PETER HAYES

FEBRUARY 8, 2018

I. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, Peter Hayes describes US Force Korea’s “NONCOMBATANT EMERGENCY EVACUATION INSTRUCTIONS” issued in 1967, 1983, and 2010. He concludes that: “These documents provide a realistic sense of the demanding, time consuming, and complicated task of evacuating noncombatants from Korea, and suggest it would be difficult if not impossible to prepare for such an operation in secret.”

Peter Hayes is Director, Nautilus Institute and Professor, Center for International Security Studies, Sydney University.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

Banner Images: taken from the 1967 and 1983 pamphlets.

II. NAPSNET SPECIAL REPORT BY PETER HAYES

US FORCES KOREA: NONCOMBATANT EMERGENCY EVACUATION INSTRUCTIONS

FEBRUARY 8, 2018

Evacuation of non-combatant Americans and other nationals registered for evacuation in Korea covers a range of possible circumstances including natural disasters and military conflict. Commencement of evacuation is a possible indicator of American intention to use military force against North Korea. Even visits by the US official with oversight of noncombatant personnel are reported by the ROK media.[1] False social media and text messages to evacuate noncombatant US military dependents in the ROK in September 2017 were also viewed with concern due to potential perception by the DPRK that it might indicate that an attack is under way.[2] USFK regularly conducts exercises for noncombatant evacuation—for example, Courageous Channel in 2015.[3]

Of course, if US forces in Korea end up fighting in response to North Korean attack, evacuation of non-combatants will take place during and likely in the midst of fighting, at which point it is an important concern for US policymakers and for the ROK government, but not one that would serve early warning to North Korean analysts as to the possibility that an attack on the DPRK may be pending.

In this NAPSNet Special Report, we present three USFK advisory publications for non-combatant evacuation. These documents provide a realistic sense of the demanding, time consuming, and complicated task of evacuating noncombatants from Korea, and suggest it would be difficult if not impossible to prepare for such an operation in secret.

The first, published in 1967 by USFK as EA Pam 600-300 at the height of the first Cold War, gives details instructions for registration, alert systems, assembly, staying put, or moving, including maps. It explains the division of responsibility between the US State for the safety of US citizens outside the United States, and the Defense Departments which cooperates with the State Department to ensure the safety of noncombatants accompanying US military forces and assists the State Department, as the military situation permits, in relocating or evacuating noncombatants from areas of danger.

It includes reference to seeking shelter, and on staying put under conditions of nuclear attack, stating that after an All Clear message, noncombatants are to: “Await instructions for leaving the shelter. Since, in the event of a nuclear attack, large areas may still be subject to danger from radioactivity, release from shelters will be on a selective and local basis with priority given to personnel who must carry out emergency operations.”

Noncombatants are also instructed on what to do during “civil disturbances” conditions referred to as “PURPLE” and “PURPLE ONE” (South Korea was then a military dictatorship and many protests including street protests were brutally put down), restricted movement. It is available in PDF form here.

It starts by informing the noncombatant: “a) As a sponsored noncombatant or a non-combatant U.S. citizen in Korea, you have, at some time, required or may require the assistance of the military forces. In the event of an emergency, the military men who provide such services will be engaged in their primary duties. The amount of assistance they can give you will be considerably lessened. b) If there is a crisis, you must be prepared to take care of yourself or your family with a minimum of outside assistance.”

The second, published in 1983 by USFK as EA Pam 600-300 as the second Cold War began in earnest. The advice no longer refers to civil disturbances and contains much less detail about evacuation routes. It states that “The Commander, USFK, upon the request of the US Ambassador to Korea, controls the registration, reporting, briefing, collection, processing, and relocation or evacuation of noncombatants in emergencies.” It is available in PDF form here.

These two documents were provided to Nautilus Institute under a US Freedom of Act request.

The third, available in PDF form here and published on-line here in 2010 by USFK as USFK Pamphlet 600-300, provides a current description of who is covered:

“U.S. government affiliated noncombatants include immediate family members of military service members or civilians in the employment of a U.S. federal agency who are U.S. citizens (AMCIT), as well as those AMCIT civilians employed by the U.S. government in positions deemed non-essential during a crisis on the peninsula. The latter group also includes AMCIT invited contractors and technical representatives (and their immediate households) whose presence on the peninsula is in direct support to the U.S. military or other U.S. federal agency. Should a crisis warrant it, U.S. government affiliated noncombatants can be ordered to leave the peninsula by authorities in the federal government or their representatives here in Korea. Other noncombatants, such as those AMCITs in Korea for private business or personal pursuits, may be authorized assistance by the U.S. Embassy (AMEMB) in Seoul or U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) during a crisis. This USFK pamphlet provides important information on how noncombatants should prepare for and respond to a crisis on the Korean peninsula that would necessitate their rapid evacuation due to concern for their personal safety. This pamphlet outlines procedures used during noncombatant evacuation operations (NEO), gives guidance to potential noncombatant evacuees (NCE) on how they can prepare for such a contingency, and outlines the assistance noncombatants can expect from the U.S. government and military authorities.”

(note: NEO refers to Noncombatant Evacuation Operations)

It informs noncombatants that: “In a “worst case scenario,” an evacuation ordered due to the potential resumption of hostilities on the Korean Peninsula, the warning time prior to NEO may only be a matter of hours. Upon notification of such an event, it is time to move – not time to begin preparations. Preparations include both physical and mental aspects.”

It explains who is responsible as follows: “The AMEMB in Seoul has the overall responsibility to safeguard and protect AMCITs and their family members in Korea. USFK will execute military operations in support of the AMEMB during a NEO. NEO in Korea has one primary objective: to remove American citizens and their immediate families from danger quickly and safely. The NEO system relies heavily upon the U.S. military to provide forces, facilities, and equipment necessary to execute the NEO plan. There are five separate and distinct steps in the NEO concept: alert, assembly, relocation, evacuation, and repatriation.”

Noncombatants may have to pay their own way: “If your movement to Korea was not paid for by the U.S. government (i.e. you are non-Command sponsored), you may be asked to sign a promissory note to repay the cost of your transportation and life support assistance. Charges will not be collected prior to evacuation so command sponsorship status does not affect your evacuation priority.”

And for non-US citizens who are non-combatant family members, they may not be accepted immediately into the United States for safe haven, presenting an exquisite dilemma for those with some eligible and some possible ineligible family members: “Those noncombatant evacuees who are not American citizens or Legal Permanent Residents of the U.S. (green card holders), can expect a delay in a safe haven while U.S. immigration officials process their cases. While a liberal parole visa policy will likely be in effect for NCEs leaving Korea, granting such visas is not an instantaneous or automatic process.”

Some of the true complicating circumstances that will come into play during a noncombatant evacuation are spelled out in sections 2-7, 8 and 9.

“2-7. Armed Conflict

- Gradual Escalation. If the threat of armed conflict increases gradually, you may decide to leave Korea voluntarily, at your own expense. If departure is recommended by the U.S. government, it may be at the U.S. government’s expense, depending upon the noncombatants’ status. (1) During the early stages of a crisis, such recommendations will likely be made by AMEMB or military officials. In these situations, the military will facilitate the orderly departure of U.S. military affiliated noncombatants to the maximum extent possible. (2) U.S. military affiliated noncombatants must understand that, depending upon their sponsorship status, some or all of the cost of their departure may be recouped by the U.S. Government. They must also understand that it is unlikely that the U.S. government will reimburse them for their return to Korea if the crisis is resolved following their departure.

- Sudden Crisis. If a crisis occurs rapidly, and normally available commercial means of travel are no longer available, U.S. government authorities may declare and execute NEO. (1) Noncombatants should remain indoors at home and monitor AFN-K radio or TV. USFK will transmit as much and as early as possible information and instructions to noncombatants through AFN-K and other media. (2) AFN-K and your NEO warden will instruct you when and where to report in case of a NEO. Be prepared to move quickly and cooperate completely with military forces upon arrival.

2-8. Children In School (Received from DODDS Safety/Security Manager) Although every effort will be made to maintain U.S. military affiliated family integrity during the NEO process, there may be certain situations which require the immediate evacuation and will make this extremely difficult.

- If conditions do not permit returning students to parents, children will be relocated/evacuated by military authorities.

- The schools will release the students to a parent, guardian, or family member until it is obvious that no one is coming to pick the student up. At that time, the school will release the student into the custody of the military authorities. They in turn will supervise the relocation and evacuation of the student and try to re-unite the child with his parents as soon as possible.

2-9. Medical Cases Hospital patients who can safely travel without continuous medical supervision will be discharged and directed to report to the nearest assembly point or ECC. Noncombatants will be screened at each ECC to determine whether they should be evacuated through NEO or medical evacuation channels. If medical evacuation is deemed appropriate, every effort will be made to maintain family unit integrity during the evacuation process. 7 USFK PAM 600-300, 24 June 2010 a. Noncombatants with chronic medical conditions requiring regular prescription medication are advised to request a “contingency prescription” from their primary care provider, in addition to their regular prescription. b. Military pharmacies will fill a 30-day contingency prescription for inclusion in a noncombatant’s NEO bag, but it is the responsibility of the noncombatant to ensure that it is continually rotated with regular prescription refills in order to ensure a fresh supply in the event of an evacuation. There will be some exceptions to the 30-day policy depending on the type of medication.”

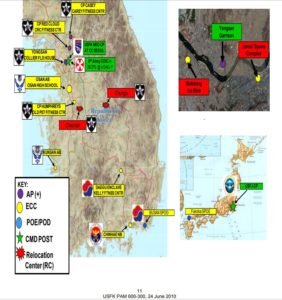

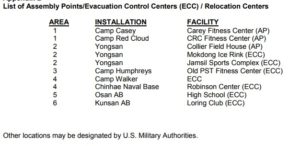

The 2010 pamphlet provides a map of Assembly Points/Evacuation Control Centers (ECC) / Relocation Centers shown below.

These are listed as follows:

In reality, in the course of a short notice war, many American citizens may take shelter in ROK designated shelters in the major cities. In 2010, the ROK issued the EMERGENCY READY APP which provides maps and locations using smart phone geolocation relative to the whereabouts of a viewer.[4]

III. ENDNOTES

[1] Lee Yong-soo, “Top U.S. Official in Charge of Evacuations Visited S.Korea,” Chosun Ilbo, September 20, 2017, at: http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2017/09/20/2017092001430.html

[2] D. Lamothe, “U.S. families got fake orders to leave South Korea. Now counterintelligence is involved,” Washington Post, September 22, 2017.

[3] USFK, “Courageous Channel exercise begins,” press release, October 2, 2015, at: http://www.usfk.mil/Media/Press-Releases/Article/621949/courageous-channel-exercise-begins/ The 2010 PAM 600-300 explains that: “An annual NEO readiness exercise designed to practice local NEO procedures. These exercises not only rehearse military forces in their NEO tactics, techniques, and procedures, but also inform and prepare noncombatants for a potential NEO.”

[4] The App is downloadable from ITunes and Play Store for Android, but only works to locate shelters if you are in the ROK using the GPS so it can give directions to the user’s nearest shelters—often public building basements or subway stations. See Canadian Embassy description of the EMERGENCY READY APP at: https://www.facebook.com/CanadainKorea/photos/a.691197707627429.1073741827.681967661883767/1701319396615250/?type=3&theater

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent

Good morning,

I am interested in obtaining the alerts released for all protests of USFK/US Military by Korean nationals from 2010-2019 for a research project. Please let me know if this is available for release, and if not – where I may be able to find other records of these demonstrations.

Thank you,

Hannah A. Cole