SHIN YOUNG-JEON

NOVEMBER 2, 2021

I. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, Shin Young-jeon assesses the potential for the Northeast Asian Public Health Initiative (NEAPHI) to contribute to Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR+) given the COVID-19 situation in the DPRK and the operational status, limitations, and future challenges that NEAPHI must address.

Young-jeon Shin is a professor at the Hanyang University School of Medicine. He is a steering committee member of the Academy of Critical Health Policy, the Korean Society for Preventative Medicine, and the editor-in-chief for Health and Social Welfare Review. He has been serving as an advisor to the Ministry of Unification and the Ministry of Health and Welfare for a long time in the health care sector of the ROK and the DPRK.

Acknowledgements: This paper was presented at the Cooperative Solutions for North Korean Denuclearization Workshops, September 2021, organized by the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (APLN). The workshops were sponsored by the ROK Ministry of Unification and the MacArthur Foundation, and supported by the Nuclear Threat Initiative as part of an APLN project on reviewing the potential for an effective Cooperative Threat Reduction plus (CTR+) proposal for the DPRK. It is published by APLN here. The slides presentation is here and a video of the presentation may be viewed here

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

This report is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here.

Banner image: ROK Ministry of Foreign Affairs, NEAPHI virtual meeting, August 31, 2021, here

II. NAPSNET SPECIAL REPORT BY SHIN YOUNG-JEON

INTER-KOREAN SOLIDARITY AROUND COVID-19, UNDER THE NORTHEAST ASIAN PUBLIC HEALTH INITIATIVE (NEAPHI), AS A CONTRIBUTION TO COOPERATIVE THREAT REDUCTION (CTR+)

NOVEMBER 2, 2021

1. Introduction

Although the DPRK still says that no COVID-19 cases have occurred in the country (as of mid-October 2021), they are currently suffering from the “triple hardship” of 1) strong economic sanctions against the country, 2) prolonged border closures due to COVID-19, and 3) the COVID-19 epidemic itself.

Notwithstanding the new Biden administration, DPRK-US dialogue has not progressed. In the DPRK, warning signs of humanitarian issues (i.e., food and health) have recently appeared. More specifically, 17 percent of the population under five years old are undernourished.[1] At the end of July 2021, the DPRK imported medicines (insulin, antibiotics, etc.) worth about $3 million from China. This import suggests that there is a shortage of essential medicines in the DPRK.

In a situation where dialogue between the two Koreas has been halted, ROK President Moon Jae-in recently proposed on several occasions the creation of a “Northeast Asian Public Health Initiative (NEAPHI).” Currently, the ROK, the United States, China, Russia, Mongolia, and Japan have joined in NEAPHI dialogues, but the DPRK has yet to participate. This essay will examine the current operational status, implications, limitations, and future challenges that NEAPHI must meet to be successful. A program such as NEAPHI may also be critical to achieving “hard” security with the DPRK as a form of Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) that is integral to the realization of the Korean Peninsula’s denuclearization.

2. The DPRK’s COVID-19 outbreak and its response

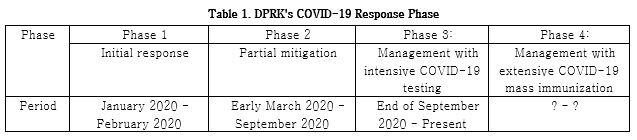

Currently, the DPRK’s COVID-19 response has reached its 3rd phase. About 1,400-1,500 COVID-19 tests are conducted every week, and the situation appears to be under control to some extent. However, it has not yet entered the management stage with extensive COVID-19 mass immunization.

The DPRK applied for participation in the COVAX Facility from the beginning but did not respond to the COVAX Facility’s offer to supply 1.9 million doses of AstraZeneca (AZ) vaccine earlier this year. In response to the recent offer made to allocate 2.97 million doses of the Chinese-made COVID-19 vaccine to the DPRK, the DPRK refused support in early September, stating that “the 2.97 million doses being offered to DPR Korea by COVAX may be relocated to severely affected countries.”[2]

It seems that the DPRK rejected vaccines offered by the COVAX Facility due to the following reasons: 1) vaccination of less than 20 million people (<80%) is not effective in preventing the COVID-19 epidemic, 2) it prefers vaccines from other companies, and 3) the external propaganda purpose of “We have no problems.” In conclusion, DPRK has not yet entered phase 4, mass immunization against COVID-19.

3. Northeast Asian Public Health Initiative (NEAPHI)

Background for proposing NEAPHI

“I propose today launching a Northeast Asia Cooperation Initiative for Infectious Disease Control and Public Health, whereby North Korea participates as a member along with China, Japan, Mongolia and the Republic of Korea. A cooperative architecture that guarantees collective protection of life and safety will lay the groundwork for North Korea to have its security guaranteed by engaging with the international community.”

–President Moon Jae-in, 75th UN General Assembly Keynote Speech (September 22, 2020, New York)

With inter-Korean dialogue suspended for a long time, President Moon Jae-in proposed NEAPHI for the following reasons:

First, there have been discussions and projects on Northeast Asian cooperation in various fields for a long time, such as Northeast Asia Ecological Network, Life Community on the Korean Peninsula, Tumen River Forum, and Mongolia International Tuberculosis Conference. The need for a Northeast Asian cooperation body has been raised in the health and medical field as well.[3]

Second, the health sector is the most non-political. As shown in examples such as malaria, bird flu, African swine fever (ASF), and forest festivals, the health sector is an area where mutual cooperation between the two Koreas would be particularly useful. In addition, on September 19, 2018, the leaders of the two Koreas agreed to exchange information and cooperate on the issue of infectious diseases. The Moon Jae-in government seems to have decided that it would be relatively easy to resume communication through health sector cooperation that the two leaders had previously already agreed on.

Third, in order for the DPRK to open its borders and resume trade and tourism, inter-Korean cooperation in the health and quarantine sectors is required.

Finally, it is believed to be an attempt to make progress through a multilateral approach in a situation where bilateral dialogue between the two Koreas is difficult.

NEAPHI’s activities

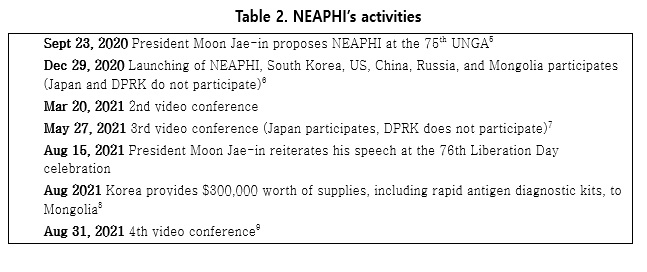

Since its launch on December 29, 2020, NEAPHI has held four video conferences. It initially started with five countries including South Korea, the United States, China, Russia, and Mongolia, but Japan participated from the third meeting in May 2021, and the initiative then consisted of a total of six countries. Through NEAPHI, Korea provided $300,000 worth of supplies, including rapid antigen diagnostic kits, to Mongolia.

On August 15, 2021, at the 76th Liberation Day celebration, President Moon Jae-in said, “NEAPHI is currently discussing cooperative projects such as information sharing, joint stockpiling of medical quarantine supplies, and joint training of COVID-19 response personnel.”[4] However, the DPRK has yet to participate.

Implications of NEAPHI

Despite its limited achievements, NEAPHI currently has the following implications. First, it is a paradigm shift in security. The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that a public health problem can do more than nuclear weapons in seriously harming human survival. Through the COVID-19 pandemic situation, the hostile conventional security paradigm has shifted to a situation in which each country must cooperate to protect its security and safety. Second, the current COVID-19 pandemic has shown that economic growth is impossible without the establishment of a strong public health system. Third, under the pandemic, international cooperation is necessary. In the words of Gro Harlem Brundtland, former Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), “We are swimming in a single micro-bacterial pool.” Malaria, avian flu, African swine fever, etc. cannot be tackled alone. In particular, cooperation with neighboring countries that share borders is essential.

In this regard, NEAPHI presents a new path for the ROK and the DPRK on the Korean Peninsula. In particular, NEAPHI’s importance has grown since the Korea-US summit in May. The Korea-US summit agreement contains the following:

“Together, the United States and the Republic of Korea will: Support the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) as steering group members, to improve global capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease threats. … To facilitate this the ROK has committed $200 million in new funding over five years to help address future health threats.”

The Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) is an international solidarity organization launched in February 2014 to cope with global health threats from infectious diseases. It was initially launched with 44 countries, but as of June 2021, 70 countries are participating.

However, the GHSA excludes China’s participation and consists only of US allies, raising concerns that the United States is attempting to use public health as a “weapon” in the international community. Moreover, many experts are concerned that the GHSA could undermine the role of the current WHO. With China excluded, the GHSA is unlikely to operate successfully, and it will be difficult for Korea, which is geographically adjacent to China, to play an active role.[10] To dispel these concerns, the successful operation of NEAPHI, in which the US as well as China and Russia are involved, is necessary. It also provides a reason for the DPRK to participate in NEAPHI.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite the various positive meanings of NEAPHI, it currently has the following problems. First, in order to induce the DPRK’s participation, large-scale project proposals such as COVID-19 vaccine support for 25 million North Koreans are needed, and a stable funding mechanism must be prepared. Second, conditions should be created for China, Russia, and Mongolia to play a more active role. Third, it is necessary to develop a strategic plan that divides and differentiates roles with existing international organizations and NGOs. Finally, current NEAPHI work in South Korea is supervised by a manager from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—their expertise and authority are too weak to successfully perform the aforementioned tasks.

4. Closing Remarks

The “triple hardship” that North Korean society is experiencing can only be resolved through multilateral cooperation between the two Koreas, China, the United States, Russia, and Japan. If such international cooperation does not successfully take place, it is highly likely that disasters such as the war crisis and the great famine of the 1990s will recur on the Korean Peninsula. It could also lead to a deepening of the Cold War between the US and China. In that respect, NEAPHI could be a useful platform for turning these international difficulties into opportunities for success.

III. ENDNOTES

[1] DPRK, “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Voluntary National Review on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda,” The United Nations, June, 2021.

[2] VOA. N. Korea Rejects COVID Vaccines, Saying Hard-hit Nations Have Greater Need. (2021) accessed October 21, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/covid-19-pandemic_n-korea-rejects-covid-vaccines-saying-hard-hit-nations-have-greater-need/6210242.html

[3] An example is the establishment and operation of ACEF (Asia Children’ Fund), where major Asian countries are responsible for the health of Asian children (Shin, 2018).

[4] Moon, Jae-in. “Address by President Moon Jae-in on Korea’s 76th Liberation Day.” (2021), accessed October 21, 2021, https://english1.president.go.kr/Briefingspeeches/Speeches/1045

[5] Moon, Jae-in. “Address by President Moon Jae-in at 75th Session of United Nations General Assembly.” The Republic of Korea Cheong Wa Dae, September 23, 2020. https://english1.president.go.kr/Briefingspeeches/Speeches/881

[6] MFA. “Launching Track 1.5 of Neaphi.” (2020), accessed October 21, 2021, https://www.mofa.go.kr/www/brd/m_4076/view.do?seq=368771

[7] This link includes a summary of the dialogue at this event: MFA. “3rd video conference of the NEAPHI” (2021), accessed October 21, 2021, https://www.mofa.go.kr/www/brd/m_4080/view.do?seq=371214

[8] MFA. “Pilot Operation of the NEAPHI” (2021), accessed October 21, 2021. https://www.mofa.go.kr/www/brd/m_4080/view.do?seq=371441

[9] This link includes a summary of the dialogue at this event: MFA. “4th video conference of the NEAPHI” (2021), accessed October 21, 2021, https://www.mofa.go.kr/www/brd/m_4080/view.do?seq=371484

[10] Shin, Y.-J. (2021). The DPRK’s COVID-19 Outbreak and Its Response. Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 4(sup1), 320-341, at: https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2021.1906592

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent