VINCE SCAPPATURA AND RICHARD TANTER

AUGUST 4, 2025

I. INTRODUCTION

Vince Scappatura and Richard Tanter use previously unreported declassified CINCPAC Command Histories and Australian cabinet papers to examine the decisions by the Australian government under Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser in the early 1980s to allow the deployment of USAF B-52 Stratofortress bombers. The authors situate both Australian deployments in increasingly urgent U.S. requirements for post-Vietnam training of aircrews to meet performance standards for nuclear penetration SIOP missions on the one hand, and Middle Eastern and western Indian Ocean surveillance requirements triggered by a combination of loss of regional bases and the increasing presence of Soviet naval and air forces in the Indian Ocean. Australian cabinet papers demonstrate a determination by Fraser and his cabinet to balance the alliance advantages of hosting U.S. strategic platforms, with an attempt to control one dimension of reliance on nuclear alliance through a successful rejection of the otherwise global U.S. policy of neither confirming nor denying the presence of nuclear weapons. Fraser’s NCND policy was a unique, and uniquely successful, example of democratic managerialist approach to controlling one dimension of reliance on nuclear alliance – and one both never repeated and as necessary today as more than four decades later.

The complete Special Report is available here (PDF 5 MB). The press kit and related materials for the Nuclear-capable B-52H Stratofortress bombers project are here

Historical and contemporary policy aspects of this study are developed at greater length in two Nautilus Special Reports by Vince Scappatura and Richard Tanter, viz, Nuclear-capable B-52H Stratofortress strategic bombers: a visual guide to identification, Nautilus Institute Special Report, 26 August 2024 (241 pp.; 11.2 MB] and Undermining Rarotonga: Australia’s new nuclear posture (forthcoming).

Vince Scappatura is Sessional Academic in the Macquarie School of International Studies at Macquarie University, and author of The US Lobby and Australian Defence Policy, Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2019. He recently published ‘B-2 Bomber Strikes in Yemen and their Significance for Australia’, Nautilus Institute Special Report, 11 November 2024.

Richard Tanter is Senior Research Associate at the Nautilus Institute, and co-author, with Desmond Ball, of Japan’s Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Ground Stations: A Visual Guide, Nautilus Institute Special Report, 6 August 2015. He recently published Does Pine Gap place Australia at risk of complicity in genocide in Gaza? A complaint concerning the Australian Signals Directorate to the Inspector General of Security and Intelligence, 27 March 2024.

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to Peter Hayes, David Lee and Stephan Frühling for comments on earlier drafts. We are particularly grateful to Peter Hayes for access to the Nautilus Institute FOIA Documents collection, and to Stephan Frühling for his close and constructive engagement with large parts of the argument. Of course, none of the readers are responsible for errors that may remain. We are also grateful to Anna Hood for helpful advice; to Philp Dorling, John Hughes, Tim Rowse and Michael Hamel-Green for assistance with finding resources; and to the New Zealand National Library for allowing us access to Robert E. White’s invaluable and now rare study on Nuclear Ship Visits: Policies and Data for 55 Countries, (Dunedin: Tarkwode Press, 1989). We are very grateful to Chips Mackinolty and Ann Stephen for permission to reproduce their two images, each properly judged iconic today. We are grateful to the National Archives of Australia, SSM Herb Friedman, and Ron Cuskelly for permission to reproduce images. Some images reproduced in this work appeared originally in United States Department of Defense and armed services sources. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement. Images reproduced from Australian Department of Defence and armed services sources is subject to Defence Department copyright.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

Banner image: Ann Stephen, 1982; image based on Arthur Streeton, ‘Land of the Golden Fleece’, (1926); image courtesy of the artist.

II NAPSNET SPECIAL REPORT BY VINCE SCAPPATURA AND RICHARD TANTER

B-52S IN AUSTRALIA IN 1979-1991 AND THE NUCLEAR HETERODOXY OF MALCOLM FRASER

AUGUST 4, 2025

Summary

On 11 March 1981, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser addressed the House of Representatives to announce two U.S. B-52 bomber missions involving Australian airspace and military bases. These operations – BUSY BOOMERANG, a low-level terrain-avoidance training exercise, and GLAD CUSTOMER, a maritime surveillance mission over the Indian Ocean utilising RAAF Base Darwin – formed part of a broader U.S. strategic response to Soviet expansionism and the loss of regional basing options, particularly following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Iranian Revolution. Fraser’s statement marked the culmination of nearly a year of intense and confidential negotiations with Washington, and it represented a significant turning point in Australia’s role within U.S. global military planning.

Fraser’s announcement was historically significant because it openly defied the longstanding U.S. policy to ‘neither confirm nor deny’ (NCND) the presence of nuclear weapons on its military platforms. Instead, Fraser insisted on four key principles that asserted Australian sovereignty and introduced a rare degree of transparency into Australia-U.S. strategic arrangements: (1) B-52s operating in Australian territory would not carry nuclear or conventional weapons; (2) the Australian government would retain the right to approve any change in the mission parameters; (3) Parliament would be informed of any such changes; and (4) the United States would publicly consent to these arrangements.

This position was not only unprecedented in Australia, but also unique globally. No other host country of U.S. nuclear-capable platforms had previously succeeded in defying U.S. NCND policy while extracting a public commitment from the U.S. about the non-introduction of nuclear weapons. This remains the case to the present.

The BUSY BOOMERANG mission, described domestically in Australia in benign terms as ‘low-level navigation training,’ was in reality a highly demanding and hazardous terrain-avoidance exercise conducted at night at speeds up to 740 kph and altitudes as low as 100 metres. This training aimed to prepare U.S. Strategic Air Command for nuclear offensive operations that could penetrate Soviet air defences.

The GLAD CUSTOMER maritime surveillance mission arose from a deteriorating U.S. strategic position in the Indian Ocean during the late 1970s. In response to increasing Soviet naval capabilities and the loss of access to Middle Eastern bases, the U.S. accelerated plans to deploy B-52s for surveillance and interdiction missions globally, with Australia playing a key role.

Despite opposition from civil society, the media, and the Australian Labor Party, much of the criticism lacked a nuanced understanding of the strategic imperatives driving U.S. requests for access. Notably, although then Opposition Leader Bill Hayden strongly criticised the arrangement – citing concerns about Australia’s subservience to U.S. interests – the subsequent Hawke Labor government not only maintained but expanded both B-52 missions.

To the best of public knowledge, nuclear weapons were never introduced into Australia under either mission. Nevertheless, there was little public awareness that B-52 low-level terrain-avoidance training was inherently tied to U.S. nuclear war planning under the U.S. Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP). Moreover, the B-52 missions in Australia were not isolated cases but part of a broader strategy by U.S. Pacific Command to secure access to bases across the region, including in Japan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Thailand, and South Korea – developments not widely known in Australia at the time, and likely not fully understood even at senior political levels.

Fraser’s principled rejection of the NCND policy stands as a rare and bold assertion of national sovereignty within the framework of a close military alliance. While subsequent Australian governments have expressed ‘understanding and respect’ for U.S. NCND policy, none have repeated Fraser’s demand for explicit sovereign control over such nuclear-related decisions. His nuclear heterodoxy offers a compelling model of what a U.S. ally can achieve within the confines of a nuclear alliance. That achievement ought to replicable by U.S. allied host states today.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. B-52s in Australia – the American story

2.1 Introduction

2.2. The low-level terrain avoidance training mission

2.2.1 The region-wide demand for access to terrain-avoidance training routes

2.2.2 Papua-New Guinea

2.2.3 The Philippines

2.2.4 Republic of Korea

2.2.5 Japan

2.3 The maritime surveillance mission

2.3.1 Strategic drivers

2.3.2 Limitations of P-3 Orion maritime surveillance

2.3.3 B-52 maritime surveillance, attack support and interdiction roles

2.3.4 An open question: did GLAD CUSTOMER maritime surveillance operations in the late 1980s include interdiction capability?

2.4 Summary

3. B-52s in Australia in the 1980s – the Australian story

3.1 Introduction

3.2 The first agreement: BUSY BOOMERANG, February 1980

3.3 The development of the final Australian negotiating position on B-52 missions – the Cabinet papers, July – September 1980.

3.4 The second agreement: 11 March 1981 – B-52 staging operations through Darwin, and guidelines and principles for all B-52 operations

3.5 The third Fraser agreement – BUSY BOOMERANG DELTA, October 1982

3.6. Routes and frequency of the Australian B-52 missions

3.6.1 Routes – BUSY BOOMERANG – February 1980-1990

3.6.2 Routes – BUSY BOOMERANG DELTA, 1982-1990

3.6.3 Simulated bombing and minelaying in CINCPAC terrain-avoidance training.

3.6.4 Routes – GLAD CUSTOMER, 1981 – 1991

3.6.5 Frequency – terrain-avoidance training and bombing simulation missions

3.6.6 Frequency – GLAD CUSTOMER

3.7 Labor and the B-52s

3.7.1 The Labor response to the February 1980 agreement

3.7.2 The Labor response to the March 1981 Fraser statement

3.7.3 ‘Cast iron assurances’: B-52s under Labor in office, 1983-1991

4. Fraser’s nuclear heterodoxy and its fate

4.1 Introduction

4.2. The dimensions of Fraser’s nuclear heterodoxy

4.3. Fraser and nuclear weapons

4.4. Fraser: a true Menzies man?

4.5. Intimations of a new sovereignty? Flawed predictions of future alliance flexibility

4.6 Was the 1981 Fraser agreement a uniquely successful repudiation of neither confirm nor deny?

4.6.1 Robert McNamara: ‘the need to develop tacit understandings’

4.6.2 Strategic cover-ups: how the United States maintained nuclear access amidst host nation prohibitions

4.6.3 The limits of trust in nuclear diplomacy

4.7 Standing apart: Explaining Malcolm Fraser’s successful challenge to the global NCND norm

4.8 The fate of Fraser’s nuclear heterodoxy

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cabinet documents cited from National Archives of Australia

Appendix 2. Australian B-52 Stratofortress deployment decisions and events

Appendix 3. B-52 overflights and landings, 1980-1991 – Australian official data

Appendix 4. Guidelines and Principles, Decision No 12737 Provision of staging facilities in Australia for U.S. B52 aircraft, 11 September 1980.

Appendix 5. CINCPAC Command Histories in the Nautilus Institute archives

Appendix 6. Countries with bans and visits by nuclear-armed or nuclear-powered ships

1. Introduction

Late in the afternoon of Wednesday, 11 March 1981, the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser rose in the House Representatives to make a major statement on defence issues, ushering in a new stage in Australia’s alliance relations with the United States.[1] A year earlier, a matter of weeks after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Fraser’s Liberal-National Country Party coalition cabinet had authorised U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortress operations over Australian territory to carry out low-level terrain avoidance training flights over far north Queensland.[2]

Fraser’s 11 March 1981 Ministerial Statement on Staging of B52s through Australia for Sea Surveillance in the Indian Ocean and for Navigation Training announced a second and more strategically significant mission, involving U.S. B-52s not only overflying Australia for low-level navigation training, but also using Australia’s northernmost air base to launch maritime surveillance operations over the Indian Ocean.

The B-52 low-level navigation training mission, codenamed BUSY BOOMERANG by the United States authorities, was aimed at remedying deficiencies that has emerged in the Vietnam War in the capabilities of U.S. Air Force strategic bomber crews to carry out low-level nuclear penetration missions of the Soviet Union and China required under the Single Integrated Operational Plan for nuclear war. Codenamed GLAD CUSTOMER by the Pentagon, the maritime surveillance mission staging through Darwin originated in wider U.S. plans to counter Soviet regional expansion and possible threats to western control over Middle Eastern oil sources in the aftermath of both the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

After almost a year of intense and sensitive negotiations in the last year of the Carter Administration and the first months of the Reagan Administration, Fraser’s ministerial statement announced a set of guidelines and principles for both Australian B-52 missions that amounted to a globally significant challenge to U.S. demands that governments hosting deployment of nuclear-capable aircraft comply with the U.S. policy of neither confirming nor denying the presence or absence of nuclear weapons (NCND).

Both the BUSY BOOMERANG B-52 terrain avoidance training mission and the GLAD CUSTOMER maritime surveillance mission initiated by the Fraser government were subsequently maintained to at least the end of the decade by the Hawke Labor government. This decade-long deployment constituted the first of four main phases in Australia’s half century of almost continuous close involvement with U.S. B-52 Stratofortress operations from 1979 onwards.[3]

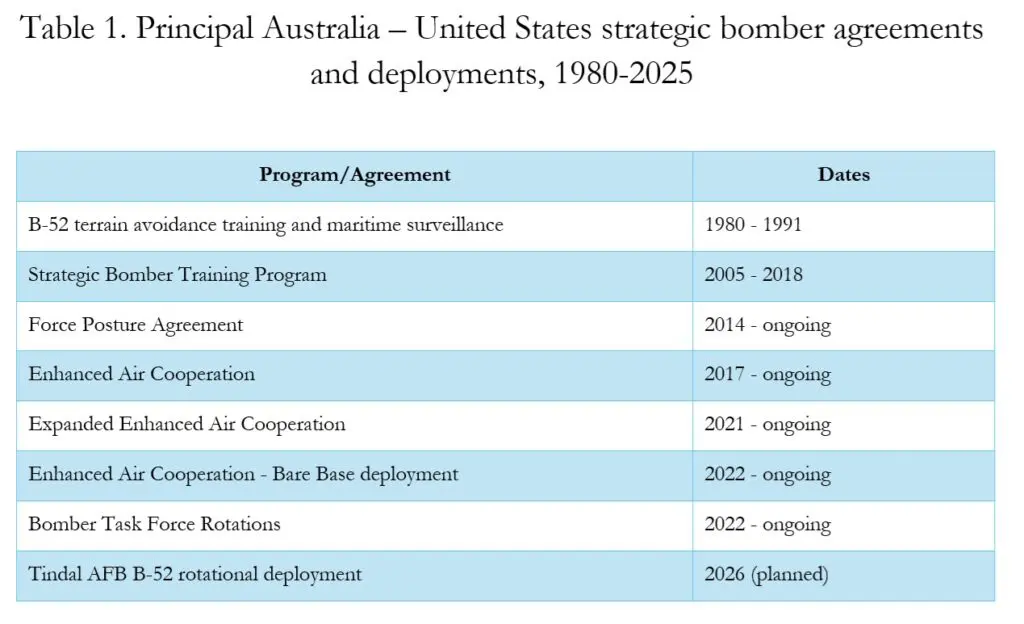

The first phase, which forms the focus of this study, centres on the decade-long low-level terrain-avoidance training mission and the Indian Ocean maritime surveillance missions. The second phase began in earnest in November 2005 with the commencement of the United States Strategic Bomber Training Program centred on the use of Delamere Air Weapons Range in the Northern Territory for live conventional bombing practice and increasing interoperability capability. A third phase incorporated more frequent bomber deployments to a larger array of northern air bases with the announcement of the Enhanced Air Cooperation initiative under the framework of the 2014 Australia-United States Force Posture Agreement. The fourth phase began with the announcement in 2022 of the construction of a dedicated set of USAF infrastructure facilities at RAAF Base Tindal near Katherine centring on the rotational deployment of up to six USAF B-52H Stratofortress aircraft.

With each new phase, Australian governments not only expanded the scope of permissible strategic bomber operations but jettisoned critical limitations that had been imposed on prior deployments under the framework established by the Fraser government and that served to maximise Australian sovereignty and maintain a degree of democratic transparency and accountability.[4]

When Prime Minister Fraser announced the guidelines and principles that governed the first phase of B-52 bomber deployments to Australia in March 1981 he did so explicitly within the framework of maintaining Australia’s national sovereignty, even though this meant breaking the worldwide U.S. policy to neither confirm nor deny the presence of nuclear weapons on board U.S. aircraft:

‘The Australian Government has a firm policy that aircraft carrying nuclear weapons will not be allowed to fly over or stage through Australia without its prior knowledge and agreement. Nothing less than this is consistent with the maintenance of our national sovereignty.’[5]

In addition to this commitment to national sovereignty, Fraser insisted on a degree of democratic transparency and accountability concerning war powers when he declared in parliament that should his government accept any future request from the United States to carry out any other category of B-52 operations, including nuclear operations, the House would be informed of the agreement and provided with the opportunity to debate it:

‘I also indicate to the House that if the agreement of the Government of Australia were sought and given for any other category of operations I, or the Minister, would advise the House at the time of its being done. The Parliament would be able to debate that agreement if it wished to do so.’[6]

The key principles regulating the BUSY BOOMERANG and GLAD CUSTOMER missions developed by the Fraser government can be summarised as follows:

- Deployed B-52 strategic bombers must not carry nuclear or conventional weapons, i.e. they must be unarmed and carry no bombs;

- The knowledge and consent of the Australian government is required before any change in the mission type and/or arms carried;

- The Australian government will inform parliament of any change in mission type and/or arms carried; and

- The U.S. agrees to consent to these arrangements in public.

This set of principles was unprecedented and never repeated by any host governments of nuclear-capable USAF aircraft, in Australia or elsewhere.[7]

In Australian political histories, these decisions by the Fraser government have been usually presented in terms of Fraser’s ardent Cold War views on Soviet expansionism, particularly after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979, his concern to bind the United States more closely to the defence of Australia by offering increased naval and air base access to the U.S., and his support for a US-led nuclear world order during the post-détente era then emerging.

While undoubtedly each of these elements of Fraser’s views on Australian foreign policy and defence played a part in initiating over four decades of an almost continuous presence of B-52s in Australia, this received narrative is misleading in six important respects:

- Fraser’s nuclear heterodoxy, characterised by his insistence that the United States publicly acknowledge that BUSY BOOMERANG flights would be ‘unarmed and carry no nuclear weapons’, has been largely overlooked by historians of Australian foreign policy. And while rare exceptions to the seven decade global history of U.S. neither confirm nor deny doctrine have been occasionally noted in studies of U.S. nuclear policy, Fraser’s nuclear heterodoxy was unique amongst leaders of countries hosting U.S. nuclear-capable aircraft, both during the Cold War and subsequently.

- In reply to Fraser’s March 1981 Ministerial Statement, the Australian Labor Party opposition launched a vitriolic parliamentary attack, resting in part on a need to avoid what opposition leader Bill Hayden termed ‘a master-servant relationship’ with an ally, and on what Hayden’s deputy viewed as ‘a mistake on their [the U.S.] part’ by publicly acknowledging that B-52 flights over Australia would be unarmed and carry no bombs.[8] However, both Australian B-52 missions were continued after Fraser left office without interruption under the successor Hawke Labor government between 1983 and 1991, with the 1981 agreement described in 1986 by the Labor Defence Minister, Kim Beazley, as a ‘cast-iron’ guarantee of the aircraft being unarmed and carrying no bombs.[9]

- Australian official, media and academic reporting and discussion of the BUSY BOOMERANG mission always referred to the mission in somewhat innocuous terms as ‘low-level navigation training’. U.S. military internal discussions, on the contrary, used the more accurate, if diplomatically unpalatable, term of ‘terrain-avoidance’ training, with the aim of limiting domestic host country concern about the obvious dangers of bomber flights over mountainous terrain at a height of 100-150 metres and at speeds up to 740 kph, often at night.

- U.S. need for access to Australia for both the terrain-avoidance low-level training mission and the Indian Ocean maritime surveillance mission was a response to significant deterioration in the 1970s in U.S. strategic capability in two distinct respects:

- On the one hand, the vulnerability of B-52s in high level bombing operations confirmed by Soviet-supplied advanced air defence systems during the Vietnam War required the perfection of technically demanding low-level terrain-avoidance strategic penetration capability to fulfil the requirements for viable nuclear attack by U.S. bombers on the Soviet Union and China under successive iterations of the Single Integrated Operational Plan.

- On the other, initial U.S. planning in the mid-1970s for a long-range maritime surveillance and interdiction role for B-52s was accelerated by an unprecedented Soviet naval presence in the Indian Ocean, combined with the geopolitical and basing consequences of the Iranian revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

- Neither the B-52 terrain-avoidance low-level training mission nor the Indian Ocean maritime surveillance mission took place in Australia alone: each was part of U.S. global military planning.

- The U.S. programs to obtain access to Australia for B-52 terrain-avoidance training and maritime surveillance operations were part of a region-wide coordinated campaign by U.S. Pacific Command over more than a decade involving sustained diplomatic pressure to obtain B-52 access rights from Australia, Japan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, South Africa, South Korea, and Thailand.

- Responding to increases in the scale, capabilities and geographical reach of the Soviet blue-water navy and naval aviation in the 1970s, B-52 maritime surveillance operations commenced in the western Atlantic in 1975, and extended into the north Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East, until the loss of access to suitable Middle Eastern bases at the end of the decade heightened the requirement for Australian base access.

- The two 1980s B-52s missions in Australia, while quite distinct, were similar insofar as both were physically and mentally demanding on pilots, technically difficult for aircrew to attain the required level of proficiency, and frequently dangerous. However, the two missions were responses to quite distinct U.S. strategic requirements and organisational imperatives, resulting in dissimilar operational characteristics, and quite different relationships to the question of nuclear armament.

- The maritime surveillance mission was one part of the complex suite of non-nuclear-armed B-52 missions that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, mainly responding to the requirements of the Indochina war and shifting geopolitical requirements. By 1986 the B-52 maritime surveillance mission evolved into a surveillance and interdiction mission, with B-52 squadrons based in Maine and Guam equipped with Harpoon antiship missiles with conventional explosive warheads.

-

- The core objective of the terrain avoidance training mission was to ensure that Strategic Air Command aircrews were capable of meeting the unique and demanding operational standards of the low-level strategic offensive penetration mission for B-52s under the SIOP for nuclear attack in the face of modern air defence systems. Serious accidents in the early stages of the terrain avoidance training program meant that the aircraft should not carry nuclear weapons, but the training itself was inherently tied to offensive nuclear operations essential to U.S. success in nuclear warfighting.

This study of Fraser’s nuclear heterodoxy proceeds as follows.

Chapter two situates the deployment of B-52 bombers to Australia within the broader context of U.S. strategic planning in the Pacific and Indian Oceans during the late Cold War. Drawing on declassified Commander in Chief Pacific Command (CINCPAC) histories, it demonstrates how the two B-52 missions in Australia served multiple U.S. military objectives – from nuclear and conventional strategic penetration training to surveillance and maritime interdiction – while disclosing key, previously classified operational details.

Chapter three examines the two B-52 missions from the Australian perspective, detailing the negotiations, agreements and domestic debates surrounding the deployments and the evolving strategic context of the Cold War that framed them. It highlights the Fraser government’s success in imposing stringent conditions on U.S. access to Australian airspace and bases, notably securing public U.S. confirmation that no nuclear weapons would be introduced.

Chapter four examines the legacy of Fraser’s unique and assertive stance on nuclear weapons, particularly his rejection of the global U.S. NCND policy. While successive Australian governments have continued to express ‘understanding of and respect for’ U.S. NCND policy, Fraser’s approach remains an exceptional assertion of national sovereignty, transparency and accountability.

The complete Special Report is available here (PDF 5 MB). The press kit and related materials for the Nuclear-capable B-52H Stratofortress bombers project are here

III. ENDNOTES

[1] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, Staging of B52s through Australia for Sea Surveillance in the Indian Ocean and for Navigation Training: Ministerial statement, 11 March 1981, 664-666, (Malcolm Fraser, Prime Minister). The ministerial statement and subsequent parliamentary debate is available at CPD, House of Representatives, 11 March 1981, 664-684.

[2] Department of Defence, Defence Report 1980, AGPS, Parliamentary Paper No. 174/1980, p. 6, at https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1928178155/view?partId=nla.obj-1929030610; Department of Defence, ‘US Air Force B-52 Flights’, Defence Press Release No. 9/80, 18 February 1980, at https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/media/pressrel/HPR08005951/upload_binary/HPR08005951.pdf

[3] The last currently available evidence of B-52 ‘crew training’ operations related to the BUSY BOOMERANG and the GLAD CUSTOMER missions is a brief statement by Defence Minister Robert Ray to the Australian Senate in November 1991. Ray does not mention either mission continuing. (See Appendices 2 and 3.)

[4] These principal phases have usually overlapped to some degree, and throughout the whole period since 1980, B-52s have also participated in Australian-US military exercises, both on a regular schedule of multilateral exercises, and on an ad hoc basis. For further discussion see Section 4.8 below.

[5] CPD, House of Representatives, 11 March 1981, 666, (Malcolm Fraser, Prime Minister).

[6] CPD, House of Representatives, Questions without notice: B52 Bombers, 12 March 1981, 703.

[7] See the discussion of this issue in Vince Scappatura and Richard Tanter, Nuclear-capable B-52H Stratofortress strategic bombers: a visual guide to identification, Nautilus Institute Special Report, 5 August 2024, pp. 51-53 and Appendix 5, at https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/nuclear-capable-b-52h-stratofortress-bombers-a-visual-guide-to-identification/.

[8] CPD, House of Representatives, 11 March 1981, 666-670, (Bill Hayden and Lionel Bowen).

[9] ‘No warheads on B-52s: Beazley’, Canberra Times, 17 January 1986.

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.