By Sun-Jin Yun, Myungrae Cho and David von Hippel

September 13, 2011

Nautilus invites your contributions to this forum, including any responses to this report.

——————–

CONTENTS

IV. Nautilus invites your responses

Protesters hold a candle-light vigil against the ‘Four Major Rivers Restoration Project’, part of South Korea’s ‘Green New Deal’. (photo: Asianews.it)

I. Introduction

Sun-Jin Yun, Professor at the Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Seoul National University and Myungrae Cho, Professor, Dankook University, write “The ROK’s green growth strategy, as currently formulated, includes some impressive targets and demonstration projects, but at its heart emphasizes economic growth and national industrial competitiveness rather than being a true plan for “greening” of the Korean economy. As such, the ROK’s current “green” policies are in effect mostly policies for further benefiting existing large ROK industries, including the nuclear and construction industries.”

The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Report

– “The Current Status of Green Growth in Korea: Energy and Urban Security”

By Sun-Jin Yun, Myungrae Cho and David von Hippel

The Republic of Korea’s economy has been one of the economic marvels of the last few decades, growing rapidly and steadily, with few downturns. By 2010, the ROK had the world’s 12th largest GDP, and ranked 10th among nations in electricity consumption and production, 10th in gas imports, ninth in oil consumption, and fourth in oil imports. [1] The ROK has become an international force in several industries, including steel, automobiles, and electronics, and has seen a vast increase in the living standards of its people, as well as in urbanization. Like Japan, much of the ROK’s energy needs are supplied by imports, and like Japan, the ROK has embraced nuclear power as a key source of electricity. Unlike Japan, however, for the ROK the DPRK serves as a much more significant factor, albeit a quite uncertain one, in the development of energy systems and the drive toward energy security in the DPRK.

The last decade has seen some transitions in the ROK energy sector, including a move toward partial restructuring of its electricity sector, expanded investment in oil and gas producer nations, and a drive toward exports of nuclear technologies. The last few years, as of 2011, have also seen the development, and the very early phases of implementation, of green economy principles in South Korea, and of policies related to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. In the sections that follow we provide some background on the energy sector and energy security policies in the ROK, describe the genesis and current status of green economy and GHG emissions reduction policies and projections, review the strengths and weakness of existing green economy policies, and suggest how green economy and energy security policies in the ROK might interact with issues such as urban security, climate change, and improvement of the DPRK situation. [2]1.Overview of the ROK’s energy and economic situation

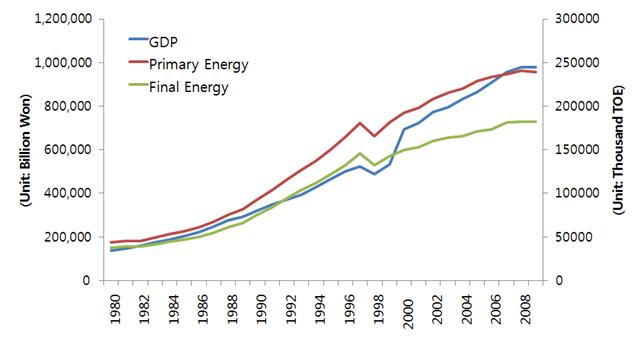

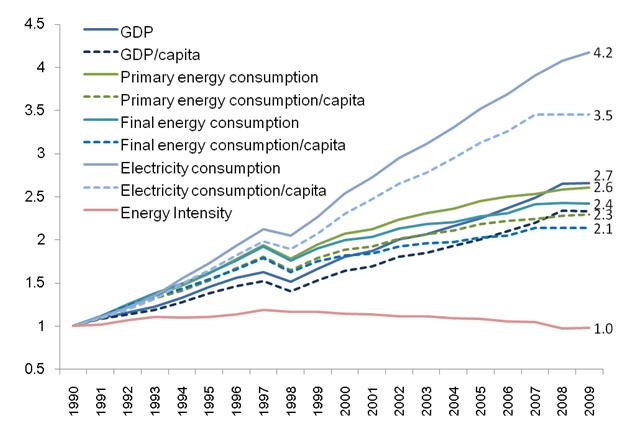

As of the end of the Korean War, the ROK’s economy and infrastructure, to the extent that it had survived the ravages of the conflict, was largely agricultural, with most energy provided by biomass (wood and crop wastes) and from the ROK’s modest reserves of anthracite coal. The country’s rapid industrialization, particularly in the last 30 years, has been fueled largely with imported energy, such that as of now only a few percent of energy is supplied from domestic sources, and much of that is combustion of municipal and other wastes. By 2010, domestic coal constituted only about 1.8 percent of total ROK coal use, and much less than one per cent of total energy use. [3] Figure 1 shows the trends in ROK GDP, primary energy use (that is, including inputs to processes such as electricity generation and oil refining), and final energy use (use of energy by consumers). Both GDP and primary energy use have increased approximately 5-fold since 1980, with strong growth throughout the period with the exception of during the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 to 1998. As implied in Figure 1 and shown more clearly in Figure 2, the trend in intensity of energy use, that is, the use of energy per unit of ROK GDP, has shown two distinct trends, increasing (more energy use per unit GDP) until about 1997, then slowly decreasing, through 2007, due to a combination of greater efficiency of energy use and a slow shift to less energy-intensive industries. Although the growth in energy consumption exceeded the growth in GDP in every year from 1988 through 1997, since 1999, growth in GDP has exceeded growth in energy consumption in every year except 2003. Electricity consumption has grown faster than primary or final energy consumption as ROK consumers, as end-uses of electricity have increased faster than those for other fuels.

Figure 1: GDP, Primary Energy Use, and Final Energy Use in the ROK, 1980 – 2009 [4]

Figure 2: Trends in Economic and Energy Sector Activity in the ROK, 1990 – 2009 [5]

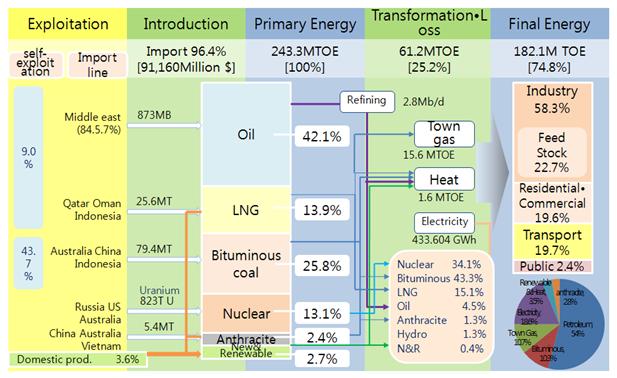

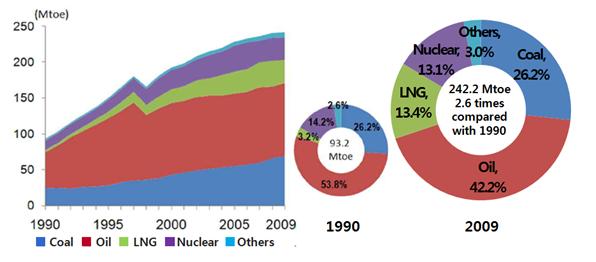

Figure 3 provides a schematic summary of energy supply and demand in the ROK as of 2007. Here “exploitation” denotes extraction of resources, either in the ROK or abroad, with “self-exploitation” meaning resource extraction controlled by Korean firms. “Introduction in Figure 33 means moving resources to the ROK. In 2009, 96.4 percent of energy resources were imported. Primary energy, denoting energy forms before they are processed into the fuels, electricity, and heat used by final consumers, was 42.1 percent crude oil (over 80 percent of it from the Middle East) and oil products in 2009, with LNG 13.9 percent, bituminous coal, mostly for power plants, 25.8 percent, and nuclear energy (as input to 34.1 percent of electricity generation) 13.1 percent. Anthracite coal and new and renewable energy comprised the remainder of less than 5 percent of energy needs. As shown in Figure 4, one of the most notable changes in the last two decades in the ROK energy sector has been the increase in the use of natural gas, with a corresponding decrease in the use of oil. Industry still consumes the majority of final energy use in the ROK, with nearly half of industrial energy use being feedstock materials, mainly the oil product “naptha”, which is used as an input in the petrochemicals industry.

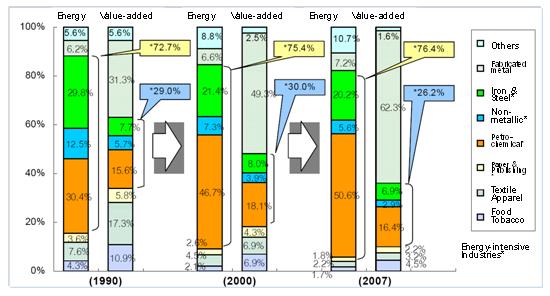

Among industries, as shown in Figure 5, the energy-intensive subsectors (iron and steel, non-metallic products including cement, and petrochemicals) have accounted for about three quarters of energy use and about 30 percent of industrial value added over the past two decades, though within the energy-intensive industries there has been a significant shift in the fractions of energy used toward petrochemicals and away from the other two traditional heavy industries, even as the fractions of value added by heavy industries have remained roughly constant. The largest change since 1990 has been the vast increase in the fraction of industrial value added in the ROK economy that has come from the fabricated metal subsector, including vehicle production, though the fraction of energy consumed in that subsector has risen only modestly. The fraction of industrial energy used and value added produced by the paper and publishing, textile and apparel, and food and tobacco industries has declined over time, and though the fraction of energy used in “other” industries, including, for example, the electronics industry, has increased substantially since 1990, its share of value added has declined.

Figure 3: Flow of Energy Consumption and Production in the ROK, 2009 [6]

Figure 4: Primary Energy Supply by Fuel in the ROK, 1990 – 2009 [7]

Figure 5: Trends in Industrial Energy Use and Value Added in the ROK, 1990 – 2007 [8]

Limited domestic energy resources, a growing manufacturing base in industries highly relevant to nuclear power development, and the desire to develop expertise in nuclear technologies, among other considerations, led the ROK to emphasize nuclear power as an energy supply security measure. 21 nuclear reactors are now under operation, with ongoing expansion expected to result in 28 operating reactors as of 2016. Nuclear generation accounted for 34.1 percent of generation in 2009, and plans call for an additional 6 reactors to be constructed by 2023. By 2010, the ROK’s nuclear capacity and generation ranked sixth among the world’s nations, its fraction of generation produced by nuclear power ranked fourth among the 10 countries with the largest installed nuclear capacity, and the ROK was first by a wide margin among the top 10 nuclear power users when considering its nuclear capacity per unit of land area. [9] The ROK has also been actively promoting nuclear technology exports, including a recent deal to build reactors in the United Arab Emirates. [10]

2.The development of the ROK’s climate and green economy policies

A combination of factors has focused ROK attention on climate and green economy policies in recent years. Over the last century, climate records show that Korea’s temperature has increased by 1.5°C, a rate double the global average (0.7°C), and the temperature in Seoul has increased by 2.5°C. [11] At the same time, the ROK’s high energy consumption and near-complete import dependence are strong inducements to reduce exposure to energy supply security risk by developing domestic resources. The ROK also ranks ninth among the world’s nations in CO2 emissions from fuel combustion and first in the rate at which its GHG emissions grew between 1990 and 2007, more than doubling (increasing by 103 percent) over that span. [12] As of 2007, energy use accounted for by far the largest fraction of the ROK’s GHG emissions, at almost 85 percent, with industrial sector non-energy emissions, including emissions of chlorofluorocarbons from refrigeration systems and other sources, sulfur hexafluoride, perfluorocarbons, and other compounds used as solvents and cleaning agents in the electronics and other industries, and CO2 from cement production, constituting the next largest source of emissions, in terms of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) at somewhat less than 10 percent. [13] Of energy-related sources of GHGs, energy transformation (dominated by electricity generation) was the largest, at over 36 percent, with industry accounting for 32.4 percent.

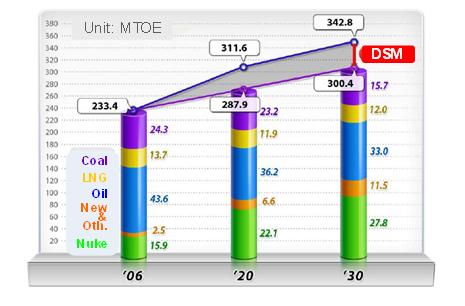

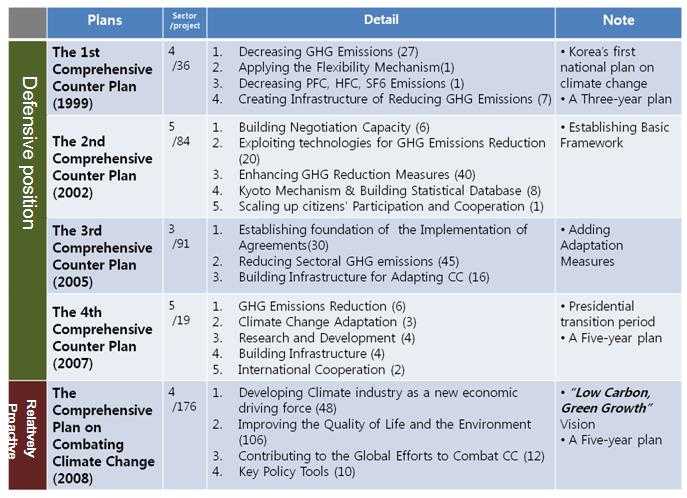

The ROK’s first major set of climate change-related policies was set out in the 1999 draft of the “1st Comprehensive Counter Plan for the Framework Convention on Climate Change (1999~2001) Act on Countermeasures Against Global Warming”. From 1999 through 2007, the ROK’s policy responses related to climate changes tended to be modest in scope, calling for emissions reduction from “business as usual” levels that were not particularly aggressive, and were protective of what was seen as the required increases in energy use to drive a growing economy. Figure 6 shows a summary of the Basic National Plan for Energy as of 2008, in which growth in energy use slows from the levels of the last decade, but overall energy use continues to climb, even with a program of demand-side management (DSM) assumed to be implemented. In 2008, however, and as indicated in Table 1, a major change occurred in the ROK’s climate policies, which shifted from what can be termed a “defensive” position to one that is relatively proactive in addressing climate issues. Though the Lee Myung-bak administration began its tenure with an emphasis on high economy growth, supported by a massive scale of civil engineering development, it second year (2008) saw a sudden turn toward the principles of green growth. This policy change was underscored by presidential announcement, at G20 meetings in Japan and Italy in 2008 and 2009, of the ROK’s plans for significant mid-term GHG emission reduction targets, followed by the release in August 2009 of three scenarios for the ROK’s reduction targets, as produced by The Presidential Committee on Green Growth. Both domestic and international considerations played into the Lee administration’s change in approach. In his speech for the 60th anniversary of national independence, President Lee emphasized green growth as a “new national development paradigm” to allow coming generations to secure a reasonable standard of living, this in contrast to the focus in the previous 60 years on economic growth and export targets, with reductions in GHG emissions as a key indicator of “low carbon green growth”. At the same time, the administration sought to upgrade the ROK’s international image by positioning it as an “early mover” in the green economy transition, thus improving the ROK’s “brand value”, and also by positioning the ROK as a trusted and respected mediator between developing and developed nations, building on the ROK’s status as a (relatively) newly industrialized nation with strong economic links to both the developed and developing world. [14]

Figure 6: Targets of the 2007 ROK Basic National Energy Plan, 2006 – 2030 [15]

Table 1: Evolution of the ROK’s Climate Policies, 1999 – 2008 [16]

The nominal goals of the ROK’s recent climate and development policies are to pursue development of a “new economy coupled with ecology”, in effect creating a virtuous circle between economy and ecology, leading to the a green economy that can be a new growth engine for the ROK. Despite the development of an array of related policies, however, it is too early to discern significant actual green economy progress in the ROK resulting from green growth strategies promulgated during 2009 and 2010. Figure 7 summarizes the three target scenarios of mid-term (2020) GHG emissions reduction announced by the Presidential Committee on Green Growth in 2009. Each represents a considerable departure from the pattern of emissions growth to date and from the BAU (business as usual) case, as the BAU case includes a continued reduction in emissions per unit of economic output that is overwhelmed by the impacts of increasing affluence on per-capita emissions in the ROK, even as the ROK population begins to decline. The most aggressive of the three target scenarios shown in Figure 7, with 2020 emissions 30 percent lower than the BAU case and 4 percent lower than in 2005, was adopted by the ROK government in November 2009, and submitted to the UN in January of 2010. [17]

Figure 7: Mid-term Target Scenarios of GHG Reduction in the ROK [18]

Following President Lee’s speech on the 60th anniversary of National Independence, (August 15, 2008), all government ministries were almost immediately engaged in producing a plethora of policy programs to institutionalize green growth strategy, with competition between ministries not uncommon. In the just over 5 months between August 2008 and January 2009, the following policy programs below (and others) had been put forward, all of which focus on developing new energy and industrial technologies and generating new jobs in the field of green economy:

- The National Energy Basic Plan, and Industrial Development Strategy for Green Energy

- The Basic Plan for the Comprehensive Action against Climate Change

- The Long-term Master Plan for National R&D on Climate Change

- The “Green New Deal”

- Comprehensive Measures for R&D (Research and Development) on Green Technologies

- The Vision and Development Strategy for New Growth Power

The three institutional pillars for Green Growth in the ROK to date have been the establishment of the Presidential Commission on Green Growth in January 2009, the launching of the National Strategy and 5 Year Plan for Green Growth in July of 2009, and legislation of the Framework Act on Low-Carbon Green Growth in December 2009, which went into effect from April 14, 2010. A “5 Year Green Growth Plan” had as its vision elevating the ROK to the 7th-leading “Green Power Country” as of 2020, and to 5th by 2050, based on three strategies and 10 policy directions:

- Strategy 1: climate change adaptation and energy independence, including effective reduction of GHG emissions, reduction of petroleum use and increasing energy independence, and strengthening of the ROK’s adaptation capability against climate change impacts.

- Strategy 2: creation of “new growth power” through green technology development and its utilization to promote new growth power, greening industries and promotion of green industries, deepening of the ROK’s industrial structure, and building the base of the green economy.

- Strategy 3: quality-of-life improvement and upgrading of national status through construction of “green territory”—meaning developing green spaces and the planting of trees and other vegetation throughout Korea, in all settings from urban to rural—and green transportation systems, green reform of the patterns of everyday life, and embodiment of the global model nation of green growth.

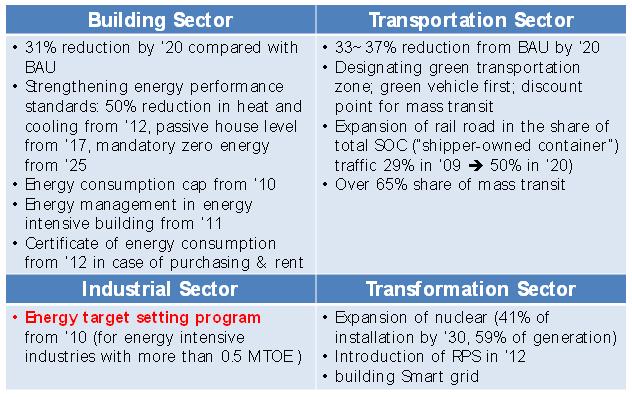

These strategies, are supported by a number of sector-specific goals and targets, including those in Table 2, below for the building, transportation, industrial, and energy transformation sectors, the latter, notably, including and extending the ROK’s goals for expansion of nuclear power.

Table 2: ROK GHG Emission Mitigation Policies [19]

To implement these strategies, the ROK was to spend 107 trillion won (0.107 trillion US dollars) on green growth projects between 2009 and 2014, equivalent to 2% of GDP, with an annual growth rate of 10.2 percent. Of the total green growth investment, however, about 20 percent has been allocated to the “Four Major Rivers” project. [20]

3.Strengths and weaknesses of current green economy policies in the ROK

Although the green energy policies developed during the last few years in the ROK are a notable departure, at least nominally, from earlier policies, it is not clear that the ROK’s policy shift represent a heartfelt conversion to the green economy concepts as defined earlier in this section. Rather, ROK green economy policies to date have tended to focus on establishment of techno-bureaucratic and hardware-oriented institutions for green growth, and have resulted in over-politicization of green growth without building much of a constituency and concern for green growth among the general public. Rather than improvements in the ROK’s environment, the last few years have arguably seen a deterioration of the environmental performance of the national economy. The 2010 Environmental Performance Index released by World Economic Forum rated the ROK 94th of 163 countries, a drop of 43 places since 2008, and the lowest ranking among OECD member nations. [21]

It can be argued that the idea of “green growth” as it is currently being implemented into policy in the ROK is a largely a product of conceptual and ideological degradation of previous meanings of the term. The “two ecos” (economy and ecology) have been at the heart of environmental policy in the ROK since the Kim Dae-Jung Government (1998-2003). Moreover, sustainable development, a higher-level conception of green growth, was instituted as a national priority policy during the Kim Dae-Jung Government and the Roh Moo-Hyun Government (2003-2008). The current advocates of green growth in the ROK misinterpret sustainable development as a West-centered and ecology-biased concept, and thus not suitable for the ROK. There has thus been a process of excluding and discriminating against traditional “green” views, beginning with the degradation of the original Presidential Commission on Sustainable Development (PCSD) into a ministerial commission under the control of Minster of Environment, with its policy review position taken over by the current Presidential Commission on Green Growth (PCGG). Although the PCSD was typical of a governance body representing a wide range of different stakeholder, the PCGG is composed almost entirely of pro-governmental techno-bureaucratic experts representing largely the interests of business community, and excluding traditional green advocates from civil society. This has resulted, essentially, in the representation in green-growth policymaking of just one perspective, being that of advocates for “market-driven green growth”. When the second term of the PCGG commenced in July 2010 and took up the theme of market-driven green growth in its 8th general meeting, suggestions from the industrial and business community were the primary topics debated, with business and allied interests complaining loudly that green growth policies included in proposals offered “only green, no growth”, a reverse of the “only growth, no green” complaints of the environmental community voiced at an earlier stage of the green growth policy debate.

As a result of this shift in how the concept of green growth is put into practice in the ROK, the prospects for reform true reform of the ROK’s environmental performance based on current policies are limited by the paradox of the ROK’s policies of green growth and the green economy. Essentially, at present, these policies emphasize the economy first, and “green” second. The current green growth strategy comprises two key approaches: 1) “low-carbonization”, meaning reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and other environmental pollution to accomplish “defensive green growth”, and 2) “green industrialization”, meaning generation of new growth, power, and jobs for “offensive green growth”. These priorities are reflected in the chapter structure of the “Framework Act on Low-Carbon Green Growth”, which read:

- Promotion of Green Economy and Industry

- Measures for Climate Change and Energy

- Construction of Sustainable Territory and Environment

Operationally, in green growth policy implementation priority has be placed on “the promotion of green economy and industry”, while policies to address climate change and energy security, sustainable land use, and other environmental causes are implemented only to the extent that they support the priority agenda. This reveals the standpoint of the current Korean government that “the economy (growth) is first, green is second”. Such growth, even if considered “green”, is unlikely to result in significant environmental clean-up duel to the following chain of logic. First, the linkage between low-carbon development and green industrialization is “green technology”. Green technologies, in turn are eco-efficient technologies that offer a relative reduction in the amount of environmental pollution per unit economic (resource and energy) input, but do not necessarily imply that the absolute amount of environmental pollution produced by the economy will actually be lower than “business as usual” or some other policy scenario. This further implies that the more green growth based on the principle of eco-efficiency is successfully pursued, the more environmental pollution it generates. As a result, the green economy generated by the ROK’s current green growth policies is likely to end up being neither sustainable nor secure.

The ROK’s “green growth” energy policy may be efficient, but by more standard global definitions of the concept, is rather un-green. Although the ROK’s 2020 target of greenhouse gas reduction is 30 percent of the 2020 BAU emissions estimate, on closer examination the largest portion of green energy included in policies to achieve the target comes from nuclear power, a type of efficient but un-green energy. Nuclear power use is planned to be increased from 36 percent of total 2007 power generation to 59 percent in 2030, in so doing absorbing the largest share of the budget for green technology development (35.9 percent in 2009). This planned nuclear development, however, is not without opposition in the ROK. Within a few years, the ROK’s existing sites for nuclear power plants will have all of the reactor units they can reasonably accommodate, and new plant sites will be required. As of 2010, although almost 90 percent of ROK residents acknowledged the need for nuclear power, a growing number (over 50 percent) were concerned about nuclear safety, and just over a quarter (27.5 percent) of survey respondents found the prospect of new nuclear plants in their own communities acceptable. [22] It is likely, in the aftermath of the Fukushima accident, that a similar survey would find less positive public perceptions of nuclear power in the ROK.

Meanwhile, renewable energy, more typically considered to be a form of green energy, will continue to occupy a minor proportion of the total energy consumption during the forthcoming 50 years or so rising from about 2.7 percent in 2009 to only 6.08 percent in 2020, and only then to a more substantial 30 percent in 2050. Concern for energy independence as manifested in the ROK’s green power policies is not so acute: the ROK’s rate of energy independence (the fraction of energy supplies from domestic sources) excluding nuclear power in 2007 was 3.4%, but rose to 16 percent if nuclear power is considered a domestic resource (though the ROK imports nuclear fuel and licenses some nuclear technologies from other nations). There is no clear target for energy independence based on green energy. As the ROK’s export-oriented economic growth system operates almost entirely through the imports of cheap energy from overseas, the claim of a goal of energy independence by application of current policies appears merely rhetorical in anything but the very long run, and only then with the most aggressive of fuel substitution policies. This likely lack of progress on energy supply security implies that without changing Korea’s economic growth regime, which is sustained by energy efficiency (measured as income per unit energy use) is the lowest (that is, its energy intensity is the highest) among OECD countries, in part because of the concentration of heavy industries in the ROK, substantially improving energy supply security seems infeasible in the ROK under current green growth policies.

A substantial fraction of the ROK’s green growth program is an outgrowth of a bias toward large civil engineering projects as drivers of development. As such, the green growth program features arguably “high-carbon” construction of so-called “green cities”. In this focus, the green growth strategy stems from the civil engineering growth that the current ROK administration, with its renewed (relative to previous administration) emphasis on civil engineering projects development, is inclined to pursue empathically. The Green New Deal program, part of the green growth strategy package, clearly shows this propensity. 64 percent of the total program budget (some 50 trillion won, or nearly half of the total green growth budget) is to be allocated to projects associated with civil engineering work, including the restructuring of four major rivers, generating 910,000 construction jobs out of the total 950,000 jobs estimated to be created by the Green New Deal.

The Four Major Rivers project has been controversial. The Lee Myung-bak government has argued that the project is essential to the green growth movement in Korea and to the “Green New Deal” because it offers significant employment potential while restoring four major rivers. Civil society in Korea, however, has resisted the project because dam construction and dredging are the central elements of the project. These activities, many in civil society argue, will actually kill the four major rivers instead of restoring them [23]. In addition, it is argued that the project actually offers little in the way of employment opportunities, and that the jobs that are created by the project, mostly short-term jobs in construction, do not help to solve what is currently the major unemployment problem in Korea, namely, providing jobs for a highly-educated younger generation. In response to surveys, more than 70 percent of Koreans polled expressed objections to the project. Though the government announced that around 340 thousand jobs will be created by the project, opposing groups argue that only two thousand jobs will be created over the long term. [24]Though the ROK is a highly urbanized society, there is as yet no national target to reduce the total energy consumed and greenhouse gas produced in urban area, though globally cities consume 75 percent of total final energy and produce 80 percent of total GHG emissions. In the ROK, most of the policy efforts planned for the greening of cities tend to be skewed toward constructing new green cities, which are projected to use 30 percent less energy than existing cities consume, rather than improving the energy efficiency of existing built areas. It is unclear from existing plans whether the considerable GHG emissions used in constructing new cities have been factored into the overall carbon budget for the project, or whether GHG emissions savings will somehow be achieved by retiring existing built areas as new cities are built. As a case in point, the pilot project to build a low-carbon city now underway in the district of Keongpyo in Kangneung (Gangneung), is largely a demonstration of new promising green technology and industry, and is understood by local residents to be primarily a new regional development project. [25]

Typical of the ROK’s focus on civil engineering in its green growth program is the government’s plans to supply1 million “green home” as a flagship project for the green economy green economy policies. The green home project is designed to generate new housing technologies and industries in the ROK. The approach used in this project is typical of a top-down government-initiated policy program, in that it expands the supply of environmentally more efficient housing by addressing the “hardware” of the housing stock, but with little effort to involve consumers in greening the patterns of their everyday life. By contrast, in Ireland, a program also called “Green Homes” has a much different focus. [26] Ireland’s program has been initiated by community based organizations, focusing on greening family life as well as community life (for example, through a “green school” component).

The ROK’s green growth strategy, if pursued as currently planned, has a significant probability of running afoul of Jevon’s Paradox, which states that as the efficiency with which a resource is used increases, the use of the resource tends to increase as well, absent measures (such as higher taxes) to prevent same, as consumers find they can afford more of the resource. As a result, it is likely that the more Korea’s green growth is pursued, the more energy the Korean economy will consume, and the more greenhouse gases it will produce, because the green economy policies rely on the intriguing principle of eco-efficiency. Thus, more investment in eco-efficient hardware such as passive housing, green industries and green cities will be likely to end up consuming more total energy and producing more total greenhouse gas than is presently produced. This situation implies that Korea’s future green economy, if shaped by the current green growth strategy will be neither sustainable nor secure.

4.Conclusion: green economy policies in Republic of Korea

The ROK’s green growth strategy, as currently formulated, includes some impressive targets and demonstration projects, but at its heart emphasizes economic growth and national industrial competitiveness rather than being a true plan for “greening” of the Korean economy. As such, the ROK’s current “green” policies are in effect mostly policies for further benefiting existing large ROK industries, including the nuclear and construction industries. As a result, energy and urban security in Korea’s feeble green economy can be secured only insofar as Korea’s e current growth policy regime is either abandoned or recast/reborn into a genuine environmental welfare regime. To do so, more autonomy, and likely more resources, should be granted to the civil society organizations that are best placed to initiate greening of the everyday lives of Koreans in cities and towns at the grassroots levels.

Such a shift calls for analysis of what additional inputs nascent local policies will need to succeed, and for a re-alignment of the goals of development of the green economy with the goals of sustainable development. Such a re-alignment would, among other goals, seek to change patterns of energy consumption in existing cities, pursuing a green economy that makes better use of local resources, and reduces the separation, which is considerable in the ROK, between where energy (especially electricity) is produced and where it is consumed by adopting much more distributed (including renewable) generation. Tools to accomplish such a re-alignment would include energy pricing schemes that favored local electricity generation (such as attractive feed-in tariffs for distributed generation), and promoted energy efficiency (such as rates that increase as a household or business consumes more). Efforts should be made to site power plants closer to consumers so as to more closely relate the impacts of electricity generation and transmission to those that use the power (and reduce the impacts on those that do not). Again, support for distributed generation and “smart grid” development can help.

In addition, green economy strategies in the ROK should seek to improve the affordability of energy services to low-income residents, [27] and acknowledge and seek to take advantage of the fact that after energy consumption reaches a certain level, long since exceeded in the ROK, human welfare, as measured by the Human Development Index, rises very little with increasing energy use. [28] Taking advantage of this pattern, the ROK’s green economy strategy should emphasize increasing the availability of energy services to low-income residents, while at the same time aggressively improving energy efficiency overall so that overall national energy use remains stable or even decreases. In this way, green economy benefits can be shared by all Koreans.

Existing ROK green growth policies tend to use the types of top-down policy strategies that have been traditional in Korea. Achieving true sustainable energy and economic development, founded on the three goals of economic, environmental, and social sustainability, will require a different approach, one that blends considerations of efficiency and energy supply security with low-carbon and low-pollution systems, as well as a commitment to equity and democratic participation. Energy sector approaches such as energy efficiency improvement, renewable energy adoption, use of decentralized energy system, and enhanced participation of residents in energy decisions and the running of energy systems can be combined with other approaches such as changes in land use to promote more balanced and low-impact use of the ROK’s land, enhanced production and use of local food, and lifestyle transformation.

As a part of a sustainable development approach, expanded local energy use may offer several advantages including:

- More energy democracy, providing local residents and citizens’ organizations with opportunities (and responsibilities) to participate in production and consumption decisions;

- A transition to soft path energy, moving from centralized supply-oriented systems to more decentralized, demand management-oriented systems, with an expansion of the use of renewable energy, energy efficiency improvement, and energy conservation;

- Improving energy security through efficiency improvement and renewable energy development, thus responding to peak oil and energy resource depletion problems;

- Improving energy justice in that local communities are more responsible for both the costs and benefits of energy production; and

- Revitalizing the local economy, in that money required for energy production and consumption is circulating within a community to a greater extent, rather than going out of the community (and often, out of the country).

These approaches to achievement of a green economy by means that emphasize sustainable development by design address issues of energy security, urban security, and climate change. These green economy/sustainable development approaches can also, if developed and implemented appropriately, help to improve the ROK’s relationship with the DPRK, and thus help to make progress on resolving the DPRK nuclear weapons situation. First, by addressing sustainable energy and economic development issues on the local level, but with national coordination, processes in the ROK can serve as models for use in the DPRK, and the local emphasis may provide good opportunities for engagement with DPRK counterparts on non-political and grassroots level that is likely to be less threatening to the DPRK than engagement on large, centralized projects. Second, if the ROK is seen to be moving away from nuclear power to less centralized alternatives, that DPRK may feel less pressure to move forward on nuclear energy and nuclear weapons development. Third, as the ROK develops expertise in local power, it will be in a position to share that expertise with the DPRK, including, for example, joint ventures on production of energy and other technologies appropriate for use in both countries, and contributing to the local economies in both nations. Another, reciprocal, interaction is also possible.

The threat of DPRK attack arguably affects, at least in some ways, how the ROK government develops and implements its policies, in that when under threat, any organization tends to concentrate decision-making power, and limit access to information. On a less-theoretical level, the threat of DPRK attack may, for example, argue against the placement of key energy infrastructure in areas near the DMZ, where they would be more vulnerable to attack or sabotage. If progress is made in addressing the DPRK nuclear weapons issue, thereby reducing tensions between the two Koreas, it may help to stimulate the ROK government to promote a less-centralized, more local-based approach to a green economy transition, one more in keeping with the more usual concepts of sustainable development.

[1] United States Central Intelligence Agency (US CIA, 2011), The World Factbook, available as https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html.

[2] This description of Korea’s green growth challenges and initiatives is based on presentations by Sun-Jin Yun of the Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Seoul National University and Myungrae Cho of Dankook University, entitled, respectively, “Energy Security of Cities in Korea” and “Is the Green Economy Secure in Korea?: Dissecting Korea’s Green Growth Strategy”, both presented at the conference “Interconnected Global Problems in Northeast Asia: Energy Security, Green Economy, and Urban Security”, held in Seoul, ROK in October, 2010

[3] Korea Energy Economics Institute (KEEI), Energy Balances downloaded from KEEI’s energy statistics website, http://www.kesis.net/.

[4] Korea Energy Economics Institute (KEEI), 2010, Yearbook of Energy Statistics

[5] Korea Energy Economics Institute (KEEI), 2010, Yearbook of Energy Statistics

[6] Korea Energy Economics Institute (KEEI), 2010, 2010 Energy Info. Korea

[7] Korea Energy Management Corporation (KEMCO), 2010, Handbook of Energy and Climate Change

[8] Korea Energy Management Corporation (KEMCO), 2009, Handbook of Energy and Climate Change

[9] Sources: IEA, 2010, Key World Energy Statistics; National Statistical Office, 2010; Mycle Schneider, Anthony Froggatt, and Steve Thomas, “Nuclear Power in a Post-Fukushima World: 25 Years After Chernobyl Accident,” Worldwatch Institute.

[10] Yonhap News, “The Consortium of Korea Electric Power Corporation won a nuclear power contract of 40 billion dollars,” 12/27/2009.

[11] Won-Tae Kwon, 2011, “Changes in land use resulting from abnormal climate and natural disaster,” Kugto, Vol. 353: 18-29. Some of the increase in temperatures measured in Seoul is doubtless due to the increase in the urban “heat island” effect as the city has grown.

[12] Korea Energy Management Corporation (KEMCO), 2010, Handbook of Energy and Climate Change.

[13] Korea Energy Management Corporation (KEMCO), 2010, Handbook of Energy and Climate Change.

[14] It is possible that this change in the ROK’s position was influenced in part by the status of Ban Ki-moon as the Secretary General of the United Nations. Ban began his term as UN Secretary General in January, 2007.

[15] Office of Prime Minister et al., 2008, The 1st Basic Plan of National Energy (2008~2030).

[16] The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Nyun-Bae Park, Research Professor, Sejong University, ROK, in assembling Table 1

[17] See, for example, Green Growth Korea (2011), “Greenhouse Gas Reduction Target”, available as http://www.greengrowth.go.kr/english/en_subpolicy/en_greenhouse/en_greenhouse.cms.

[18] Source: Presidential Committee on Green Growth (PCGG), 2009, “A plan for mid-term National Greenhouse Gas Emission Target Setting” and PCGG website (as above).

[19] Source: PCGG, 11/04/2009 press release, “Presidential Committee on Green Growth suggests national GHG emission reduction targets”

[20] See the following section for further discussion of the Four Major Rivers project

[21] See, for example, Yale University, “ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE INDEX 2010, South Korea”, Yale University, available at http://epi.yale.edu/Countries/SouthKorea.

[22] Korea Nuclear Energy Promotion Agency, 2010, “Survey Results of People’s Nuclear Awareness in 2010.”

[23] See, for example, Dennis Normile, “Restoration or Devastation?”, Science 26 March 2010: Vol. 327 no. 5973 pp. 1568-1570 (available as http://www.sciencemag.org/content/327/5973/1568).

[24] See, for example, Nocut News, 8/23/2011, “Controversy about employment effect of 4 river project” (in Korean).

[25] For a description of this project, see, for example, Kwi-gon Kim (2010?), “Urban Development Model for the Low-Carbon Green City: The Case of Gangneung”, available as http://www.weitz-center.org/uploads/1/7/0/8/1708801/urban_development_model_kwi_gon_kim.pdf

[26] See, for example, An Taisce and the Ireland Environmental Protection Agency (2011), “What is Green Home?”, available as http://www.greenhome.ie/level1.php?id=programme.

[27] The lowest-income residents of the ROK, the “energy poor”, spend a much higher proportion of their income on energy than higher-income residents, and tend to use lower-quality fuels (Source: Ministry of Economy and Knowledge, 2008, “Reports of Energy Census”)

[28] Source: Martinez and Ebenback, 2008, “Understanding of the role of energy consumption in human development through the use of saturation phenomena,” Energy Policy, Vol. 36: 1430-1435; UNDP, 2004, “World Energy Assessment”; Amie Gaye, 2008, “Access to Energy and Human Development,” UNDP’s Human Development Report 2007/2008.

IV. Nautilus invites your responses

The Northeast Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this essay. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.