ALEX WELLERSTEIN

AUGUST 8, 2019

I. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, Alex Wellerstein sketches a framework for thinking about how concentrated nuclear use authority should be at the top. While he discusses specific US proposals for reform in response to the debate about President Donald Trump’s fitness, the scope of his analysis is global and includes all nine nuclear weapons states.

A podcast with Alex Wellerstein, Peter Hayes, and Philip Reiner on NC3 decision-making is found here.

Alex Wellerstein is a historian of science and nuclear weapons at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey

Acknowledgments: The workshop was funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

This report is published simultaneously here by Nautilus Institute and here by Technology for Global Security and is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

Banner image is by Lauren Hostetter of Heyhoss Design

II. NAPSNET SPECIAL REPORT BY ALEX WELLERSTEIN

NC3 DECISION MAKING: INDIVIDUAL VERSUS GROUP PROCESS

AUGUST 8, 2019

Summary

Summary In this paper I will sketch a framework for thinking about how concentrated nuclear use authority should be at the top—while discussing some of the specific proposals that have arisen.[1] Almost all of my main examples come from the context of the United States, both because this is my own area of deeper experience, but also because the United States released considerable doctrine, testimony, and declassified documents that highlight aspects of the history and present to a degree unmatched by any other nuclear power. Additionally, the debates about Donald Trump’s fitness to have access to “the nuclear codes” played a strong rhetorical role in the 2016 Presidential election. As a result much of the specific policy discussions has taken place in this context. But this framework must be expanded to a global perspective, and I have looked to other national nuclear programs about other possible arrangements.

Introduction

The uncertain political situation in the last two years, with the global rise of populist, right-wing, anti-elitist politics, has resurrected long-dormant debates about nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) decision making. In practically every nuclear-armed state, it appears to be the case at the dawn of the 21st century that nuclear use command authority—which is to say, the question of who is authorized to order the employment of nuclear weapons in a military situation—is concentrated in a singular head of state. Doubts have arisen, particularly in the American context, about whether this concentration of use authority in a single individual is wise, given the fallibility of all human beings, and particular with regards to the specific qualities which have been attributed to President Donald Trump by not only his critics but even many of his enablers: impulsiveness, emotional instability, willful ignorance, disdain of national and international norms, and possible non-commitment to the idea of non-nuclear use.

In many cases it is apparent that the question of “whose finger should be on the button,” as it has often been framed, is one of political football. There have been, however, a few serious proposals for how nuclear authority could be modified in ways that might prevent an ill-advised use of nuclear weapons by a singular head of state, but there has been little systematic meta-analysis of these proposals, and the issue of whether nuclear use authority should be concentrated in a singular individual has tended not to be the focus of the larger academic literature on NC3 issues, despite it being a frequent component of critiques of nuclear weapons and popular discussions of command and control.[2]

In this attempt at a brief paper I sketch out a framework for thinking about this particular question—how concentrated should nuclear use authority be at the top—while discussing some of the specific proposals that have arisen. Almost all of my main examples come from the context of the United States, both because this is my own area of deeper experience, but also because the secrecy surrounding nuclear employment makes it very hard to talk about it with any specificity at all, and despite its own copious secrecy the United States has at least released considerable doctrine, testimony, and declassified documents that highlight aspects of the history and present, to a degree unmatched by any other nuclear power. Additionally, the debates about Trump’s fitness to have access to “the nuclear codes” played a strong rhetorical role in the 2016 Presidential election, and as a result much of the specific policy discussions have been taking place in this context. But I would like to believe this framework could be expanded to a more global perspective, and I have looked to other national nuclear programs especially for inspiration about other possible arrangements. As a historian I would be remiss if I did not point out that the NC3 systems that exist in the various nuclear nations are historically constituted and contextualized. None of these arrangements came “out of nothing,” none of them are “obvious,” and many of them resulted only after considerable debate and experimentation.[3]

This paper is born in part out of a frustration of mine that this topic, which is a key part of not only our present context but the entire history of nuclear weapons, is so quickly brushed off without serious consideration. In reading and talking to scholars about this issue for the past few years, the main motivations for neglecting this topic appear to come down to the following concerns:

- Confidence in the status quo. Arguments along the lines of, “so far this hasn’t been a major problem,” are, I think, not really in the spirit of critical examination (we haven’t had a nuclear war yet, but that hasn’t stopped endless other discussions about the possibility that it could occur) and also tend, in my mind, to overestimate the stability of NC3 systems over time (despite the fact that any serious historical examination will show that there has been considerable revision in assumptions, policies, tactics, and concerns over the years). The current systems were built in a particular context with particular expectations; we should be prepared to reevaluate whether they hold in the present or into the possible plausible alternative futures which we see before us.

- Fear that rapid change could be destabilizing or have unintended consequences. This is fair enough, but showing whether this is true or not (and what kinds of changes/consequences we should be concerned about) should be a stimulus for study, not an excuse to halt the conversation.

- There is too much secrecy to discuss this seriously. There appears to me to be adequate information in the public domain on the operation of at least the American NC3 system to sketch out possibilities. Certainly, secrecy makes specific recommendations difficult. But it does not stop us from having many other conversations about nuclear weapons. And, as a historian of nuclear secrecy in particular, I will say that relegating this discussion entirely to the classified sphere traditionally has limited the imagination of possibilities. And if we are going into this with all the wrong assumptions, perhaps someone on the “inside” will find a politely sanitized way to convince us of this, and something will be gained from that.

- There is no way for us on the “outside” to make this policy change. There are not always clear external paths for changing NC3 policy, even in democratic nations, because it is frequently made only by means of internal military or executive regulations and not legislation. Again, this seems not to have stopped other discussions of NC3 policy questions, so it is curious that this topic attracts this particular objection. It is also the case that some of these policy avenues are prematurely dismissed (in the United States, the Constitutional/legal issues are murkier than they at first may appear). In any case, inability to easily change policy is a bizarre criterion for policy discussions.

Ultimately, my hope is that this paper will stimulate conversation and criticism. It is not intended to be the be-all and end-all of this particular subject, and I represent myself primarily as a historian, not a policy analyst, so my understanding of the issue, and feeble attempts at policy analysis, should be read through that lens.

Specifying the Issue

There has been much written on NC3 decision making in general, and I want to be very specific about what question is being asked. I am not talking about: how states should decide whether to use nuclear weapons (e.g., counsel, evaluative processes, legal processes), nor how or whether authority should be delegated or subject to succession (e.g., predelegation, continuity of authority), nor, really, the question of military versus civilian authority, though all three of these topics do obviously intersect very strongly with this issue. I am more specifically asking the question: in whom should the authority for use be given in the first place? Should it be a single person, or many people? I think we can take for granted, in this discussion, that over the course of the 20th century, for whatever various historical reasons, the norm developed that the use of nuclear weapons was considered as much a political decision as anything else (as opposed to a purely tactical or military decision), and so it should not be left to the discretion of merely anyone with physical access to the weapons as to whether they should be used. There are exceptions to this norm, such as predelegation, but even these situations presume that some more authoritative body (whether civilian or military) was granted the authority in the first place, prior to delegating it “downward.”[4]

Present-day US Air Force doctrine states unequivocally that, “the President retains sole authority for the execution and termination of nuclear operations.”[5] This has been a codified policy since 1948, though arguably it has been de facto policy since August 10, 1945, when Truman ordered that no further atomic bombings could be conducted without his explicit authority, and has frequently been interpreted as an implied policy since the passing of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946.[6] The presence of this statement in the United States Air Force doctrine has a clear implication: it is not the responsibility or authority of the military writ large (much less the individual soldier) to make policy decisions about the use of nuclear weapons. The doctrine continues in other parts to explain that this is due to the unusually political nature of said weapons.

No one to my knowledge disputes this fundamental assertion that the President is the only one who can positively give orders to use nuclear weapons, outside of instances in which the President has delegated that authority downward. The areas of contestation have arisen instead in the context of what is sometimes called the “crazy President” scenario: what if the President went insane and suddenly wanted to order the use of nuclear weapons “out of the blue”? This scenario was first raised in earnest in the wake of Richard Nixon’s presidency, when he was rumored to be prone to drinking, melancholia, and “madman” outbursts about nuclear weapons, but it has been resurrected occasionally since. The general argument against worrying about such a scenario is that in between a head of state giving orders, and the actual launching or dropping of nuclear weapons, there are many other people. And presumably these people, faced with an obviously insane order, would defy it. In the US this has in the past been centered on whether the Secretary of Defense could simply not pass on said order to the military, but in the last year or so this objection has largely been quashed, in part because of statements from at least one former Secretary of Defense (William Perry) that confirmed what some analysts (such as Bruce Blair) had been arguing for a long time: that the Secretary of Defense served primarily an advisory role on nuclear use issues, and could be easily bypassed by a determined President.[7] In more recent discussions, such as the November 2017 Congressional hearing on the matter, the locus of defiance has moved to the military, such as the head of Strategic Command, whose participation would be required for execution of the order.[8]

I do not adhere to the “crazy President” framing, in part because it smacks of straw man (despite the fact that one can document modern and pre-modern Presidents who had declining and questionable mental states since their elections, brought about by a wide variety of factors), but also because it fails to take into account many tricky real-world dynamics that might play out in practice. For example, when one says an order is “obviously insane,” what does one mean? Generally, NC3 discussions resolve this by talking about the “context,” that is, if the order comes at a time of total peace, or is abrupt and without apparent full examination. Aside from the fact that global context shifts rapidly, and crises are a frequent part of that, I believe any psychologist would agree that mental illness ought not be considered a simple bout of temporary non-linearity, but as something more subtle and often methodical. It is a bad model of real human behavior, and a bad model for thinking about how use orders should be considered. One might add whether one should just include “terrible and escalatory response to a crisis” or “bad judgment encouraged by bellicose advisors” to the list of these we might want to worry about beyond the “crazy president” and other ill-informed and frankly parodic (at best) models of mental health.

But as a framing mechanism, let us say that the issue at hand is whether a single human being, however extensively vetted (or not) at the time of being installed (democratically or otherwise) into the position of head of state, should have this authority vested in them, and whether or not there should be formal processes other than refusal to follow orders (and all of the psychological, political, legal, and even ethical questions that implies) to “check” whether or not that authority has been used wisely. Is the possibility of a poor decision by the top holder of nuclear use authority, one that many others would agree was poor but feel compelled to carry out anyway, a real one? In the United States, I can imagine situations in which one would say, “yes,” and the answers from the recent testimony were not in my view especially reassuring (they seemed to reveal, in my reading, that the military construed this narrowly as an issue related to the Laws of Armed Conflict, and did not have any formal procedures in place for what to do in the event of an insistent President).[9] Certainly I think it becomes more plausible (for Americans at least) if we instead imagine how this might play out in other nuclear-armed nations.

Arguments for Unitary Authority

In thinking analytically about what is gained and lost in these arrangements, and what is at risk, let us look briefly at the arguments in favor of a unitary executive making the decisions about nuclear weapons, stated or unstated, as they appear:

- In a crisis, nuclear use decision making may need to be made extremely rapidly. This applies very well for countries whose nuclear weapons are in a “use it or lose it” sort of situation, or whose abilities to detect and/or weather an incoming nuclear attack are poor. It was the guiding philosophy of the US-Soviet dynamic during the Cold War, when the US in particular feared (rightly or wrongly) that the Soviet Union might conduct a “bolt out of the blue” attack that would try to cripple American nuclear response capabilities. Assuming one buys into the idea that this dynamic is still required (there are those, such as Blair and Perry, who have argued that the US posture should instead be confident in absorbing a first-strike without the need for a concurrent retaliation), this is a consideration that cannot be easily waived away, especially when one takes the perspective of nations outside of the US-Russian dynamic today (e.g., India-Pakistan).[10]

- Adding additional complexity or uncertainty of authority might erode deterrence posture. If a national nuclear policy is based on the idea of deterrence (a big “if,” historically), then the threat of retaliation must be credible. Additional complexity in nuclear use procedure could lead an adversary to think that the NC3 system could be “gamed” (by eliminating one of the necessary authorities), or have a low probability of decisive judgment. I think this is a worthy consideration, although I would note that the existing NC3 systems are all compromises of the always/never dilemma, and many do add additional complexities (two- and even three-person rules, “codes,” PALs) that a fearful mind could imagine leading to an erosion of deterrence credibility (and such measures, especially technical ones, have been at times resisted by military commanders for just this reason).[11] An avoidance of the “gaming” problem could be to have whatever system in place “degrade” to a unitary one under certain pre-determined circumstances (which could possibly dis-incentivize any attempt at “gaming”).

- Decisive leadership is necessary in the event of something as weighty as nuclear use questions, and that can only exist in an individual mind. This is a more abstract issue, one that combines issues of psychology, sociology, and philosophy. It is rarely stated explicitly by advocates of the status quo, but it is frequently invoked by critics as an inherent property of technological systems that contain the possibility of great technological mishap.[12] It is a variation of Plato’s classic argument that a ship must contain but a single captain. I think we ought to recall that Plato, from this argument, extrapolated that a dictatorship was the only way that a state could be run. In fact, there are many ways to run a state, even though some are principally more efficient than others (and in practice, despite the lore about making “the trains run on time,” unitary dictatorships have typically not been very efficient compared to other state governance models, but I digress). I have not seen discussions about this issue that have referenced the extensive body of sociological and psychological work on the decision-making effects of “group size” that has evolved over the past century, following the initial investigations by sociologist Georg Simmel in 1908 (which argued, as a colleague of mine has pithily put it, “two people can get things done, but three or more gum up the works”), but as a historian of science and technology I will only note that while technological systems do constrain policy outcomes, over-investment in the idea that the technology itself dictates every detail of its handling practices is frequently revealed to be as untrue as Plato’s assertions about the inherent nature of the state.[13]

- Nuclear weapons are objects of international policy and, as a result, need to be subjected to strong civilian authority primarily. This is often how this issue is framed, in part for historical reasons. In the early decades of the nuclear age, a unitary civilian authority was considered a “safety catch” on the “trigger” to use nuclear weapons, to use Paul Bracken’s evocative analogy. The assumption in the United States, emphasized in the Truman administration in particular, was that the military would be especially ready to use nuclear weapons in the event of war, and that the civilian leadership would be less so.[14] It is of historical note that this assumption appears to have been probably correct during the Cold War, at least through the 1960s, when Presidents several times served as an effective “catch” against more bellicose military advice.[15] Today, whether one questions whether the President might be the one trying to pull the “trigger” against the military’s “catch,” I get the feeling that the post-Cold War stance of the military in the United States has changed quite dramatically (one rarely hears of military generals advocating for any kind of normalization of nuclear use, though one can easily find civilian analysts who encourage this position). In any case, I agree with its sentiment entirely, though I would note that one can still have civilian authority that is not unitary (e.g., authority could require the positive assent of two civilians), so it may seem like somewhat of a non-sequitur. In fact, this can be used as an argument against unitary executive control: if the military is expected to embody the “veto” power, this is arguably a violation of civilian control of nuclear weapons. (I suspect the norm of civilian control in the US, now firmly entrenched, would lead to extreme hesitancy on behalf of the military to otherwise exert such power except in the most extreme of situations.)

As I have made clear, I do not find all of the above equally compelling. In making an objection to unitary control, along with possibility of ill-advised use, I might add two more somewhat abstract arguments. One is that, as Bracken puts it, under civilian control, nuclear weapons “belong to the state, not to the individual in office and not even to the office itself.”[16] In context, Bracken brings this up as yet-another argument against military authority to use weapons (and one might easily, again, turn this into an argument against military’s authority to refuse use of nuclear weapons). But I think it serves a useful reminder that in thinking about these issues broadly, we are allowed to separate here (as we do in the case of continuity of authority questions) the question of use from the specific individuals involved.

Secondly, I would note that in the American context, frequent appeal is made to both “letter of the law” and the Constitution as enshrining the unitary authority principle. Both of these strike me as red herrings. There is no law in the United States that stipulates a procedure or authority for nuclear use specifically. The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (the 1954 revision did not change this aspect) is the only relevant piece of legislation, and it specifies only that the President is the one who can authorize the transfer of weapons from civilian custody to military custody. This is not the same thing as designating use authority, and it was not seen as the same thing even under Truman (who did, in the end, transfer some weapons into physical military custody but never gave positive authority for use to the military). And the US Constitution, unsurprisingly for an 18th-century document, says nothing about nuclear weapons. As is well-known, it divides military power between the President and Congress, giving the former the Commander-in-Chief position and the latter the power to declare war. Where nuclear weapons fall in this dichotomy is not obvious, even if Congress’s control over the war power has become contested (or degraded) over the course of the 20th century. I point these out merely to indicate that these issues, including the Constitutional one, are hardly cut-and-dry. Historically these kinds of arguments emerged to justify, post hoc, the emerging American procedures and norms about nuclear authority. They are flimsy grounds to base an argument for unitary control.

Lastly, I would just note: for anyone who feels the current system is “safe” enough because of the odds of a “veto” by the military (or whomever else one thinks could or would exercise such veto power), I would challenge them to answer, “why not formalize it?” Is there a strong reason for having a system where such “veto” power is entirely informal and subjective to judgment? The well-known case of Harold Herring poses this question in an evocative way: if the individual soldier in the silo is not trusted to make such a judgment call (which I think most would agree is valid, even if they disagree on the way the Herring case turned out), who ought to be? Aside from the safety issues, this is a critical issue bearing on the civilian-military relationship, and with deterrence credibility. Whatever the answer, having it be ad hoc seems to be perhaps the most problematic of all possible worlds, because it means that considerable uncertainty might be injected into a complicated and dangerous situation in anything but the most obviously “crazy” orders. Perhaps we should agree that someone ought to have veto power, or we should perhaps clarify truly that we believe that nobody should. If the former is less scary than the latter, then we need to talk about who.

Possible Sources for Veto Power

Nuclear use authority has been most commonly framed in terms of positive and negative control. Positive control means that the use authority (e.g., the President) is the only one with the ability to issue an assertive use order; negative control means that nobody else can use such weapons on their own authority. The question of a “veto” sits somewhere in between these concepts, as I see it. If we imagine another entity (let us say, the Secretary of Defense) who is required to give an additional positive assent to a use order, and can either withhold it or completely prevent it from percolating, then this in practice is a form of negative control as well. There have been several proposals over the years, most in the last three years, about what kind of entity should or could hold that relationship in the United States in particular. To be brief, I will not describe these proposals in any depth, and, as a result, am stripping them of much of their nuance.

Several can be put into the category of “no first use except,” where the except involves approval from some kind of additional authority with veto power. This construction appears to be quite deliberately an attempt to disarm any objection that this would erode deterrence posture. For example, in 1972, US Representative Ron Dellums introduced a simple act that decreed that, “The President shall not order the first use of nuclear weapons anywhere in the world, except in response to the use of nuclear weapons by others, without prior authorization by Congress.”[17] Jeremy Stone, then President of the Federation of American Scientists, proposed in 1975 that a President could not use nuclear weapons first “without consulting with, and securing the assent of a majority of, a committee composed of the speaker and minority leader of the House of Representatives, the majority and minority leaders of the Senate, and the chair and ranking member of the Senate and House Committees on Armed Services, the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, the House Committee on International Relations, and the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy.”[18] The present Markey-Lieu bill (2017) would require a “declaration of war by Congress that expressly authorizes such strike” for first use to be available to a President.[19]

These proposals have their merits and their problems. Separate from the question of whether a “veto” is necessary, the best argument in favor of them as specific resolutions to the “veto” question is that having Congress, in some form or another, be the “veto” satisfies two pleasing criteria: they are an elected body that is meant to represent the nation as a whole (unlike, say, a military commander or an unelected member of the President’s cabinet), and, in the US, it would fall more neatly into the constraint of the Constitution’s division of the war powers. The arguments against such a proposal are, however, numerous and arguably serious. The inability of achieving Congressional agreement on such a contentious and weighty matter as first use seems patently obvious in any post-World War II context (much less the one I am writing this in), and even the Stone proposal looks unwieldy with its requirement of assessing the opinion of a dozen people and requiring a majority agreement. The mere attempt to get such assent could lead to international crisis. I do not think I mischaracterize these attempts as being simply No First Use wolves packaged in sheep’s clothing; I don’t think anyone proposing or advocating these bills actually thinks Congress would ever authorize a first-use action.

A more counterintuitive criticism is one made by a later analysis of the Stone proposal, which noted that, contrary to this particular narrative of nuclear use, the US Congress has frequently been more than willing to enable Presidents to wage war (including without formal declarations of it), and individual members of Congress are frequently much more bellicose than their President.[20] I bring this up only as a note that the framing of who is or isn’t trying to pull or stop the “trigger” is of course contextual.

Whether a No First Use policy would solve this issue is a question that has come up in my discussion of this with advocates of these policies in general. It appears to me that it would resolve some of the most pressing of the scenarios—a “crazy President” would not be capable of doing anything rash with nuclear weapons first, and even “President under pressure” scenarios would fail if such a policy was truly codified in doctrine and/or law. But I would note that there are some strong objections to No First Use policies (not just the often-stated one of the value of ambiguity but also issues regarding alliances and credibility). Separate from these, I would also suggest that while No First Use would obscure some types of ill-advised nuclear use scenario, it would not solve all of them in a world where there are several plausible pathways to “use” by nations or non-state actors that would not adhere to such a policy. As a simple example: imagine a nuclear terrorist attack took place; would this immediately give a President a “blank check” under these proposals? Another: imagine a fledgling “rogue state” that, for whatever reason, launched a solitary missile at the United States. Would the US President, under these conditions, be allowed to retaliate in kind (or more so), without any “check”? (Does it matter if the missile failed in mid-air or was destroyed?) I do not raise these things to be tricky, I merely want to point out that one can imagine bad executive use of nuclear weapons even with a solid No First Use policy in place. At the very least I think these things ought to be hashed out in more detail.

Another variation on the veto question is simply to specify some other number of people who might be required before a weapon use could be authorized. As already noted, such a system could “revert” back to unitary decision-making under pre-specified conditions. One specific proposal is that of Lisbeth Gronlund, David Wright, and Steve Fetter, members of the Union of Concerned Scientists, whose proposal (in brief) would require the President to get active consent from the next two people in the line of succession (normally the Vice President and the Speaker of the House) before nuclear use orders would be carried out by the military. Should they be impossible to communicate with within a reasonable amount of time in a crisis, the system would revert to unilateral authority.[21] Another even simpler variation of this would be to formalize the system that many people believe is actually already in place: that the Secretary of Defense would have an active “veto” role. Again, one can imagine pros and cons about different “veto” holders (would the Secretary of State be more appropriate than that of Defense?) and number of assenters (from the “full vote of Congress” requirement, down to the dozen of the Stone proposal, down to the two of the Gronlund-Write-Fetter proposal, down to the one of the minimal “Secretary of Defense can veto” idea). Smaller numbers may be more effective but more susceptible to groupthink; larger numbers may involve collective abdications of individual responsibility and become unworkable. This is a discussion, again, that should be informed by work in the social sciences on actual human group behaviors.

An interesting variation on the “veto” concept is the proposal by Richard K. Betts and Matthew Waxman, which essentially makes the Attorney General the “second man” for authorizing a nuclear use order. The Attorney General would be required, under this proposal, to authenticate that a nuclear execute order was “within the president’s authority and proper legal bounds” before it would be valid.[22] I am not sure this adds sufficiently more variation or interest to the previous situations discussed, but it dovetails into a more general question of whether, in the US anyway, the Laws of Armed Conflict (LOAC) would be sufficient to avoid rash use. Arguing that the LOAC would allow the military to refuse “out of the blue” nuclear orders was broached recently in response to fears of Trump’s potential nuclear use issue by a former head of STRATCOM, and later by public remarks of the organization’s current head. It is interesting in that it is largely absent from pre-Trump discussions of this topic—it would be interesting to know how it became the apparent new “official line” (is it coordinated or serendipitous?). I am personally not convinced that adherence to LOAC alone would avoid rash first-use; US nuclear posture is supposedly planned to be in respects to LOAC, and this has not discouraged the creation of elaborate war plans of a variety of sizes. The LOAC are notoriously open to local interpretation, and the US has stated many times over the years that it does not view the LOAC as being inherently contradictory with many forms of nuclear weapons employment. Furthermore, this also imagines the dispute over a given nuclear use would be constrained as a narrow legal debate, which is, I suspect, not especially reassuring to anyone who has seen lawyers arguing over technicalities.[23] In any event, it is not clear to me that “legality” is the defining criteria for insuring that weapons are not rashly used, unless Congress, or an enjoined treaty, very clearly delineated what the requirements for “legal” nuclear weapons use would be, which is an obviously thorny area (though it does present, perhaps, a way forward in thinking about how to enact policy in this area).

Finally, there is a category of proposal we might describe as “systematic modification,” in which the NC3 system itself undergoes a massive change in a way that would make it easy to simply ban rapid execution of orders. Bruce Blair proposes that the US (and presumably other nations) could shift towards entirely second-strike capabilities, phasing out “use it or lose it” and “launch on warning” systems like ICBMs, and that this would allow for a system in which there were no pressures to rapidly execute any nuclear orders.[24] This is perhaps the most radical solution to the issue, for better or worse, and could be considered an effort to undo the conditions that produced the status quo in the first place.

Comparative Systems

Given the uncertainties that exist about the functioning of the American system of nuclear command authority, it is not surprising to find that a comparative picture is somewhat difficult to carve out. Even when information is available, it is subject to ambiguities about how these systems might work in practice or how flexible they might be. There are advantages and disadvantages in building flexibility and redundancy into such systems, and we know that the United States at various times in its history did build in considerable flexibility of its own, and it may still have some aspects of that (for example, both the head of Strategic Command and the Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff are listed as conduits of command authority to the military—it may be the case that either can serve that role under specific circumstances). In this section, I want to look at how several international systems work as well as introduce a diagrammatic approach that I believe may help in clarifying the command question, specifically in indicating who may initiate a nuclear execute order and who may be able to confirm or veto the order as the command authority flows onward.[25]

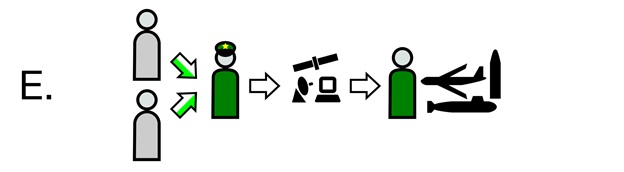

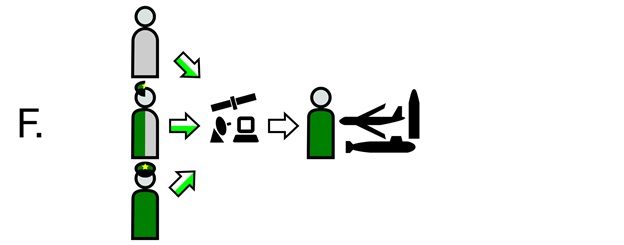

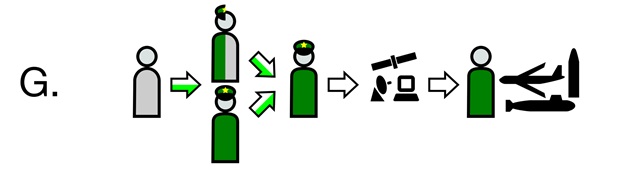

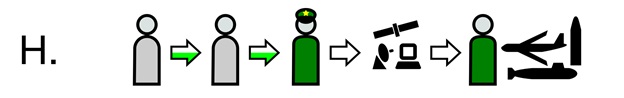

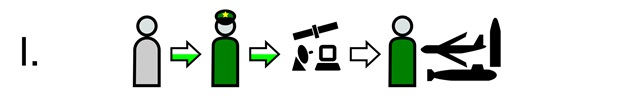

The diagrams in this text are meant to illustrate several real and hypothetical ways in which nuclear command authority might be transmitted and translated into action. The characters on the far left are civilian state authorities (in gray). The character with the star on their hat is a top-level military authority (in green). The satellite/radar/computer represents the human and technical complexities of the command, control, and communications systems that transmit orders to, finally, the lower-level military figure (in green, no hat) who represents the officers who actually carry out the order with regards to the “shooters” (bombers, submarines, missiles, etc.).

Green arrows represent the ability to give positive or negative authority, whereas white arrows, in principle, are meant to be implementations of orders. Half-green arrows indicate the order only contains part of the necessary authority (one full green arrow is necessary for an order to be authenticated, so two half-arrows). One can ask whether every white arrow will flow naturally or whether there is the possibility of “push back” of some sort (e.g., a “veto,” whether sanctioned or as either deliberate disobedience or just failing to convey orders forward), but in principle the white arrows are not intended to be “vetoes.”

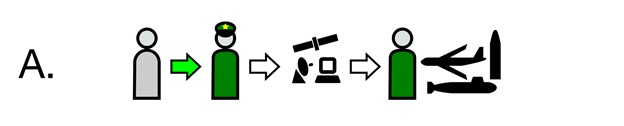

Diagram A

Diagram “A” indicates how the system works in the USA, as far as I can tell: the President of the United States is the only one who can give a positive use order, which goes to a top-level military figure (either the head of Strategic Command or the Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff), who then conveys the order onward. The head military officer is not given an explicit veto power but could disobey orders (at their peril, etc.) for various reasons.

This same diagram could be used for the United Kingdom, as well, with the Prime Minister as the chief political figure, with an even further emphasis on the fact that once the order is entered into the military realm there is meant to be no discretionary power on behalf of the military, in strict preservation of the civilian-military split. It is of note that in the early UK nuclear system, the power was more closely vested in the military than the civilian forces.[26]

In India, this authority resides in the Prime Minister as head of the Political Council of the Nuclear Command Authority. In Pakistan, the nuclear capability was initially vested in the President of Pakistan as head of the National Command Authority, but it transferred (first procedurally, then legislatively) to the Prime Minister in 2010. It is unclear if these systems look like the flow in diagram “A,” but they may.[27]

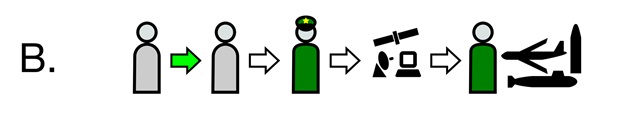

Diagram B

Diagram “B” shows how many people think the system works in the USA, with the US Secretary of Defense being a necessary “node” in the flow of command authority. Again, nobody has suggested that this is meant to be a “veto” position, but many have argued that the Secretary of Defense could defy orders if they disagreed with them. Again, this is not apparently how it works. I have left out the fact that in principle the President should be talking in a consultative way with the Secretary of Defense (and many others); consultation, while an important part of the process, is not mandatory and is not part of the flow of command authority as I have interpreted it, since none of those who are consulted have their consent required or have any veto power, and the President need not listen to any of them.

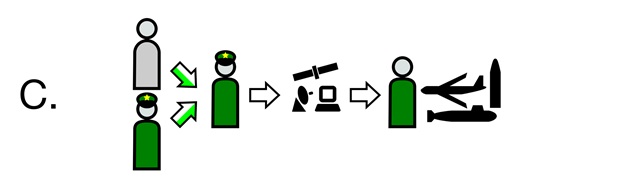

Diagram C

Diagram “C” shows one version of what is represented as the French system. In this, the President has half of the “codes” necessary to unlock the weapons. The other half is carried by the Chef d’État-major particulier (CEMP), a high-ranking military officer in the President’s cabinet. The President initiates the use order, but it must be concurred by CEMP. The order is then authenticated by the Chef d’Etat-major des Armées (CEMA; equivalent to the Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff), which relays it to the C3 system and subsequent forces.[28]

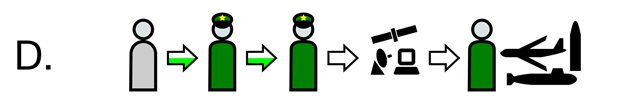

Diagram D

When reading descriptions of the French system, it is not clear to me whether the CEMP could initiate the order, or whether the initial command order must come from the President. In the event that the President is the only one who can initiate a command use, then the French system would look like diagram “D,” above. Differentiating between “C” and “D” lead to interesting questions about the nature of nuclear command authority, hence the difference in interpretations is, I think, worth pointing out.

Diagram E

Diagram “E” shows the system in the People’s Republic of China, as it is believed to work, in which the heads of two civilian committees are required to initiate nuclear use. It is worth noting that at the moment, the same person (the head of state) is the head of both committees, but in principle they could be separated. When they are the same person, it is functionally equivalent to “A.” Clearly, any nuclear command authority system that designates multiple roles as a means of creating a “check” should not be allowed to consolidate those roles in a single person.[29]

Diagram F

Diagram “F” shows the system, as it is believed to work, in the present Russian Federation. In this, three people (the President, the Minister of Defense, and the Chief of General Staff) carry “chegets” (emergency communication satchels) that allow them to authorize a nuclear strike, and at least two “votes” are necessary (so one full green arrow). Whether any one of these votes is privileged (e.g., is the President always required?), is unknown. Note that the Minister of Defense frequently has military rank, but this is not required (and several have not been military personnel), hence their ambiguous representation here. The Chief of General Staff has always been a high-ranking military officer. The activation of the “chegets” appears to go directly into the communication systems without an intervening officer. It is of note that in the Soviet Union, the Politburo apparently had the ability to collectively give a military authority nuclear command authority; this is an interesting alternative scheme that does not involve a simple use order but a specific form of delegation.[30]

Diagram G

As with the French case, it is unclear if each of these “voters” can initiate the schema in the Russian schema (that is, if they are equally “weighted” with command authority). It has been suggested that perhaps only the President can initiate the order, and then someone else would be required to confirm it. If that were the case, it would look something like diagram “G,” above, which is an interesting variation on diagram “D.”

Diagram H

Diagram “H” shows the hypothetical proposal discussed at the end of the paper, in which the President/head of state would need their order not only conferred but explicitly agreed to by another civilian cabinet member. One can think of it as a “strong” version of case “B.”

Recent information indicated that Israel may have a system of this sort, in which two people — the Prime Minister and the Minister of Defense — must give mutual assent for any nuclear use to be undertaken. In cases where the Prime Minister is the Minister of Defense (as has frequently been the case), this secondary role is assigned to another minister.[31]

Diagram I

Lastly, for contrast, diagram “I” shows another hypothetical arrangement, in which the chief military officer would have an explicit veto power (they would not be able to initiate a nuclear execute order, but their explicit concurrence would be necessary for one to be carried out). If one believes the military does serve as a “check,” this would be a stronger version of case “A.” There are severe conceptual and practical problems with this approach, though: it calls the civilian-military split into grave question, and for this reason, the UK has apparently worked to make sure that theirs is definitively a system of “A” and not “I.”

Nothing to my knowledge has been authoritatively stated on North Korea’s procedures, if they have even formalized them (one of Salma Shaheen’s observations is that nascent nuclear powers have tended to take several years to formalize their use procedures, and that it is a characteristic of several nations that they frequently start out under ambiguous military control and drift towards more centralized, civilian control). In all of these cases, it is entirely unclear whether any other people, governmental bodies, or military commanders have been given any kind of formal “veto” power.[32]

Which of these approaches, if any, points the way forward? What other possibilities are there, especially if one takes a less US-centric position? Are these situations better or worse than the ambiguous status quo? At this point, I will conclude that I think this discussion could be much more mature than what I have laid out above, and indeed, again, my hope is that this overview will stimulate further analysis, more than give a concrete answer. As is patently obvious, I do think that entrusting nuclear use authority in a single person is dangerous, whoever the person may be (and this is why in every other nuclear weapons context, a two-person rule is considered standard). I also feel that entrusting that “context” and “judgment,” especially at the military level, will prevail in crisis situations and prevent ill-advised use is, as I like to put it, overly optimistic, especially given the potential consequences for failure. Thus, I would be interested in further, more rigorous discussions of the pros and cons of these various sorts of proposals.

III. ENDNOTES

[1] I would like to thank Avner Cohen and the participants of a workshop on these topics held at the Stevens Institute of Technology in March 2018, sponsored by the Ploughshares Fund, notably, Bruce Blair, William Burr, Daniel Ellsberg, Lisbeth Gronlund, Benoit Pelopidas, Stephen Schwartz, Daniel Volmar, and Amy Woolf have all given me food for thought on this topic, though my views are certainly only my own.

[2] E.g., Daniel F. Ford, The button: The Pentagon’s strategic command and control system (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985); Elaine Scarry, Thermonuclear monarchy: Choosing between democracy and doom (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014); Eric Schlosser, Command and control: Nuclear weapons, the Damascus accident, and the illusion of Safety (New York: Penguin, 2013). One might also look at WNYC/NPR, “Nukes,” Radiolab (April 2017): https://www.wnycstudios.org/story/nukes, which the author had a role in producing.

[3] For a very useful framework for thinking about the historical evolution of NC3 systems globally in a comparative context, see the very recently-published monograph: Salma Shaheen, Nuclear command and control norms: A comparative study New York: Routledge, 2019).

[4] This norm was not, I feel compelled to point out, entirely obvious for the first ten years or so of the nuclear age. Despite much scholarly misunderstanding, it was not at all clear during World War II, and was one of the issues that was being “hashed out” in the early decisions about the use of the atomic bomb between people like Henry Stimson and Leslie Groves, and particular Harry Truman’s order to halt atomic bombings on August 10, 1945. It is also the case that there were frequently people who questioned this “norm” as it evolved, even though it is largely taken for granted today. See e.g. Nina Tannenwald, The nuclear taboo: The United States and the non-use of nuclear weapons since 1945(Cambridge University Press, 2007), and T.V. Paul, The tradition of non-use of nuclear weapons (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2009) for discussions of the evolution of attitudes towards the use of weapons, and Michael Gordin, Five days in August: How World War II became a nuclear war (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007) and Alex Wellerstein, “The Kyoto misconception: What Truman knew, and didn’t Know, about Hiroshima,” in Michael D. Gordin and G. John Ikenberry, eds., The Age of Hiroshima (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, forthcoming 2020) on the ways in which these attitudes specifically were contested during World War II. The most systematic study of the evolution of the norm of civilian control, and the complex issues involved in civilian-military nuclear relations, is Peter Feaver, Guarding the guardians: Civilian control of nuclear weapons in the United States (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992).

[5] Nuclear operations, Air Force Doctrine Document 3-72 (7 May 2009, updated 14 December 2011), on 5, copy online at https://fas.org/irp/doddir/usaf/afdd3-72.pdf.

[6] The codification took place with NSC-30, in September 1948. Prior to this, Truman maintained personal control over the use of nuclear weapons by simply not giving them to the military, as part of the civilian-military “custody” dispute that followed in the wake of the passing of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (which says nothing about the use of nuclear weapons, but does specify that the President is the only one who can authorize the transfer of weapons to the military from the civilian agency that created them). Contrary to much scholarly understanding, Truman did not given any positive order to use the weapons in the first place, though he was aware at least one was going to be used (it is not clear he was aware that a second was, at least not so soon after the first), and felt favorably towards the final plans as he understood them (so he can be considered as giving a passive assent, if you wish). For more on these details, see Wellerstein, “The Kyoto misconception.” I apologize for bogging the discussion down with a lengthy footnote, but given the role of precedence in these discussions, understanding the early evolution of the first NC3 system strikes me, as a historian, as extremely germane.

[7] The idea that the Secretary of Defense is a necessary conduit clearly comes from the chain of command specified National Security Reorganization Act of 1958 and the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986. The latter clearly states (§162(b)) that the normal chain of command can be altered upon the direction of the President (presumably through the many still-classified executive decisions on nuclear employment procedure), so appeal to legislation it is not quite as compelling as it appears. Similarly, confusion about the use of the terms National Command Authority and National Command Authorities (NCA, often used interchangeably) in nuclear doctrine seem to elevate the role of the Secretary of Defense. Reading through published doctrine and testimony, I get the sense that there are several possible ways in which the President can convey a valid launch order more or less directly to the military, whether through STRATCOM, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, or even potentially by direct line to a given commander. But this is one of those areas that is still somewhat hazy, other than the assertions by people who ought to know (like Perry) that the Secretary of Defense plays a primarily advisory role, and whose assent is inessential for a valid execute order to be delivered to the military.

[8] Hearing on Nuclear Weapons Authority before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (14 November 2017).

[9] If one wants to hear more of my opinions on this, see Alex Wellerstein and Avner Cohen, “If Trump wants to use nuclear weapons, whether it’s ‘legal’ won’t matter,” Washington Post (22 November 2017): https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2017/11/22/if-trump-wants-to-use-nuclear-weapons-whether-its-legal-wont-matter/.

[10] Bracken has one of the better discussions of the dangers of “ambiguity of command”: Paul Bracken, The command and control of nuclear forces (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1983), 224-230.

[11] On reactions to PALs, see Peter Stein and Peter Feaver, Assuring control of nuclear weapons: The evolution of permissive action links (Cambridge, Mass.: Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard University, 1987). Shaheen’s discussion of Pakistan’s debates about these issues is extremely interesting (Pakistan is the only state I have heard of which had “three-man” handling rules); see Shaheen, Nuclear command and control norms, ch. 5.

[12] This was an especially potent argument in the field of “technological politics” in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and is echoed in many critiques of nuclear weapons and their alleged corrosive effects on democratic governance. See Langdon Winner, “Do artifacts have politics?,” Daedalus 109, no. 1 (1980), 121-136, esp. 131; Gary Wills, Bomb power: The modern presidency and the national security state (New York: Penguin Press, 2010); and Scarry, Thermonuclear monarchy, for three versions of this argument in an anti-nuclear context.

[13] For Simmel’s work, see ch. 3 (“The Isolated Individual and the Dyad,”), esp. part 9 (“The Expansion of the Dyad”) in Georg Simmel, The sociology of Georg Simmel, Kurt H. Wolff, trans. (Glenncoe, Ill.: Free Press, 1950). I do not invoke Simmel to support this particular argument (which appears to have been created from first principles, not observation); there is a wider literature in both theoretical and experimental sociology and psychology on the behavior of groups, is all I am indicating. An interesting overview of much work in this field can be found in Marko Skoric and Aleksej Kisjuhas, “Magic social numbers: On the social geometry of human groups,” Anthropos 110, no. 2 (January 2015), 489-501.

[14] Bracken, The command and control of nuclear forces, 196-197. See also Feaver, Guarding the guardians, ch. 2.

[15] Tannenwald, The nuclear taboo, goes through many examples reinforcing this point.

[16] Paul Bracken, “Delegation of nuclear command authority,” in Ashton B. Carter, John D. Steinbruner, and Charles A. Zraket, eds., Managing nuclear operations (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1987), 352-372, on 355.

[17] Ronald V. Dellums, “To clarify Presidential power to order use of nuclear weapons in declared or undeclared war,” 92 H.J. Res. 1067 (9 February 1972). (It was reintroduced in 31 January 1973.)

[18] First proposed in 1975, but reintroduced with: Jeremy J. Stone, “Presidential First Use Is Unlawful,” Foreign Policy 56 (Autumn 1984), 94-112.

[19] Ted Lieu, “Restricting First Use of Nuclear Weapons Act of 2017,” H.R. 669, 115th Congress, 1st Session (24 January 2017): https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr669/BILLS-115hr669ih.pdf; Edward J. Markey, “Restricting First Use of Nuclear Weapons Act of 2017,” S. 200, 115th Congress, 1st Session (24 January 2017): https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/s200/BILLS-115s200is.pdf.

[20] Arthur S. Miller and H. Bart Cox, “Congress, the Constitution, and First Use of Nuclear Weapons (part 1),” The Review of Politics 48, no. 2 (Spring 1986), 211-245; and Arthur S. Miller and H. Bart Cox, “Congress, the Constitution, and First Use of Nuclear Weapons (part 2),” The Review of Politics 48, no. 3 (Summer 1986), 424-455.

[21] Lisbeth Gronlund, David Wright, and Steve Fetter, “How to limit presidential authority to order the use of nuclear weapons,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (23 January 2018): https://thebulletin.org/how-limit-presidential-authority-order-use-nuclear-weapons11454.

[22] Richard K. Betts and Matthew Waxman, “The President and the Bomb: Reforming the Nuclear Launch Process,” Foreign Affairs (March/April 2018), 119-128: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2018-02-13/president-and-bomb; Richard K. Betts and Matthew Waxman, “Safeguarding Nuclear Launch Procedures: A Proposal,” Lawfare (19 November 2017): https://www.lawfareblog.com/safeguarding-nuclear-launch-procedures-proposal.

[23] See Wellerstein and Cohen, “If Trump wants to use nuclear weapons,” On the compatibility of US interpretation of LOAC with nuclear weapon use, see See, e.g., Written Statement of the Government of the United States of America (20 June 1995), International Court of Justice, Request by the United Nations General Assembly for an Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons: http://www.icj-cij.org/files/case-related/95/8700.pdf.

[24] Bruce Blair, “Strengthening Checks on Presidential Nuclear Launch Authority,” Arms Control Today (January/February 2018): https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2018-01/features/strengthening-checks-presidential-nuclear-launch-authority.

[25] Aside from the specific citations that follow, see Shaheen’s analysis in ch. 1 and 6, and table 6.1 (on 148) for a useful summary of several states.

[26] Shaheen 2019, ch. 2, esp. 54; discussions with John Gower have aided in sharpening this discussion.

[27] On India, see Shaheen, ch. 4, esp. 95; on Pakistan, see Shaheen, ch. 5, esp. 114 and 122.

[28] Jean Guisel and Bruno Tertrais, Le Président et la Bombe: Jupiter à l’Elysée (Paris: Odile Jacob, 2016), 234-235.

[29] Shaheen, Nuclear command and control norms, ch. 3, esp. 78; discussions with Fiona Cunningham have helped sharpen this analysis.

[30] Pavel Podvig, Russian strategic nuclear forces (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001), 39-42; and Henry D. Sokolski and Bruno Tertrais, eds., Nuclear weapons security crises: What does history teach? (Carlisle, Penn.: Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press, 2013), 4-5.

[31] See Avner Cohen’s paper in this same collection.

[32] On Russia/Soviet Union, see Pavel Podvig, Russian strategic nuclear forces (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001), 39-42 and Henry D. Sokolski and Bruno Tertrais, eds., Nuclear weapons security crises: What does history teach? (Carlisle, Penn.: Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press, 2013), 4-5; on the UK, see Shaheen 2019, ch. 2, esp. 54; on France, see Jean Guisel and Bruno Tertrais, Le Président et la Bombe: Jupiter à l’Elysée (Paris: Odile Jacob, 2016), 234-235; on PRC, see Shaheen, Nuclear command and control norms, ch. 3, esp. 78; on India, see Shaheen, ch. 4, esp. 95; on Pakistan, see Shaheen, ch. 5, esp. 114 and 122. In general, see Shaheen’s analysis in ch. 1 and 6, and table 6.1 (on 148) for a useful summary of several states.

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent

This is an outstanding analysis and contribution to a subject of vital core national security interest.

I have a few comments:

1. The Diagram A indicating that the U.S. president orders flow directly to a general officer and then to the executing commanders does not coincide exactly with operational reality. Under past and current arrangements, the president’s order would be passed to the Pentagon “war room” at the NMCC whose titular director is a 1-star J-3 (Ops) but the emergency center is typically headed by a Colonel-rank officer supported by a handful of lower-ranking officers and enlisted personnel. In a couple minutes of work they would translate the president’s orders into a

launch order and using multiple means of communications transmit it directly to the executing submarine, land missile and bomber crews. Senior generals such as the 4-star head of Strategic Command would receive the launch order at the same time as the executing commanders, and would not have time to effectively intervene to stop the rapid execution (2 minutes later in the case of land missile crews)even if they wanted to do so in defiance of the president’s wishes.

The same story holds in the case of alternative “war rooms” such as Strategic Command’s where a duty team of relatively low rank headed by a Colonel might be required to perform this function if the Pentagon cannot or does not. Indeed, the Colonel duty commander might be called upon to give the initial briefing of the president in some circumstances in which the 4-star general in nominal charge is temporarily out of touch. In short, the president’s orders flow through military entities quickly and the role of general officers in the implementation process is circumscribed and inessential.

2. As for the Russian diagram, essential reading is the testimony of the then leading Russian NC3 expert before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee (chaired by Sen. Biden) just a few weeks after the Moscow coup of 1991. This Russian Colonel in the Strategic Rocket Forces was described to me by President Gorbachev’s senior advisor (Evgeny Velikhov)as the person with the deepest knowledge of the Russian nuclear release and safeguards arrangements at the time. He provides fascinating and authoritative details of the role of the key civilian and military leaders in directing the use of Russian nuclear weapons. See Command and Control of Soviet Nuclear Weapons: Dangers and Opportunities Arising from the August Revolution, Hearing before the Subcommittee on European Affairs, Committee on Foreign Relations, September 24, 1991 (U.S. GPO, 1992).

3. My own proposal for restructuring NC3 and adopting a policy of “no immediate second use” in order to increase presidential decision time and address the conditions that created the problems raised by the current sole authority arrangement was first developed in my Strategic Command and Control (Brookings, 1985). The fundamental challenge is to revamp the NC3 system to ensure its survivability and extend its duration from the current time period measured in minutes to a period measured in weeks and months, which is the endurance of the U.S. strategic submarine force. This would entail massive investment, well beyond the current modernization programming. It may be “radical”, as Wellerstein characterizes it, but it is conceptually aligned with the traditional strategy of deterrence based on survivable forces and command systems capable of withstanding a massive attack and providing the means for a devastating response. We failed to deploy such a resilient NC3 system, and “adapted” to this acute vulnerability by instituting the quick-launch sole authority launch protocol and by pre-delegating nuclear launch authority to the military throughout the Cold War (revoked after the end of the Cold War but its revival is being considered today) If my proposal is radical, then so is mainstream deterrence theory.

There are so many varied interpretations of British (UK) nuclear control. Some say the Captain of the Vanguard/future Dreadnought SSBN has full launch control – UK never had a PAL system. Some say the PM alone has full oversight – there is not Deputy PM or Cabinet member to verify. Some same the Chief of Defence Staff must verify and can veto. Others even say the Queen, formal head of the armed forces, can even stop or authorise.