RAKESH SOOD

SEPEMBER 26 2021

I. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, Rakesh Sood reviews India-Pakistan nuclear dynamics during crises since 1980s and outlines steps that can be taken, unilaterally, bilaterally, and globally, to lengthen the nuclear fuse and to ensure that the nuclear threshold is not crossed.

Rakesh Sood is a former Indian diplomat, columnist, writer and expert on foreign affairs and member of APLN.

This paper was presented to Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) in the Asia-Pacific Workshop, December 1-4, 2020, Asia Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament and published by APLN here The workshop was funded by the Asia Research Fund (Seoul).

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

This report is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here.

Banner image: left Indian Agni missile test June 28 2020, DRDO image; right Pakistani Ghaznavi missile test, January 23, 2020, ISPR image.

II. NAPSNET SPECIAL REPORT BY RAKESH SOOD

INDIA-PAKISTAN NUCLEAR DYNAMICS

SEPTEMBER 26 2021

Introduction

The long-standing conflict between India and Pakistan took on a sharper edge with wider regional and even global implications when both countries announced their emergence as nuclear weapon states in 1998. Any expectations that this would lower tensions were soon belied. The nuclear discourse has been dominated by Western analysts. And, since both the Indian and Pakistani strategic communities were familiar with it, it provided the dominant framework for understanding the new nuclear relationship. It made dialogue easier even though the underlying politics and geography bore little resemblance to the ideology-driven Cold War-world. For Pakistan, the Western attribution that the India-Pakistan theater was a “nuclear flashpoint” was also politically convenient as it kept Western attention focused on Kashmir.

This paper seeks to unpack the India-Pakistan nuclear dynamics by taking an empirical look at the different crises beginning from the late 1980s. The first section deals with the origins of the India-Pakistan conflict and how the changing internal political dynamics have influenced and shaped the nuclear dynamic. The second section compares the nuclear doctrines of both countries as well as the current nuclear capabilities and future plans for their nuclear arsenals. Since neither country has released official figures about its arsenal, the estimates of capabilities are drawn from the Global Nuclear Database published by the U.S.‒based Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. The third section covers the numerous crises since the late 1980s with relevant references to domestic political drivers. Two of these pertain to the pre-1998 and the rest to the post-1998 period. The fourth section shows the role of external actors and how India and Pakistan drew different conclusions from the crises. The fifth and final section concludes the essay by outlining steps that can be taken, unilaterally, bilaterally, and globally, to lengthen the nuclear fuse and to ensure that the nuclear threshold is not crossed.

One could certainly suggest unilateral measures that, on the one hand, India could take to restore normalcy in the state of Jammu and Kashmir or, on the other, that the civilian government in Pakistan could take to reduce the role of the military in policymaking. However, these are beyond the scope of this paper as they entail taking a deep dive into domestic politics of both countries. In any case, the prospect that either would take such actions in current times are about as likely as global elimination of nuclear weapons. This paper accordingly focuses on the more realistic scenario, based on the assumption of continued hostile relations between the two neighbors, but also on the assumption that there is a shared convergence in seeking to prevent inadvertent escalation that might lead to unintended consequences and, ultimately, to nuclear war.

1. Origins of a troubled relationship

India and Pakistan have been locked into a conflictual relationship since they both became independent in 1947, arising out of the partition of British India. The British rulers divided India, creating Pakistan as a separate homeland for the Muslims of the Indian sub-continent, on the grounds that Hindus and Muslims constituted two separate nations—the concept of the “two nation theory.”[1] Within months, India and Pakistan were locked in a conflict over the state of Jammu and Kashmir, which had legally acceded to India but was claimed by Pakistan on the grounds that it was a Muslim majority state. After four inconclusive wars in 1947-48, 1965, 1971, and 1999, the state of Jammu and Kashmir remains a disputed territory with India in possession of roughly two-thirds of the erstwhile state and the remaining under the control of Pakistan. The 740 km boundary in the state of Jammu and Kashmir is called the Line of Control, while the remaining 2,400 km border between the two countries is the “international boundary,” which is not disputed.

Today, however, it is clear that Kashmir is not the only source of conflict. Nor can the conflict be explained in terms of a continuation of the “two nation theory” because there are more than 170 million Muslims in India accounting for 14.2 percent of India’s population, up from less than 10 percent in 1951. In comparison, Pakistan’s population is 210 million; Hindus account for less than 2 percent of its population, down from 12 percent in 1951 because many Pakistan Hindus, finding themselves reduced to second class citizens, have either converted or migrated. Moreover, when the glue of religion proved unable to hold East Pakistan and West Pakistan together, leading to its eastern wing emerging as Bangladesh in 1971 after a brutal suppression widely described as “genocide,” the “two nation theory” was unambiguously controverted.[2]

As a new state, Pakistan consciously turned its back on its sub-continental civilizational roots that it shared with India and sought to redefine its identity anew, in the name of Islam. However, Pakistan found it difficult to reconcile the notion of a modern state with its founding ideology. The Muslim clergy represented by Jamaat e Islami, led by Maulana Maudoodi, had an uneasy relationship with the Muslim League, the political party led by Mohammed Ali Jinnah that had spearheaded the call for a separate homeland of the Muslims of the Indian sub-continent. The clergy suspected the League of using religion for political ends while actually desiring a modern state rather than one based on Islamic law (shariah). The desire for a national identity rooted in religion became the first source of divergence with India whose leaders sought to create a secular, plural, and democratic state.

The second source of divergence came with the decline of political parties in Pakistan, leading to long periods of military dictatorship. From 1958 to 1971, from 1977 to 1988, and from 1999 to 2008, Pakistan was under army rule, taking its toll on political parties and weakening institutions like the judiciary and media. Even with the restoration of democracy in 2008, the military still plays a leading role, especially where security, defence, and foreign policy are concerned. Repeated involvement of the military in governance has led to a militarization of the state. Perpetuating a hostile relationship with India has become necessary for the military to retain its role in the country’s political life.

Further, like authoritarian rulers in other countries, the military rulers often sought to legitimize their coups by presenting themselves as defenders of not just the frontiers of the state but also guardians of Pakistan’s Islamic ideology. The military rulers relied on the street power of the mullahs (Islamic religious leaders), a technique that was effectively used by General Zia ul Haq. It cast the hostility with India into a “jihad,” a fight between the Muslim and the infidel, deepening the divide. Defining an identity by negating its subcontinental civilizational roots and making it “non-Indian” has remained Pakistan’s dilemma. The military-mosque nexus shifted it from non-Indian to “anti-Indian,” changing the historical narrative and locking not just the state but also the people into a relationship of hostility.[3]

On 6 February 2020, Pakistan’s retired military officer, Lt. Gen Khalid Kidwai (who headed the Strategic Plans Division or SPD from 2000 to 2013 and is an adviser to Pakistan’s Nuclear Command Authority) spoke at the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London on strategic stability. He identified four drivers of Indian policy as Hindutva philosophy, seeking to erase the “sense of humiliation of a Hindu nation of a thousand years of Muslim rule;” restoration of the perceived glory of Hindu India, going back to 300 BC; India’s “quest for regional domination,” particularly in relation to Pakistan; and finally, a “self-delusional one way competition with China,” by aligning with the United States as an Indo-Pacific power.[4] Lt. Gen (retd) Kidwai’s thinking is not new; it is reflected in official military writings in Pakistani training institutions and has played a major role in defining Pakistan military’s strategic culture. It is therefore unsurprising that the army felt threatened by, and quickly stymied the few attempts by elected civilian leaders to improve relations with India (by Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto in 1989 and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in 1999).

Four key themes may be identified in the Pakistani military’s strategic culture, of which three directly affect its relationship with India and the fourth does so indirectly. First, the Pakistani army considers the partition to have been an unfair process and therefore it considers it “incomplete.” This view explains their obsession with Kashmir as well as the role of the army as the “guardian of Pakistan’s ideological frontiers.” Linked to this factor is the conviction that India remains implacably opposed to the “two nation theory,” has never accepted partition, and does not accept the existence of an independent, sovereign Pakistan. Proof of this proposition to the Pakistani military is India’s role in the 1971 war that led to the break-up of Pakistan, with East Pakistan seceding to declare itself as independent Bangladesh. The third theme is that India is a hegemon and poses an existential threat to Pakistan because it seeks to impose a regional security and economic structure on South Asia with the goal of converting its smaller neighbors into satellite states. In their view, such Indian ambitions must be thwarted. The fourth theme has to do with Afghanistan, which has never accepted the Durand Line as the border with Pakistan. In the past, Pakistan sought “strategic depth” in Afghanistan. It has become increasingly paranoid about Indian presence in Afghanistan and the possibility of collusion between India and Afghanistan to destabilize Pakistan’s Pashtun and Baloch borderlands.[5]

Pakistan has sought to compensate for its disparity with India in terms of size, population, and economy by resorting to asymmetric warfare and seeking alliances. Having been a frontline state in the United States’ covert war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) successfully weaponised “jihad” as the instrument to radicalize groups to undertake terrorist strikes and low-intensity conflict. Pakistan was no stranger to asymmetric warfare, having previously supported insurgencies in India that included the Naga insurgency from East Pakistan in the 1960s, Sikh militancy in the 1980s, and, since 1990, by waging a proxy war through the training, equipping, and infiltration of terrorists into Kashmir in the name of “jihad.”

During the Cold War, Pakistan was a member of two U.S.‒led military alliances—SEATO (South East Asia Treaty Organisation)[6] and CENTO (Central Treaty Organisation).[7] Since the 9/11 attacks in the United States in 2001, after which the United States and other countries became more concerned with the global implications of jihadi terrorism, Pakistan has strengthened its ties with China. In addition to the cooperation in conventional, nuclear, and missile sectors, China has also emerged as by far the largest source of foreign investment in Pakistan. The strategic underpinning between the two is apparent since India and China have an unresolved boundary dispute and fought a war in 1962. In 2020 the situation worsened, leading to clashes between these two great powers that caused casualties for the first time in 45 years.

In May 1998, both India and Pakistan conducted a series of nuclear tests, declaring themselves nuclear weapon states and adding a new dimension to their hostile relationship. Many would argue that the nuclear shadow over the relationship existed even earlier. Some would go back to January 1972 when, after the creation of Bangladesh, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto convened Pakistan’s nuclear scientists exhorting them that the only guarantee for ensuring Pakistan’s territorial integrity was to develop nuclear weapons. Or, even earlier after the unsuccessful 1965 war when he famously declared “we will eat grass if we have to, we will make the nuclear bomb.”[8] Others would link the nuclear shadow to India undertaking a peaceful nuclear explosion (PNE) in 1974, or the U.S. attempt at coercive nuclear diplomacy by bringing in the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal during the 1971 war, or even earlier to 1964, when China announced its entry onto the world’s nuclear stage, after having inflicted a humiliating defeat on India in the border conflict in 1962.[9]

The India-Pakistan nuclear rivalry is just another dimension of the more deep-seated hostility between the two countries. What this hostility means is that resolving the Kashmir conflict would not normalize the relationship because Pakistan sees India as an existential threat and this perception is not going to change easily, certainly not as long as the military continues to dominate its security and foreign policymaking, and perhaps even beyond that because a new historical narrative has taken root in Pakistan. Some of the recent Hindutva-tinted rhetoric from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India only serves to convince the Pakistan military that India’s secularism was always a sham and that it is just a matter of time until the liberal-secular urban elite in India will be marginalized and yield to the majoritarian Hindu impulse.

2. Evolving nuclear doctrines

The only use of nuclear weapons occurred when the United States was the sole possessor of nuclear weapons. By the time the former Soviet Union exploded its nuclear device in 1949, the Cold War had already begun, as reflected by the division of Germany and Europe into East and West. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), a U.S.-led military alliance for the defence of Western Europe, was created in 1949 and a Soviet-led Warsaw Pact came into being in 1955 following West Germany’s induction into NATO in 1953. The United States and the former Soviet Union were soon locked into a qualitative and quantitative nuclear arms race. This political, economic, and military competition based on the threat of nuclear annihilation between two nuclear superpowers has shaped the growth of a nuclear theology.The nature of warfare changed fundamentally when the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, followed by a second attack on Nagasaki three days later. It was clear then that the sheer destructive power of nuclear weapons was qualitatively different from any other weapon system. This remains true today. The biggest conventional bomb is the GBU Massive Ordnance Air Blast with an explosive yield of 11 tonnes of TNT equivalent; in comparison, the Hiroshima bomb was 15 kilotons (kt) or 15,000 tonnes. Today, the nuclear arsenals of many states contain weapons with yields in the megaton range and even the tactical nuclear weapons have yields of 0.5 kt or more. This realization contributed to the nuclear taboo, a term referring to the moral force behind the fact that nuclear weapons have not been used since 1945. though there were numerous instances during the Cold War when the taboo was close to being breached.

Two schools of deterrence theory soon emerged in the United States. One was led by Bernard Brodie, a political science professor who had served at the U.S. Department of the Navy during World War II and later spent nearly two decades at RAND Corporation. Brodie held that deterrence is automatic and ensured through retaliation because the one who initiates the nuclear attack cannot be certain that the adversary’s entire nuclear arsenal has been eliminated. The following idea is attributed to Brodie: “Thus far the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on, its chief purpose must be to avert them. It can have almost no other purpose.”

The other school was led by Albert Wohlstetter, a mathematics major with a strong focus on modelling economic and business cycles, who had worked at the U.S. War Production Board during World War II and who, like Brodie, later moved to RAND. Although he too believed in massive retaliation, he felt that ensuring second strike capability needed larger arsenals and survivability to prevent a nuclear Pearl Harbor. He used modelling studies based on weapon yields, bomber ranges, accuracies and reliabilities of systems, and blast resistance in what became the classic basing studies for the U.S. Strategic Air Command. For Brodie, the risk of retaliation was an adequate deterrent while for Wohlstetter, it was the certainty of retaliation with large numbers that was necessary for deterrence to work. Given that the nuclear arms race led to the two nuclear superpowers accumulating more than 65,000 nuclear weapons at its peak, it is clear that Wohlstetter carried the day.[10]

Acceptance of Wohlstetter’s approach gave rise to new concepts of flexible response, escalation dominance, countervalue and counterforce, survivability, compellence and “prevalence” (implying an extension of compellence when deterrence has broken down, by ensuring control of limited use at each step to prevail). It is counterfactual to enquire whether this conceptual evolution contributed to a stable deterrence posture between the United States and its allies on the one hand, and the former Soviet Union on the other. It certainly ensured, however, that the nuclear arms race continued because the two countries were engaged in an all-out rivalry in political, economic, and conventional and nuclear military dimensions. During the best documented nuclear crisis, that is, the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, the United States had an arsenal of 25,540 bombs whereas the former Soviet Union had only 3,346. Despite this imbalance, deterrence clearly worked. It nevertheless established the ground rule of mutual vulnerability as the basis for deterrence. As the former Soviet Union achieved numerical equivalence in its arsenal, the concept of managing the nuclear arms race by introducing equivalent strategic capabilities through arms control gained prominence.

Deterrence stability was underwritten by “parity” and “mutual vulnerability.” The latter was codified by the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. Eventually, the United States withdrew from the ABM Treaty in 2002. But for most of the Cold War, the two nuclear superpowers sought to restrain the nuclear arms race and to preserve strategic stability through arms control agreements like SALT, START, and INF, the last in the sequence being New START in 2010. Finally, they tried to manage crises through hotlines, nuclear risk reduction centers, and early warning systems. It is important to recall that during the 1970s and 1980s, nuclear stability did not appear to be assured and many believed the Cold War was unlikely to end peacefully or that the nuclear taboo would last as long as it has. Documents declassified after the end of the Cold War also indicate there were some tense occasions, some inadvertent, and some a result of misperception arising out of system glitches. In these cases, it was pure luck, and not arms control measures, that ensured that nuclear weapons were not launched. The trinity of deterrence stability, arms race stability, and crisis management stability formed the vocabulary of nuclear arms control, the essence of the nuclear theology referred to above.

The prism of U.S.‒Soviet bipolarity, however, does not help much in understanding Indian and Pakistani nuclear doctrines and their mutual security crises, although Western analysts tend to view it through this prism. The key difference is that the United States and former Soviet Union reflected a degree of symmetry in terms of their arsenals and doctrinal approaches, relying on mutual vulnerability and assured second strike capability, once the Soviet Union had caught up with the United States. Further, given their position as nuclear superpowers, it was possible to look at the United States‒Soviet Union equation as a standalone nuclear dyad. In contrast, the India‒Pakistan relationship is marked by asymmetry in terms of doctrinal approaches, as elaborated below. Secondly, since India declared itself a nuclear weapon state in 1998, it has maintained that its capability was intended as a deterrent against both Pakistan and China whereas Pakistan defines its capability as India-specific. Given these differences, it is not possible to see the India-Pakistan equation in terms of a dyad.

The geopolitical shift from Euro-Atlantic to the Indo-Pacific also shows the presence of many more nuclear actors in an increasingly crowded geopolitical space. It includes the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the return of major power rivalry, with the United States, Russia, and China added into the mix of multiple rivalry equations as well as the United States’ treaty allies—Japan and South Korea. The region therefore hosts multiple nuclear dyads, but each dyad may be linked to other nuclear actors, creating a loosely linked “nuclear chain.” The creation of a nuclear chain has made the search for nuclear stability in today’s world more elusive at a time when the old arms control agreements are being discarded in response to changing political realities.

India first laid out the elements of its nuclear doctrine in a paper titled “Evolution of India’s Nuclear Policy,” tabled by then Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee in parliament shortly after the 1998 nuclear tests. The paper made it clear that India did not see nuclear weapons as weapons of war fighting, but in a more limited role, intended to address nuclear threats through deterrence. The prime minister’s speech and the paper were followed by another draft paper prepared by a newly constituted National Security Advisory Board and circulated in 1999 to elicit wider discussion. A more succinct and authoritative text was released in 2003 following a meeting of the Cabinet Committee on Security.[11] The key elements of the doctrine were:

- Building and maintaining a credible minimum deterrent, based on a triad that includes land-based, sea-based, and airborne delivery systems.

- Sustaining a posture of nuclear no-first-use vis-à-vis nuclear armed states and non-use of nuclear weapons vis-à-vis non-nuclear weapon states.

- Ensuring nuclear retaliation in response to a nuclear attack on Indian territory or on Indian forces anywhere, inflicting massive and unacceptable damage.

- Retaining the option of nuclear retaliation in response to a chemical or biological weapons attack.

- Continuing the moratorium on nuclear explosive testing.

- Remaining ready to join Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty negotiations.

- Ensuring strict export controls on nuclear and missile-related materials and technologies.

- Continuing commitment to the goal of a nuclear weapons-free world through global, verifiable, and non-discriminatory nuclear disarmament.

Since India’s doctrine makes clear that its nuclear weapons are only to deter a nuclear threat or attack, India needs additional capabilities to deal with threats of sub-conventional and conventional conflicts. By eschewing a warfighting role for nuclear weapons, India is able to duck the temptations of a nuclear arms race with Pakistan or China. Given the short distances between India and these two potential adversaries that compress time available for decision-making, India believes that it is not possible to make a distinction between “tactical” and “strategic” nuclear weapons or their use. This reflects another departure from the United States‒Soviet approaches that provided a 25-minute interval for a missile launched from the mainland to reach a target on the adversary’s mainland. In the U.S.‒Soviet arms control vocabulary, long-range vectors were considered “strategic” and systems with ranges below 5,500 km were further divided into intermediate, medium, and short-range systems. Extended deterrence assurances to allies in Europe and Asia also introduced political compulsions for forward deployment of U.S. and Soviet weapons that were attributed tactical or battlefield roles. Such distinctions undoubtedly contributed to the arms race but do not exist in South Asia.

Pakistan has chosen to give its nuclear weapons a different role. It prefers to retain a degree of ambiguity claiming that it strengthens deterrence while maintaining that its nuclear capability is India-specific, and, consequently, its size will be determined by India’s arsenal. Although Pakistan states that it maintains a minimum credible deterrent (sometimes also called a minimum defensive deterrent), its role is not just to deter nuclear use by India but also to act as an equalizer against India’s conventional superiority. Pakistan therefore rejects the idea of a no-first-use policy. In 2002, it had first declared “four red lines that could trigger a nuclear response: occupation of a large part of Pakistan territory by India, destruction of a large part of Pakistan’s military capacity, attempt to strangulate Pakistan’s economy, and creating political destabilization.”[12]

Pakistan’s doctrine has since evolved to “full spectrum deterrence” as Pakistan has added short- range nuclear armed systems for tactical use (60 km range Hatf IX or Nasr ballistic missile) and is also adding a number of cruise missile systems with dual capability. The Nasr was flight tested in 2011 and, according to a statement by the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) Directorate,[13] it “adds deterrence value to Pakistan’s Strategic Weapons Development Programme at shorter ranges.” The Nasr could carry “nuclear warheads of appropriate yield with high accuracy” and is a quick response system with shoot and scoot capabilities (which can fire and then quickly relocate). According to Lt. Gen (retd) Kidwai, Pakistan’s range of nuclear weapons provide “full spectrum deterrence, including at strategic, operational, and tactical levels.” By deliberately lowering the nuclear threshold, Pakistan believes it strengthens deterrence and as Lt. Gen (retd) Kidwai explains “it is the Full Spectrum Deterrence capability of Pakistan that brings the international community rushing into South Asia to prevent a wider conflagration.”[14]

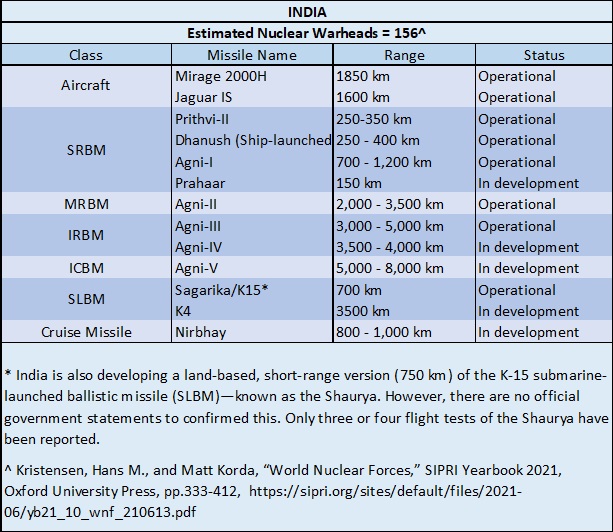

Neither India nor Pakistan have made any official statements regarding the sizes of their nuclear arsenals. Analysts are therefore left to derive estimates based on fissile material production capacities, occasional press releases about missile launches, and other indicators about likely inductions of new delivery systems. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s database on World Nuclear Forces, India is estimated to have produced approximately 156 warheads by January 2021.[15] These are currently distributed over seven delivery platforms and increasing at the rate of about ten warheads every year. The delivery platforms include two aircraft (Mirage 2000 and Jaguar, both originally deployed in the 1980s), four land-based ballistic missiles (Prithvi II, Agni I, Agni II, and Agni III, each capable of carrying a single warhead with ranges from 350 km to 3,000 kms) and one submarine-launched ballistic missile (K-15 Sagarika with a range of 700 kms) for its nuclear-powered submarines (SSBN). Given these ranges, the Indian triad is still an exercise in the making.

India’s stockpile of weapons-grade plutonium (its arsenal is entirely plutonium-based) is considered adequate for 200 warheads, but plutonium production could increase depending on how its Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor project develops.[16] The Indian land-based missile program was launched in the mid-1980s but the Prithvi II was inducted only in 2003. The Agni-series of land-based missiles are solid-fuelled systems and road or rail-mobile. Two land-based systems, Agni IV and Agni V, are currently under development with ranges of 4,000 and 5,000 km respectively. There is speculation that Agni V may carry Multiple Independently-targetable Re-entry Vehicles (MIRVs), but it would mean reducing range and, unless China develops a missile defence system, there would be little military need for MIRVs on Agni V. MIRVs may become more likely once India develops missiles with ranges over 8,000 km. The indigenous SSBN programme has suffered long delays and only one SSBN has completed sea trials. Another SSBN is expected to be commissioned next year and India is likely to build three or four more SSBNs. The K-15 has a limited range of 700 km. Such a short range only enables India to target southern Pakistan. To target coastal China, the submarine would need to get to South China Sea. Another SLBM K-4 with a range of 3,500 km is being tested and will eventually replace the K-15. India is also developing a ground-launched cruise missile that was finally flight-tested up to 700 km in 2017 after numerous failures. There are rumours that this missile may be dual-capable (it can serve in both conventional and nuclear roles) though there are no official statements to indicate this.

Table 1: India’s Nuclear Forces

Source: SIPRI; Bulletin of Atomic Scientists; Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

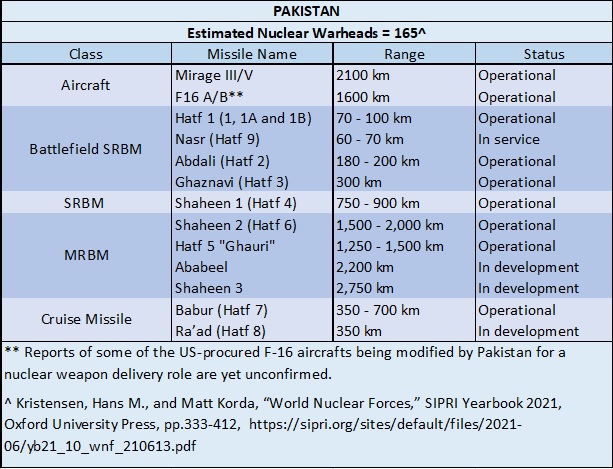

Pakistan’s nuclear stockpile is estimated at 165 warheads[17] as of January 2021, and estimated to grow to 220 to 250 warheads by 2025[18] in view of an ambitious expansion of both its uranium enrichment and plutonium production capacities. In addition to the Kahuta enrichment plant, another has been built at Gadwal, and three plutonium production reactors have been added at the Khushab complex during the last decade. In 1998, Pakistan reportedly tested both types of devices, based on highly enriched uranium and plutonium. It is estimated that Pakistan’s fissile material inventory of 3,400 kg of highly enriched (90 percent) uranium and about 280 kg of plutonium is enough to produce between 236 and 283 warheads.

Pakistan’s delivery platforms include Mirage III/V and F-16 aircraft, and there are reports that the withholding of additional aircraft supplies by the United States and France emerging as a key Indian strategic partner, Pakistan would in future rely on the JF-17, jointly developed with China for a nuclear role, possibly using Ra’ad, an air launched cruise missile. It has six operational land-based ballistic missile systems Abdali (Hatf-2) range of 200 kms, Ghaznavi (Hatf-3) range of 300 kms, Shaheen 1 (Hatf-4) range of 750 kms, Ghauri (Hatf-5) range of 1,250 kms, Shaheen 2 (Hatf-6) range of 1,500 kms, and the most recent Nasr (Hatf-9) with a range of 60 kms. All are solid-fuelled except for the Ghauri, which is liquid-fuelled and is a variant of the DPRK’s Nodong missiles that Pakistan acquired in the 1990s in exchange for sharing nuclear enrichment technology. Shaheen 1 is based on the Chinese M-9 missile supplied in the 1990s. Pakistan has also tested Shaheen 3 with a range of 2,750 kms. In 2017 it also tested Ababeel, a new missile with MIRV capability. Hatf 2,3,4, and 9 are dual-capable, in keeping with Pakistan’s policy of ambiguity, and are deployed in garrisons close to the Indian border.

Pakistan has also developed a ground launched Babur (Hatf-7) and the air-launched Ra’ad (Hatf-8), both nuclear-capable cruise missiles. Currently, efforts are underway to improve their ranges. Babur was originally tested at 350 kms. More recent tests indicate the range has been nearly doubled. Ra’ad was also deployed with a range of 350 kms, but its newer versions indicate a range of 550 kms. A sea-launched version of Babur with a range of 450 kms has been tested both from surface and underwater launch platforms. It will eventually be deployed on the diesel-electric Agosta submarines or the newer Yuan class Type 041 submarines being acquired from China.

Table 2: Pakistan’s Nuclear Forces

Source: SIPRI; Bulletin of Atomic Scientists; Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

Pakistan’s development of battlefield and dual-capable systems has generated widespread concerns. In the 2018 Threat Assessment, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Daniel Coats said, “Pakistan continues to produce nuclear weapons and develop new types of nuclear weapons, including short range tactical weapons, sea-based cruise missiles, air launched cruise missiles, and longer-range ballistic missiles. These new types of nuclear weapons will introduce new risks for escalation dynamics and security in the region.”[19] In the 2017 South Asia Strategy issued by the White House, the Trump administration had urged Pakistan to stop sheltering terrorist organizations and emphasised the need “to prevent nuclear weapons and materials from coming into the hands of terrorists.”[20] Pakistani officials have rejected these concerns indicating that Pakistani missiles are in stored separately from warheads and are only put together at the eleventh hour.

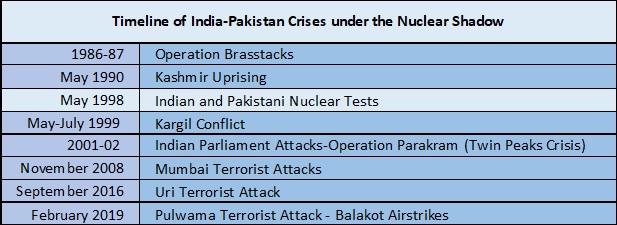

3. Crises under a nuclear shadow

Given the sources of insecurity and the doctrinal asymmetry, it is hardly surprising that India and Pakistan have very different interpretations of the crises that have raised concerns about nuclear escalation. The first case of nuclear signalling can be dated to the Operation Brasstacks crisis in 1987. India had undertaken a large-scale military exercise on the Pakistan border leading to apprehensions in Pakistan that India was preparing to launch a major attack. In late January, A. Q. Khan, widely considered the father of Pakistan’s nuclear bomb, gave a surprise interview to a visiting Indian journalist Kuldip Nayar during which he admitted that Pakistan possessed a nuclear bomb and would not hesitate to use it in case of war with India.[21] Given Khan’s high-level security clearance in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program at the time, it is reasonable to assume the interview had been cleared by the Pakistani military authorities. There is widespread conviction in Pakistani security circles that the nuclear threat worked, and India backed down. Indian observers maintain the crisis had peaked days earlier and de-escalation was under way before Khan made his statement.

The second crisis occurred in May 1990 when there was an uprising in Kashmir, and India stepped up the presence of its security forces amid rumours that Pakistan’s military might try to take advantage of the situation. Based on satellite imagery, the United States concluded that Pakistan was preparing to move its nuclear weapons and dispatched deputy national security advisor Robert Gates to Delhi and Islamabad in a bid to defuse the situation. The crisis subsided and Foreign Secretary level talks resumed the following month. Both these incidents took place before Pakistan acknowledged possession of nuclear weapons and consequently the signalling was indirect.

The situation changed after the 1998 nuclear tests and nuclear signalling became more explicit in the crises thereafter. If there was any expectation that the overt nuclear situation might bring about some stability by introducing an element of restraint, it was soon dispelled. Barely had the ink dried on the forward-looking Lahore Declaration and the related Memorandum of Understanding on nuclear confidence building measures—signed during Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee’s historic visit to Lahore in February 1999—when the Kargil conflict erupted. In a pre-emptive move, Pakistan intruded across the Line of Control (LoC) to occupy certain heights that threatened Indian access into the Ladakh region. It was a brazen attempt to alter the territorial status quo. India mounted an uphill assault and deployed the air force but in a restrained manner as the aircraft were directed not to cross the LoC. Widespread international concern at such reckless behavior and heavy casualties eventually forced Pakistan to withdraw and retreat across the LoC. It later emerged that the Pakistani political leadership had not been fully briefed about the pre-emptive move by the army generals. Growing internal differences eventually contributed to the ouster of the civilian government in a military coup in October 1999, which led to a decade of military rule. Clearly, Pakistan saw its nuclear capability as a shield under which it could seek to alter the territorial status quo, confident in its assessment that Indian retaliation would be deterred as it believed had happened in the earlier crises.

The next crisis was precipitated by an attack on the Indian parliament in December 2001 by two internationally proscribed terrorist groups based in Pakistan—Lashkar e Taiba (LeT) and Jaish e Mohammed (JeM). India responded by mobilizing its army along the border in early 2002. In an address to the nation on 12 January 2002, General Pervez Musharraf sought to defuse the situation by condemning the “terrorist attack” and announcing a ban on five jihadi organizations, including LeT and JeM. He declared that no organization would be allowed to carry out terrorist strikes within Pakistan or anywhere else. Before matters could stabilize, tensions escalated again in May when three Pakistani fedayeen (suicide attacker) attacked an army camp at Kaluchak killing 34 Indian soldiers and their family members. As Indian rhetoric sharpened, in June, General Musharraf warned that if India attacked, Pakistan retained the option of first-use of nuclear weapons. Consequently, the United States, Russia, France, Japan, and the United Kingdom engaged in active diplomacy to mediate a de-escalation of the crisis. The United States needed Pakistani military cooperation on the Pakistani-Afghan border in its war against Al Qaeda and the Taliban, and eventually tensions eased when Pakistan began to dismantle the terrorist training camps and the launch pads close to the LoC. Finally, a ceasefire across the LoC was announced in November 2003 that lasted for five years. However, according to Lt Gen (retd) Kidwai, India’s coercive exercise had failed as the Indian military had “lost the advantage of relative asymmetry in conventional forces because of Pakistan’s nuclear equalizer.”

The five-year ceasefire laid the grounds for a promising backchannel dialogue. The peace was broken in November 2008 by an audacious strike by LeT terrorists who arrived by boat and simultaneously attacked a number of targets in Mumbai. There was credible evidence that the ISI was involved in the attacks. The newly elected democratic government in Pakistan initially promised to cooperate in the investigation, even offering to send the ISI chief to India though the offer was subsequently withdrawn. It sparked a debate in India, however, about the utility of the no-first-use doctrine that was somewhat misguided because nuclear weapons were never intended to deter terrorists. That requires a different set of capabilities, which India did not possess. India therefore relied on international pressure on Pakistan since the Mumbai attack was widely seen as India’s “9/11” moment. There was strong universal condemnation of the attack, especially because foreign citizens had also been killed; at the same time India’s strategic restraint was appreciated by the international community. However, it also exposed the lack of kinetic options available to India. Nuclear strategic analysts, already unfamiliar with asymmetric nuclear dyads, were now saddled with the additional challenge of thinking through nuclear deterrence with respect to non-state actors that enjoyed covert state support.

In 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power and promised a more muscular counterterrorism policy, both domestically and against Pakistani-aided cross-border infiltration. The first incident after the current government came to power was a terrorist attack in September 2016 by four JeM fedayeen terrorists against an army brigade headquarter in Uri (in Kashmir), in which seventeen Indian soldiers were killed. Later in the month India announced that it had carried out retaliatory surgical strikes destroying the launch pads across the LoC and killing terrorists who were present there waiting to be sent across, normally done under covering fire by Pakistani forces. Pakistan denied that there were any surgical strikes, and the situation did not escalate. Prime Minister Modi successfully projected the surgical strikes as a sign of newfound Indian determination that it would not be deterred by Pakistan’s first use threat or tactical nuclear weapons. In the official briefings, it was described as “target specific, limited calibre, counter-terrorist operations across the LoC.” Clearly, the Modi government wanted to show that it was not averse to raising its coercive rhetoric. The time for “strategic restraint” that had characterized India’s approach after the Mumbai attack was over. At the diplomatic level, the SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) summit was postponed, and SAARC has been in limbo ever since.

On February 14, 2019, an Indian Kashmiri militant drove an explosive-laden SUV into a convoy transporting paramilitary forces in Pulwama (Kashmir), killing 46 troops. JeM claimed responsibility for the strike. With general elections less than two months away, the Modi government vowed retaliation. Twelve days later, Indian aircraft bombed a JeM training camp at Balakot in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. Pakistan undertook an air attack the following day and as Indian fighters scrambled, in the ensuing dogfight, an Indian pilot ejected from his damaged aircraft landing in Pakistan territory. He was returned within 48 hours with the United States, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates (UAE) claiming to have intervened to ensure safe and early return of the captured pilot. Pakistan maintained that there was no training camp at Balakot and that the Indian aircraft had dropped their ordnance on a hillside. Pakistan’s counterattack the following day showed its resolve to defend its sovereignty, and the prompt return of the captured pilot exemplified its responsible behavior. A few weeks later, both sides withdrew their High Commissioners and these positions have not been restored since.

In the official briefing the day following the Indian air strike, India’s focus was on downplaying the escalation by pointing out that it was a non-military terrorist target and a pre-emptive strike as it had advance intelligence, and the Indian operation was now terminated. The rhetoric through media channels emphasized, however, that India had called Pakistan’s nuclear bluff and created a new normal, in sharp contrast to the official briefing. Lt. Gen (retd) Kidwai maintains that this was yet another attempt by India to “induce strategic instability” and Pakistan’s calibrated response had “restored strategic stability and no new normal was allowed to prevail.” He suggests that “Pakistan has ensured seamless integration between nuclear strategy and conventional military strategy, in order to achieve the desired outcomes in the realms of peacetime deterrence, pre-war deterrence and also in intra-war deterrence.”

Table 3: Timeline of India-Pakistan Crises under the Nuclear Shadow

4. Roles of external actors

In the preceding section, seven instances were examined—two relating to the pre-1998 period, and the rest after both countries had declared themselves to be nuclear weapon states. The pre-1998 cases can be described as reflecting a situation of “recessed deterrence”—that is, as some Indian analysts stated, a form of deterrence arising from the existence of their nuclear weapons but not yet declared by the two possessor states. This posture was overtaken in 1998 when nuclear weapons began to play an explicit role. It is useful to see what lessons may be drawn from the five instances after 1998 and the role of the major powers, particularly those of the United States and China. Has anything changed over the last two decades in this regard, and if so, what?

It is possible to discern five distinct levels of conflict between India and Pakistan:

- Sub-conventional conflict or attacks by terrorist groups that are based in Pakistan and have an established modus vivendi with the Pakistani authorities, as in their attacks on the Indian parliament in 2001 or Mumbai in 2008.

- Hybrid sub-conventional conflict employing both militant groups and regular troops but trying to deny the role of the latter as in the case of Kargil in 1999.

- Conventional conflict below the nuclear threshold.

- Conventional conflict escalating to the use of tactical or battlefield nuclear weapons.

- Full-scale conflict with large scale use of nuclear weapons.

The five instances under examination fall in the first two categories. The unmistakable message to India is that possession of nuclear weapons will not deter such attacks. In each instance, India faced the challenge of finding appropriate retaliation that could combine both deterrence by denial and deterrence by punishment while keeping it below the nuclear threshold in line with its nuclear doctrine of no-first-use.

Since the Kargil crisis involved Pakistan changing the territorial status quo, the Indian objective was modest but clear—restoration of the status quo ante. In this, it had the support of the entire international community as Pakistan’s action was seen as provocative. High-level Pakistani visits by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and by Chief of Army Staff General Musharraf to Beijing to seek Chinese support elicited quiet rebuffs and provided space for the United States to play the key diplomatic role in the resolution of the crisis.

The attacks in 2001 and 2008 by Pakistan-based terrorist groups also witnessed the United States playing a diplomatic role. In the first instance, the Indian army had mobilized on the border and both armies were face-to-face. However, the United States needed Pakistan to redeploy its forces to the Pakistan-Afghan border as it had just embarked on its operations in Afghanistan after 9/11. The crisis took time to defuse until India was satisfied with Pakistani assurances that it would take action against groups like LeT and JeM. The 2008 attack in Mumbai created a dilemma for Indian decision makers. The confessions by one of the terrorists who had been captured alive and mobile telephone intercepts of conversations between the terrorists and their handlers made it evident that Pakistani authorities had been involved. The attack exposed weaknesses in India’s coastal security and was a rude reminder that it lacked appropriate kinetic options. Since the victims included nationals of other countries, however, India had to be content with international condemnation and pressure.

Pakistan concluded that it was nuclear deterrence that stymied Indian kinetic retaliation. It began to develop tactical nuclear weapons so that the space for the third category of conflict, namely conventional war below the nuclear threshold, could be constricted and that Indian kinetic retaliation would rapidly escalate matters to the fourth level, involving tactical nuclear weapons.

The Modi government that came to power in 2014 and was re-elected in 2019 sought to dispel the notion that the threat of tactical nuclear weapons would deter it from kinetic retaliation in response to a cross-border terrorist attack. According to retired military officers, India had undertaken retaliatory cross-border operations earlier in response to certain attacks but without much fanfare. This policy of “restraint” was discarded in 2017 when the Modi government declared that it had conducted “surgical strikes” across the LoC. Pakistan denied that any such attempt had been made and claimed that India had merely indulged in artillery firing across the LoC. These conflicting assertions enabled both countries to satisfy domestic constituencies while providing an avenue for de-escalation, without the involvement of any external actor.

The 2019 Pulwama terrorist attack followed by the Balakot air strike introduced the element of unintended consequences. Elections in India were due in two months creating a more febrile political environment. Limiting response to non-kinetic retaliation was not an option. India mounted an air strike against a JeM terrorist training camp at Balakot. Aircraft crossed over into Pakistan for the first time since 1971. Further, Balakot was in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and not in the contested part of Kashmir under Pakistani control. Both actions were a step up from the 2017 surgical strikes. Indian media was quick to claim that Pakistan’s nuclear bluff had been called. The unexpected happened the following day when in an aerial dogfight between the two, an Indian plane was shot down. The pilot ejected and landed in Pakistani territory. Amidst rising rhetoric, external actors again stepped in. U.S. President Donald Trump claimed credit for defusing the situation, as did Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Pakistan claimed “air-superiority” and then took credit for “responsible behavior” by promptly announcing the return of the captured Indian pilot.

Notwithstanding shrill political rhetoric, the military authorities were cautious and measured in their statements during 2017 and 2019, taking care not to cross each other’s red lines. On both occasions, the Indian side emphasised that the limited objective of the retaliation had been met, the target was non-military, and the action was pre-emptive as there was reasonable intelligence about an imminent attack by terrorists gathering at the targeted location. The statements by the military authorities were carefully worded because notwithstanding the chest-thumping that is the staple of TV talk shows and the loose rhetoric employed by politicians, the military on both sides is conscious that military options available on both sides are limited, given current capabilities.

If Pakistan had developed a comfort zone that India would be deterred from kinetic retaliation in response to a cross-border terrorist strike, the Modi government’s actions were a signal that this would not be so. The age of paralyzing restraint was over and India would seek to expand the envelope for a level three conflict. Naturally, the Indian response would depend on the scale of terrorist attack and the visibility of ISI involvement, as well as Pakistan’s response in terms of either cooperating or engaging in denial. Significantly, the Modi government’s action has ensured that any future Indian government will now be pushed to undertake some form of kinetic action in response to a cross-border terrorist strike, however limited or modest.

An objective analysis would indicate that the Indian action is not enough to change Pakistani behavior and the “deterrence by punishment” under current capabilities is merely intended to assuage domestic audiences. India’s limited options help bring in the external actors with “off-ramp” de-escalation initiatives. In the past the United States has played the key role with others (notably China) playing a more supportive role. In 2019, for the first time, Saudi Arabia and the UAE indicated that they too had played a role. Traditionally, Saudi Arabia has been a significant partner for Pakistan, providing oil at concessional rates and financial support to address a balance of payments crisis, but the Modi government has been active in wooing the Gulf Arab countries. With the recent United States withdrawal from Afghanistan, how far the United States will remain engaged in India-Pakistan matters is open to question. Meanwhile, China can be expected to play a more prominent role given its growing investments in Pakistan’s infrastructure, but India is unlikely to find a Chinese role acceptable given the progressive downturn in India-China relations. Growing U.S.‒China differences may also make China less willing to countenance a leading U.S. role as it seeks to assert its influence in the region. In short, external actors may not be able to provide off-ramps in the future as readily as in the past.

Another takeaway is the different approaches that India and Pakistan adopt towards involvement of external actors and the “nuclear flashpoint” hypothesis that is a favorite for Western analysts and media. Pakistan uses this notion to highlight the centrality of the long-standing Kashmir dispute, hoping to catalyze some international involvement in the U.N. Security Council that would push for its resolution. International involvement is anathema to India; highlighting India’s commitment to bilateralism enshrined in the 1972 Shimla Agreement with Pakistan. Further, India responds to the “nuclear flashpoint” by highlighting Pakistan’s irresponsible behavior of nuclear saber-rattling (though Indian media and politicians have also been prone to this in recent years), A. Q. Khan’s well documented proliferation activities that earned Pakistan the sobriquet of a “nuclear Walmart,” and linkages of the Pakistani “deep state” with internationally proscribed terrorist outfits.

The Western analysts’ playbook was developed during the Cold War to deal with a stand-alone nuclear dyad, separated by an ocean, and through notions of arms control, non-proliferation, and crisis management. It is difficult to apply this playbook to asymmetric nuclear situations with the additional complexity of two neighboring states locked in a long-standing boundary dispute, one of whom is not averse to using proxy war, forcing the other to search for appropriate retaliation. The situation is rendered even more complex on account of Pakistan’s ever-closer strategic relationship with China, with whom India has had a difficult relationship since the 1962 border conflict and who is becoming increasingly adversarial and contentious.

5: The way forward

Virtually all India-Pakistan crisis escalation scenarios begin with a terrorist strike on Indian territory, followed by limited kinetic action by India using ground and/or airpower, Pakistani retaliation, and matters getting into an escalatory spiral. It is worth reflecting as to whether scenarios imply a tacit acceptance by the proponents of the “nuclear flashpoint,” which Pakistan’s army will continue to host and use such terrorist groups in a proxy war against India. Since this factor was absent in the United States‒Soviet Union deterrence dyad, it marks the first point of departure leaving India with the dilemma of discovering the scope and limits of kinetic action below the nuclear threshold, even as Pakistan seeks to diminish this space with its full spectrum deterrence policy.

Unless the international community can convince Pakistan to discard the policy of sub-conventional warfare using terrorists, which has long been part of its tool kit, the risk of inadvertent escalation will remain. The only countermeasure India can take is to strengthen its coastal and border surveillance and intelligence capabilities to thwart such efforts by restoring deterrence by denial and enhance its conventional kinetic capabilities, thereby strengthening punitive deterrence. The drawback is that this posture, which some refer to as “mowing the grass,” will be costly because it is unlikely to bring about a change in Pakistan’s policy.

Whereas India seeks to enhance its space for kinetic action without crossing Pakistan’s redlines, however, Pakistan seeks to blur these redlines to flash the nuclear card at the earliest possible time to draw in external actors. When India and China have periods of tensions on their border, for example, at Doklam in 2017 resulting in a stand-off that lasted 73 days, and in 2020 in eastern Ladakh, where the stand-off is ongoing (at the time of writing), the nuclear card has been absent in these periodic confrontations, even in the political rhetoric. There are two reasons for this difference that are worth examining. The first is that both countries, despite the asymmetry in their capabilities, have adopted a no-first-use policy as a key element of their nuclear doctrine. The second is that while India and China often allege incursions by the forces of the other side across the Line of Actual Control, there is no attempt by either side to pass this activity off as actions by non-state militants. These differences are instructive and explain why the nuclear factor does not cast a shadow on India-China boundary tensions even when these two parties engage in low-intensity military escalation. In contrast, Pakistan seeks to lower the nuclear threshold to hype the “nuclear flashpoint” to bring in external involvement to its advantage by constraining India. Undoubtedly the risks of India‒Pakistan nuclear escalation would certainly diminish if both sides had a no-first-use policy.

External involvement has often helped in defusing tensions between these two nuclear armed states. But it is an open question whether this will continue in the future given the changing geopolitical environment. In the past, China was willing to let the United States take the lead in the region in such matters. However, growing tensions between the two, coupled with the United States’ withdrawal from Afghanistan, may change the American and Chinese calculations, leaving the field open for Chinese diplomacy. Such a shift in great power roles is likely to be unacceptable to India, which is now increasingly voicing its threat perceptions in terms of a two-front war. Therefore, erstwhile external actors may not be able to play the same kind of role as in the past. This contextual shift means that some kind of dialogue between India and Pakistan has become essential for crisis management. India’s blanket rejection of any dialogue, maintaining that “terror and talks don’t go together,” implies a dependence on external actors for an off-ramp outcome and is not politically tenable in the long run.

In the United States‒Soviet Union nuclear standoff, the idea that deterrence was automatic was blown away during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 when the two came face to face in a full-blown showdown which brought the world closer to the brink of nuclear war that it had ever been. It also marked the beginning of a shared realization of the risks of unintended escalation that laid the foundations of bilateral and multilateral nuclear arms control. Therefore, while doctrinal asymmetry in the India-Pakistan case imposes its own constraints, the lesson that crisis management requires a minimal level of communication still holds. It is unlikely to resolve Kashmir or other fundamental differences; therefore, expectations need to be modest because any undue expectations will overload the process ensuring its collapse. If it proves its utility, then perhaps some confidence-building measures can be visualized, but acting on these will likely be further down the road.

At a regional level, a nuclear dialogue between India and China would help, particularly if Pakistan could also be drawn into a trilateral no-first-use understanding given that both India and China have adhered to it. The prospects for this breakthrough seem remote today because China has shied away from any nuclear talks with India as its policy remains intent on constraining India in South Asia. Growing tensions in the Sino-Indian relationship during 2020 have also deepened mistrust. Similarly, a global no-first-use agreement would put pressure on Pakistan to follow suit, but this approach is unlikely given the direction in which U.S. and Russian nuclear doctrines are evolving.

It is worth noting that while nuclear weapons remain the most destructive weapons designed to date, the science at its core is nevertheless 75 years old. In many ways, nuclear weapons are primitive weapons. A host of new disruptive technologies are emerging that add new complexity to the old deterrence equations. Foremost among these are missile defence capabilities, hypersonics—particularly as a dual-capable system—vastly improved surveillance and early warning systems that permit development of “left of launch” postures, and finally, offensive cyber activities that can hack into nuclear command and control networks. Pakistan is developing dual-use cruise missile systems and MIRV technologies; India is focusing on hypersonic weapons and missile defences. Any or all of these can give rise to new types of instability. If the development and deployment of these technologies are to be regulated and restrained, shared understanding on these new risks must be struck via dialogue. This process could be conducted at a bilateral level or even at a multilateral level. Similarly, many analysts have cautioned against interfering with nuclear command and control systems using offensive cyber capabilities; though as relations between major nuclear weapon states lock in a downward spiral, talks have not been possible. Yet, it is clear these technological developments will impact the deterrence equations rendering them even more fragile in the future than in the past.

III. ENDNOTES

[1] The two nation theory posits that Hindus and Muslims are two separate nations and therefore Muslims should have their own homeland distinct from a Hindu majority India. The Muslim League, led by Muhammed Ali Jinnah, used this to raise the demand for a separate homeland for Muslims.

[2] The census figures are drawn from the first census in both countries conducted in 1951, the 2017 census in Pakistan, and the census estimations for India just before the 2019 elections. A new census in India is due in 2021. A recent report in the New York Times also highlights the demographic trend in Pakistan (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/04/world/asia/pakistan-hindu-conversion.html?referringSource=articleShare)

[3] Many authors have written extensively about Pakistan’s search for an identity, but I have relied on the writings of the eminent Pakistani-American historian Dr Ayesha Jalal, recipient of Pakistan’s highest civilian awards Sitara – e- Imtiaz for her work. Dr Jalal’s works include The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League, and the Demand for Pakistan, New York: Cambridge University Press. (1985); The State of Martial Rule: The origins of Pakistan’s political economy of defence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1990); and The Struggle for Pakistan: A Muslim Homeland and Global Politics, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (2014).

[4] See “Keynote Address and Discussion Session with Lieutenant General (Retd) Khalid Kidwai,” February 6, 2020, at: https://www.iiss.org/events/2020/02/7th-iiss-and-ciss-south-asian-strategic-stability-workshop

[5] For the role of the Pakistani army in shaping the politics of Pakistan, I have relied on Hussain Haqqani, a former Pakistani journalist who also served as the Ambassador to Sri Lanka and the United States. He wrote, among others, Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military, published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2005) and Dr. C Christine Fair, a U.S. academic, Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War (Oxford University Press, 2014).

[6] SEATO was created in 1954 and included the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand, Philippines, Thailand, and Pakistan to prevent Communism from spreading in the region. It was disbanded in 1977 after the end of the Vietnam war.

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/seato

[7] Originally called the Baghdad Pact in 1955 and renamed CENTO in 1959, it included the United States, the United Kingdom, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, and Turkey and was disbanded after the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979.

https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/lw/98683.htm

[8] Feroz Hassan Khan, Eating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani Bomb, Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 2012.

[9] For a history of the Indian nuclear program, see George Perkovich, India’s Nuclear Bomb: The Impact on Global Proliferation, University of California Press (2002) and Ashley Tellis, India’s Emerging Nuclear Posture: Between Recessed Deterrent and Ready Arsenal, Rand(2001). For Pakistan, see Feroz Hassan Khan’s book in the previous footnote.

[10] The U.S. debate on deterrence has been captured by Bernard Brodie in his writings, the first being The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order. Harcourt, 1946 and Albert Wohlstetter P-1472: The Delicate Balance of Terror (The Rand Corporation 1958).

[11] “Evolution of India’s Nuclear Policy, Paper Laid on the Table of the House” (https://media.nti.org/pdfs/32_ea_india.pdf and Government of India, “The Cabinet Committee on Security Reviews perationalization of India’s Nuclear Doctrine,” Ministry of External Affairs Press Release, 4 January 2003 (https://mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/20131/The_Cabinet_Committee_on_Security_Reviews_perationalization_of_Indias_Nuclear_Doctrine+Report+of+National+Security+Advisory+Board+on+Indian+Nuclear+Doctrine)

[12] The first reference to these red lines is in a report of an Italian think tank Landau Network dated 14 January 2002. The report can be found here: https://pugwash.org/2002/01/14/report-on-nuclear-safety-nuclear-stability-and-nuclear-strategy-in-pakistan/. This is borne out by Brig (Retd) Feroz Hassan Khan in his paper Going Tactical (IFRI, September 2015) Footnote 58.

https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/pp53khan_0.pdf

[13] ISPR Press Release dated 19 April, 2011, https://www.ispr.gov.pk/press-release-detail.php?id=1721

[14] The history of Pakistan’s nuclear program has been documented by Brig (retd) Feroz Khan in Eating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani Bomb (Stanford University Press, 2012), while the Pakistani nuclear doctrine quotations also draw upon two lectures by Lt Gen (retd) Khalid Kidwai at the Carnegie Nuclear Policy Conference on 23 May 2015 (transcript – https://carnegieendowment.org/files/03-230315carnegieKIDWAI.pdf) and a subsequent one at the IISS on 6 February 2020 (https://www.iiss.org/events/2020/02/7th-iiss-and-ciss-south-asian-strategic-stability-workshop)

[15] Kristensen, Hans M., and Matt Korda, “World Nuclear Forces,” SIPRI Yearbook 2021, Oxford University Press, pp.333-412 https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/yb21_10_wnf_210613.pdf

[16] “Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor (PFBR),” Bharatiya Nabhikiya Vigyut Nigam Limited, https://bhavini.nic.in/userpages/viewproject.aspx

[17] Kristensen, Hans M., and Matt Korda, “World Nuclear Forces,” SIPRI Yearbook 2021, Oxford University Press, pp.333-412, https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/yb21_10_wnf_210613.pdf

[18] Kristensen, Hans M., and Robert S. Norris. “Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2015.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 71, no. 6 (November 2015): 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096340215611090

[19] Worldwide Threat Assessment by Daniel Coats on 13 February 2018

https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Testimonies/2018-ATA—Unclassified-SSCI.pdf

[20] Text of Donald Trump’s speech https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/full-texts-of-donald-trumps-speech-on-south-asia-policy/article19538424.ece

[21] Kuldip Nayar informs us: ‘Pakistan has nukes,’ Deccan Herald, 29 August 2018, https://www.deccanherald.com/specials/kuldip-nayar-informs-us-pakistan-has-nukes-689623.html

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.