by Mark Valencia

7 May 2013

I. Introduction

In this Policy Forum Mark Valenica sets out the kind of statement China could issue in order to ‘clarify its position regarding its maritime claims and actions in the South China Sea.’ Valenica writes ‘For China such a statement would indicate it has “risen” and is ready to challenge the existing world system and contemporary interpretations of international law—if necessary to protect its interests.’

Mark J. Valencia is a Visiting Senior Scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Policy Forum by Mark Valencia

The South China Sea: What China Could Say

China’s claims in the South China Sea have been criticized as ambiguous. China has also been accused of having claims that are inconsistent with international law and the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea which it has ratified. More specifically China has been accused of threatening freedom of navigation and “stretching” international law. The United States and several ASEAN nations have repeatedly asked China to clarify its position regarding its maritime claims and actions in the South China Sea. China could oblige them by issuing a statement along the following lines.

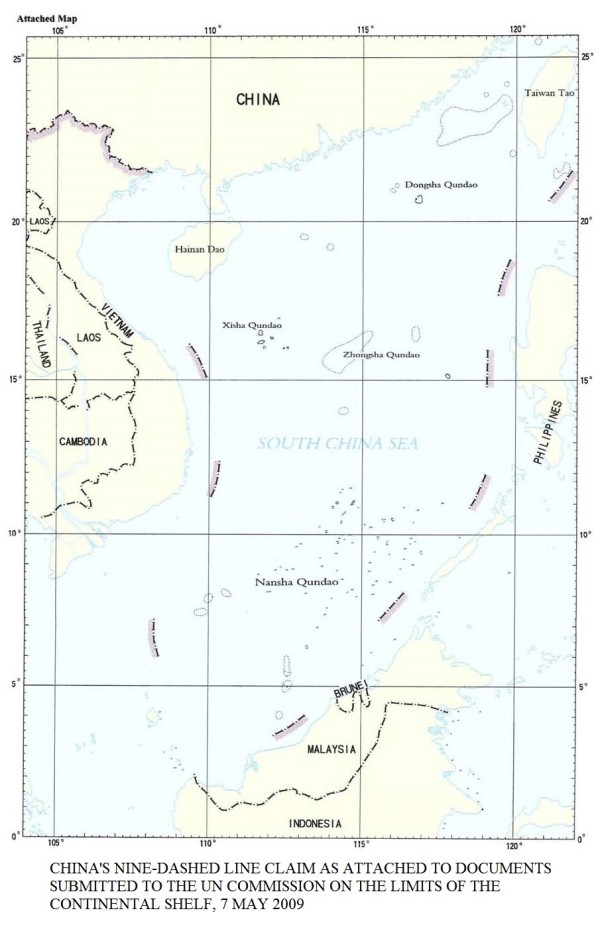

*As stated in its Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf, China claims historic rights in much of the South China Sea. This claim is symbolized by its nine-dashed line map. This claim includes sovereignty over all the islands, rocks, reefs and banks within this nine-dashed line. It also includes sovereign rights over the living and non-living resources as well as the quality of the marine environment. The extent of its claim, the sharing of resources within it, and the details of the regime itself are subject to negotiation.

*The 1982 UNCLOS does not define historic title, historic rights or historic waters. China’s claim of historic rights is distinct from the concept of historic waters in that the latter is commonly considered to imply a regime of internal waters that does not permit freedom of navigation and over flight. China has not and will not impede the freedom of navigation for commercial and normal peaceful purposes.

*China also reserves its rights under the 1982 UNCLOS to claim territorial waters, continental shelf, extended continental shelf, and EEZs from its sovereign territory within the nine-dashed line.

*Since maritime boundaries within the nine-dashed line area have not been agreed and the area is in dispute, there should be no unilateral drilling for hydrocarbons. The claimants should enter into interim arrangements of a practical nature such as joint development of resources in disputed areas.

*China has been consistent in its policy of being willing to negotiate these issues. China has proven its sincerity in negotiating and abiding by conflict management agreements in similar situations such as with Vietnam in the Beibuwan, with Japan in the East China Sea regarding oil and gas, fisheries and scientific research, and with the Republic of Korea in the Yellow Sea regarding fisheries. China has also offered to fund cooperative activities in the South China Sea without prejudice to any state’s claims to the area.

*China believes that the United States, despite its claims to the contrary, is not neutral in this matter. The U.S. insists that China must base its claims solely on the 1982 UNCLOS although the U.S. itself has not ratified it. The U.S. insists that any claims to maritime jurisdiction in the South China Sea must be from land implying that China’s claim to historic rights within the nine-dashed line is invalid. The U.S. also insists that China negotiate these issues multilaterally with a bloc of claimants and non-claimants. China believes that settlement of the disputes should be negotiated by ‘sovereign states directly concerned’ as stipulated in the 2002 ASEAN-China agreed Declaration of Conduct in the South China Sea (DoC) and that non-regional parties should not be involved. China also urges the ASEAN claimants to resolve relevant outstanding issues between themselves first.

*Regarding creation, evolution and interpretations of international law, it should be borne in mind that the U.S. itself unilaterally initiated the concept of “extended maritime jurisdiction” via the 1945 Truman Proclamation on the Continental Shelf. It justified doing so by “the long range world-wide need for new sources of petroleum and other minerals”; that “efforts to discover and make available new supplies of these resources should be encouraged”; and that “ recognized jurisdiction over these resources is required in the interest of their conservation and prudent utilization when and as development is undertaken.”

* China maintains that other claimants are violating the 2002 DoC by conducting ‘activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability’ such as occupying or building structures on disputed features, unilaterally exploring for petroleum, internationalizing the issues, conducting military exercises with outside powers, and violating China’s fisheries laws. China urges other claimants to abide by the DoC and refrain from such activities.

*China is hopeful that a mutually agreeable Code of Conduct (CoC) can be negotiated with ASEAN. However, the CoC should contain guidelines for peaceful cooperative behavior and a crisis management mechanism–not a dispute settlement mechanism.

*China looks forward to peaceful settlement of the disputes and cooperative use of the South China Sea.

Issuing an official statement along these lines would clarify China’s position without fundamentally sacrificing its claims or interests. More important it would bring the debate within the realm of international comity and parlance. Further, it should help mollify the naval powers regarding the ‘freedom of navigation’.

Of course the legal purists who think international law is absolute and unchanging and are wedded to the status quo –which favors Western powers—will criticize this position. But the reality is that ‘international law is the arms of geopolitics’ and its evolution and interpretation will be influenced by rising nations –just as they have been influenced by today’s ‘global leaders’. For China such a statement would indicate it has “risen” and is ready to challenge the existing world system and contemporary interpretations of international law—if necessary to protect its interests.

III. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSES

The Nautilus Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please leave a comment below or send your response to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Comments will only be posted if they include the author’s name and affiliation.

In his concluding statement Mr Valencia implies that conflicts in the South China Sea are somehow related to existing international laws favoring Western powers. Nothing can be further from the truth. The UNCLOS gained wide acceptance not because it favors Western powers, but because countries large and small all over the world, including all countries around the South China Sea, have subscribed to it, a major exception being the predominant western power, the USA. Non-western powers and smaller maritime countries in particular approved of the UNCLOS and associated international legal mechanisms because they give them protection against big powers, western and others.

The UNCLOS applies equally to all nations but is particularly useful to weaker nations. To modify laws that have been widely accepted by the international community to favor a particular power, as Valencia is advocating it for China, is to revert to a colonial system where the stronger countries grab what they can from the weaker by force or intimidation. Furthermore, notwithstanding the fact that China’s “historical rights” claim are tenuous and one-sided at best (Malay and Indonesians cruised the SCS and Indian ocean long before the Chinese ventured far from their shores), legitimizing these rights would open a Pandora’s box of conflicting historical claims all over the world, as perceived national boundaries have fluctuated and overlapped in the seas even more than on land.

Any peace loving person should try to pressure China to adhere to the UNCLOS rather than encouraging it to dismantle an international legal system which, for all its imperfections, have helped prevent or resolve peacefully many international disputes.

I agree with Mr. Valencia, and indeed the international law of the sea has become the extended arm of geopolitics, whether one likes it or not. In the declaration made upon its rectification of the UNCLOS in June 1996 China expressly reserved its claimed sovereignty right over, inter alia, the South China Sea. So “to pressure China to adhere to the UNCLOS”, as Mr Tuan Pham suggests, is merely to seek to force China to accept a set of rules which it expressly excluded and never agreed should be applied to the South China Sea. Whether this helps to maintain peace or encourage dispute is plain to see.

That “international law” is the arm of geopolitics is further proved by the development of events since 2013, when the US has since the end of 2014 mobilized its considerable resources to object to the reclamation of islands by China when several surrounding countries in the region have been doing that for decades. The justification of the US for doing that was also based on “international law”. But little did the US mention that it was not even a signatory of the UNCLOS. So the “international law” the US relied upon is the custom international law which was created by the colonial powers in their mutual favour. Why should a a sovereign nation adheres to such law created by a group of other nations in their own interest? And in the absence of a set of international law which China has expressly subscribed without reservation, there is no logical reason why China cannot propose a new concept of international law over the South China Sea dispute and to seek the agreement with other concerned parties.

International law is a living creature which must continue to evolve to accommodate new features and claims, with the ultimate aim of maintaining peace, instead of provoking dispute, among nations. The rise of China and its unique perspective on historical claims of waters has provided an opportunity, alternatively a challenge, for the concerned parties to review the law of the sea with a view to achieving a peaceful settlement which, though may not be satisfactory to all, at least be acceptable to all.

It never ceases to amaze me is how some “scholars” seem to have missed the most important educational lesson of all—that credible research is approached and accomplished with an open mind. Indeed the tone and tenor of Mr. Tuan Pham’s polemic proves my point that international law has become the arms of geopolitics. The author uses his interpretation of the law to further some nations’ interests at the expense of another, rather than search for a solution to the international conflict.

Apparently Mr. Tuan Pham either did not understand or read my article fully before firing off his polemic. I was referring to international law in general – both customary – as derived from state practice, and conventional law, not specifically UNCLOS. UNCLOS is not the only law applicable to claims in the South China Sea. General international law was developed mainly by Western colonial powers and favors their interests. Moreover the interpretation of UNCLOS is evolving and certain controversial provisions have many interpretations such as Vietnam’s interpretation of its baselines provisions.

There is no ‘reversion’ involved. The world system is what it is –powerful countries’ interests predominate. Neither Mr. Tuan Pham nor I can change that – – as much as he or I might wish to do so. It is true that legitimizing historical claims would open a Pandora’s jar – just as the U.S. did by its unilateral Truman Proclamation of 1945. International law evolves with state practice—this is not new nor “revolutionary”.

Finally, no ‘peace loving person’ should try to ‘pressure’ any country. I am not encouraging China to do anything – only stating a possible argument China might make. Perhaps Mr. Tuan Pham should suggest that Vietnam take the lead in bringing its state practice into conformity with UNCLOS starting with its baselines and its requirement for foreign warships to give prior notice before entering its territorial sea?

Mark J. Valencia

Mr Valencia keeps referring to Vietnam’s baseline and requirements about foreign warships in its territorial sea as a counterpoint to criticism of China’s claims. Let me assure him that I do not support these policies and would be happy to join any effort to persuade Vietnam to change them. However, the principal threat and the biggest claims by far in the South China Sea come from China not Vietnam, so let us not be diverted from the main subject matter.

As Mr Valencia rightly remarked, the interests of the powerful always predominate, but that is precisely why we need a legal system to protect the weak, and this is as true of the community of nations as of any other human society. If you want the world to evolve towards a more civilised and equitable system, you cannot encourage the bigger countries to ignore the law or twist it to suit themselves while disadvantaging their smaller neighbours. Yet this is what Mr Valencia appears to do in the concluding paragraphs of his article. It is also ironical for him to say that I used my “interpretation of the law” to further some nations’ interests at the expense of another (by which presumably Mr Valencia meant China), since China is the country which is demanding far more than its legitimate share of the cake, pushing its illegal claims deep into the EEZ of its smaller neighbours, and in some case skirting their territorial waters, thousands of kilometres from the Chinese mainland. Surely it is precisely a purpose of the law to protect the weak against bullies?

It is not true that historical rights (beyond territorial waters) have been ignored by the UNCLOS and that countries are therefore entitled to make new interpretations about them. Article 62 of the UNCLOS specifically refers to the duty of coastal states to “minimize economic dislocation in States whose nationals have habitually fished in the [exclusive economic] zone”. This appears to be a perfectly reasonable basis for the peaceful resolution of possibly overlapping historical fishing claims. (People of course did not exploit continental shelves in ancient history.)

I wonder what laws Mr Valencia was thinking of when he said that “UNCLOS is not the only law applicable to claims in the South China Sea. General international law was developed mainly by Western colonial powers and favors their interests.” Regarding China’s position regarding its maritime claims, the central topic that Mr Valencia’s article addresses, the salient bodies of international law are the UN’s Constitution, UNCLOS, jurisprudence on maritime delimitation, and the principle of “the land dominates the sea”, which states that claims to maritime space must be derived from land and insular territories. These were not “developed mainly by Western colonial powers and favor their interests”. They are not prejudiced against China vis a vis the other claimants.

The Truman declaration of 1945 can in no way be compared to China’s use of historical rights to make extensive maritime claims. The former extended a country’s economic area but did not infringe any other country’s existing maritime domain. Far from disadvantaging other countries (which countries were advanced and powerful enough to drill for riches on the doorstep of the USA?), it opened the way for all coastal countries to exploit resources they did not have access to previously, and to protect themselves from the richer maritime powers. On the other hand, China’s use of dubious historical rights to claims maritime areas thousands of miles from its coasts, often right on the doorstep of other countries, not only infringes on the legitimate rights of its maritime neighbours, but if accepted as a legal principle would create dangerous conflicts all over the world. As such it would definitely be a regressive step for the whole world. One must not forget that similar concepts of “historical rights” on land have been a major cause of two world wars and countless other conflicts that continue to this day.

I cannot agree with Mr Valencia that no peace loving person should try to pressure any country. The world will be a better place if countries (by that of course I mean governments) are under constant pressure from ordinary people to obey the law and live up to the principles of moral behaviour, whether it’s during France’s colonial wars, the USA’s war in Vietnam or the Western invasion of Iraq. Institutions such as slavery in the Americas and the apartheid system in South Africa would have continued for much longer were it not for the pressure applied on the oppressors.

In conclusion, the view that international laws are there to serve the interests of powerful countries (Western or Chinese), that the rights of the weaker countries are of little import, and that we should simply shrug our shoulders about it, is in my opinion a highly pessimistic and cynical, even immoral, attitude that will not do nothing to further world peace.

I agree with Mr. Valencia, and indeed the international law of the sea has become the extended arm of geopolitics, whether one likes it or not. In the declaration made upon its rectification of the UNCLOS in June 1996 China expressly reserved its claimed sovereignty right over, inter alia, the South China Sea. So “to pressure China to adhere to the UNCLOS”, as Mr Tuan Pham suggests, is merely to seek to force China to accept a set of rules which it expressly excluded and never agreed should be applied to the South China Sea. Whether this helps to maintain peace or encourage dispute is plain to see.

That “international law” is the arm of geopolitics is further proved by the development of events since 2013, when the US has since the end of 2014 mobilized its considerable resources to object to the reclamation of islands by China when several surrounding countries in the region have been doing that for decades. The justification of the US for doing that was also based on “international law”. But little did the US mention that it was not even a signatory of the UNCLOS. So the “international law” the US relied upon is the custom international law which was created by the colonial powers in their mutual favour. Why should a a sovereign nation adheres to such law created by a group of other nations in their own interest? And in the absence of a set of international law which China has expressly subscribed without reservation, there is no logical reason why China cannot propose a new concept of international law over the South China Sea dispute and to seek the agreement with other concerned parties.

International law is a living creature which must continue to evolve to accommodate new features and claims, with the ultimate aim of maintaining peace, instead of provoking dispute, among nations. The rise of China and its unique perspective on historical claims of waters has provided an opportunity, alternatively a challenge, for the concerned parties to review the law of the sea with a view to achieving a peaceful settlement which, though may not be satisfactory to all, at least be acceptable to all.