=&text=&order=&dir=&bid=EINGINSIGN&ses=&category=

[69] A. Cathcart, “Tuning Out Beijing’s Six-Party Drumbeat: Wu Dawei in Pyongyang,” April 1, 2014, at: http://sinonk.com/2014/04/01/wu-dawei-pyongyang-six-party/

[70] Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, at: http://kp.china-embassy.org/kor/

[71] Yonhap News, “China sent no delegation to birthday anniversary of Kim Jong-il”, February 17, 2015, at: http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/national/2015/02/17/18/0301000000AEN20150217008600315F.html

[72] Jane Perlez, “Chinese President’ Visit to South Korea Is Seen as Way to Weaken U.S. Alliances”, July 2, 2014, at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/03/world/asia/chinas-president-to-visit-south-korea.html?_r=0

[73] Chosun Ilbo, “Kim Jong-un’s Aunt ‘Loses Seat in Rubber Stamp Parliament’”, March 14, 2014, at: http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2014/03/14/2014031400703.html.

[74] Ding Dong丁咚, “Why doesn’t China let North Korean fall into internal chaos” “中国为何不允许朝鲜内乱?”Phoenix media blog, October 10, 2014 as, http://blog.ifeng.com/article/34192112.html

[75] Kevin Stahler, “North Korea-China Trade Update: Coal Retreats, Textiles Surge,” ,” North Korea: Witness to Transformation blog, October 27, 2014, at: http://blogs.piie.com/nk/?p=13578

[76] Marcus Noland and Kevin Stahler, “The (non-) Embargo,” North Korea: Witness to Transformation blog, August 14, 2014, at: http://blogs.piie.com/nk/?p=13416

[77] A. Cathcart, “Odyssey of Extortion: Chinese Press Coverage of the North Korean boat hijacking”, September 25, 2014, at: http://sinonk.com/2014/09/25/hijacking-dalian-north-korea/

[78] A. Panda, “Will Indonesia Save the Six Party Talks? North Korea wants Indonesia to potentially advocate on its behalf on the world stage,” The Diplomat, August 16, 2014, at: http://thediplomat.com/2014/08/will-indonesia-save-the-six-party-talks/

[79] United Nations, “Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea”, March 17, 2014, at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/CoIDPRK/Pages/CommissionInquiryonHRinDPRK.aspx

[80] Louis Charbonneau, “U.N. Draft Urges ICC Referral for North Korea, but Pyongyang fights back”, Business Insider, October 9, 2014 as:: http://www.businessinsider.com/r-un-draft-urges-icc-referral-for-north-korea-but-pyongyang-fights-back-2014-10

[81] Peter Hayes, “Strategic Negligence and the Sony Sideshow”, NAPSNet Policy Forum, December 22, 2014, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/strategic-negligence-and-the-sony-sideshow/

[82] The White House, transcript, President Obama’s Year End Press Conference, December 19, 2014, http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/texttrans/2014/12/20141219312317.html#axzz3MZ9YXIYp

[83] David Sanger, Michael Schmidt, Nicole Perlroth, “Obama Vows a Response to Cyberattack on Sony,” New York Times, December 19, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/20/world/fbi-accuses-north-korean-government-in-cyberattack-on-sony-pictures.html?emc=edit_th_20141220&nl=todaysheadlines&nlid=57976564&_r=1

[84] KCNA, “U.S. Urged to Honestly Apologize to Mankind for Its Evil Doing before Groundlessly Pulling up Others,” December 21, 2014, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2014/201412/news21/20141221-14ee.html

[85] D. Sanger, Nicole Perlroth, Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Asks China to Help Rein In Korean Hackers,” New York Times, December 20, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/21/world/asia/us-asks-china-to-help-rein-in-korean-hackers.html

[86]Nicole Perlroth, David Sanger,“North Korea Loses Its Link to the Internet,” New York Times, December 22, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/23/world/asia/attack-is-suspected-as-north-korean-internet-collapses.html?partner=rss&emc=rss&smid=tw-nytimesworld&_r=1

[87] Jim Cowie, “Someone Disconnects North Korea – Who?” December 23, 2014, at:

http://research.dyn.com/2014/12/who-disconnected-north-korea/

[88] Associated Press, “N. Korea Uses Racial Slur Against Obama Over Hack,” December 27, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2014/12/27/world/asia/ap-as-nkorea-sony-hacking.html

[89] Raphael Satter, “North Korea’s Internet outages continue as disruption’s cause remains a mystery,” Associated Press, December 24, 2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2014/12/24/world/europe/ap-eu-nkorea-mystery-outage.html

[90] “Hacker Reveals Classified Info About Nuclear Reactors,” Chosun Ilbo, December 22, 2014, at: http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2014/12/22/2014122201204.html

[91] Peter Hayes, “Strategic Negligence and the Sony Sideshow”, NAPSNet Policy Forum, December 22, 2014, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/strategic-negligence-and-the-sony-sideshow/

[92] Kim Jong Un, “New Years Speech,” op cit.

One thought on “North Korea in 2014: A Fresh Leap Forward Into Thin Air?”