by Desmond Ball, Bill Robinson, Richard Tanter, and Philip Dorling

25 June 2015

The full PDF version of this report is available here

I. Introduction

The Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap, located just outside the town of Alice Springs in Central Australia and managed by the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), is one of the largest U.S. technical intelligence collection facilities in the world. The corporate presence at Pine Gap has expanded substantially in terms of both the number of companies involved and the total number of civilian contract personnel, and has changed significantly in functional terms, since the 1990s. It includes some of the major US aerospace and defence companies, such as Raytheon, Boeing, Northrop Grumman and General Dynamics, as well as major computer companies, such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard. It also includes an increasing number of ‘pure play’ companies, who focus almost entirely on contracts from the National Reconnaissance Office, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and National Security Agency (NSA), such as Scitor Corporation, SAIC and Leidos.

In addition to the supply of equipment (such as satellite dishes/radomes and computers) and the provision of specialised technical services (such as satellite control and antenna alignment), these companies are now also engaged in a wide variety of management, operations and maintenance roles. While the base is nominally a ‘joint’ United States-Australian facility, virtually all of the major companies involved are U.S. corporations or their Australian branches – further emphasizing the already heavily asymmetrical character of the ‘jointness’ of Pine Gap. Moreover, corporations are not necessarily the best or most objective interpreters of US-Australian security and intelligence priorities or Australia’s national interests.

Authors

Desmond Ball is Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University (ANU). He was a Special Professor at the ANU’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre from 1987 to 2013, and he served as Head of the Centre from 1984 to 1991.

Philip Dorling is a Visiting Fellow in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of New South Wales, Canberra, at the Australian Defence Force Academy.

Bill Robinson writes the blog Lux Ex Umbra, which focuses on Canadian signals intelligence activities. He has been an active student of signals intelligence matters since the mid-1980s, and from 1986 to 2001 was on the staff of the Canadian peace research organization Project Ploughshares.

Richard Tanter is Senior Research Associate at the Nautilus Institute and Honorary Professor in the School of Political and Social Sciences at the University of Melbourne.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Special Report by Desmond Ball, Bill Robinson, Richard Tanter, and Philip Dorling

The corporatisation of Pine Gap

The Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap, located just outside the town of Alice Springs in Central Australia and managed by the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), is one of the largest U.S. technical intelligence collection facilities in the world. The 60 hectare operations area of Pine Gap today houses three distinct functions and operational systems. Its original and still principal purpose is to serve as the ground control station for geosynchronous signals intelligence (SIGINT) satellites developed by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); it probably remains the CIA’s most important technical intelligence collection station in the world. There are now 38 satellite dishes/radomes at Pine Gap. Most are still concerned with the core function of controlling geosynchronous SIGINT satellites and processing and analysing the intercepted intelligence.

Secondly, since late 1999 Pine Gap has hosted a Relay Ground Station (RGS), which relays data from U.S. missile launch detection/early warning satellites/Overhead Persistent Infrared (OPIR) – formerly the Defense Support Program (DSP) but now including the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS) – to both U.S. and Australian HQs and command centres. Six of the satellite terminals at Pine Gap (four in radomes and two unshielded) belong to the RGS. Another three radomes are probably associated with the U.S. Missile Defense Agency’s Space Tracking and Surveillance System (STSS).

Finally, Pine Gap appears to have acquired a FORNSAT/COMSAT (foreign satellite/ communications satellite) interception function in the early 2000s. This was probably presaged with the arrival of Service Cryptological Agency (SCA) elements at the end of the 1990s. Two 23-metre dishes suitable for COMSAT SIGINT Development (Sigdev) were installed inside 30-metre radomes in 1999-2000. A Torus multi-beam antenna was installed at Pine Gap in 2008.[1]

The corporate presence at Pine Gap has expanded substantially in terms of both the number of companies involved and the total number of civilian contract personnel, and has changed significantly in functional terms, since the 1990s. 70 per cent of the Pine Gap facility’s approximately 800 personnel have been U.S. and Australian citizens employed by private companies since at least 2008 (Table 1).[2] However the numbers of Australian staff, either government and contractor, had declined by 2015. In 2008 29 per cent of Pine Gap personnel were employees of US contractors while 41 per cent were employees of Australian companies (presumably including sub-contractors to US contractors). In that year 18 per cent of the personnel at the facility were US Government employees, and only 12 per cent were Australian Government staff.

Seven years later in 2015, while the overall proportion of contract staff remained at 70% of approximately 800 staff, the balance of U.S. and Australian staff had shifted in both the government and corporate groups, with the proportion of Australian government and corporate employees declining to just 10% and 40% respectively.

Table 1. Pine Gap personnel (approx.) 2008 – 2015

| Year | Total number | Australian government employees | U.S. government employees | Australian contractors | U.S. contractors |

| 2008 | 800 | 12% | 18% | 41% | 29% |

| 2015 | 800 | 10% | 20% | 40% | 30% |

Sources: ‘Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap’, Hansard (House of Representatives), 14 May 2008, p. 5030; and information provided by the Australian Department of Defence, 18 June 2015.

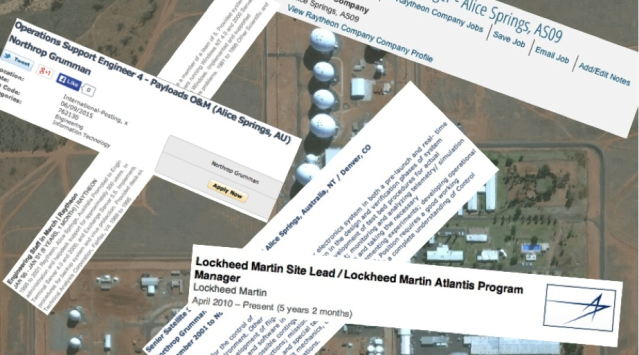

Contractors at Pine Gap include some of the major US aerospace and defence companies, such as Raytheon, Boeing, Northrop Grumman and General Dynamics, as well as major computer companies, such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard. It also includes an increasing number of ‘pure play’ companies, who focus almost entirely on contracts from the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and National Security Agency (NSA), such as Scitor Corporation, SAIC and Leidos.[3] In addition to the supply of equipment (such as satellite dishes/radomes and computers) and the provision of specialised technical services (such as satellite control and antenna alignment), these companies are now also engaged in a wide variety of management, operations and maintenance roles.

The corporatisation of Pine Gap parallels the wider trend in the U.S. military and government as a whole to outsource many tasks previously considered ‘inherently governmental’, to be performed only by government employees. In many respects the role of corporate contractors today at Pine Gap exemplifies Patrick Keefe’s judgement that in recent years ‘the relationship between U.S. intelligence and the private sector had grown so symbiotic that it was often impossible to disentangle the two.’[4]

David Rosenberg, who worked in the Operations Room as an ELINT Analyst for the NSA from 1990 to 2008, has written about the contractors as follows:

Contractors have always played a key role at Pine Gap, and over the past forty years have helped with the mission in Operations and overall maintenance. Raytheon, the primary contractor inside the secure building, is tasked with manning positions within Operations, and its operators are referred to as ‘rack jocks’ because each operator sits in front of a tall rack of equipment, monitoring data and alerting Operations to anything new that might indicate an impending event. Raytheon also manages the computer network, equipment maintenance and the Engineering division. In times past, Boeing Australia administered the contract for grounds maintenance, housing and the motor pool, but Raytheon obtained this contract in 2004-05, making it by far the largest contractor at Pine Gap.[5]

The corporate sector is now thoroughly involved in a wide variety of management, operational and maintenance roles at Pine Gap, including some which are central to the facility’s core operations. While the base is nominally a ‘joint’ United States-Australian facility, virtually all of the major companies involved are U.S. corporations or their Australian branches – highlighting the heavily asymmetrical character of the ‘jointness’ involved in all aspects of Pine Gap.[6]

Moreover, corporations are not necessarily the best or most objective interpreters of US-Australian security and intelligence priorities or Australia’s national interests. The companies are primarily interested in securing contracts and making profits. Their employees at Pine Gap are mainly concerned with enhancing their technical skills, gaining promotions and obtaining higher salaries – substantially higher than those paid to government employees carrying out the same functions.[7] The result is, as one observer of the wider picture of the ‘symbiotic’ relationship between the U.S. intelligence community and the private sector put it,

‘However patriotic they might be, …there is a subtle but fundamental misalignment between [contractors’] priorities and incentives and those of their clients in America’s intelligence community.’[8]

Advocates of the outsourcing of U.S. intelligence work maintain that two key requirements of contemporary intelligence are ‘flexibility’ and a capacity to ‘surge’ operations in response to a changing environment:

‘… intelligence contractors ensure the necessary organizational flexibility that is pivotal in an unpredictable world, where the intelligence community must be able to increase or decrease its resource base at very short notice.’[9]

In support of the need for such a surge capacity, advocates often point to the post-9/11 environment. Yet, a decade and a half later, elevated contractor numbers show no sign of diminishing.

Moreover, the companies involved at Pine Gap have poor operational security (OPSEC) standards. Many of their job advertisements have evidently escaped scrutiny by the official agencies. Their employees, being civilian workers on relatively short term contracts, rather than intelligence officials, have no alternative but to seek further work by describing their jobs on social media and highlight their skills on LinkedIn.[10]

The companies also tolerate behaviour which would not be acceptable in the case of the CIA and NSA personnel at the station. Rosenberg has reported, for example, that in the early 2000s, ‘one contractor’ was forced to leave Alice Springs because of ‘unacceptable behaviour’ in a bar in the town. However, ‘he survived this incident, managed to retain his security clearance, and continues a successful career with the same contractor at another overseas posting’.[11]

Where almost three-quarters of the personnel at Pine Gap are employees of private U.S. corporations and their sub-contractors, and fewer than one in ten were Australian government employees, the question of whether this facility, which the Australian government maintains operates with its ‘full knowledge and consent’, does so in the national interests of both governments, or indeed, the wider human interest, needs closer assessment. [12]

The remainder of this Special Report is available as a PDF here

III. References

[1] Desmond Ball, Duncan Campbell, Bill Robinson and Richard Tanter, Expanded Communications Satellite Surveillance and Intelligence Activities utilising Multi-beam Antenna Systems, Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, (NAPSNet Special Report, 28 May 2015), at https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/expanded-communications-satellite-surveillance-and-intelligence-activities-utilising-multi-beam-antenna-systems.

[2] ‘Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap’, Hansard (House of Representatives), 14 May 2008, p. 5030;

and information provided by the Australian Department of Defence, 18 June 2015.

[3] Tim Shorrock, Spies for Hire: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing, (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2008), pp. 264-265.

[4] Patrick Keefe, ‘Privatized spying: the emerging intelligence industry’, in Loch K. Johnson and Josiah Meigs (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, New York: OUP, 2010, p. 297.

[5] David Rosenberg, Inside Pine Gap: The Spy Who Came in From the Desert, (Hardie Grant Books, Melbourne, 2011), pp. 40-41.

[6] Richard Tanter, ‘The US military presence in Australia: asymmetrical alliance cooperation and its alternatives’, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 45, No. 1, 11 November 2013, at http://japanfocus.org/-Richard-Tanter/4025/article.html.

[7] According to the head of personnel for the U.S. intelligence community, in 2008 agencies ‘spend about $125,000 a year for a government employee, compared with about $207,000 for a contract worker.’ Greg Miller, ‘27% of U.S. spy work is outsourced’, Los Angeles Times, 28 August 2008, at http://articles.latimes.com/2008/aug/28/nation/na-cia28

[8] Keefe, op.cit. p. 297.

[9] Morten Hansen, ‘Intelligence Contracting: On the Motivations, Interests, and Capabilities of Core Personnel Contractors in the US Intelligence Community’, Intelligence and National Security, 29:1, p. 78.

[10] Some contractors, including former intelligence agency employees, appear all too ready to disclose their work at sensitive intelligence facilities. Philip Dorling, ‘Spies blow their cover through the internet, The Age, 26 December 2012, at http://www.theage.com.au/technology/technology-news/spies-blow-their-cover-through-the-internet-20121225-2bvaf.html

[11] Rosenberg, op.cit., p. 135.

[12] Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap: Full Knowledge and Concurrence, Hansard (House of Representatives), 26 June 2013, p. 7071; and Richard Tanter, The ‘Joint Facilities’ revisited – Desmond Ball, democratic debate on security, and the human interest, Special Report, Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, 12 December 2012, at https://nautilus.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/The-_Joint-Facilities_-revisited-1000-8-December-2012-2.pdf.

Cover image: Here.com and Richard Tanter

One thought on “The corporatisation of Pine Gap”