by Peter Hayes and Richard Tanter

November 13, 2012

This report was originally presented at the New Approach to Security in Northeast Asia: Breaking the Gridlock workshop held on October 9th and 10th, 2012 in Washington, DC. All of the papers and presentations given at the workshop are available here, along with the full agenda, participant list and a workshop photo gallery.

Nautilus invites your contributions to this forum, including any responses to this report.

CONTENTS

I. Introduction

II. Report by Peter Hayes and Richard Tanter

III. References

IV. Attachments

V. Nautilus invites your responses

Hayes and Tanter offer a brief overiew of the benefits of establishing a Nuclear Weapons Free Zone in Northeast Asia. They then evaluate critical elements and issues associated with establishing such a zone, including monitoring and verification, membership, obligations, enforcement and the legal and political issues surrounding both North Korea and Taiwan.

Peter Hayes is the Executive Director of the Nautilus Institute and Richard Tanter is an Associate of the Nautilus Institute.

II. Report by Peter Hayes and Richard Tanter

Key Elements of Northeast Asia Nuclear-Weapons Free Zone (NEA-NWFZ)

by Peter Hayes and Richard Tanter

1. Purpose: A nuclear weapons-free zone (NWFZ) is a treaty, affirmed in the Nuclear Non Proliferation Treaty, whereby states freely negotiate regional prohibitions on nuclear weapons.[1] Its main purposes are to strengthen peace and security, reinforce the nuclear non-proliferation regime, and contribute to nuclear disarmament. A NEA-NWFZ would provide a stabilizing framework in which to manage and reduce the threat of nuclear war, eliminate nuclear threats to NNWSs in compliance with their NPT-IAEA obligations, and facilitate abolition of nuclear weapons. (It would apply to nuclear weapons only, not to other “WMD.”) It would also restrain and reverse the DPRK’s nuclear-armament; build confidence that nuclear weapons will not be used either for political coercion or to fight wars; and reassure non-nuclear weapons states that they are secure, thereby deepening commitment to non-nuclear weapons-status. In a NEA-NWFZ, US Forces Korea and a reconstituted UN Command [2] might become a pivotal [3] rather than a partisan deterrent, thereby creating an enduring geostrategic buffer between the two Koreas, and between China and Japan. [4]

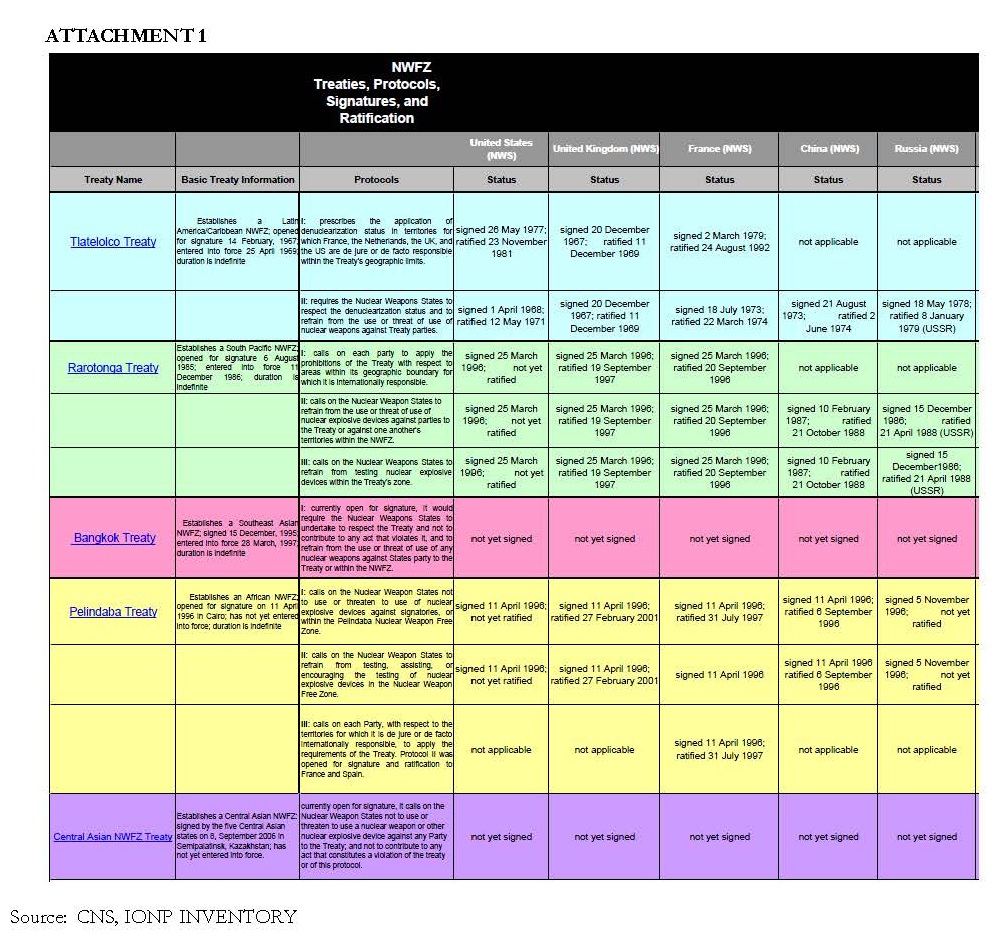

2. Differentiated Obligations in a NWFZ Treaty: Non-Nuclear Weapons States (NPT NNWS) undertake to not research, develop, test, possess, or deploy nuclear weapons, and to not allow nuclear weapons to be stationed on their territory. [5] Nuclear-Weapons States (NPT NWSs) give negative security assurances to not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against the NNWSs party to and in compliance with the NWFZ treaty. [6] (See Attachment 1).

3. Membership: In early proposals [7], 3 NWS (US, China, FSU then Russia) + 3 NNWS (2 Koreas, Japan) were proposed as parties. In 2010, Nautilus proposed a 3+2 version (starting with ROK and Japan only, leaving an open door for the DPRK to join later or collapse into the zone). With the Six Party Talks moribund, it seems sensible for all five NPT-NWSs to join, and at least 4 NPT-NNWSs join at the outset (Japan, ROK, Canada, Mongolia); and possibly DPRK in a contingent status (explained below). This “5 + 4.5,” later “5+5” (ignoring Taiwan, see below) model of a NEA-NWFZ takes time (but not without limit) to integrate fully the DPRK.

4. Monitoring and Verification (M&V): At minimum, all NNWS in a NEA-NWFZ should accept the IAEA Additional Protocol. Plutonium-based fuel cycles may require more stringent transparency in real-time than current safeguards systems allow to preserve a meaningful diversion-detection to response-time ratio. Specific M&V provisions would be needed during and after dismantlement in the DPRK.[8] Specific arrangements will be needed to control DPRK nuclear-capable personnel. Challenge inspections might be built into the NWFZ treaty itself. Non-intrusive inspections of transiting ships and aircraft might use state-of-the-art anti-terrorist monitoring techniques at airfields and in ports but not in innocent oceanic or aerial transit. The treaty may want to invite parties to adopt more stringent inspection arrangements as technology evolves. For example, parties to a NWFZ could create a regional nuclear forensics network and database to control non-state actor nuclear proliferation.

5. Enforcement: The existing toolkit of sanctions, interdiction, and coercive diplomacy combined with engagement is appropriate in maintenance of a NEA NWFZ. Nuclear threats against non-NNWSs by nuclear armed states or by NPT-NWSs should be met in accordance with the 1994 UNSC resolution whereby the NWSs undertook to respond to “nuclear aggression” against NNWSs. A NWFZ will place the legal onus on all NWSs party to the NWFZ to respond, not merely those in bilateral alliances (US-ROK, US-Japan, PRC-DPRK).

6. North Korea: As a declared nuclear-armed state, the DPRK’s nuclear aggression [9] presents a major obstacle, albeit primarily political-psychological, rather than military, to realization of a NEA-NWFZ. However, the main reason to establish a NEA-NWFZ is not just to respond to the DPRK, but also to address the proliferation potential of Japan, the ROK, and Taiwan, and to create a stabilizing framework in which to manage strategic deterrence between the NWSs. The DPRK should not be allowed to shape the strategic environment. Rather, a sound strategic environment should be created that shapes the DPRK’s choices.

In a legal sense, there are two ways to deal with the DPRK in a NEA-NWFZ treaty. The first is to simply leave the door open for NNWSs to join the treaty. Thus, if only Japan, the ROK, Canada, and Mongolia were to sign at the outset, the DPRK could later join after denuclearization (or collapse into the ROK, making the issue moot). More desirably, the DPRK could join the NEA-NWFZ treaty at the outset, but not waive the provision that the treaty only come into force when all parties have ratified it, while the other parties would waive this provision. [10] The DPRK thereby would reaffirm its commitment to become a NNWS in compliance with its NPT-IAEA obligations, but would take time to comply fully. The other NNWSs could set a time limit for this to happen and reserve the right to abandon the treaty if the DPRK has not denuclearized sufficiently by that time. Concurrently, the NWSs (hopefully all of them, not just the US) would qualify their guarantees to not use nuclear weapons to attack the NNWSs party to the treaty so as to specifically exclude the DPRK from the guarantee, or would calibrate their guarantee to the extent that it has come into full compliance.

In this manner, the DPRK’s nuclear armament, such as it is, would not be recognized as legitimate in any manner; the standards that it must meet when denuclearized would equal those for all non-NNWSs in the NWFZ, including M&V requirements; and most important, the DPRK would be offered a legally binding, multilateral guarantee by all the NWSs that it will not face nuclear threat or the use of nuclear weapons against it. Based on history and its weak strategic situation we judge this benefit to be of great significance to the DPRK. The only way to find out how valuable this guarantee would be to the DPRK is to engage it.

7. Taiwan: Taiwan can declare that it will fulfill the NNWSs’ obligations in NEA NWFZ treaty. China can declare that its commitment covers Taiwan as part of China (NWSs have made such declarations in other NWFZs with regard to trust territories). A NWFZ that de facto includes Taiwan could reduce DPRK leverage on China and the US via the threat it might share nuclear weapons with Taiwan; or by the threat of attack on the ROK in the midst of a Taiwan Straits crisis involving a US-China confrontation.

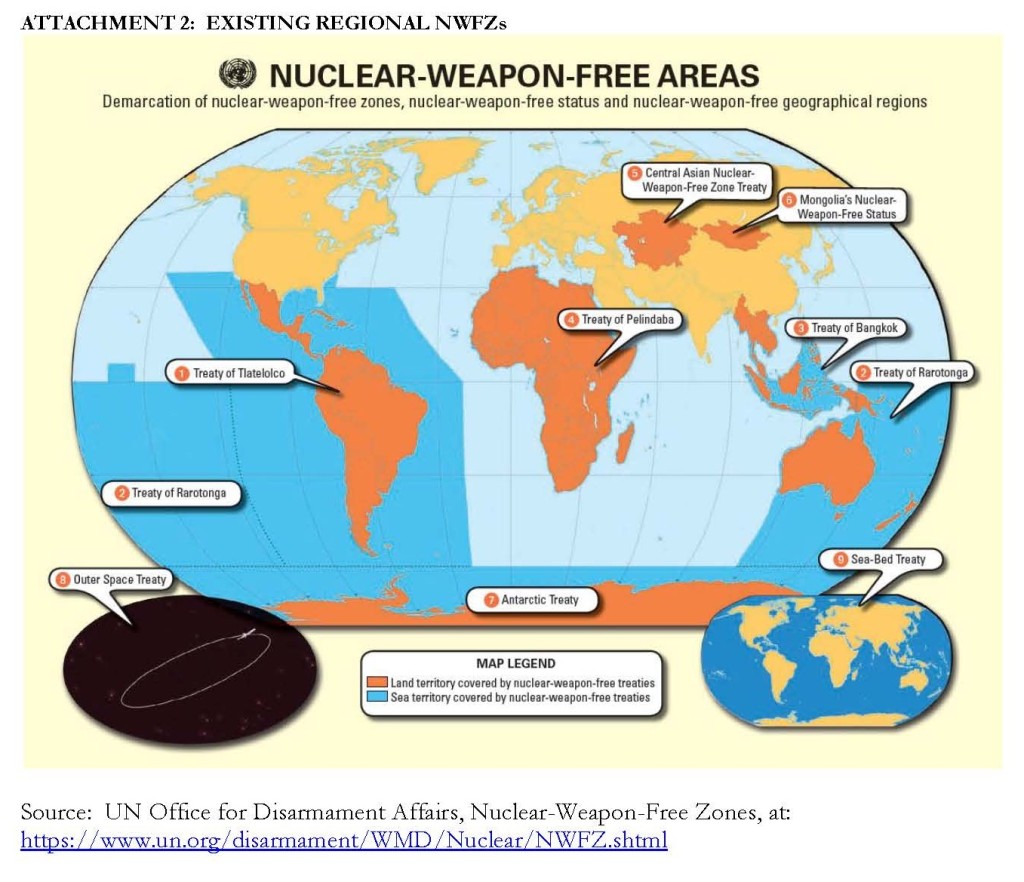

8. Precedents and Linkages: Six NWFZs exist today (Attachment 2). [11] A Middle East (ME-NWFZ is under consideration. NEA’s reliance on Iranian oil and the DPRK’s potential nuclear transactions with Iran links NWFZs in these regions. A NEA-NWFZ that includes the DPRK and reinstates its denuclearization would facilitate a ME-NWFZ.

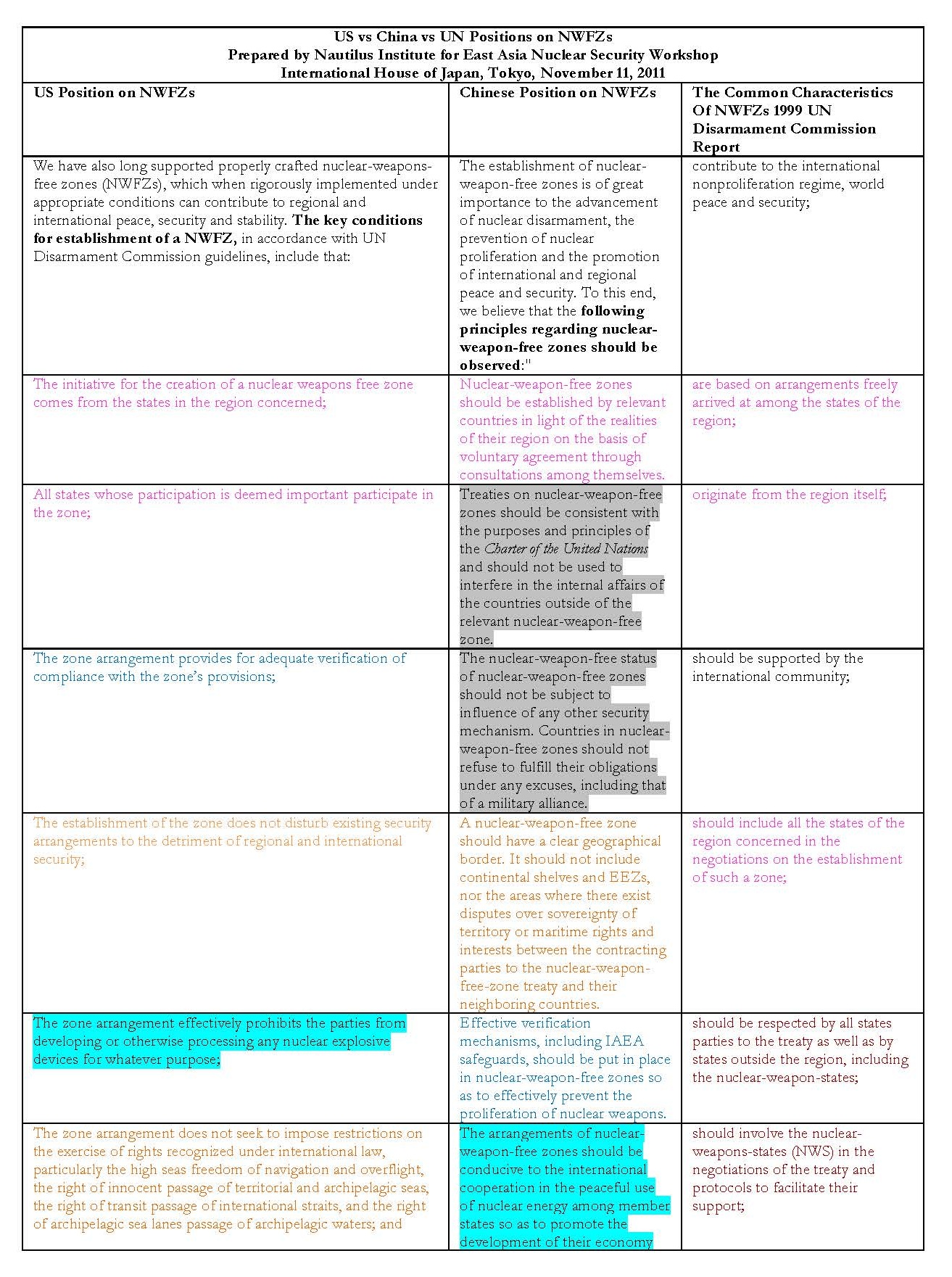

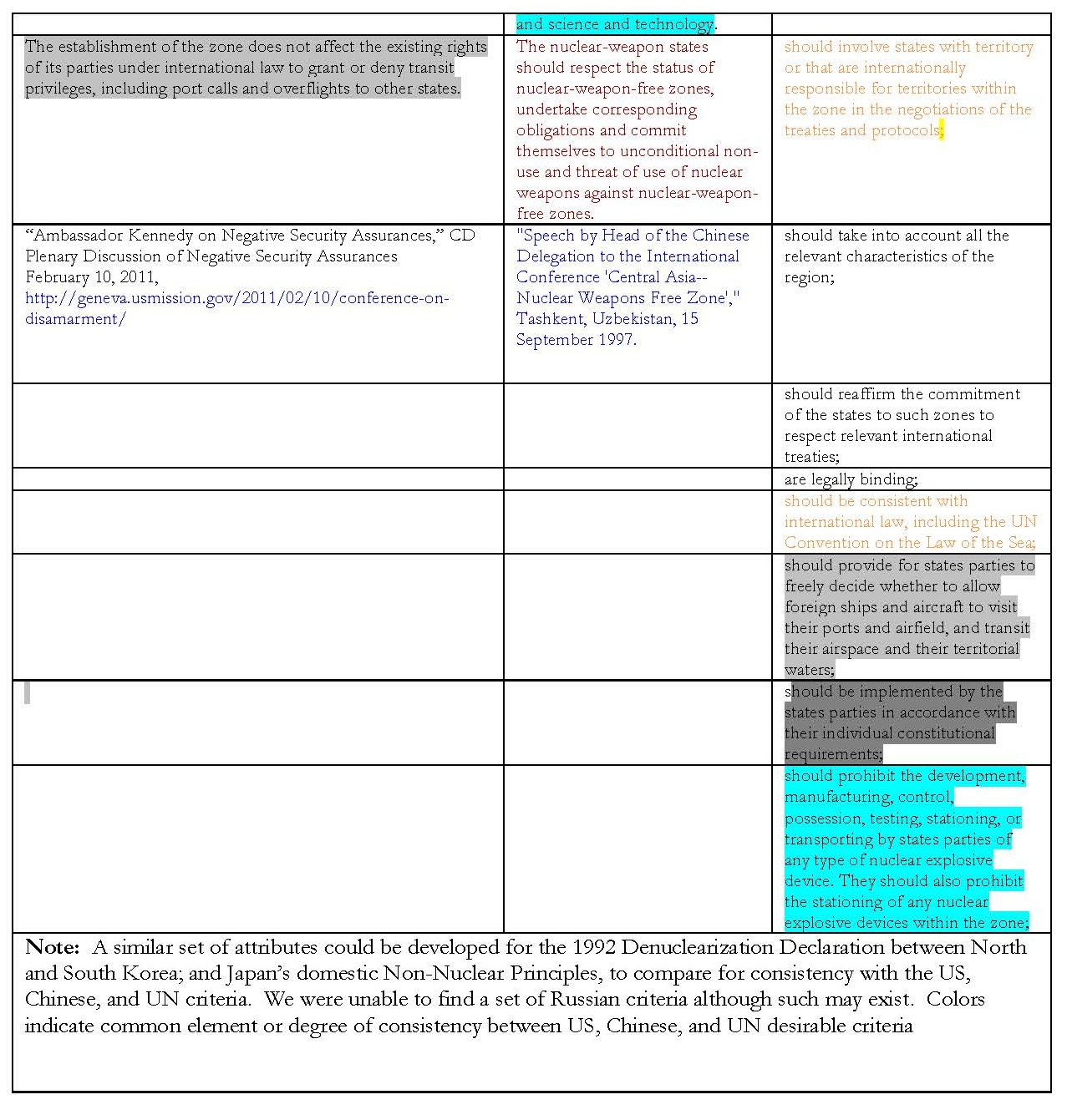

9. Acceptability to NWSs: US, Chinese, and UN criteria for an acceptable NWFZ reveal divergent concerns that must be addressed in a NEA NWFZ and bears careful reading (Attachment 3).

10. Critical Issues:

a) Are NWSs ready to forego the use of nuclear weapons and nuclear threat against NNWSs in the region, relegating nuclear weapons to strategic existential deterrence in regulating their relationships with each other in this region and with respect to the NNWSs party to the treaty, and reinstate such threats only after egregious violation of the treaty, that is, in response to the threat of or actual nuclear use by or against a NNWS party to the treaty?

b) Should NWSs impose a geographic restriction on deployment of nuclear-armed ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles in a verifiable zone as part of the NWFZ—in effect, the price charged by the US and Russia to China for delivering Japan, the ROK, and de facto, Taiwan, into a NWFZ?

c) Is a NEA NWFZ consistent with continuing nuclear extended deterrence, either explicit as in the US-ROK and US-Japan alliance relationships, or implicit, as in the US-Taiwan relationships, and the PRC-DPRK alliance? [12]

d) Should nuclear fuel cycle cooperation be included as part of the NWFZ treaty or as a separate set of parallel side agreements (some regional in scope, some likely DPRK-specific)?

e) Similarly, would a parallel agreement on regional space launch cooperation program under the regional security settlement treaty facilitate Japanese, ROK and DPRK commitment to a NEA-NWFZ?

f) Are conventional military means sufficient for the great powers and their allies to deter, compel, or reassure states that are party to a NEA-NWFZ and fulfill their mutual security obligations without recourse to nuclear threat or nuclear weapons? Are side agreements needed to restrain arms racing with offensive conventional weapons that undermine strategic stability and even restore the threat of mass destruction, only this time, by non-weapons?

g) Would a NEA-NWFZ commit NWSs to not fire nuclear weapons out of a zone, not just to not station them in the Zone or to transit them through via innocent passage? What provisions for emergency re-deployment, as apparently exist in the case of Japan and were implied in the 1991 withdrawal, would be allowed? (Otherwise, wittingly or unwittingly, a NNWS can become party to nuclear threat or nuclear use, transgressing its non-nuclear status to other parties of the treaty).

h) Are states, especially the US and China, ready to propose a NWFZ treaty as a stand-alone arrangement; or does it need a prior broad security settlement as proposed by Halperin? December 2012-June 2013 is a unique period in which leadership transitions in all six NEA states overlap. This opportunity for policy alignment may never recur. Should a track 1.5 Eminent Persons Group be convened to study a NEA-NWFZ and report to governments, and if so, when?

i) Would the DPRK find a NEA-NWFZ to be attractive, provided other DPRK conditions for denuclearization were met such as development assistance, etc?

[1] United Nations, “Establishment of nuclear-weapon-free zones on the basis of arrangements freely arrived at among the States of the region concerned,” Annex 1, Report of the Disarmament Commission, General Assembly, 54th session, Supplement No. 42 (A/54/42), United Nations, New York, 1999, p. 7, at: http://daccess-ddsny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N99/132/20/PDF/N9913220.pdf?OpenElement

[2] Possibly involving states already allied with UNC under a new UNSC mandate. The 16 UNC member countries are Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, France, Greece, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Philippines, South Africa (rejoined in 2010), Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom, and the United States. “The UNC continues to maintain a rear headquarters in Japan. Unique to that presence is a status of forces agreement that allows the UNC Commander to use seven UNC-flagged bases in Japan for the transit of UNC aircraft, vessels, equipment, and forces upon notification to the government of Japan. During 2010, four naval vessels and four aircraft called on ports in Japan under the auspices of the UNC. Almost 1,000 military personnel participated in these visits. The multi-national nature of the UNC rear headquarters is reflected in its leadership. Last year for the first time, a senior officer from Australia assumed command of the headquarters, while the deputy is an officer from Turkey.” In “Statement Of General Walter L. Sharp, Commander, United Nations Command; Commander, United States-Republic Of Korea Combined Forces Command; And Commander, United States Forces Korea Before The Senate Armed Services Committee,” April 12, 2011, at: http://www.Armed-Services.Senate.Gov/Statemnt/2011/04%20april/Sharp%2004-12-11.pdf

[3] “Pivotal deterrence: This concept captures the possibility for nuclear weapons states to arbitrate between two adversarial states, and to deter them from attacking each other. This pivotal role does not imply impartiality, but it further complicates an already complex strategic situation and may supplant or be superimposed on old forms of strategic deterrence. Relevant contexts for the USA may be the Korean Peninsula, China–Japan relations, and Taiwan-China relations.” P. Hayes, R. Tanter, “Beyond the Nuclear Umbrella: Re-thinking the Theory and Practice of Nuclear Extended Deterrence in East Asia and the Pacific,” Pacific Focus, 26:1, April 2011, pp. 8-9 at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pafo.2011.26.issue-1/issuetoc

The concept was first explicated fully in Timothy W. Crawford, Pivotal Deterrence, New York: Cornell University Press, 2003.

[4] As argued by Shinichi Ogawa, “Link Japanese and Koreans in a Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone,” New York Times, August 29, 1997 at: http://www.nytimes.com/1997/08/29/opinion/29iht-edskin.t.html

[5] The exact mix of these prohibitions varies across zones. Recent zones prohibit more activities. Two issues are important in the NEA context. The first is stationing of nuclear weapons. Secret US-Japan agreements provided for US storage and/or re-introduction of nuclear weapons. President George Bush’s 1991 statement that “under normal circumstances, our ships will not carry tactical nuclear weapons,” and that land and sea-based warheads not withdrawn, dismantled and destroyed “will be secured in central areas where they would be available if necessary in a future crisis” also left open the possibility that the US might, presumably subject to consultation with allies, redeploy such weapons into Japan and the ROK. At the time, then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Colin Powell said that only 24 hours would be needed to reverse the order. Note: since 1991, many of the tactical and theater nuclear weapons in the US arsenal no longer exist. The only salient non-strategic weapon today is the now old B-61 thermonuclear warhead that is stored in the US and forward-deployed in some NATO countries. Practically speaking, re-deployment and forward stationing of nuclear weapons would be very difficult to achieve. Home-porting strategic nuclear submarines in allied ports is physically possible, but politically difficult, and would affect greatly a US second strike capability by increasing the vulnerability of these submarines to first strike.

The second important issue is transit. To avoid conflict between Japan’s domestic non-nuclear principles and transit of its narrow straits leading from the Sea of Japan/East Sea of Korea to the Pacific Ocean by US and then-Soviet warships, Japan limited its coastal jurisdiction in these straits to three nautical miles, allowing free international passage through a narrow strip of international waters. Leaving aside apparently commonplace past transit of US nuclear weapons transit via airfields and ports, not just innocent passage in the territorial waters of Japan, the adoption of a zone-wide 12 mile nautical limit for a NEA-NWFZ would change current Japanese legal treatment of the straits and the related legal regime under which transit could occur. President Bush’s statement is “BUSH’S ARMS PLAN; Remarks by President Bush on Reducing U.S. and Soviet Nuclear Weapons,” New York Times, September 28, 1991, at: http://www.nytimes.com/1991/09/28/us/bush-s-arms-plan-remarks-president-bush-reducing-us-soviet-nuclear-weapons.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm Powell is cited in Eric Schmitt, “Bush’s Arm Plan; Cheney Orders Bombers Off Alert, Starting Sharp Nuclear Pullback,” New York Times, September 29, 1991, at: http://www.nytimes.com/1991/09/29/world/bush-s-arm-plan-cheney-orders-bombers-off-alert-starting-sharp-nuclear-pullback.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

On Japan’s transit policy and territorial waters, see Chi-Young Pak, The Korean Straits, Martinis Nijhoff, 1988, pp. 79-81; on recent Chinese naval surface and submarine transit of the straits and Japanese response, see Peter Dutton, Scouting, Signaling, and Gatekeeping, Chinese Naval Operations in Japanese Waters and the International Law Implications, China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, at: www.usnwc.edu/cnws/cmsi/default.aspx

[6] Article 2 of the Protocol of the Southeast NWFZ specifies that: “Each State Party undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against any State Party to the Treaty. It further undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons within the Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone.” To date, the NWSs have resisted this provision, partly because the SEA-NWFZ covers the Exclusive Economic Zone, but also because it implies restrictions on the use of nuclear weapons from within the zone against adjacent zones. Eventually, the mosaic of such stringent zones could reinforce each other to prohibit all threat and all use of nuclear weapons, as envisioned by S.W. Cheon as a “Pan-Pacific nuclear weapon free zone (PPNWFZ), encompassing East Asia, South Pacific and Latin America.” In S.W. Cheon, “The Limited Nuclear Weapon Free Zone in Northeast Asia: Is It Feasible?” The Mongolian Journal of International Affairs, 14, 2007, p. 115, at: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=the%20limited%20nuclear%20weapon%20free%20zone%20in%20northeast%20asia%3A%20is%20it%20feasible&source=web&cd=10&ved=0CGIQFjAJ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sfu.ca%2Fmongoliajol%2Findex.php%2FMJIA%2Farticle%2Fdownload%2F31%2F31&ei=FrRoUM_1CeaZiAKPmIHYAg&usg=AFQjCNF3AKPQtXpEK97pNQshHqF6o9JA7w

[7] Endicott’s 15 year series of workshops first proposed a 1,000 km range from the Korean DMZ that covered parts of Alaska, China, Mongolia, and Russia as well as Korea and Japan; and later, an ellipse that covered NE China, Mongolia, the Russian Far East, part of Alaska, the two Koreas, Japan, and Taiwan at the southern end. See J. Endicott, “Limited nuclear-weapon-free zones: the time has come,” Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 20: 1, 2008, p. 17, at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10163270802006305.

Endicott’s concept was reviewed critically by S. W. Cheon, op cit, pp. 106-115.

The 3+3 concept is advanced by H. Umebayashi, “A Northeast Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone with a Three Plus Three Arrangement,” East Asia Nuclear Security Workshop, Tokyo, Japan, November 2011, at: http://nautilus.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/UMEBAYASHI—A-NEA-NWFZ-with-3-3-Arrangement-_2011–Tokyo_.pdf; and similarly, Kumao Kaneko, “Japan needs no umbrella,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March/April 1996, pp. 46-51, at: http://www.thebulletin.org/

The first proposal phased implementation of a 3+3 concept is found in S. W. Cheon and T. Suzuki, “The Tripartite Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Northeast Asia: a Long-Term Objective of the Six Party Talks,” International Journal of Korean Studies, 12, 2, 2003, pp. 41-68, at: http://www.kinu.or.kr/eng/pub/pub_03_01.jsp?page=2&num=42&mode=view&field=&text=&order=&dir=&bid=DATA03&ses=&category=11

Nautilus’ 3+2 concept was advanced in: Korea-Japan Nuclear Weapon Free Zone (KJNWFZ) Briefing Paper, May 6, 2010, in English, Korean, and Japanese, at: https://nautilus.org/projects/by-name/korea-japan-nwfz/

[8] There is extensive precedent in the case of South Africa, Iraq, and Libya for documenting such dismantlement. See D. Albright, C. Hinderstein, Cooperative Verified Dismantlement of Nuclear Programs: An Eye Toward North Korea, June 1, 2003, at: http://isis-online.org/conferences/detail/cooperative-verified-dismantlement-of-nuclear-programs-an-eye-toward-north-/10 and Andre Buys, Proliferation Risk Assessment of Former Nuclear Explosives/Weapons Program Personnel: South African Case Study, NASPNet Special Report, July 14, 2011, at: www.nautilus.org/publications/essays/napsnet/reports/Buys-research-report-final.pdf and A. Buys, Tracking nuclear capable individuals, NAPSNet Special Report, Nautilus Institute, April 19, 2011, at: http://nautilus.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Tracking_Nuclear_Individuals_Buys.pdf

[9] The phrase ‘nuclear aggression’ is used deliberately, and refers to UNSC Resolution 255 on 19 June 1968 which “Recognizes that aggression with nuclear weapons or the threat of such aggression against a non-nuclear-weapon State would create a situation in which the Security Council, and above all its nuclear-weapon State permanent members, would have to act immediately in accordance with their obligations under the United Nations Charter,.”

This commitment was reaffirmed and strengthened by in UNSC Resolution 984 on April 11, 1995 which states that NWS members of the UNSC will also investigate and take measures to restore the situation, offer the victim technical, medical, scientific or humanitarian assistance, and to recommend compensation under international law from the aggressor for loss, damage or injury sustained as a result of the aggression. See Programme for Promoting Nuclear Non-Proliferation, Treaties, Agreements and other relevant documents, volume II, 8th edition, 2000, chapter 6, “Security Assurances,” at: http://www.ppnn.soton.ac.uk/bb2table.htm

Since 2009, North Korea’s nuclear threats arguably fall into the category of such aggression, as is argued in P. Hayes, S. Bruce, “North Korean Nuclear Nationalism and the Threat of Nuclear War in Korea,” NAPSNet Special Report, April 21, 2011 at: https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/11-09-hayes-bruce/ and “Supporting Online Material: North Korean Nuclear Statements (2002-2010)”, May 17, 2011, at: https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/supporting-online-material-north-korean-nuclear-statements-2002-2010/

However, any nuclear threat, whether clinical or flamboyant, may be perceived as aggressive, especially (as was the case in the last US Nuclear Posture Review) where specific countries are named. It likely would be counterproductive to refer to nuclear aggression in a NEA-NWFZ, and no other NWFZ treaty text has done so. Personal communication, Amb. Thomas Graham to Peter Hayes, September 30, 2012.

[10] This approach is transposed from the Tlatelolco Treaty which established an ingenious and innovative legal mechanism by which reluctant states could be encouraged to join the zone at a later date. It consists of a provision in Article 28 (3) that allows a signatory state to “waive, wholly or in part” the requirements that have the effect of bringing the treaty into force for that state at a particular time.11 As Mexican diplomat Alfonso Garcia Robles noted in his commentary on Article 28: “An eclectic system was adopted, which, while respecting the viewpoints of all signatory States, prevented nonetheless any particular State from precluding the enactment of the treaty for those which would voluntarily wish to accept the statute of military denuclearization defined therein. The Treaty of Tlatelolco has thus contributed effectively to dispel the myth that for the establishment of a nuclear-weapon-free-zone it would be an essential requirement that all States of the region concerned should become, from the very outset, parties to the treaty establishing the zone. In this way, the normative framework for a non-nuclear region can be established before all states are ready to actually implement the framework.” M. Hamel-Green, “Implementing a Korea–Japan Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone: Precedents, Legal Forms, Governance, Scope, Domain, Verification, Compliance and Regional Benefits,” Pacific Focus, 26:1, April, 2011, pp. 97-98, at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pafo.2011.26.issue-1/issuetoc

[11] “As of late 2011, 138 out of 193 UN member states have entered into, and ratified, legally binding treaties to reduce or constrain nuclear weapon proliferation, development and basing in their own regions (or other regions over which they have territorial claims)1. These include the 1959 Antarctic Treaty (47 states with interests in Antarctica), the 1967 Tlatelolco Treaty (33 Latin American states), the 1985 Rarotonga Treaty (13 South Pacific States), the 1995 Bangkok Treaty (10 Southeast Asian states), the 1996 Pelindaba Treaty (30 African states, with a further 21 signed but not yet ratified), and the 2006 Semipalatinsk Treaty (5 Central Asian States). NWFZs now cover almost the entire Southern Hemisphere, and wide swathes of the Northern Hemisphere, including the most recent Central Asian zone, which is entirely in the Northern Hemisphere.” Hamel-Green, M., Regions That Say No: Precedents and Precursors for Denuclearizing Northeast Asia, East Asia Nuclear Security Workshop, Tokyo, Japan (November 2011) at: http://nautilus.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Hamel-Green—TOKYONEANWFZPAPERvs5.pdf

Other treaties also denuclearize geographic areas, viz: the Outer Space Treaty, the Moon Agreement, and the Seabed Treaty. Mongolia’s 1992 self-declared nuclear-weapon-free status has been recognized internationally through the adoption by consensus of UN General Assembly Resolution 53/77D in December 1998 on “Mongolia’s international security and nuclear weapon free status.”

Arguably, the Korean Joint Denuclearization Declaration (1992) also established a limited NWFZ in Korea, now moribund.

Thousands of cities and provinces have established local NWFZs, and some states (New Zealand) have written their non-nuclear status into their legal system or (The Philippines) into their constitution. However, these are not treaty-based zones nor recognized by the UN under international treaty law. The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, not yet in force, will ban nuclear explosions, and prohibit and prevent any such nuclear explosion at any place under a state party’s jurisdiction or control.

[12] Actual arrangements between NWSs and NNWSs vary on this score from zone to zone. Dhanapala argues that they cannot do so in J. Dhanapala, “NWFZS and Extended Nuclear Deterrence: Squaring the Circle?” NAPSNet Special Report, May 1, 2012, at: https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/nwfzs-and-extended-nuclear-deterrence-squaring-the-circle/ The experts cited in the 1975 UN study of NWFZs split on whether nuclear deterrence could be extended to NNWSs party to a NWFZ. See Comprehensive Study Of The Question Of Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones In All Its Aspects, Special report of the Conference of the Committee on Disarmement , UN Doc. A/10027/Add. 1, New York, 1975 http://www.un.org/disarmament/HomePage/ODAPublications/DisarmamentStudySeries/PDF/A-10027-Add1.pdf

V. Nautilus invites your responses

The Nautilus Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please leave a comment below or send your response to: napsnet@nautilus.org. Comments will only be posted if they include the author’s name and affiliation.