SHIN YOUNG-JEON

MARCH 3, 2021

I. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, Shin Yeong-jeon notes that both the DPRK and the United States say “No Problem” when it comes to the Covid-19 pandemic in the DPRK: “The DPRK is voicing “No Problem” despite the economic sanctions of the United States and the United Nations. The United States also argues that US-led international sanctions are not the cause of humanitarian disasters in the DPRK. This “No Problem” collusion pattern can invite dangerous consequences, which not only distorts the facts but can also lead to many victims, making intervention difficult by missing confirmation timing for catastrophic situations such as famine. This is similar to the “No Problem” collusion pattern in the North Korean famine of the late 1990s.” In light of the DPRK’s emerging Covid-19 and food crises, he concludes that “The DPRK needs to establish a more open cooperation system with the international community including the ROK and the United States. The United States also needs to make sure that the DPRK is not in extreme situations or makes its worst choices. To this end, it is necessary to change the policy on the Korean Peninsula that the Obama and Trump administrations took in the past, and the core of this is to proceed with step-by-step denuclearization while opening the possibility of peace and prosperity through the vitalization of exchanges between the two Koreas.”

Shin Young-jeon is Professor, Department of Preventive Medicine, at Hanyang University School of Medicine, Seoul Korea.

This essay is a working paper prepared for the The 75th Anniversary Nagasaki Nuclear-Pandemic Nexus Scenario Project October 31-November 1, and November 14-15, 2020 Co-sponsored by Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University (RECNA), the Nautilus Institute, Asia Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament and presented to Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) in the Asia-Pacific Workshop December 1 – 4, 2020, organized and sponsored by the Asia Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (APLN).

The essay may be downloaded in PDF format here. It is published also by RECNA here and by APLN here

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

This report is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here.

Banner image: Sophia Mauro for Nautilus Institute. This graphic shows the pandemic distribution from COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) on September 25, 2020; and the nuclear threat relationships between nuclear armed states.

II. NASPNET SPECIAL REPORT BY SHIN YEONG-JEON

THE DPRK’S COVID-19 OUTBREAK AND ITS RESPONSE

MARCH 3, 2021

Summary

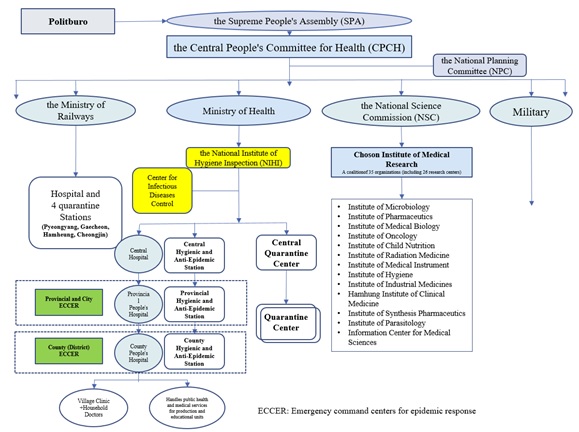

On January 25, 2020, the DPRK shut down its border, switched to a state-run emergency quarantine system, organized a pan-ministerial organization, the Central People’s Committee for Health (CPCH), and established emergency command centers for epidemic response (ECCER) in provincial, county, and Ri-levels. Until now, it has continued to take the strongest Covid-19 quarantine measures in the world, including restricting cross border and regional movement.

The DPRK responded swiftly and strongly to past major outbreaks such as SARS (2002-2003), measles (2006-2007), swine flu (2009-2010), Ebola (2013-14), and MERS (2015), as well as the periodic outbreak of typhoid fever, cholera, etc. In response to the coronavirus outbreak, the DPRK drew on its experience to implement aggressive measures such as border blocking, strengthening disinfection, and quarantine, as in response to past large-scale epidemic threats.

On January 25, 2020, the DPRK shut down its border, switched to a state-run emergency quarantine system, organized a pan-ministerial organization, the Central People’s Committee for Health (CPCH), and established emergency command centers for epidemic response (ECCER) in provincial, county, and Ri-levels.[1] Until now, it has continued to take the strongest Covid-19 quarantine measures in the world, including restricting cross border and regional movement.

The DPRK responded swiftly and strongly to past major outbreaks such as SARS (2002-2003), measles (2006-2007), swine flu (2009-2010), Ebola and (2013-14), and MERS (2015), as well as the periodic outbreak of typhoid fever, cholera, etc. In response to the coronavirus outbreak, the DPRK drew on its experience to implement aggressive measures such as border blocking, strengthening disinfection, and quarantine, as in response to past large-scale epidemic threats. The Covid-19 epidemic[2] differed in the following ways:

- The scale of the outbreak is more global and longer-term.

- Economic sanctions imposed by the United Nations and the United States have made it difficult to procure and move quarantine supplies.

- China was unable to actively help DPRK in the early stages of the pandemic because China had its own difficulties with Covid-19.

- In the past, the DPRK government has asked the ROK for Tamiflu and thermal detectors and received help, while the DPRK have been adamantly refusing the ROK’s help this time due to changes in political circumstances.

The DPRK is one of the few countries in the world to maintain its official position that, as of the end of December 2020, no Covid-19 infections have occurred. It is still controversial whether there have been no Covid-19 infections in the DPRK. There are several reasons why the DPRK continues to make this claim. First, it seems that high rates of infection did not occur until recently. Second, in the early stages of the epidemic, testing kits were scarce, so even if an infection occurred, it could not be confirmed. Third, the DPRK is immensely proud of its health care system. At a general meeting of the Central Committee of the North’s ruling Workers’ Party in December 2019, Chairman Kim Jong-un noted, “Health care system is a major symbol of the superiority of North Korean socialism that can be directly felt by the people.” Fourth, there seems to be some concern in the DPRK’s leadership that public fear of the epidemic could threaten the political stability of the DPRK’s regime. Lastly, infectious diseases such as cholera and bacillary dysentery occur in all groups, are highly contagious, and the symptoms are unusual, while Covid-19 appears mainly in the form of “quiet death” in older people.

The Trend and Response of the DPRK’s Covid-19 Epidemic

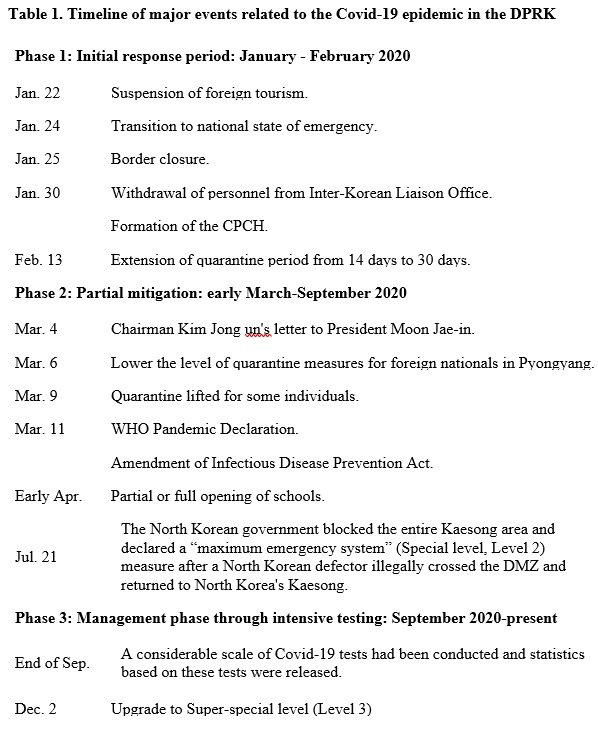

Phase 1: Initial response period: January—February 2020

So far, the trend and response of the North’s Covid-19 can be divided into three major stages. The DPRK’s initial response to Covid-19 was quick and powerful. On January 22, foreign tourism was halted, the state was switched to the national emergency quarantine system (January 24), and border closure measures were imposed (January 25). On January 30, the DPRK requested the withdrawal of South Korean officials from the inter-Korean liaison office in Kaesong, and North Koreans also withdrew.

As a central organization was formed, the Central People’s Committee for Health (CPCH), emergency command centers for epidemic response (ECCER) were established in cities, provinces, counties, and ri. Immediately after its formation, CPCH proposed to extend the incubation period of Covid-19 from 14 days to 30 days, and the Standing Committee of the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) approved it (February 13).

The Central People’s Committee for Health (CPCH) is a pan-ministerial organization organized in the event of a large-scale public health crisis, such as the nationwide epidemic of infectious diseases. It was also organized and operated in the past during the swine-origin influenza A epidemic. Interestingly, the executive responsibility of this organization is vested not in the Ministry of Health but in the National Planning Committee. The National Planning Committee (NPC) is generally an organization that oversees the DPRK’s economic policy. This designation shows that departments with large financial capabilities and authority are entrusted with the overall coordination of the pandemic, and that they are considering the impact of a massive public health crisis on the national economy.

The responsibility for the management of infectious diseases with the Ministry of Health is led by the National Institute of Hygiene Inspection (NIHI), the most powerful unit in the ministry. Under the Ministry of Health, there are sanitary quarantine stations and checkpoints as well as provincial, municipal, and county hospitals and grade clinics. The various health and medical research institutes are not under the Ministry of Health but under the National Science Commission (NSC).

One of the largest state-run organizations in the DPRK, the Ministry of Railways has its own hospital and four quarantine stations. Military organizations also have separate health care and quarantine systems (figure 1).

Figure 1. The DPRK’s national emergency response system for epidemics

This early phase was a time when not only the DPRK but also China and the ROK were in turmoil as the Covid-19 epidemic spread in China and the ROK. Even the ROK and China could not afford to support the DPRK because they lacked diagnostic kits and equipment for their own use. Covid-19 infection can be confirmed only through diagnostic equipment, and a diagnostic kit is needed to determine whether a patient is fully recovered. By the end of August 2020, the DPRK was fighting Covid-19 with very few diagnostic kits. To cope with the problem, the DPRK quickly extended its quarantine period from 14 days to 30 days, which was a reasonable decision.

The DPRK government promulgated a 10-day quarantine period for customs clearance along with border closure. Active quarantine promotion was carried out through various mass media, including street promotion. The DPRK government continued to broadcast on the streets about Covid-19 prevention using vehicles equipped with loudspeakers. The state-run newspaper, Rodong Shinmun, featured many more articles on Covid-19 than it had during previous Ebola and H1N1 flu epidemics.

The government actively encouraged the production of disinfectants, such as sodium hypochlorite solution NaClO or NaOCl, and executed a disinfection operation. Case finding was based on the existing Hodamdang doctor (household doctor) system. Each household doctor visited the homes of about 500 residents to find patients with high fever who were suspected of having Covid-19. As of May 5, 2020, the Rodong Sinmun encourages the activities of Hodamdang doctors as follows:

(They said), “It is raining or snowing, and the sound of the doctors in charge visiting the houses and knocking on the door should not stop even a day, and they are carrying out the hygiene propaganda and disinfection projects responsibly along with screening checks for the local residents.” (Rodong Shinmun, May 5, 2020)

At the beginning of the epidemic, however, there were no test kits, so it was only possible to check for high fever and infection. Moreover, visiting medical personnel did not have enough protective equipment, and, even if they found a suspected patient, they had nothing to recommend except self-isolation, so there was a limit to the results achieved by active case finding. Similarly, the government identified high-temperature patients by augmenting “quarantine posts”[3] located where there are many people and means of transportation, such as provincial, city, and county border points and road intersections, but they had limited ability to follow-up except to order self-isolation.

The North Korean authorities managed the subjects of intensive management by dividing them into “person under medical observation” and “Uijinja” (suspected patient).

| “Person under medical observation” has no symptoms of disease, but has traveled, lived, and contacted infected patients for 24 days (incubation period) before the onset of the disease.

“Uijinja (suspected patient)” is suspected of having an infectious disease like |

As in the past, the DPRK has responded to the Covid-19 epidemic by focusing on the isolation of suspected patients. During this period, the collective isolation of foreigners used hotels in several provinces, including Pyeongseong Jangsusan hotel.

In the case of group quarantine, food and household goods had to be supplied to those quarantined for about 30-40 days, which is difficult to achieve in the DPRK, because of its struggling economy. Therefore, persons under medical observation or Uijinja (suspected patients)” are quarantined/isolated in their own home.

Due to the epidemic of infectious diseases, movement to other areas was in principle prohibited, and, if necessary, movement was made possible only by obtaining a health certificate as well as a move permit. Insufficient protective equipment such as “functional masks” left medical personnel at risk of infection. North Koreans used a regular face mask with less protection, made of cotton or paper, not a special mask that could block fine aerosols.[4] Furthermore, there were production challenges because of a lack of raw materials for masks.

The biggest deficit was treatment equipment. There are hardly any quarantine rooms in the DPRK equipped with negative pressure facilities. Because of the lack of artificial respirators and other expensive treatments, intensive treatment was difficult. The DPRK encouraged the production of anti-HIV products, Interferon and Interleukin, which were developed in the DPRK, but it seems it was impossible to secure enough. Instead, it encouraged the production of traditional medicine products using herbs such as burdock to increase immunity.

Phase 2: Partial mitigation: early March to September 2020

On March 4, the DPRK’s Chairman Kim Jong-un sent a letter to ROK President Moon Jae-in. It extended sympathy to the South Korean people suffering from Covid-19. It might be argued that the letter was an oblique request for South Korean help in responding to Covid-19. However, the DPRK government eased restrictions imposed on foreigners in Pyongyang city starting in early March, lifted quarantine measures for some people, partly opened school from early April, and allowed school opening entirely in June. Therefore, Chairman Kim Jong-un’s personal letter in early March may have originated less from a need for ROK support and more from the DPRK’s assertion of confidence that it is possible to manage Covid-19 to some extent.

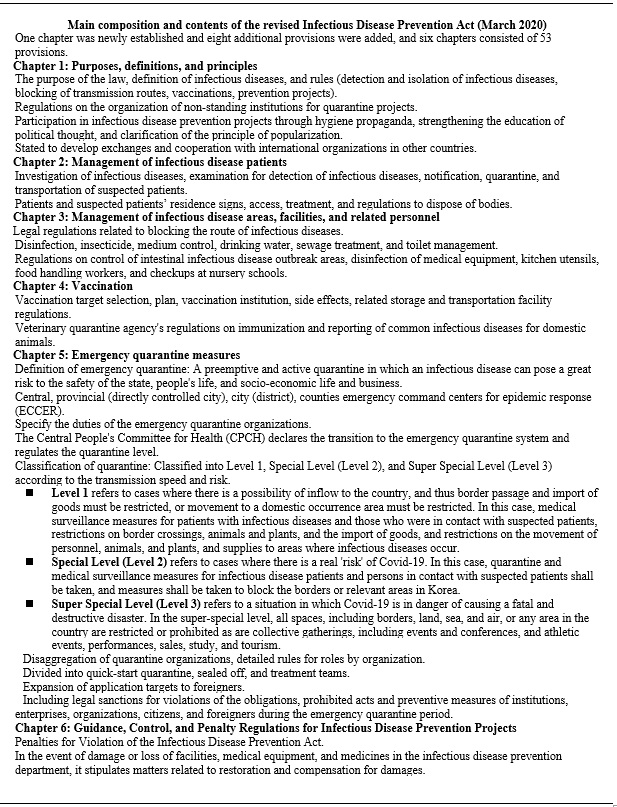

Even during this phase, measures such as border closure, restriction of inter-regional movement, disinfection, case finding, and education promotion were continuously carried out. In addition, the existing infectious disease prevention methods were revised around March to create a legal basis to strengthen countermeasures against infectious diseases.

In the provisions for emergency quarantine measures in Chapter 5 of the revised “Infectious Disease Prevention Act,” when an infectious disease poses a great risk to the safety of the state, the safety of people’s lives, and socio-economic life, the Central People’s Health Guidance Committee may declare the transition to the emergency quarantine system and establish the quarantine level to carry out highly organized pre-emptive and active quarantine projects.

The national or regional situation is classified according to the transmission speed and risk of infectious diseases into Level 1, Special Level (Level 2), and Super Special Level (Level 3), and appropriate responses are specified. For example, the Special Level refers to a situation in which Covid-19 may lead to a fatal and devastating disaster. In the Super Special Level, restrictions are placed on all spaces, including the border, land, sea, and air, or the relevant areas in Korea, and collective gatherings, including events and meetings, sports games, performances, sales, study, and tourism, among others. In particular, the revised bill extended its application to foreigners, and included legal sanctions when organizations, enterprises, citizens, and foreigners violated the obligations, prohibited acts, and preventive measures during the emergency quarantine period.

In mid-July, when a North Korean defector illegally crossed the DMZ and returned to North Korea’s Kaesong again, the North Korean government blocked the entire Kaesong area and declared a “maximum emergency system” in accordance with the revised Infectious Disease Prevention Act. This seems to have been a Special level (Level 2) measure, and the attack on Korean sailors crossing the border on the west sea on September 24 seems to be related to the provisions of this Act.

August-September was also a period when the DPRK was damaged several times by typhoons and floods. Because of infectious diseases such as typhoid, cholera, and other infectious diseases that occur during summer floods, the DPRK’s Covid-19 response was implemented along with measures for other infectious diseases.

Phase 3: Management Phase through Intensive Examination: End of September 2020-Present

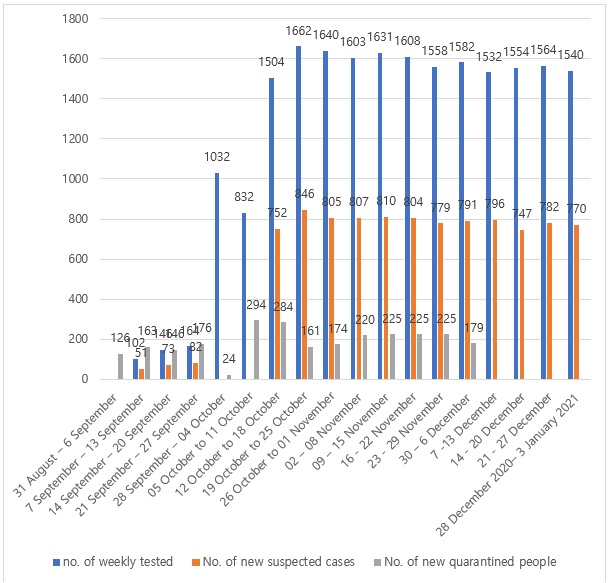

The end of September 2020 marked the beginning of a new phase of management of the Covid-19 pandemic in the DPRK. A considerable number of Covid-19 tests had been conducted and statistics based on these tests began to be released.

The inflow of Covid-19 kits to the DPRK from China, Russia, and the International Red Cross had begun at the end of February, but it seemed the number secured were less than needed. Mass testing began from the end of September with the introduction of a large-scale test kit and a PCR machine. The Covid-19 situation in the DPRK was henceforth featured in the weekly status report of the WHO South East Asia Regional Office.

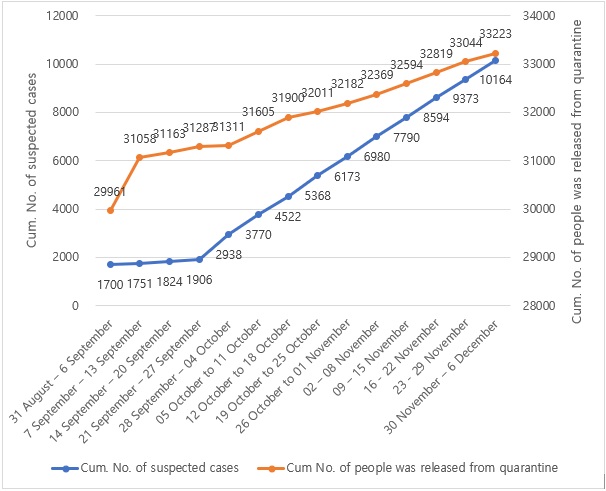

The number of weekly tested cases was only 100-170 until mid-September. From then on, 800-1700 tests per week were reported. The DPRK initially defined the number of suspected patients as those with severe acute respiratory infections (SARI), but from the end of September, it appears to have based its announced case numbers on test results. The number of weekly new suspected cases increased significantly from mid-October to 700-800 cases per week. It remained at the level of 700-800 cases until the end of December. The DPRK reported that 33,044 persons had been released from quarantine by November 26. As the DPRK government continues to claim that no Covid-19 cases occurred, the number of suspected patients officially announced contributes to estimates of the current state of the Covid-19 outbreak in North Korea.

Source: South-East Asia Region WHO – Weekly Situation Reports.

Figure 2. Number of weekly tested, number of new suspected cases, and number of new quarantined people of the DPRK.

Source: South-East Asia Region WHO – Weekly Situation Reports

Figure 3. Cumulative number of suspected cases and cumulative number of people released from quarantine in the DPRK.

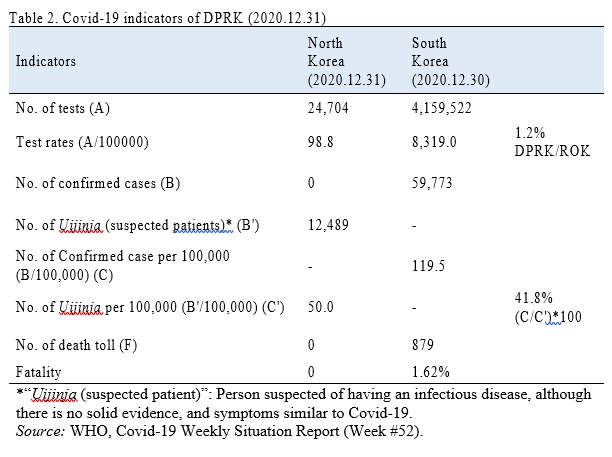

The following is a comparison of the North Korean Covid-19 epidemic and response status reported by the DPRK to the WHO South East Regional Office (SEARO) with those of the ROK until the end of November 2020.

The number tested in the DPRK was 98.8 per 100,000 people compared to 1.2% in the ROK. As of December 2020, the DPRK reported that there is no officially confirmed case, but the number of suspected patients is reported as 12,489, or 50.0 for every 100,000 people, compared to 41.8% of the 119.5 confirmed cases per 100,000 people in the ROK.

Despite these stable figures, the DPRK raised the level of emergency quarantine to Super-Special Level (Level 3) on December 2, 2020. This shift appears to be the result of more Covid-19 patients in the winter as expected.

Characteristics and Evaluation of the DPRK’s COVID-19 Response

Below is a summary of the current situation and characteristics of DPRK’s Covid-19 response.

- The Covid-19 epidemic was regarded as a highly important issue, which led to an active and strict response.

Although the containment measures have caused significant economic losses, the DPRK has implemented measures such as long-term border closure, and the incubation period and quarantine period have operated for 30-40 days,[5] which is twice as long as the generally adopted two weeks. It is also the only major SEARO country to continuously block inter-regional movement.

- Covid-19 seemed to be under control until mid-December 2020.

The North Korean government officially insists that no patients have been confirmed as infected with coronavirus, but that claim raises many questions. Above all, skepticism arises from the fact that the first Covid-19 patient occurred in China in early December 2019, and the DPRK did not close until January 25, 2020, leaving a two-month period for the virus to cross the border. Some sources have reported that a number of Covid-19 patients and deaths have occurred.[6] However, those who say there are no Covid-19 patients and those who say there are many provide insufficient evidence to prove their assertion.

Nevertheless, to date, the Covid-19 outbreak in the DPRK has not caused a large-scale disaster situation and seems to be managed by tough measures at considerable cost to the economy. The important basis for such judgment is that, although participation was reduced from the original plan, the highest powers, including Chairman Kim Jong-un, attended major political events such as the Supreme People’s Assembly (March 11, 2020) and the 75th anniversary celebration of the Party’s establishment (October 1, 2020) without wearing a mask. In particular, at the 6th Memorial Meeting for Old Veterans attended by many senior veterans, the highest risk group for Covid-19, Chairman Kim Jong-un gave a long speech without a mask. In addition, schools opened partially in April and fully in June 2020.

The Covid-19 outbreak was managed in the early days of the outbreak, to some extent in the absence of securing diagnostic kits and protective equipment, because the existing emergency quarantine system in the DPRK works to some extent effectively. However, a separate discussion is needed on the appropriateness of the DPRK’s response method for the Covid-19 epidemic from the perspective of human rights and the problems that will arise when the Covid-19 epidemic is prolonged.

- Difficulties in the economy and livelihood are increasing as the Covid-19 pandemic is prolonged.

Strict international and US economic sanctions, natural disasters, and the Covid-19 outbreak are causing “Samjoong-go (triple whammy)” impacts in the DPRK, which is increasing the difficulties in the North Korean economy and peoples’ lives.

The national economy and peoples’ lives were maintained to some extent until the end of December 2020 through the procurement of goods through the market, the use of national stockpiles, the conversion of export goods to domestic demand, and food supplies from China and Russia. Recently, however, imports and exports with China have declined dramatically. According to data from the International Trade Commission (ITC), the DPRK’s trade volume between January and September 2020 decreased to 87% compared to the same period in 2016. Imports from China also decreased by 73%.

Also, according to the Ministry of Unification, the number of North Korean defectors in the second quarter of 2020 decreased by 96% compared to the same period in 2019. This drop seems to be due not only to the strengthening of the DPRK’s border crackdown, but also to China’s border crackdown to prevent from influx of Covid-19 from the DPRK. This decrease in the number of defectors indirectly shows the difficulty of smuggling and exporting between the DPRK and China. This difficulty in smuggling between the DPRK and China was not experienced even during the North Korean famine in the late 1990s. Some experts are warning, therefore, that if the situation fails to improve until the springtime of March and April 2021, a large-scale disaster may recur similar to the end of the 1990s.[7]

Evaluation of North Korea’s Covid-19 Response

Despite external circumstances, such as economic sanctions, and internal difficulties, such as a lack of testing kits and personal protective equipment, the extreme situation caused by Covid-19 is not worsening, at least not rapidly. Some experts even argue that the DPRK is an example of responding appropriately to Covid-19 in countries with limited resources. These positive results seem to be produced by the DPRK’s strongly centralized state and systematic anti-epidemic structure, active and prompt decision-making such as border closure, strict enforcement, and systematic and extensive propaganda activities. Nevertheless, the DPRK’s response to Covid-19 faces problems due to limited diagnostic capabilities and difficulties in securing appropriate quarantine facilities, protective equipment, and treatment facilities. In addition, it is expected to face difficulties in obtaining vaccines in the short to medium term.

These problems are a common phenomenon not only in the DPRK, but also in other low- and middle-income countries. In the case of the DPRK, however, there is an additional problem. As mentioned above, even humanitarian aid is struggling to reach the country due to strong economic sanctions. In addition, the DPRK is currently proceeding with limited international cooperation. Accordingly, problems exist in the transparency of Covid-19 related data and the sharing of real-time professional information.

Covid-19 is a novel coronavirus, and its exact epidemiological characteristics are still emerging. Moreover, recently, variants of Covid-19 have been continuously occurring. It is imperative, therefore, to monitor the situations in different parts of the world in real time and share each other’s experiences.

The DPRK exchanges some information with China and international organizations residing in Pyongyang. Rodong Shinmun (a DPRK major newspaper) reported the news of the global Covid-19 epidemic to DPRK readers and guidelines of the WHO, and it reported publicly that the DPRK is working with the WHO in particular. Nevertheless, there is a limit to systematically collecting and analyzing professional and vast information in real time. This shortfall arises because most of the information related to Covid-19 is technical and specialized, so it is not enough to exchange information between policy makers or ordinary diplomatic officials. Most of all, the channels with neighbors who speak the same language—that is, with South Korean experts—are blocked.

Diagnostic equipment, treatment facilities, and vaccines are expensive, but regular information exchange by experts on infectious disease epidemics does not require a special budget and is possible to implement with only political decisions. Not only do the two Koreas share a border. They speak the same language, and Korea is now a country with Covid-19 expertise based not only on the ROK experience but also all over the world. In September 2018, the two Koreas publicly promised to exchange information on infectious diseases and cooperate in an agreement between the leaders of the two Koreas. Two working-level talks were held in November and December 2018 with information exchanged related to influenza. During Covid-19, it is problematic that the DPRK is still not responding to a dialogue proposal between the ROK government’s experts on infectious diseases.

To significantly improve DPRK’s ability to cope with pandemics, it must expand quarantine capacity, treatment supplies, and related facilities in a short time. This goal is impossible to achieve without cooperation from the international community, China, and the ROK. In addition, it is necessary to establish a stable crisis response system in which real-time information is transparently disclosed and exchanged with global experts, including Korea.

The Future Prospects and Policy Tasks by Major Actors

For North Korean society to effectively respond to the prolonged Covid-19 pandemic, more active efforts by the North Korean authorities are needed. The pandemic cannot be solved by one country alone. Therefore, the role of the international community including both Koreas is also critical. Future prospects and policy tasks by major actors are listed below.

What is important to the prospects of the North Korean health care sector in 2021 are the prolonged Covid-19 epidemic, the establishment of new US-DPRK relations in a Biden administration, and the direction and contents of the Five-Year National Economic Development Plan at the 8th Worker’s Party Congress in January 2021. The tasks related to the prolonged Covid-19 epidemic in each dimension are summarized below.

a. Maintaining stable management of the Covid-19 epidemic

At the 8th Congress of the Workers’ Party of DPRK in January 2021, there was no special announcement from the health care sector except for the re-declaration of the superiority of socialist health care.

So long as the Covid-19 epidemic continues, the DPRK should place high priority on securing sufficient food, diagnostic and protective equipment, and treatment facilities necessary for its Covid-19 response. Doing so will be impossible under strong economic sanctions of the United States and the international community. Thus, the DPRK’s first step is to establish a more open and cooperative relationship with the international community, including the ROK.

As the Covid-19 epidemic prolongs into 2021, continuous response and management seem inevitable. Therefore, the existing DPRK management system centered on movement restrictions, quarantine, and selection is expected to continue.

Obtaining a reliable supply of vaccines and treatments is likely to emerge as a new issue for the DPRK for which it is ill-prepared. Regarding vaccines, the DPRK has already taken steps to secure a minimum vaccine at low cost through an application through the COVAX facility.[8] The COVAX facility aims to jointly secure and supply vaccines to at least 20% of the population by the end of 2021, even in poor countries. Fortunately, the DPRK also participated in this association. The problem, however, is that supply is dominated by commercial multinational pharmaceutical companies, backed by the United States, the European Union, and Japan, committed primarily to vaccine nationalism.

Recently, pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer, BioNTech, and Modena announced promising results of vaccine clinical trials, raising the expectations of many, but wealthy countries such as the United States have already acquired the expected vaccine production next year. The United States even refused to participate in the non-profit global COVAX consortium, but only after securing vaccine for its own people, did incoming President Joseph Biden, order participation. In addition, for-profit pharmaceutical companies are looking for opportunities to benefit greatly from this oligopolistic position by raising the price of the vaccine. Under these circumstances, skepticism has arisen that low- and middle-income countries can obtain the vaccine in a short timeframe. Even if a supply is secured, it will be unlikely that vaccination will have a population-wide effect if only 20% of the population is inoculated. Fortunately, the DPRK can expect China’s cooperation in terms of vaccine supply. But China, too, will prioritize vaccinations for its own citizens, making it unlikely that the DPRK can secure enough vaccines in 2021 to overcome the pandemic’s grip. In addition, it is likely to face difficulties in securing related financial resources for the requisite infrastructure. It is highly likely, therefore, that the DPRK will have to seek help from allies such as China, Russia, the WHO, UNICEF, the Red Cross, and the ROK.

b. Increasing need to strengthen quarantine for resumption of international trade and tourism

Currently, the DPRK’s top state management goal is “Jaryek-Boogang” (self-prosperity). This goal is expected to become even more important in 2021. For this goal to be realistic, it is necessary to lift some, if not all, economic sanctions on the DPRK imposed by the United Nations and the United States. On the realistic assumption that severe economic sanctions will continue for a considerable period, however, there are measures the DPRK can take to ease or withdraw the border closures and to operate more active trade in goods and services such as tourism. In principle, tourism is not subject to economic sanctions, but tourists are unlikely to come amid Covid-19 uncertainty. To activate a more active goods trade and tourism industry through easing or withdrawing border closures, it is necessary to establish an even stronger quarantine and quarantine system (including facilities, equipment, manpower, etc.) and to establish a stronger and more specialized international cooperation system with neighboring countries. To this end, it is expected that China and Russia will be the first to actively contact and request cooperation. If stable tourism exchange between the DPRK and China becomes possible, a dialogue channel with neighboring countries including the ROK and Japan could also open.

c. Improvement of inter-Korean relations and expansion of exchanges

It is fortunate that at the 8th Congress of the Workers’ Party of DPRK, there were no extreme criticisms against the ROK as before, and that DPRK opened up the possibility of conditional dialogue with ROK.[9]

First and foremost, If the DPRK wants peace on the Korean Peninsula as declared at the bilateral summit, the DPRK needs to change its hostile attitude toward the ROK government, which the DPRK expressed by destroying the inter-Korean liaison office on June 17, 2020. Second, exchanges with the existing ROK non-governmental organizations for cooperation with the DPRK must be proactively resumed. The ROK is not only one of the major players surrounding the Korean Peninsula, but it also can orchestrate wider efforts to realize cooperation by many parties in the East Asia region and beyond with the DPRK. In addition, because the DMZ is a common border between the ROK and the DPRK, it is difficult to resolve common infectious diseases such as malaria, bird flu, African swine fever, and forest diseases without cooperation between the two Koreas. A similar logic applies to the DPRK-Russian-Chinese cooperation regarding viral transmission in their shared borders—especially in the Tumen wetlands—a major transmission location for Avian viruses in the East Asian bird flyway.

d. Expanding transparency and accuracy of information related to Covid-19 and international exchange

If information is not transparent and individual citizens and families lose confidence in the government’s Covid-19 announcements, action on the outbreak is likely to be ineffective. Therefore, rather than obsessing with the declaration that there are no Covid-19 patients because this might be used by external adversaries as a weakness to exploit, the DPRK government should secure a system that enables rapid and rational response by creating a more detailed and accurate real-time surveillance system, publishing statistics, and actively exchanging professional information internationally.

At present, the ROK is struggling to strike a balance between the United States, its traditional ally, and China, an economically important partner, despite being a party to the Korean conflict. The recent conflict over the deployment of THAAD by the US military showed the ROK’s difficulties.

The ROK’s Moon Jae-in administration hopes to resume exchanges with the DPRK. First, it has proposed several times to reconnect the inter-Korean communication lines that have been discontinued since the end of January 2020 and to cooperate on quarantine issues such as Covid-19, African swine fever, and malaria. In particular, the exchange of information on infectious diseases and mutual cooperation were already agreed upon at the inter-Korean summit in 2019. The ROK’s President Moon has repeatedly requested the restoration of the cooperative relationship using the expression “South and North Korea are one living community,” but the DPRK did not answer. Moon proposed again the establishment of the Northeast Asia Quarantine and Health Cooperation Organization (NAQHC) including the ROK, the DPRK, China, Japan, and Mongolia.

President Moon Jae-in delivered a keynote speech at the 75th General Assembly General Discussion held at the United Nations General Assembly on September 22, 2020 (New York Time, USA). Parts of the speech are highlighted below:

Now, it is difficult to take responsibility for all inclusive security with one nation’s capabilities alone. Cross-border cooperation is necessary to protect the peace of one country and the life of one person, and a multilateral security system must be established.

Until now, I have been talking about a ‘peace economy’ that helps both South and North Koreans live well together. It has also emphasized cooperation between the two Koreas in the field of disaster and disaster and health care. Today, I hope that the issues on the Korean Peninsula after Covid-19 will also be considered from the perspective of international cooperation that has strengthened inclusion, and I propose a ‘Northeast Asia Quarantine and Health Cooperation Organization’ in which China, Japan, Mongolia, and South Korea, including North Korea, participate together. A partnership in which various countries protect lives and guarantee safety will serve as the foundation for North Korea to secure security through multilateral cooperation with the international community.

President Moon Jae-in’s speech to the United Nations is not long, but in a Covid-19 pandemic situation, it has many important implications beyond US-DPRK relations.

First, international cooperation is essential. Germs have no borders. Malaria bird flu and African swine fever cannot be resolved alone. Cooperation with bordering neighboring countries is crucial. President Moon Jae-in’s proposal for the NAQHC, including the ROK, the DPRK, China, and Mongolia was a bit late, but it is an indispensable approach. Second, the current Covid-19 pandemic has shown that economic growth is impossible without establishing a strong public health system. Moon Jae-in also proposed an economic belt in the transboundary region of the West Sea and the East Sea for peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula. However, on September 21, 2020, when President Moon was giving a speech to the United Nations, a South Korean who crossed the border in the West sea was attacked by North Korean soldiers. This incident yet again raised tensions between the two Koreas and sharply demonstrated the volatility of the military standoff between the two Koreas, including the West Sea beyond the DMZ on land. This event showed that the West Sea could be a space of peace and prosperity or of war and destruction. Koreans must choose.

Finally, the DPRK—and indeed, all states—must embrace a shift in their national security paradigms. The Covid-19 pandemic confirmed that public health problems seriously harm human survival. In the future, public health is at the center, not the margins of national security. This shift means that the world needs to switch from ‘hostile’ security to ‘mutually cooperative’ security.

The DPRK has yet to express positive intentions for renewed inter-Korean exchanges. This silence is likely the result of disappointment in the South Korean government due to the failure of the 2019 Hanoi Summit, but it is also because the DPRK does not believe in the capabilities of the ROK government to render assistance because of sanctions.

This doubt arose from an incident shortly before the Hanoi talks when the United Nations Command (UNC) banned the delivery of Tamiflu, which the ROK was trying to send to the DPRK, because trucks could not be used (In fact, this was beyond UNC’s authority).[10] The DPRK saw the United States behind this blockage, and it also observed that unless the United States approved, the ROK government did not have the ability to send medicines to the DPRK, even ones that were not subject to economic sanctions. The DPRK views trying to cooperate with the ROK government to be a waste of time, therefore, because the ROK cannot keep promises between North and South Korean leaders.

To break distrust between the DPRK and the ROK, rather than repeated expressions of cooperation, it is necessary either to persuade the United States that the ROK may undertake such cooperation or show that it will proceed despite US objections. Below are important tasks the ROK must take to demonstrate such tangible ability.

First, for humanitarian exchange and cooperation, the ROK government needs to make an independent decision.

Despite the special characteristics of the two Koreas, the current method of obtaining permission from the United Nations for all humanitarian aid is making meaningful and peaceful humanitarian exchanges between the two Koreas difficult. For humanitarian exchange and cooperation with the DPRK, the ROK government needs to make an independent decision or to obtain comprehensive approval from the United Nations.

Second, it is necessary to accelerate the establishment of the NAQHC.

Not only Covid-19, but also swine flu, bird flu, African swine fever, malaria, forest pests, and air pollution are not unique to the two Koreas, and a solution must be sought with neighboring China and Japan. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a multilateral Northeast Asian quarantine network including China, Japan, and Mongolia, which integrates and expands on the existing inter-Korean quarantine cooperation structure. For this purpose, the ROK government should first persuade the governments of China, Japan, and Mongolia to establish a cooperative network and allow the DPRK to enter within this multilateral structure. Soon, cooperation between these countries will be inevitable for North Korea to secure a Covid-19 vaccine, so the ROK should use this as an opportunity to resume inter-Korean dialogue.

Once the NAQHC is established and active, it may expand its scope to encompass all Asian countries and gradually expand the target issues to include children’s health, reproductive health, and environmental issues, including infectious diseases. In this process, it is necessary to consider the creation and operation of a fund called Asia Children’s Fund (ACEF) like the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Third, it is necessary to implement the North Korean exchange project with the COVAX facility and other international organizations and to strengthen the ROK government’s initiative in the process.

Inter-Korean exchanges and cooperation have frequently been implemented and disconnected according to changes in the political situation. In this way, it is difficult for exchange and cooperation to produce results. To overcome these problems, the ROK government should more actively try to promote health projects on the Korean Peninsula through international organizations and find a way to secure financial and technical resources. In addition to vaccines, drugs, protective equipment, and diagnostic equipment necessary to cope with the Covid-19 epidemic, basic food and energy, general fluids or antibiotics, materials necessary for pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn child rearing, and basic vaccinations should be provided first.

Fourth, for the ROK government to restore relations with the DPRK government, it is important to fulfill its existing promises.

The ROK government suspended tours to Mount Geumgang and eventually withdrew from the Kaesong Industrial Complex due to the DPRK’s shooting of tourists at Mount Geumgang and the sinking of a South Korean warship in the West Sea. There was a reason for the ROK to take its own actions in response to the DPRK’s provocations, but it also did not fulfill the promise it made with the DPRK regarding the Kaesong Industrial Complex. Therefore, to resume inter-Korean exchanges and cooperation, such as quarantine cooperation, it will be necessary to first resume the tasks promised by the two Koreas.

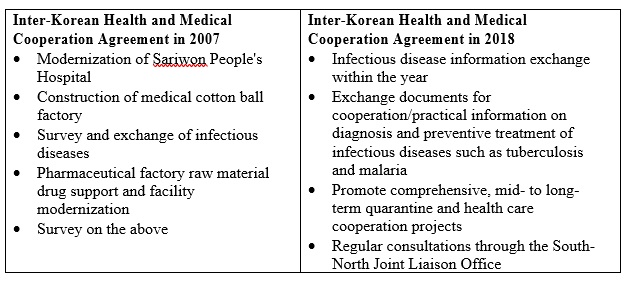

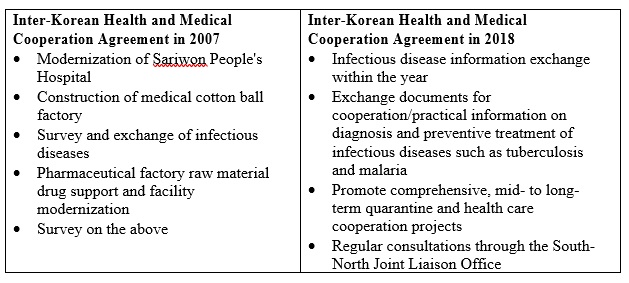

The two Koreas made a mutual promise but failed to implement the operation of the Kaesong Industrial Complex and Mount Kumgang and Kaesong tourism projects. In the health care sector, there were maternal and child health programs, children’s measles and rubella vaccination projects, and inter-Korean agreements in 2007 and 2018.

At the 8th Congress of the Workers’ Party, Kim Jong un also announced that the implementation of the previous promise was a prerequisite for the recovery of inter-Korean relations. Due to the Covid-19 epidemic, it will not be easy to resume tourism on Mount Geumgang or restart the Kaesong Industrial Complex right away. Even when the Covid-19 epidemic ends, it will take time to reactivate these projects. Therefore, preliminary work to prepare for exchange and cooperation after Covid-19 should be started immediately rather than being placed at the back of the queue.

Fifth, it should lead to the conclusion of the South-North Health Agreement.

In the event of joint response and cooperation between the ROK and the DPRK against infectious diseases such as Covid-19 becomes realistic, the South and North Korean health care agreements must be signed to prevent such cooperation from becoming temporary. In the past unification process of East and West Germany, for example, the first cooperative activity made before unification was their health agreement.

The two Koreas are committed to agreements that have already been reached, such as the 1st Inter-Korean Prime Ministers’ Meeting, the 1st Agreement of the Inter-Korean Economic Cooperation Joint Committee, and the 1st Agreement of the Inter-Korean Health and Medical and Environmental Protection Cooperation Subcommittee. As a result, it is necessary to develop a more advanced inter-Korean health care agreement.

The DPRK and the ROK should develop a more advanced Inter-Korean Health and Medical Agreement based on the contents already reached in the above agreements. The following content should be included.

China

Peace and prosperity between the ROK and the DPRK are important to prevent the Korean Peninsula from becoming a front line of conflict between China and the United States. If China raises the level of involvement in the DPRK, the United States in the ROK will try to implement a more aggressive policy toward China, such as deploying THAAD and expanding military training in Korea, the United States, and Japan. Therefore, China should strengthen its mediating role in exchange and cooperation between the ROK and the DPRK. It is necessary to participate in the establishment of the NAQHC recently proposed by President Moon Jae-in and play a more active role in compelling the DPRK to participate in it.

The US policy toward the DPRK, including the former Trump and Obama administrations, centered on economic sanctions. The DPRK has become a nuclear-armed state as a result of the adherence to these policies over the past decade. But perhaps even more important is that the DPRK’s dependence on China continues to grow. As US economic sanctions intensify, China will have the power to control the life and death of the DPRK. The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic is accelerating this pattern.

If economic sanctions, natural disasters, and the “three middle highs” created by Covid-19 are prolonged, and political, economic, and social difficulties and turmoil in the DPRK are driven to extremes, the only option for the DPRK is increased dependence on China. This is not what the DPRK wants, and it is also undesirable for the ROK and the United States. China, too, will not allow the DPRK to fall under the influence of the United States or South Korean.

Since the inauguration of President Joe Biden, the United States has sought a new principle of approaching North Korea. The US policy toward the DPRK should take a different approach from the Obama administration and the Trump administration. To reduce the DPRK’s dependence on China in politics, economics, and society, it is necessary to (1) move away from enmity and to provide conditions for the DPRK’s own strength and (2) help promote economic exchanges between the ROK and the DPRK. To achieve the first, economic sanctions should be eased and ultimately withdrawn. For the second, the existing dialogue-centered policy on the Korean peninsula between North Korea and United States should shift to increase the authority and autonomy of the DPRK. In this context, the current Covid-19 pandemic could provide an important stimulus.

International Organizations and Global Civil Society

Currently, the DPRK is not the only country that is struggling with Covid-19. The pandemic, which has hit the world since early 2020, has caused nearly 100 million confirmed cases and over 2 million deaths. The greatest lesson brought by the Covid-19 pandemic is that all humans are closely connected and, as WHO Secretary-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said, no one can be healthy unless all are healthy. In that sense, it is necessary to overcome the human disaster brought by Covid-19 in close solidarity with all humankind.

The leaders of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) held on the 20th of last month adopted the following Kuala Lumpur Declaration. “We need to cooperate in diagnostic testing, development, production, manufacturing and distribution of essential medical supplies and services, and equitable access to medical measures such as vaccines should be made smoothly.”

In addition, the COVAX facility has begun to distribute vaccines with the aim of distributing Covid-19 vaccines sufficiently and fairly to all countries. Unfortunately, the COVAX facility’s efforts to provide vaccines to poor countries are unlikely to be realized within the timeframe originally planned because of wealthy countries prioritizing their interests. The DPRK will face great difficulty in securing sufficient vaccines. In that sense, the international community now needs measures based on stronger solidarity principles. Above all, for the COVAX facility to work, the powers must actively participate in this global project, without which, their own vaccination programs may ultimately be in vain.

Going further, international organizations and civil societies of the world work must together tell the powers that (1) all countries stop war during the Covid-19 pandemic, (2) rich countries stop demanding debt repayment from poor countries, and (3) all economic sanctions should be called to be temporarily suspended.[11]

The DPRK is struggling amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Amid strong economic sanctions and natural disasters, the DPRK is confronting the pandemic with strong measures such as long-term border closure. As a result, there is a constant food shortage. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) redesignated the DPRK as a food shortage country in a report on the “Crop Prospect and Food Situation” for the first quarter of 2020 released in March. According to the “Food Security and Nutrition in Asia-Pacific” jointly announced by the UN-affiliated Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Food Program (WFP), and UNICEF on the 20th (local time), 47.6% of North Koreans were suffering from malnutrition. This figure is the highest among 30 countries surveyed in Asia and the Pacific during the same period.[12]

Jerry Nelson, an emeritus professor at the University of Missouri in the United States, told Radio Free Asia (RFA) that “about 60% of the total North Korean population is unable to consume 2,100 calories per day due to Covid-19.” In June, the DPRK received 800,000 tons of food (600,000 tons of rice and 200,000 tons of corn) from China and 25,000 tons of wheat from Russia, but this alone is not sufficient.

As mentioned above, until mid-December, the DPRK has maintained the Covid-19 pandemic under some level of control, but it is difficult to sustain. Some experts worry that if this situation continues through March or April 2021, it may lead to tragedies beyond the famine, which starved to death about 300,000 people in the late 1990.

Economic sanctions by the United Nations and the United States stipulate that humanitarian aid should not be threatened and humanitarian aid of North Koreans should not be threatened. But in reality, humanitarian aid is difficult for many reasons, including:

- Many people are halting economic assistance for humanitarian projects.

- They are unable to find a ship to carry goods to the DPRK.

- There are many cases where it is not possible to obtain necessary goods because they are unable to pay through credit cards or banks.

- It is uncommon for humanitarian goods to be brought in due to strengthened border screening.

- Banking transactions are prohibited, and humanitarian activists are taking risks and passing through China with cash. Sometimes they are detained and punished for violating China’s foreign exchange law (persons cannot bring more than $10,000). Even that, however, is impossible due to the Covid-19 outbreak.

- Americans who have been involved in long-term humanitarian aid activities toward the DPRK are banned from visiting the DPRK and are in a situation where medicines that must be continuously supported are cut off. Allowing a small number of humanitarian aid and visits is nothing but a show-off.

Despite this situation, Chairman Kim Jong-un said on August 14, “We will not allow outside help in the situation of quarantine against the new Covid-19 virus infection (Covid-19).” Due to this, excluding China, Russia, and some international organizations, there is little international exchange.

The DPRK is voicing “No Problem” despite the economic sanctions of the United States and the United Nations. The United States also argues that US-led international sanctions are not the cause of humanitarian disasters in the DPRK. This “No Problem” collusion pattern can invite dangerous consequences, which not only distorts the facts but can also lead to many victims, making intervention difficult by missing confirmation timing for catastrophic situations such as famine. This is similar to the “No Problem” collusion pattern in the North Korean famine of the late 1990s.

A total of 229 North Korean defectors entered the ROK in 2020, a 78.1% decrease from 2019. It is interpreted that the route of defection was blocked due to the worldwide cause of Covid-19.[13] This not only shows the difficulty of North Korea, but also the difficulty of the informal North Korea-China trade that is important to the North Korean economy. In addition, the US CNN broadcast cited the announcement of China’s customs authorities that China’s exports to North Korea in October were $253,000 (KRW 280 million), down 99% from the previous year. During the same period, China’s imports from North Korea also decreased by 74%. These levels were not reached during the North Korean famine in the late 1990s.

If the DPRK’s response to Covid-19 in the future and its consequences depend on whether the outbreak is prolonged, the other most important variable is support from China. In fact, it was reported on April 26 that the Chinese Communist Party dispatched about 50 medical experts to the DPRK from the People’s Liberation Army General Assembly (301 Hospital) in Beijing in April 2020. In addition, it has provided support for inspection equipment and food. Above all, the DPRK shares an extensive border with China, and the degree of closure of that border will have an absolute impact on the DPRK’s economy. If the current situation is prolonged, the DPRK’s dependence on China will increase.

The DPRK needs to establish a more open cooperation system with the international community including the ROK and the United States. The United States also needs to make sure that the DPRK is not in extreme situations or makes its worst choices. To this end, it is necessary to change the policy on the Korean Peninsula that the Obama and Trump administrations took in the past, and the core of this is to proceed with step-by-step denuclearization while opening the possibility of peace and prosperity through the vitalization of exchanges between the two Koreas.

Finally, and most importantly, the greatest tragedy for the DPRK now and in the future are the serious economic crises, including food shortages, rather than the Covid-19 pandemic itself. It should not be forgotten that, not only the two Koreas, but also the international community, must do everything possible to prevent such a tragedy.

III. ENDNOTES

[1]Ri is the local or village-level administrative unit in the DPRK.

[2]“An epidemic may be restricted to one location; however, if it spreads to other countries or continents and affects a substantial number of people, it may be termed a pandemic.” C.J. Nicholas Mascie-Taylor and Kazuhiko Moji, “PANDEMICS”, NAPSNet Special Reports, October 12, 2020, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/pandemics/

[3] Here, quarantine workers measure passengers’ body temperature and check whether they have a permit to move.

[4] South Koreans use special masks (KF94), which can prevent ultra-fine aerosols.

[5] In a situation where test kits are extremely scarce, the period of quarantine is inevitably extended.

[6] The Sankei News, 2000. Apr. 26.

[7] Of course, as the food situation in North Korea worsens, the situation will change if large-scale emergency food aid is provided in China or Russia.

[8] The COVAX facility is promoted by the WHO, the Infectious Disease Innovation Association (CEPI, vaccine development), and the World Vaccine Immunity Association (GAVI, vaccine supply) with the goal of equally supplying vaccines to 20% of the population by the end of 2021. It is a multinational coalition; it reserves a certain amount of vaccine for provision at low cost to underdeveloped countries.

[9] North Korea demanded that South Korea stop allied military exercises with USA and keep its promises at the existing summit.

[10] Lee, J. Y. and J. Kim (2019). International Cooperation to Build a Peace Regime on the Korean Peninsula. Seoul, Korean Institute for National Unification (KINU).

[11] Shin, Young-jeon. (2020). DPRK sanctions and inter-Korean health cooperation during the Covid-19 pandemic. Civil Peace Forum, Seoul, People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy.

[12] WFP, FAO, UNICEF and WHO (2021). Asia and the Pacific Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2020.

[13] Ministry of Unification, ROK, 2021.

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.