DAVID VON HIPPEL AND PETER HAYES

JUNE 30, 2019

I. INTRODUCTION

In this Special Report, David von Hippel and Peter Hayes provide estimates of DPRK supply of and demand for petroleum products in recent years. Demand (and thus balancing supply) for key oil products in 2017 seems to have been considerably higher than official trade statistics would indicate, meaning that oil products are making their way into the DPRK economy in other ways.

David von Hippel is Nautilus Institute Senior Associate. Peter Hayes is Director of the Nautilus Institute and Honorary Professor at the Centre for International Security Studies at the University of Sydney.

Acknowledgments: The workshop was funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

This report is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here.

Banner image: DPRK oil refinery, Google Earth at 40°04’00.0″N 124°33’00.0″E here

II. NAPSNET SPECIAL REPORT BY DAVID VON HIPPEL AND PETER HAYES

ESTIMATES OF REFINED PRODUCT SUPPLY AND DEMAND IN THE DPRK, 2010 – 2017

JUNE 30, 2019

Overview

The supply of refined oil products in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) has been constrained to varying degrees since the breakup of the Soviet Union after 1990. The economic dislocation in the DPRK—due to severed access to concessional oil supplies, to markets for goods formerly made in the DPRK for use in Soviet republics and satellite nations, and to spare parts for factories largely provisioned by the USSR, among other factors—meant that crude oil and oil products imports in quantities consumed in 1990 and earlier became unaffordable for the DPRK. What imports were available after the early 1990s were at levels that constrained demand, meaning, for example, that vehicles were used less (and human and animal labor more) in transport and in farming, and that substitute fuels for various end uses became more important. In more recent years, the availability of oil products in the DPRK, at least from anecdotal evidence and based on statistics on imports of oil-consuming vehicles and equipment, appears to have been improved.[1] This trend has been interrupted to some extent starting in 2017 by United Nations Security Council (UNSC) sanctions targeting DPRK oil imports in response to the DPRK’s nuclear weapons and missile programs, but sanctions do not have appeared to have had the dramatic impact on the DPRK economy that the United States and others had hoped for, likely meaning that oil products are finding their way into the country by routes not reported in, for example, customs statistics.

This Special Report presents Nautilus’ estimates of refined oil product supply and demand in the DPRK for the years 2010 and 2014 through 2017, along with the methods and assumptions used to prepare these estimates, key conclusions, and a related comparison of a potential DPRK engagement strategy for humanitarian relief of some impacts of UN Security Council sanctions versus the volume of petroleum products use in the DPRK.

Key elements of these results presented in the sections that follow include:

- Estimated refined product balances, showing the origin of refined product supplies (that is, imported or produced in domestic refineries), use of refined product in energy transformation (such as electricity generation), and estimated demand for refined products by fuel and by sector.

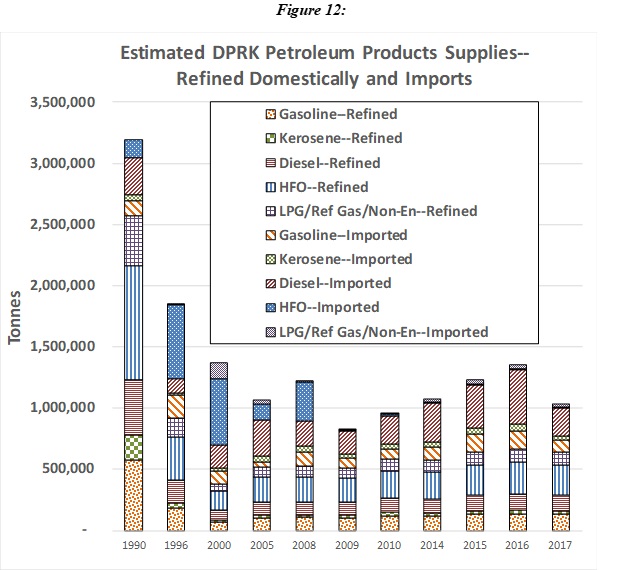

- Figures showing oil product imports and oil products refined in-country) by type of refined product for selected years between 2000 and 2017.

- Tables and graphs showing fuel demand by end-use sector (and for electricity generation) for diesel oil, gasoline (petrol) and kerosene/jet fuel.

- A brief description of the potential impacts of a program of rapid-deployment building energy efficiency and solar photovoltaic power measures, to be offered by the international community, that would address some of the humanitarian issues associated with UNSC sanctions on the DPRK related to coal exports and oil product imports without removing those sanctions.

Our analysis of DPRK oil products supply and demand shows fairly robust growth in the use of petroleum products in most sectors from 2010 through 2016. This growth included very rapid growth in the use of diesel fuel and gasoline to fuel imported internal combustion electricity generators imported in large quantities, particularly in 2014 through 2016. As UNSC sanctions game into full force, our analysis shows declines in oil products use in most sectors, as well as in electricity generation by households and organizations, between 2016 and 2017, due to the oil supply restrictions brought on by sanctions. Even with reduced demand, we found that a balancing was required between assumptions as to reductions in domestic demand for oil products from 2016 to 2017—given reports of only modest fuel shortages and evident reduction in economic activity in the DPRK as reported by visitors—together with what we assume, based in part on reports by others, must be the availability of additional “off-books” oil supplies procured by various means.

Although energy supply and, particularly, demand statistics are less complete than analysts might prefer in many countries, the DPRK is an outliner in terms of information provision, as it publishes essentially no direct information on its energy supply and demand. At the same time, its “energy insecurity”—that is, its lack of access to fuels, particularly petroleum fuels, and the energy services that those fuels provide, is, in our view, a key driver of its decision to pursue nuclear weapons and related missile technology development over the past three decades. As such, understanding the DPRK’s fuels supply and demand situation is critical to understanding potential solutions to the current political stalemate that international community actors might pursue.

Given the need to understand the DPRK energy sector, and the lack of direct data available, Nautilus Institute has built and updated its analysis of North Korean energy supply and demand by collecting as much available public sector data relating to energy use and the DPRK economy as possible, including anecdotal information from visitors, customs statistics from the DPRK’s trading partners, estimates on sectoral output by international and other organizations, and analyses of the DPRK economy by other researchers. This information was and is used to compile a “bottom-up” (demand-driven) analysis of changes to the DPRK economy, starting in 1990 (the last “normal” year for DPRK energy supply and demand), using with as much sector detail as can be included. In order to ensure that these estimates are internally consistent, we use an “energy balance” approach widely used to report national energy supply and demand worldwide, for example, by the International Energy Agency (IEA).[2]

Our DPRK energy analysis works includes the preparation of energy balances—in which supplies (imports, exports, domestic production) of fuels are balanced by their use and conversion to other forms in energy transformation processes such as oil refining and electricity generation, and ultimately by end-use demand—for all the fuels used in the DPRK economy.[3] In addition, we prepare estimated detailed supply-demand balances for oil products in particular, meaning for crude oil and for the refined petroleum products made from crude oil, whether domestically refined or imported. Our most recent estimated refined product balances for the DPRK are provided in the section of this report that follows.

Refined Products Balances, 2010 and 2014-2017

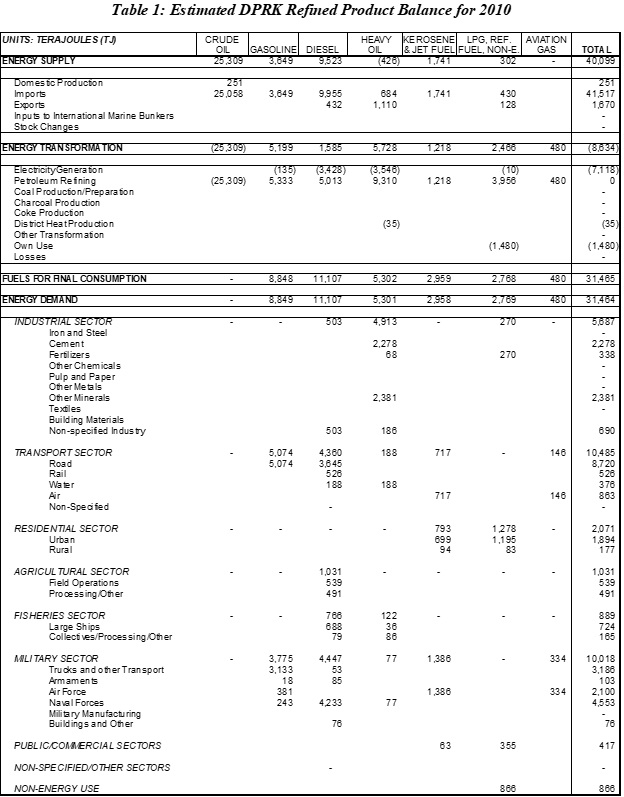

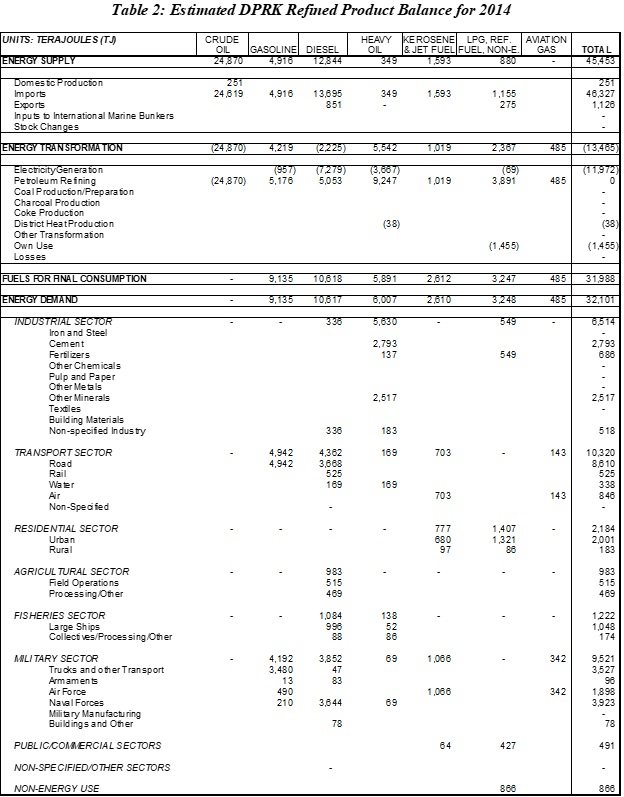

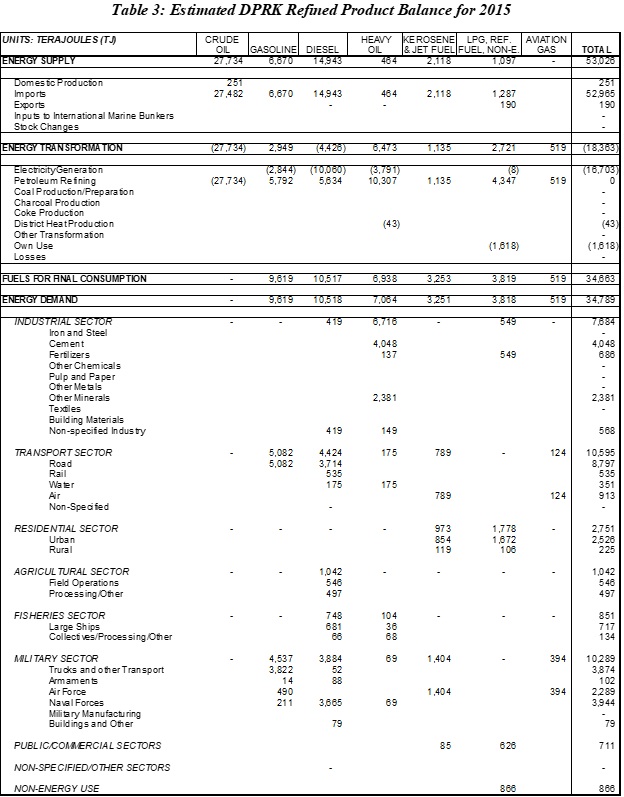

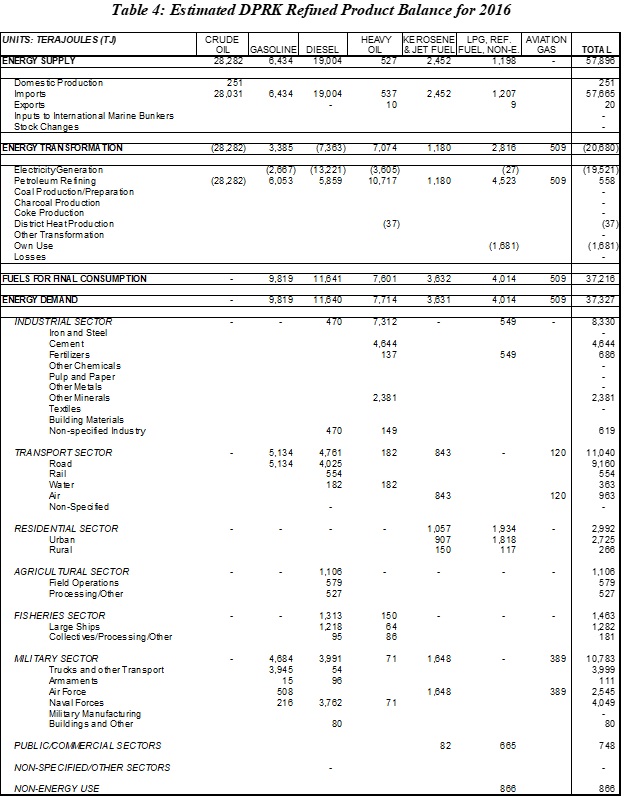

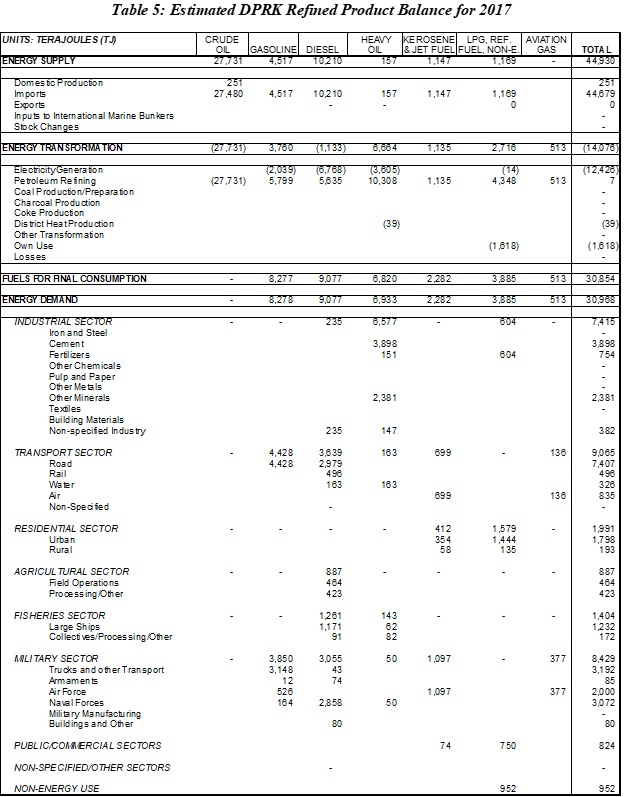

Table 1 through Table 5 present refined product balance tables for the years 2010 and 2014 through 2017, respectively. By our estimates, overall supplies of refined products increased by on the order of 25 percent between 2010 and 2016, with some of that increase being used to expand activity in the transport and other end-use sectors, but much of it going to fuel gasoline and, particularly, diesel-fueled generators, which had been imported in increasing number in previous years. Increased use of generators is an indicator of DPRK citizens and organizations taking more of the initiative in providing energy services—in this case electricity—in response to limited supplies of electricity from national and regional grids.

The supplies and thus use of oil products decreased between 2016 and 2017, by our estimates, as the impacts of UNSC sanctions on oil products imports, although it is our estimate that “off-books” imports of oil products must have continued at a significant level in 2017.

Refined Products Use by Sector and Fuel

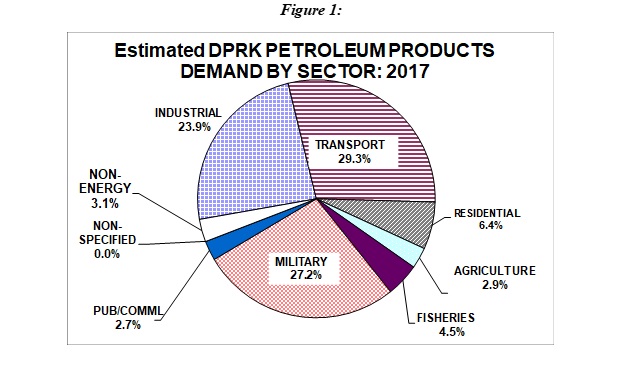

Overall estimated DPRK petroleum products demand by end-use sector (that is, not including electricity generation) is shown in Figure 1. The three major oil products end-use sectors in 2017 (other years 2010 through 2016 show similar patterns) were military, transport, and industry. Most industrial use was of heavy fuel oil, while the military and transport sectors used mostly diesel fuel and gasoline. Agriculture, fisheries (both mostly diesel), residential, and public/commercial (both using liquefied petroleum gas and kerosene) demand were each a small fraction of overall petroleum products use, as was non-energy petroleum use (consisting of feedstocks for industrial processes, asphalt, and other products).

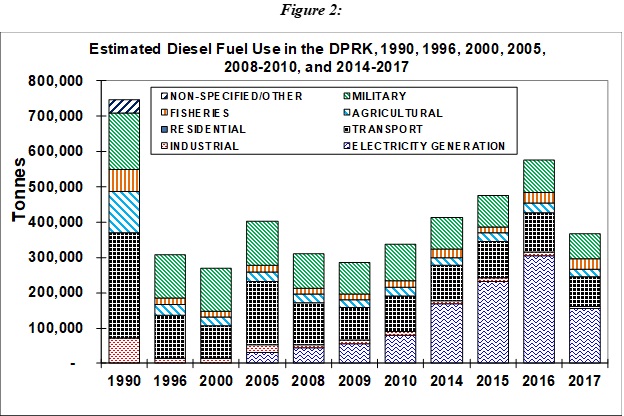

Use of most refined products (heavy fuel oil being the exception) increased from 2010 through 2016 due to enhanced availability and a more vibrant DPRK economy. Figure 2 shows estimated diesel fuel use over time. Diesel fuel use in the transport sector and agricultural sectors increased generally between 2010 and 2016, with increases in transport activity in diesel trucks offset somewhat by decreases in energy intensity (increases in energy efficiency), as newer trucks imported (largely) from China were incorporated into the DPRK fleet. Diesel use in the military changed relatively little, based on our estimates, as there was not a marked change in military activity during the 2010-2016 period, or at least little change that would affect fuel use. The largest change in diesel use during 2010 through 2016 was in the use of diesel for electricity generation, as the combination of broader availability of diesel, increased imports of generators, and continued unreliable electricity supplies allowed consumers to generate more of their own power. We estimate this trend to have changed markedly in 2017, when reduced fuel availability caused reductions of diesel use in virtually all sectors, but particularly for electricity generation.

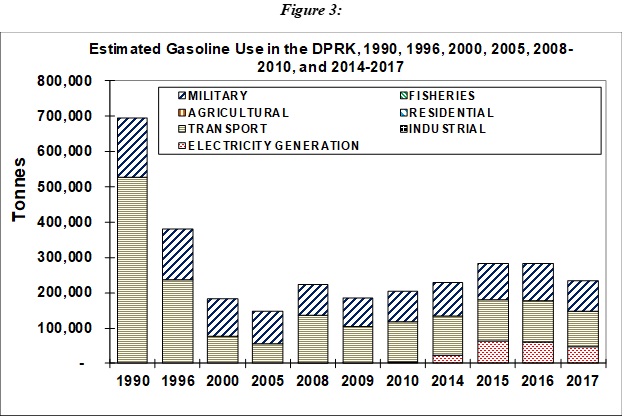

Figure 3 shows estimated trends in gasoline use by year. Here the marked increase from 2010 through 2015 stalls in 2016 as estimated supplies did not continue to expand in that year, and declines in 2017 due to reductions in gasoline availability due to USNC sanctions. These reductions were estimated to be not quite balanced by increases in off-books imports. To some extent, and mostly in rural areas, reduced gasoline (and diesel) availability may have been compensated for by a rise in the use trucks adapted to use “gasifiers” fueled with wood, crop waste, charcoal, and/or coal as a substitute for gasoline. Use of such trucks has been reported regularly during the last three decades in the DPRK, but may have risen in the last few years.[4] As with diesel fuel, the years since 2010 have seen a marked rise in the use of small imported personal/household generators (perhaps 500 to 2000 watts) fueled with gasoline, although we estimate the use of such generators declined in 2017 when fuel availability fell and DPRK market prices, at least in some areas, rose.[5]

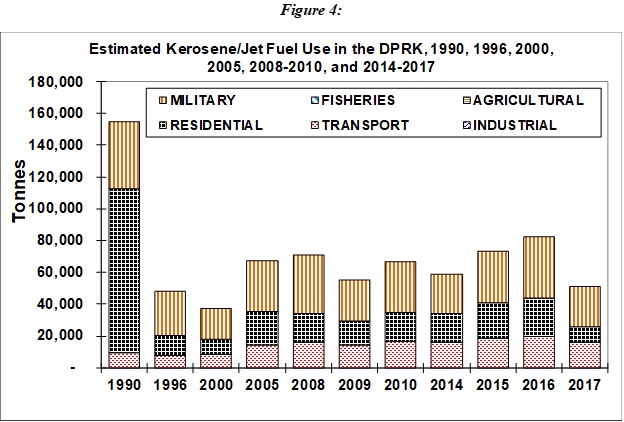

Figure 4 shows estimated kerosene and jet fuel use in the DPRK over the years, divided mostly between use in the transport sector (for jet transport), the military (for military aircraft) and in the residential sector (as a lighting and cooking fuel). We assume that all of these end-uses declined significantly between 2016 and 2017. Unlike diesel and gasoline, we have heard little suggesting that off-books trade in kerosene and jet fuel has been significant in recent years, though such trades are of course possible. The reduction in transportation use of jet fuel between 2016 and 2017 probably meant fewer domestic flights on jet-engine aircraft, as we assume that international flights (most relatively short, by the national carrier Air Koryo) probably fueled up in their destination countries. The decline in kerosene use in the residential sector could have been partially compensated for by the use of other cooking fuels (biomass and coal, foe example), and/or the use of alternative lighting fuels, such as electricity from photovoltaic panels. The reduction in military jet fuel use between 2016 and 2017 probably stemmed from a reduction in training flights in fighter and other jets; such flights were already at what would be considered a low level for most other militaries.

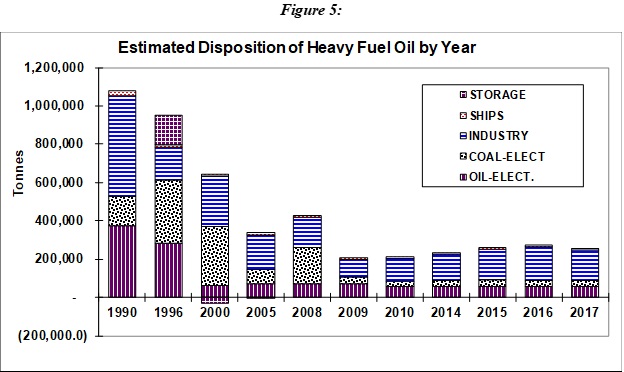

Heavy fuel oil (also sometimes called residual fuel oil) has limited uses in the DPRK. It is used in a very few freighters and ships of the DPRK navy, for some industrial processes (as a fuel, albeit not a major fuel, for cement making and for minerals processing), and as a fuel for electricity generation in two or three power plants designed to use oil, plus as a starter fuel (typically only a percent or two of total fuel use) for coal-fired power stations and district heating boilers. The trend in disposition (use/storage) of heavy fuel oil by year is shown in Figure 5. We estimate that heavy fuel oil use rose somewhat between 2010 and 2016, with most of the increase being in the industrial sector, and declined only slightly between 2016 and 2017.

DPRK Domestic Oil Products Production

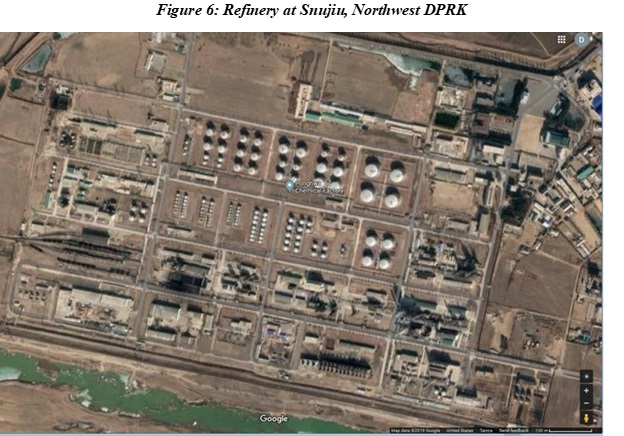

The DPRK has two major larger oil refineries, located near the border with China at Sinuiju and near the border with Russia at Sonbong. The refinery at Sinuiju, the Pongwha Chemical Factory (see Figure 6) is supplied via a crude oil pipeline from China and appears to have operated more or less continuously for three or more decades. A refinery of somewhat larger capacity, the Seungri Chemical Complex refinery, in the DPRK’s northeast near Sonbong, was fueled with Russian, and then Middle Eastern, crude oil in the 1980s and early 1990s, but has reportedly operated only sporadically since, and perhaps hardly at all in the last decade (see Figure 7). A third refinery, of relatively small capacity and using fairly basic technology, was reportedly in use in the Nampo area, possibly operated by the DPRK military.

Source for Figure 6:[6]

Source for Figure 7:[7]

There have been reports of crude oil production in the DPRK dating to the 1990s and possibly earlier, including an onshore well and possibly some offshore production. These reports have been difficult to corroborate, and though experts contacted by the authors believe there is probably (or at least has been) some domestic DPRK oil production, the quantity produced appears to be (or have been) small. We assume production of just under 6 thousand tonnes annually, about 1 percent of what the DPRK imports from China, but that must be seen as a rough estimate.

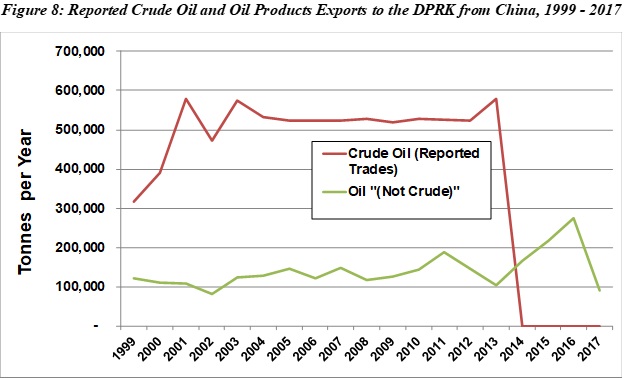

Although crude oil imports to its refinery in Sonbong have dwindled over the years, the DPRK continues to import oil by pipeline to its Sinuiju refinery. These crude oil flows were reported in China’s customs statistics through 2013, when reporting stopped, although the flows of oil apparently have not. A recent article confirmed that China continues to send crude oil across the border to the DPRK, in part because the waxy nature of the oil means that if flows are allowed to stop, particularly during cold weather, it would be very difficult to return the pipeline to operation. We have assumed that 2014 crude oil exports from China to the DPRK via pipeline were 578,000 tonnes, the same as was reported in customs statistics in 2013, and were 645,000 tonnes from 2015 through 2017.[8] Figure 8 summarizes crude oil and refined oil product exports to the DPRK from China since 1999, as reported in Chinese customs statistics.

Figure 8: Reported Crude Oil and Oil Products Exports to the DPRK from China, 199 – 2017[9]

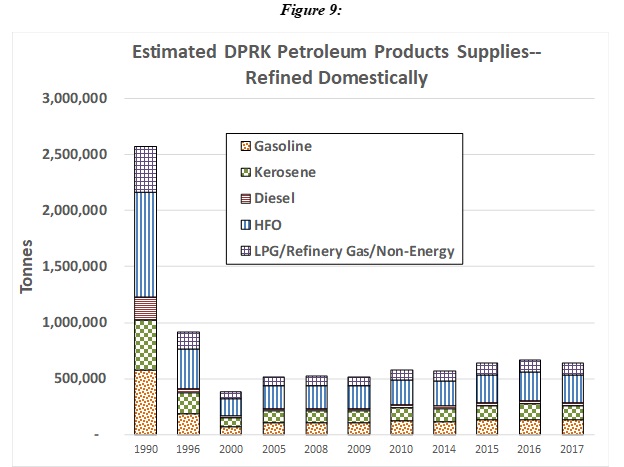

Figure 9 presents our estimates of refined products outputs by the DPRK’s refineries through the years. Most evident here is the drop-off in output between 1990 and 1996 and later years. As 1990 was arguably the last “normal” year for the DPRK economy—the impacts on the DPRK of the collapse of the Soviet Union were just starting to be felt then—the difference between 1990 and subsequent refined products output is an indicator of the DPRK’s “energy insecurity”, that is, the restrictions in the availability of fuel that has been in significant part driving DPRK policies. By our estimates, refined product output, constrained largely by the availability of crude oil imports, mostly from China, has changed relatively little since 2010.

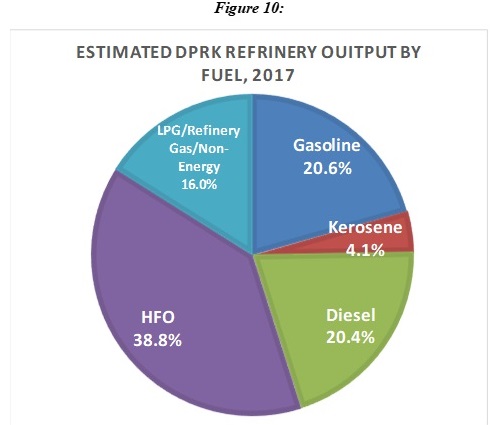

Our estimates of the fractional outputs of refined products by fuel type in the DPRK in 2017 are presented in Figure 10. In general, the ability of a given refinery to change the fractions of the different products it produces is limited by the refinery’s infrastructure and by the type of crude oil it uses. As a consequence, for example, although the DPRK’s needs for gasoline and diesel are greater than its needs for heavy fuel oil (HFO), it is constrained by the type of reactors available at its refinery and the composition of the crude oil that it (mostly) gets from China to produce more HFO then either of the more valuable motor fuels. Technological upgrades to the DPRK’s refineries—addition of catalytic cracking equipment, for example—could allow them to produce more of the products needed by the economy, as could use of different types of crude oil, if and when such imports (or, likely further into the future, oil from domestic resources) are available.

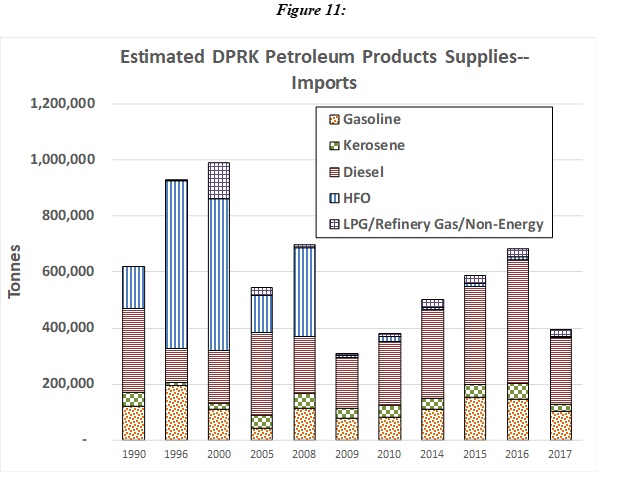

DPRK petroleum products imports, by our estimates, increased sharply between 2010 and 2016, providing fuel for the economic growth in the DPRK witnessed by many visitors (see Figure 11). We estimate that refined product imports declined in 2017 due to the enforcement of UNSC sanctions by the international community, also a significant volume of refined products still must have reached the DPRK through “off-books” channels.

Oil products imports have reached and reach the DPRK in a variety of ways:

- Official (that is, reported through customs statistics) oil product exports from China. Up until about 2010-2015, this was the largest source of oil products imports to the DPRK in most years, and included many different categories of fuels and non-fuel oil products. In recent years, official oil product trade from China to the DPRK have fallen dramatically, as a result of USNC sanctions. We assume that this oil has entered the DPRK mostly by sea-borne tanker, but some doubtless also arrives across the DPRK’s northern border in rail tanker cars and trucks.

- Official (on-books) trade of oil products—largely, it appears, diesel fuel—from Russia to the DPRK. This reported trade has tended to vary significantly from year to year, with some years showing trades of hundreds of thousands of tonnes (2005 to 2007, for example), and others showing trades of only a few thousand tonnes (2009, 2012, 2016, and 2017, for example). These shipments are also by ship, rail, and truck.

- Official (reported in customs statistics) shipments from other countries to the DPRK, including spot market purchases from oil trading centers such as Singapore. In most recent years, these imports have been in the thousands to tens of thousands of tonnes, from a variety of countries around the world. In some cases, however, we have assumed that trades must have been reported in error. For example, we find it unlikely that India sold 800,000 tonnes of gasoline to the DPRK in 2008 for three-quarters of a billion dollars. It seems more likely that this trade was mis-reported, and actually involved the Republic of Korea (that is, was mistakenly recorded as exports to North Korea rather than South Korea) or another country.

- Unofficial (not reported in customs statistics) trades involving Chinese companies, including, for example at-sea ship to ship transfers of oil.[10]

- Unofficial or semi-official (not reported in customs statistics, but in some case acknowledged by Russian authorities) shipments of oil from Russia to the DPRK.[11] [12]

- Smuggling of oil from unknown sources.[13]

The first three of these import modalities are (to the extent that customs statistics are accurate) are straightforward to quantify. The last three are quite difficult to quantify, and probably, absent the most advanced and assiduously applied intelligence tools (which are certainly not available to the authors of this paper), impossible to quantify accurately.

In order to estimate “off-books” imports of oil products to the DPRK in recent year, we have adopted and adapted estimates from several sources (including those above), then estimated what a reasonable reduction in DPRK oil products use might be to meet the level of estimated supply, taking into account the apparently modest economic impacts of oil supply reductions on the DPRK economy that has been observed by visitors in recent years.

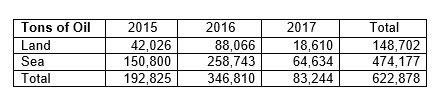

In the report The Rise of Phantom Traders: Russian Oil Exports to North Korea, dated July 2018, The Asan Institute for Policy Studies estimates, based on tracking customs transactions between the Russian firm Independent Petroleum Company (IPC) and three North Korean business entities, that refined oil product sales to the DPRK in the years 2015 through 2017 were as follows:[14]

These figures are reasonably consistent with the estimates offered in both the references cited above (Reuters article quoting President Putin, and quote from DPRK émigré) We therefore assume that the Asan Institute estimates apply as the total amount of oil exported “off books” from Russia to the DPRK in 2015 through 2017, and further estimate that 90 percent of the oil products in these shipments were diesel fuel, with the other 10 percent being gasoline, based roughly on the pattern of on-books trades in the two products from 2005 through 2017 (based on customs statistics). We further assume that this pattern of trade was established prior to 2014, but that in 2014 imports from Russia by this mode were a bit lower, at 180,000 total tonnes, with diesel and gasoline (or similar products) sold in approximately the same proportions as assumed for 2015 through 2017.

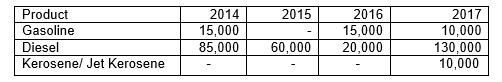

Comparing the total supplies based on the off-books estimates above with trends in demand, we assume that there were at least some oil product imports to the DPRK that are not captured in any of the statistics or estimates of “off-books” trade above. These imports may come from Russia, China, or other international vendors, and may be coming in by land or sea. They may be barter trades or products imported via the black market. Our assumptions as to imports by product, from 2014 on, are as follows (tonnes):

For 2017, when UN Security Council restrictions on oil imports were in full force, our assumption is that without a significant amount of fuel–likely diesel, beyond imports described in customs statistics and off-books imports from Russia above, signs of fuel shortages, particularly for diesel fuel would have been more evident in the DPRK than visitors describe. We therefore assume that there were reductions in fuel use across the board, but also the amounts of fuels shown above made their way into the country. For example, the 130,000 additional tonnes of diesel fuel we assume were imported “off-books” is more or less consistent with the (sanctions-evading) shipments recorded as received or planned through a Taiwanese company, as reported by the UNSC “Panel of Experts”.[15]

Considerations in Analysis of Recent DPRK Oil Product Supply and Demand

Key caveats to the analysis presented above include:

- Although we have done our best to estimate energy demand by sector, based on what is known about physical sectoral outputs, and what can be guessed at based on reports by visitors and other analysts, there is little solid information about energy demand in the DPRK. As such, although we provide trends that seem consistent with availble information, true figures, if indeed they are ever ascertained, may be different.

- For the years 2014 through 2017 we have estimated volumes of oil products imported “off-books”, that is, not captured in customs statistics, that exceed the volumes of such imports estimated by others, because we feel that it A) likely that some off-books imports have inevitably gone undetected, and B) assuming that our energy demand results for earlier years are reasonable, it seems improbable that DPRK oil products demand could decrease enough to account for the decrease in reported (on- and off-books) fuels imports without severe and visible economic dislocation, which visitors have not reported.

- It is possible that off-books imports were either greater than we have estimated, in which case served demand for oil products would be higher (particularly in 2017) than we show in the tables and figures above, and.or that some of the oil product demand in 2017 was served by drawing down stocks of oil products. If we had to guess, we would probably say that off-books imports were greater than we have estimated, rather than less.

Potential Energy Impact of Humanitarian Engagement Strategies Relative to DPRK Oil Imports

In a Nautilus Institute Special Report published in 2018, David von Hippel and Peter Hayes described a rapid-deployment (6 months) $100 million “Program” of humanitarian energy assistance and engagement that the international community might provide for the DPRK (see https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/rapid-relief-of-humanitarian-stress-from-energy-sanctions-building-energy-efficiency-and-solar-pv-measures-for-rapid-installation-in-pyongyang/). The Program centers on the use of A) building energy efficiency measures in apartments in the DPRK, likely in Pyongyang, to provide heating services to residents, and B) installation of solar photovoltaic mini-grids in schools and clinics to provide to reliable power for those facilities. Both sets of measures provide opportunities for on-the-ground and highly visible engagement between the international community and the DPRK.

The 50,000-apartment building energy retrofit (insulation, improved windows and doors, weatherstripping, heating controls, and other measures) we propose would reduce coal use (assumed to be central heating) by about 900 TJ (terajoules, a unit of energy equivalent to about 24 tonnes of oil products) annually, or 22,000 TJ over the lifetime of the measures. An alternative to providing heat with coal-fired central heating (or boilers) in the DPRK might be to use diesel-fueled generators (which have been imported in large numbers in recent years, see https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/dprk-imports-of-generators-in-recent-years-an-indication-of-growing-consumer-choice-and-influence-on-energy-supply-decisions/) to produce electricity, then for apartments to use electrical resistance heat. If heating is provided via diesel generating sets, the savings in fuel from the building energy efficiency measures is about 2400 TJ/yr, or about 60,000 TJ over the lifetime of the measures.

The photovoltaic (PV) installations (about 14 MW total) for schools and/or clinic would save 300 TJ per year in displaced coal for electricity generation or about 7,000 PJ over the life of the systems.

By way of comparison with refined products volumes, the 1200 (900 + 300) TJ of displaced coal per year would be about 4% of the approximately 31,000 TJ of diesel, gasoline, kerosene/jet fuel, and LPG that we estimate was used in the DPRK (including for electricity generation) in 2017. The 31,000 TJ excludes heavy fuel oil, but includes all sources of refined products, both licit and “off-books”. Using the “genset-and-resistance-heating” comparison, the total rises to 2700 TJ/yr, or about 9 percent of refined products use (again excluding heavy oil). The analog to the 31,000 TJ figure for 2017 in 2016 is about 44,000 TJ , meaning that our estimate is that demand for these fuels (including for electricity generation) fell by about 13 PJ between 2016 and 2017 as a result of accommodations to lower availability of oil product supplies in the DPRK (including reduced fuel use and, in some sectors, fuel substitution) due to UNSC sanctions.

If our six-month program is ramped up to approximately four times its size in a 2-year engagement strategy, the expanded program would save coal use on the order of 16 percent of DPRK 2017 petroleum products supplies, which would be about half (in TJ) of what we estimating the DPRK reduction in oil use between 2016 and 2017 might have been. If one assumes that some or all of the program is displacing electricity generation by diesels to generate heat for apartments, the relative savings is greater.

This type of engagement serves to relieve some of the humanitarian impacts of sanctions, with a particular focus on addressing impacts on ordinary DPRK citizens, but leaves the sanctions regime largely intact pending progress in denuclearization talks. It thus represents an important option for engagement and confidence-building while talks continue, with few “downsides” in terms of potential diversion of significant benefits to the DPRK military or elites.

We estimate the overall supplies of oil products in the DPRK as shown in Figure 12. Refined products produced (almost entirely) from crude oil imported by pipeline from China serve as a consistent, if minimal, supply for the DPRK economy, but it has been imports, which increased markedly from 2010 to 2015, that have allowed the DPRK economy to grow. Some of these imports were from on-books (customs-reported) trades, but many most likely were not, particularly after the advent of UNSC sanctions. We estimate that 2017 oil supply (and thus use) was less than in 2016, based on at least transient price spikes for diesel and gasoline as reported by visitors to the DPRK, but do not see the type of reductions in oil product araciality that the authors of the UNSC sanctions on oil product imports probably hoped to see. It is possible that 2017 oil supplies to the DPRK were in fact greater than we have estimated, but we don’t think it is likely that supplies would have been much less.

As time goes on, it is likely that the DPRK will get more adept, rather than less, in obtaining off-books the oil imports that it needs. We therefore suggest that an even stronger emphasis on engagement with the DPRK by the international community is called for on issues vital to its energy security (and addressing its energy insecurity), such as the building energy efficiency/renewable energy engagement strategy described above.

III. ENDNOTES

[1] See David von Hippel and Peter Hayes (2018), DPRK Motor Vehicle Imports from China, 2000-2017: Implications For DPRK Energy Economy, NAPSNet Special Reports, August 23, 2018, available as https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/dprk-motor-vehicle-imports-from-china-2000-2017-implications-for-dprk-energy-economy/, and David von Hippel and Peter Hayes, DPRK Imports of Generators in Recent Years: An Indication of Growing Consumer Choice and Influence on Energy Supply Decisions?, NAPSNet Special Reports, November 02, 2018, available as https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/dprk-imports-of-generators-in-recent-years-an-indication-of-growing-consumer-choice-and-influence-on-energy-supply-decisions/.

[2] See, for example, the IEA compendium available for sale at http://data.iea.org/payment/products/117-world-energy-balances-2019-edition-.aspx, or the energy balances published by the Korea Energy Economics Institute for the Republic of Korea (ROK) as a part of (for example) Energy Info Korea 2017, available as http://www.keei.re.kr/keei/download/EnergyInfo2017.pdf.

[3] Previous versions of our DPRK energy analysis work for all fuels are David von Hippel and Peter Hayes (2012), Foundations of Energy Security for the DPRK: 1990 – 2009 Energy Balances, Engagement Options, and Future Paths for Energy and Economic Development, dated September 13, 2012, and available as

https://nautilus.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/1990-2009-DPRK-ENERGY-BALANCES-ENGAGEMENT-OPTIONS-UPDATED-2012_changes_accepted_dvh_typos_fixed.pdf; and David von Hippel and Peter Hayes (2014), An Updated Summary of Energy Supply and Demand in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), NAPSNet Special Reports, April 15, 2014, available as https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/an-updated-summary-of-energy-supply-and-demand-in-the-democratic-peoples-republic-of-korea-dprk/

[4] A Radio Free Asia article entitled “Charcoal-powered Vehicles Stage a Comeback in North Korea”, dated 2016-12-09, reported by Jieun Kim, translated by Soo Min Jo, written in English by Roseanne Gerin, and available as https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/charcoal-powered-vehicles-make-a-comeback-in-north-korea-12092016160533.html, describes the resurgent use of “charcoal” fueled trucks in particularly rural parts of the DPRK, and in the Northeast city of Chongjin, for transport services of all kinds, including transport for hire. The article notes the use of these gasifier trucks (which we assume are actually using charcoal, wood, crop waste, coal, and/or waste oil fuels, as available locally, in on-truck gasifiers), has increased in recent years in some locales due to fuel restrictions, possibly due to sanctions. 1, 2.5, and 15, and 20-tonne truck models have been seen using the technology, but it appears that the 2.5-tonne, DPRK-made Seung-ri 58 (Victory 58) model is most frequently seen fueled by gasifiers. The article also notes that around 70 percent of gasifier-driven trucks (presumably in the specific area described) are from rural military units.

[5] For example, a July 24, 2018 Reuters article entitled “Exclusive: North Korean fuel prices drop, suggesting U.N. sanctions being undermined”, by Hyonhee Shin, and available as https://www.reuters.com/article/us-northkorea-economy-exclusive/north-korean-fuel-prices-drop-suggesting-u-n-sanctions-being-undermined-idUSKBN1KE15F,

includes the following passage: “China said on Tuesday it strictly abided by U.N. sanctions, but indicated it may have resumed some fuel shipments to North Korea in the second quarter of this year. Gasoline was sold by private dealers in the North Korean capital Pyongyang at about $1.24 per kg as of Tuesday, down 33 percent from $1.86 per kg on June 5 and 44 percent from this year’s peak of $2.22 per kg on March 27, according to Reuters analysis of data compiled by the Daily NK website. Diesel prices are at $0.85 per kg, down about 17 percent from March. The website [that collects price data] is run by North Korean defectors who collect prices via phone calls with multiple traders in the North after cross-checks to corroborate their information, offering a rare glimpse into the livelihoods of ordinary North Koreans.”

[6] From Google Maps, accessed May 23, 2019, https://www.google.com/maps/place/Sinuiju,+North+Pyongan,+North+Korea/@40.0735202,124.5453298,964m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x5e2afe38ccd630eb:0xd9765aa741246bf5!8m2!3d40.0823213!4d124.4489192.

[7] From Google Maps, accessed May 23, 2019, https://www.google.com/maps/search/sonbong+refinery/@42.3113238,130.348157,2387m/data=!3m1!1e3.

[8] A 2018 article in NK Economy Watch, “Chinese oil exports to N Korea increased after KJU’s third visit to China”, dated July 19th, 2018, by Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein includes the following passage: “China also dramatically increased oil shipments to the North. A source in Beijing said it nearly doubled crude oil supplies to the North through pipelines from Dandong since Kim’s recent visits. ‘Some 30,000 to 40,000 tons of oil is enough in the summer to maintain the lowest possible flow of oil in the pipelines to ensure that they don’t clog, and about 80,000 tons in winter,” the source added. “Though it’s summer now China has recently increased flow to the winter level.” Original source, “China Doubles Oil Shipments to N.Korea After Kim’s Visit”, Lee Kil-seong and Kim Myong-song, Chosun Ilbo, 2018-07-19. Assuming that this physical reason for China to maintain minimum flows through the pipeline is correct (and we have heard this explanation elsewhere), one can estimate a minimum flow through the pipeline in a “normal” year by assuming 35,000 tonnes per month over a 7-month (April-October) “summer” season of warmer months, with a corresponding average of 80,000 tonnes per month over the remainder of the year, which would yield an average of 645,000 tonnes of crude oil annually. We assume crude imports via pipeline at this rate from 2015 through 2017, with 2018 imports likely, based on the above, to be at least somewhat higher.

[9] Data from United Nations Comtrade Statistics, https://comtrade.un.org/.

[10] See, for example, Yosuke Onuchi (2019), “North Korea’s oil smuggling blows past import cap: UN report:

Ship-to-ship transfers become increasingly sophisticated”, Nikkei Asian Review, dated February 26, 2019, and available as https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Trump-Kim-Summit/North-Korea-s-oil-smuggling-blows-past-import-cap-UN-report.

[11] For example, a Reuters article in 2017 (“Russia says its oil supplies to North Korea are negligible”, by Denis Pinchuk, dated September 5, 2017, and available as https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-northkorea/russia-says-its-oil-supplies-to-north-korea-are-negligible-idUSKCN1BG13N), quotes Russian President Vladimir Putin as saying “We have supplies of 40,000 tonnes of oil and oil products to North Korea a quarter”, which would imply about 160,000 tonnes per year. This is close to the lower end of the range of oil exports from Russia to the DPRK, as estimated by other analysts.

[12] A North Korean émigré has been quoted in various publications as estimating that Russia exported 200,000 to 300,000 tonnes of oil products annually in recent years to the DPRK via dealers based in Singapore (“,,,Ri Jong Ho, a former official in North Korea’s Office 39, supplied in a recent interview with Kyodo News..”). See, for example, Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein (2017), “North Korea’s ICBM-test, Byungjin and the economic logic”, dated, July 4th, 2017, and available as http://www.nkeconwatch.com/category/energy/oil/.

[13] Courtney Kube and Dan De Luce (2018), “Top secret report: North Korea keeps busting sanctions, evading U.S.-led sea patrols”, NBC News, dated December 14, 2018, and available as https://www.nbcnews.com/news/north-korea/top-secret-report-north-korea-keeps-busting-sanctions-evading-u-n947926.

[14] Asan Institute report available as document available as http://en.asaninst.org/wp-content/themes/twentythirteen/action/dl.php?id=45032; data shown from table on page 27 of that report.

[15] From paragraphs 71 and 72 of UNSC (2018), Note by the President of the Security Council, number S/2018/171, Annex: Letter dated 1 March 2018 from the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009) addressed to the President of the Security Council, available as http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2018/171&referer=/english/&Lang=E.

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent