By Jennifer M. Gibson and Sarah Shirazyan

February 14, 2012

This is a report from the Nautilus Institute workshop “Cooperation to Control Non-State Nuclear Proliferation: Extra-Territorial Jurisdiction and UN Resolutions 1540 and 1373” held on April 4th and 5th in Washington DC with the Stanley Foundation and theCarnegie Endowment for International Peace. This workshop explored the theoretical options and practical pathways to extend states’ control over non-state actor nuclear proliferation through the use of extra-territorial jurisdiction and international legal cooperation.

This is a report from the Nautilus Institute workshop “Cooperation to Control Non-State Nuclear Proliferation: Extra-Territorial Jurisdiction and UN Resolutions 1540 and 1373” held on April 4th and 5th in Washington DC with the Stanley Foundation and theCarnegie Endowment for International Peace. This workshop explored the theoretical options and practical pathways to extend states’ control over non-state actor nuclear proliferation through the use of extra-territorial jurisdiction and international legal cooperation.

Other papers and presentations from the workshop are available here.

Nautilus invites your contributions to this forum, including any responses to this report.

——————–

CONTENTS

II. Report by Jennifer M. Gibson and Sarah Shirazyan

IV. Nautilus invites your responses

Jennifer M. Gibson, J.D. Candidate, and Sarah Shirazyan, J.S.D. Candidate, Stanford Law School, state that “Resolution 1540 has the potential to play an important role in forming universally recognized norms of state behavior with respect to WMDs. To do so, however, states must enact and enforce domestic controls over WMD material, wherever and whenever possible.” The authors. The following study assess the extent to which states have applied their domestic WMD controls extraterritorially by examining national reports and matrices submitted to the 1540 Committee to answer three questions. First, how many and which states apply their laws extraterritorially? Second, of those that do apply their laws extraterritorially, what is the scope of that application, i.e. does it apply to nuclear, biological and/or chemical materials? And, finally, what is the jurisdictional basis for the extraterritorial application?

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Report by Jennifer M. Gibson and Sarah Shirazyan

-“The UN Security Council Resolution 1540: An Overview of Extraterritorial Controls Over Non-State WMD Proliferation”

by Jennifer M. Gibson and Sarah Shirazyan

I. INTRODUCTORY NOTE

The proliferation of biological, chemical and nuclear weapons (also known as weapons of mass destruction (WMD [1])) is widely accepted as one of the greatest threats to international peace and collective security. [2]Despite numerous international and domestic efforts to prevent WMD proliferation, states and non-state actors [3] continue to see to develop and acquire the materials and means of delivering such weaponry. The events of 9/11 and subsequent revelations of clandestine networks, such as that of Pakistani Scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan, have highlighted the unprecedented threat terrorist networks pose to both peace and stability and the containment of WMDs. Terrorists “seek to cause mass casualties of unprecedented dangers,” making the need to defend against terrorist use of WMD materials a key concern for global security. [4] As the U.S. noted in its National Security Strategy shortly after 9/11, “the greatest threat our nation faces lies at the crossroads of radicalism and technology.” [5]

In order to respond to the multiple roles non-state actors play in WMD proliferation—as both recipients as well as suppliers—in 2004 the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1540 [6] on Non-Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction. [7] Generally speaking, Resolution 1540 imposed a range of binding obligations on all UN Member States to keep their biological, chemical and nuclear weapons and the means of delivering such weapons out of the hands of non-state actors. More specifically, it requires all Member States to adopt domestic controls and enforcement mechanisms over WMD materials and to criminalize possession of such materials, irrespective of where the actor is located. The resolution explicitly notes that all Member States shall:

- “refrain from providing any form of support to non-state actors that attempt to develop, acquire, manufacture, possess, transport, transfer or use nuclear, chemical or biological weapons and their means of delivery” (paragraph 1);

- “in accordance with their national procedures … adopt and enforce appropriate effective laws, which prohibit any non-state actor to manufacture, acquire, possess, transport, transfer or use nuclear, chemical or biological weapons and their means of delivery, in particular for terrorist purposes, as well as attempts to engage in any of the forgoing activities, participate in them as an accomplice, assist or finance them” (paragraph 2);

- “take and enforce effective measures to establish domestic controls to prevent the proliferation of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons and their means of delivery, including by establishing controls over related materials” by developing security, physical protection and border and export controls (paragraph 3). [8]

In order to monitor the progress of Member States in enacting effective domestic legislative and regulatory controls, Resolution 1540 established an ad hoc Committee (1540 Committee) to monitor state compliance.[9] Members States are required to report to the Committee on their progress, and recently, these reports have been transferred into matrices designed by the 1540 Committee. The matrices enable the Committee to break down the reports into identifiable indicators, thus allowing the Committee to more clearly track a country’s progress and identify gaps in a state’s compliance. [10]

Resolution 1540 has the potential to play an important role in forming universally recognized norms of state behavior with respect to WMDs. To do so, however, states must enact and enforce domestic controls over WMD material, wherever and whenever possible. The Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability commissioned this study to examine the extent to which states have applied their domestic WMD controls extraterritorially. The study examined national reports and matrices submitted to the 1540 Committee to answer three questions. First, how many and which states apply their laws extraterritorially? [11] Second, of those that do apply their laws extraterritorially, what is the scope of that application, i.e. does it apply to nuclear, biological and/or chemical materials? And, finally, what is the jurisdictional basis for the extraterritorial application?

II. EXTRATERRITORIAL JURISDICTION

Before detailing the principles upon which a state may assert its jurisdiction extraterritorially, it is worth noting that international scholars, in particular the American ones, think of three categories of jurisdiction:

- Jurisdiction to prescribe (prescriptive/legislative jurisdiction);

- Jurisdiction to adjudicate (adjudicative jurisdiction); and

- Jurisdiction to enforce (executive jurisdiction).

Prescriptive jurisdiction is the power of a state to regulate persons or activities. [12] More specifically, it is the power of the state to “make its law applicable to the activities, relations or status of persons or the interests of persons in things” as determined by legislation, administrative rule, executive action or judicial interpretation.[13] In contrast, judicial (adjudicative) jurisdiction is the power of a state agency (not necessarily a court) to adjudicate disputes. Generally speaking, executive jurisdiction relates to the power of one state to perform (execute) acts in the territory of another state.

The analysis and conclusions reflected in this paper focus solely on a state’s prescriptive jurisdiction to regulate activities related to WMD proliferation.

International law purports to regulate the capacity of states to exercise prescriptive jurisdiction, and enumerates a set of permissible bases upon which states may assert jurisdiction. Different commentators employ slightly different formulations to describe the different permissible bases of jurisdiction. It is, therefore, important to clarify the various bases of jurisdiction examined in this paper and how those terms are used.

International law generally recognizes five bases upon which a state can assert its national jurisdiction. Those five bases are often referred to as the Harvard Principles: [14]

- The principle of territoriality;

- The nationality principle (also known as active personality principle);

- The passive personality principle;

- The effects principle; and

- The principle of universal jurisdiction.

A. Territorial Jurisdiction

The most basic jurisdictional principle under customary international law is territorial jurisdiction, or jurisdiction that is based upon where a crime (or other regulated activity) occurred. [15] Commentators have distinguished between two types of territorial jurisdiction: objective and subjective. Subjective territorial jurisdiction recognizes jurisdiction of a state where the act has been committed, whereas objective territorial jurisdiction acknowledges the jurisdiction of a state where the act was completed or had an effect. For example, under the objective standard, a state may only have jurisdiction over the activities of a bomb-maker if he constructs a bomb that detonates in that country. In contrast, under the subjective standard, a state could have jurisdiction if any portion of the bomb-making occurred on its territory.

Territorial jurisdiction has its roots in the basic concept of state sovereignty. International law generally prohibits states from intervening in the domestic matters of another state, thus states generally possess exclusive power within their territorial boundaries. [16] The ability to exercise prescriptive jurisdiction is seen as an integral part of the state’s sovereignty and is often claimed to be an exclusive power belonging to states.

B. The Nationality Principle

Under international law, a second way states may exercise prescriptive jurisdiction is through the nationality or active personality principle. Under this principle, a state may regulate the conduct of its nationals, irrespective of where the national is located when the crime (or other regulated activity) is committed. While this principle primarily covers the state’s ability to apply its laws to its own citizens, the nationality principle also includes jurisdiction based on the domicile or residence of a suspect. Residence within that state or possession of a passport may serve as a solid basis for invoking national jurisdiction. The nationality principle is understood to be “universally conceded.” [17] Moreover, it is applicable not only to individuals, but also companies that have a seat or are registered in a particular country.

C. The Passive Personality Principle

Where the nationality principle permits a state to regulate the conduct of nationals, the passive personality principle extends jurisdiction when the victim of the crime is a national. [18] It permits a state to regulate conduct or activities that have injured one of its nationals. Under this principle a state might, for example, punish foreign nationals for crimes committed against its own citizens. Within the classic jurisdictional framework, passive personality jurisdiction has been observed to be “asserted in some form by a considerable number of states and contested by others” and is “admittedly auxiliary in character.” [19]

D. The Effects (Protection) Principle

The effects principle (also referred to as protective or security jurisdiction) enables a state to claim jurisdiction over activities that threaten its national security that have been committed outside of its territory, but that have a substantial effect within the territory or against a national interest. Normally, this basis allows a state to assert jurisdiction over offences directed against its security or vital interests, or offences threatening the integrity of governmental functions that are generally recognized as crimes. [20]

E. Universal Jurisdiction.

Universal jurisdiction allows a state to assert its jurisdiction over certain forms of conduct irrespective of where the conduct occurs or the nationality of the actor. Stated simply, universal jurisdiction allows a state to exercise jurisdiction “based solely on the nature of the crime.” [21] The important and controversial element of universal jurisdiction is that it is exercised by states with no nexus to the territory or nationality of the conduct or perpetrator in question. [22] In 2000 the International Law Association in its Final Report on the Exercise of Universal Jurisdiction in Report of Gross Human Rights Offences defined universal jurisdiction as follows: “Under the principle of universal jurisdiction, a state is entitled and even required to bring proceedings in respect of certain serious crimes, [23] irrespective of the location of the crime, and irrespective of the nationality of the victim or the perpetrator.” [24]

In recognition of the tension between universal jurisdiction and state sovereignty, universal jurisdiction is generally reserved for universal norms, such as the prohibition against genocide and crimes against humanity. However, in a post-9/11 world, a growing number of states have included WMD proliferation related activities as one potential objective element (actus reus) of the crime of terrorism in their national penal legislations. Moreover, some scholars have argued for the inclusion of terrorism (and terrorist activities) within the limited category of permissible subject areas for universal jurisdiction. Others, however, have argued against its inclusion, noting the lack of consensus on a definition for terrorism and the expansive power universal jurisdiction potentially gives to states. [25]

F. The Problem of Potentially Overlapping Jurisdiction

Although a state may have prescriptive jurisdiction under one of the five recognized bases described above, a question remains as to whether jurisdiction should be exercised by State A rather than State B where both can invoke one or more of the jurisdictional bases to support its claim.

In order to find a balance between competing jurisdictional clauses, international law holds first and foremost that a state’s exercise of jurisdiction must be “reasonable.” In order to determine whether a state’s exercise of jurisdiction is reasonable, Section 403 of the Third Restatement lists a number of factors which must be considered, including:

- the activity’s link to the territory of the state exercising jurisdiction;

- the connections between the regulating state and the person principally responsible for the regulated activity;

- the character and importance of the regulation to the regulating state;

- the existence of justified expectations which counter against regulation;

- the international importance of the regulation in question;

- the extent to which regulation is consistent with international tradition;

- the extent to which anther state may have an interest in regulation; and

- the likelihood regulation would cause conflict with another state. [26]

In the event of overlapping jurisdiction, under Section 403(3), each state must assess its claim in light of the factors listed above and the state with the weaker claim should defer to the state with the stronger claim. It is unclear whether this Section 403(3) purports to state a binding rule of international law or a non-binding principle of comity.

What weight one should give to each of the above factors, however, is still very much contested. Some commentators (e.g. Bassiouni) suggest a hierarchy among the types of national jurisdiction based upon a state’s link (or nexus) to the crime in question. Under this hierarchy, territorial jurisdiction receives the greatest weight, followed by nationality jurisdiction, and finally jurisdiction based on the effects principle. [27] Another approach is to weigh and compare the interests served. For example, under this model, the assertion of jurisdiction for serious crimes can prevail over jurisdictions based on allegations of a lesser crime. [28] Finally, some approach the question using a “first come, first served” approach, which gives priority to the state which first initiated proceedings.

While none of these rules for resolving jurisdictional conflicts are definitive, they are important to keep in mind as a limiting factor for this study. We looked only at whether a state’s prescriptive jurisdiction allowed for extraterritorial application of its laws. In a specific situation, the overlapping interests of another may prevent a state from exercising its jurisdiction.III. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

There were two phases to this study. During the first phase, the 1540 Matrices of 179 states were examined to determine whether or not a Member State reported extraterritorial application of its relevant laws. As noted earlier, the 1540 Matrices are the primary method used by the 1540 Committee to organize information submitted by Member States about their implementation of the resolution. [29] They are based upon the most recent national reports and official government information. The matrices used in this study were approved by the 1540 Committee in November and December 2010.

According to the official 1540 Committee website, matrices have not been completed for eight countries of potential interest to this study (although some of these states have submitted reports containing information that is not organized in accordance with the matrix format). They are: China (and China Taipei), Croatia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Malta, Philippines, Vatican City, and Vietnam. There are also no matrices for regional arrangements, such as the European Union. The extent of extraterritorial provisions in these states/regions thus could not be examined.

During phase two, 36 states that were identified during phase one as having some type of extraterritorial application were selected for more in-depth research. The 36 chosen were those that seemed to be of the greatest concern or relevance in non-proliferation terms. Below are some of the criteria used to narrow down the list of countries to thirty-six:

- A country is a powerful state, and is able to impose extraterritoriality as a matter of might as well as legal right.

- A country is a possible source country of WMD materials and technology, e.g., is a member of the Nuclear Suppliers Group.

- A country is highly compliant with its 1540 obligations overall, or specifically with respect to its obligation to criminalize non-state proliferation activities.

- A country poses particular proliferation risks because it is a possible or past WMD proliferator, is part of a cross-border ungoverned space, is a near or actual non-state, or is a country of transit, or a country of potential or actual WMD networked non-state proliferation.

For these thirty-six countries, we examined the national reports and addendums submitted by each, as well as the specific legislation referenced with respect to questions of extraterritorial application. In some instances, additional legislation beyond that mentioned by the state itself, such as a country’s penal code, was examined in an attempt to identify the jurisdictional basis for the extraterritorial claim.

IV. BASIC FINDINGS ABOUT EXTRATERRITORIAL APPLICATIONS OF LAW

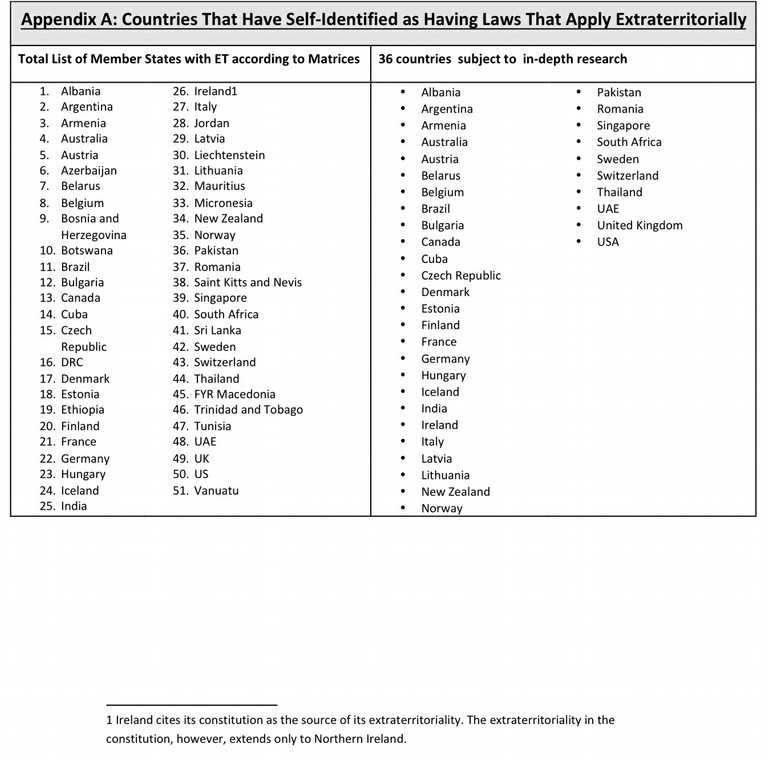

Only 51 of the 179 countries that have submitted reports indicated they have some type of extraterritorial application of their laws. [30] The 51 Member States are listed in Appendix A. These states did not assert extraterritorial jurisdiction equally to the three different types of weapons—chemical, biological and nuclear. While all but one state indicated that their legislation regarding chemical weapons had some form of extraterritorial application, [31] only 44 applied that same extraterritoriality to biological weapons and only 43 to nuclear. A complete breakdown of the states and when extraterritoriality applied is included in Appendix B.

For the thirty-six states that were examined in-depth, we found that for all of them, at least one basis for the exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction was the nationality principle. There were, however, differences in how that jurisdiction was defined and the breadth of its reach. Surprisingly, we found that almost half of the states also had provision for extending their jurisdiction extraterritorially under either the effects principle and/or, in certain limited circumstances, under the universal jurisdiction principle. In these instances, however, the exercise of such jurisdiction was tied directly to international treaties and law, for example, the prohibition against genocide. Penal codes were the most oft cited source of legislation for extraterritorial jurisdiction among the 36 states examined.

Each of the categories of jurisdiction is discussed in more detail below.

A. Territorial Jurisdiction

Every country in the first instance listed territoriality as the strongest basis for jurisdiction. In many countries, the territorial provisions addressed temporal concerns, i.e., which “phase” of a criminal transaction occurred on its territory. For example, in Armenia, territorial jurisdiction is exercised based not only upon where the crime has started, but also if it continued and/or finished in the Armenian territory. Belarus, similarly, has a temporal element to how it defines its territorial jurisdiction. If the crime started, continued or finished in Belarus, or if the crime occurred on the territory of Belarus in conspiracy with a person who committed it in a foreign country, then Belarus can exercise its jurisdiction over the person in question. [32]

In every case, the territoriality principle was specifically extended to ships, vessels and airplanes traveling under the flag of the specific state.

B. Nationality

Nationality was cited almost as often as territoriality as a basis for jurisdiction and was the primary mechanism through which states exercised extraterritorial jurisdiction. Within this category, however, there were numerous and varied definitions of what “nationality” meant. The vast majority of states included within nationality, not only citizens, but also those resident in the country, irrespective of whether the crime was committed within the country or somewhere outside. Switzerland is a typical example of this. Article 34 of Switzerland’s Federal Act on War Material of 13 December 1996 states that a person involved in “the development, manufacture, brokerage, acquisition, surrender to another, imports, export, transit, stockpiling, or any other form of possession of nuclear, biological or chemical weapons” is liable to up to ten years imprisonment. [33] It goes on to state that: “An act committed abroad is an offence in terms of these provisions irrespective of the law of the place of commission if: (a) it violates international law agreements to which Switzerland is a contracting part and (b) the offender is Swiss or is domiciled in Switzerland.” [34]

In a few cases, states have extended their jurisdiction to cover situations where a person acquires their citizenship after the crime, but before proceedings against them commence. For example, Austria’s legislation is applicable when the perpetrator is an Austrian national not only at the time of committing the offense, but also if he acquired the nationality later and still was a national during the trial, or had his domicile or general residence in Austria, or the offense has been committed by a legal entity having its seat in Austria. Like several other states in this study, Austria stipulates that its extraterritorial jurisdiction only applies when the acts in question are punishable by the territorial state as well. Iceland has a particular exception to this general caveat when the violation in question involves sanctions. Under its International Sanctions Implementation Act No. 93 (12 June 2008), Icelandic nationals can be held liable for violations committed abroad, even if the act is not punishable in accordance with the laws of the state where the violation was committed.

Some states specifically mentioned that dual citizenship did not act as a barrier to the state’s exercise of its jurisdiction.

The most unique application of the nationality principle in the study was the United States. The primary statutes responsible for regulating the export of commercial and dual use items in the United States—the Arms Export Control Act (AECA) and the Export Administration Act (EAA)—have been interpreted as applying extraterritorially, but not because of some type of broad definition of citizenship. Instead, extraterritorial jurisdiction under these statutes is derived from the U.S. nationality of the item or service exported from the United States. Thus, extraterritorial jurisdiction generally will be triggered when: (1) a foreign person has control of good or technology that originated in the U.S.; (2) the foreign person develops an item which contains parts or components that originated in the U.S.; or (3) the foreign person develops a product using U.S. technology. [35] The EAA also requires foreign persons to comply with re-export restrictions that prohibit the re-export of controlled items to countries for which a license would be required or to countries which are subject to a general prohibition or embargo by the United States. [36] The U.S. has frequently brought enforcement actions against foreign persons found to be in violation of these re-export restrictions. [37]

C. Effects-Based Jurisdiction

Effects-based jurisdiction was the second most cited form of extraterritorial jurisdiction, although less than half of the countries studied included it. Under this rationale, the state’s jurisdiction extends to activities outside a state’s territory that have a substantial impact on its territory or affect its national security. Unlike the nationality principle, which was often found in a state’s penal code, effects-based jurisdiction, when it existed, was almost always tied to a specific piece of legislation that dealt with a limited category of offenses. For example, New Zealand’s Terrorism Suppression Act of 2002 states that proceedings may be brought in a New Zealand court for acts that occurred wholly outside New Zealand but were done against a New Zealand citizen, a New Zealand state or government facility (e.g. embassy), or in an attempt to compel the Government of New Zealand to do or abstain from doing an act.

D. Passive Personality

Only 6 states based the exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction on the nationality of the victim or the crime. These include Albania, Armenia, Australia, Finland, New Zealand and the United Arab Emirates.

E. Universal Jurisdiction

Universal jurisdiction was mentioned by under half of the thirty-six states examined. Of those invoking universal jurisdiction, many included it in their penal codes with language that limited its application to international agreements/treaties that were “binding upon” the country. [38] For example, Article 6 of the Bulgarian Penal Code applies universal jurisdiction if a foreigner has committed a crime “against the peace and mankind.” The Penal Code does not specify what these two terms mean, but instead makes a reference to international agreements Bulgaria has signed.

Some states have specific statutes dealing with global terrorism or international crimes, which state that jurisdiction over such acts is universal. For example, Belgium has domestic legislation (passed in 1993 and amended in 1999) that allows Belgian courts to assert jurisdiction over grave breaches of the Geneva Convections of 1949 and Additional Protocol I and II (violations of International Humanitarian Law), as well as genocide and crimes against humanity. The location at which those offenses took place is irrelevant to the exercise of such jurisdiction. Moreover, the statute grants Belgium the power to try such crimes even in abstentia (without the presence of the suspect). New Zealand recently passed legislation granting it similar authority to prosecute international crimes under its International Crimes and International Court Act 2000. In contrast, Singapore has limited its exercise of universal jurisdiction to terrorist bombing offenses. Swedish courts, in contrast, have universal jurisdiction over any terrorist crimes, as noted in the Act on Criminal Responsibility for Terrorist Crimes.

None of the countries surveyed employed universal jurisdiction outside these very limited circumstances.

V. RESEARCH CHALLENGES AND LIMITATIONS

The study relied entirely upon the 1540 Matrices, the 1540 National Reports and the legislation listed therein. As a result, the study is limited by the accuracy of these documents. In a couple of instances, we found the legislation listed in the matrix either out of date or unrelated because it did not include a jurisdictional clause that applied the law extraterritorially. For example, in South Africa neither of the pieces of legislation listed pertained to either the control of WMDs or the exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction. In cases such as this, we looked to a country’s penal code and other legal provisions to see if we could deduce some basis for the extraterritorial claim.

Additionally, specific legislation was sometimes difficult to track down and/or inaccessible due to the lack of an English translation. Because the links provided in the 1540 Committee Legislative Database often did not work, we resorted to Google searches and other databases. Where English versions were not available, Google translate was used.

Finally, the study only looked at domestic sources for the application of laws extraterritorially. It is possible that regional commitments may exist that provide for extraterritorial application.

VI. CONCLUSION

Today, the threat of the use of WMDs by terrorist groups is one of the greatest threats challenging the global international security system. UNSCR 1540 was a collective effort to attempt to address this threat. It differs significantly from the existing non-proliferation multilateral treaty and arms control regimes (e.g. NPT, Chemical Weapons Conventions, etc.), as it reaches all WMD activities and particularly targets the proliferation of WMD to terrorists. If implemented fully, USNCR 1540 would impose a comprehensive set of obligations upon UN Member States to tackle non-proliferation activities and could potentially promote a culture of compliance in this area.

Amongst many other obligations, UNSCR 1540 calls on UN Member States to enact legislation and take effective measures to prevent non-state actors and terrorist groups from obtaining WMD. This paper attempts to draw conclusions as to what extent states have laws in place to criminalize non-state WMD proliferation activities extraterritorially. The study confirms that jurisdictional assertion continues to be primarily a territorial claim and is directly related to the notion of a state’s sovereignty. While states have clearly undertaken efforts to harmonize their legislation with UN Security Council Resolution 1540, it was beyond the scope of this paper to look at the key issue of enforcement of these laws.

The obligatory nature of UNSCR 1540 has raised the questions of its implementation, particularly as to what extent UNSCR 1540 trigged cooperation and actual compliance as opposed to assessing whether states simply have formal legal authorities to carry out their responsibilities under UNSCR 1540. Some scholars have also voiced a concern as to whether or not the Security Council has become a “world legislator” by passing 1540 Resolution with very broad general obligations and has replaced the conventional international law making process. This in turn opened up new debates about rule of law issues on international level, legitimacy of decision making and deliberative democracy within the UNSC. Those are all valid points and interesting avenues to conduct further research.

Irrespective of any criticism, UNSCR 1540 has considerably promoted and advanced awareness of the interest of international community in maintaining international peace through targeting non-state actor non-proliferation activities. The mere existence of extraterritorial control clauses in the national legal framework of reported countries is a valid indicator of that. However, there are still efforts to be done to create stronger legal cooperation in this field and to ensure that WMD do not reach terrorist hands. UNSC Resolution 1540 can serve as a strong complementary legal tool to other non-proliferation treaties to tackle illicit proliferation activities. Given the nature of this crime, it is important that states have laws and cooperation mechanism in force to prosecute crimes even beyond their borders in a manner that is consistent with the international law limitations on the exercise of extraterritorial prescriptive jurisdiction.VII. APPENDICES

Appendix B: Breakdown of the Type and Source of the Extraterritorial Application

1. Albania

2. Argentina

3. Armenia

4. Australia

5. Austria

6. Belarus

7. Belgium

8. Brazil

9. Bulgaria

10. Canada

11. Cuba

12. Czech Republic

13. Denmark

14. Estonia

15. Finland

16. France

17. Germany

18. Hungary

19. Iceland

20. India

21. Ireland

22. Italy

23. Latvia

24. Lithuania

25. New Zealand

26. Norway

27. Pakistan

28. Romania

29. Singapore

30. South Africa

31. Sweden

32. Switzerland

33. Thailand

Albania submitted its national report to UNSC 1540 Committee on 28 October, 2004.

The Republic of Albania is a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), as well as the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) and the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT). According to the article 122 of the Albanian Constitution, all international conventions and agreements after being ratified by the Albanian Parliament, are part of Albanian domestic legislative system and they prevail over domestic legislation.

Reported relevant domestic legislation includes Albanian Penal Code ((No. 7895, 27 January, 1995), Albanian Constitution (21 October, 1998), Law No. 9092 Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction (03 July 2003).

One of the key developments further to adoption of UN SC 1540 Resolution is passage of Albanian State Import-Export Control Law in 2007. The law controls activities in strategic goods and sets procedures for state export control over prevention of weapons of mass destruction.

Albania is not yet participating in some international regimes of arms control, such as Wassenaar Arrangement, Australia Group, Nuclear Suppliers Group, as well as not party to the Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation.

Argentina submitted its first national implementation report to 1540 Ad hoc Committee on 26 October, 2004. Further to this, Argentina submitted two additional reports on UNSCR 1540 implementation on 13 December 2005 and 5 July 2007 respectfully.

Argentina has ratified the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and acceded to NPT in 2005. It is also a State Party to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction (1993) and to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction (1972) together with Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (1996). Argentina is a subscriber state to the Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (2002).

As far as the regional cooperation is concerned, Argentina is also a state party to the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America (Treaty of Tlatelolco, 1967). Argentina has signed and ratified Vienna Convention on Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage (1966), as well as Convention on Early Notification of Nuclear Accident (1986), Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (1989), Convention on Nuclear Safety (1989).

Pursuant to Argentinean legal system all international treaties to which Argentina is a member state have the status of the highest law of the land, thus have supremacy over domestic law. Accordingly, Security Council resolution 1540 attains the same status as national legislation in Argentina.

Applicable domestic law includes Argentinean Penal Code (1989). Argentina has enacted Act No. 25,886 on 14 April 2004 to amend article 189 bis on supply of weapons in its Penal Code to supplement the definition of offenses covered by Security Council resolution 1540. In addition to its Penal Code and Constitution, Argentina has extensive domestic regulatory framework on weapons control of mass destruction.

Amongst those Argentina lists Weapons and Explosive Control Act No. 20,429 (1973); National Nuclear Activity Act No. 24,804 (1997); Transport of Hazardous Materials Act No. 24,449 (1999); Decree No. 1035 prohibiting the export of weapons (2001); Decree No. 603 creating the National Commission for the Control of Sensitive Exports and War Material (1992); Convention on Chemical Weapons Act No. 24,534 (1995); Weapons and Explosives Decree No.395 (1975); Ecological, Biological or Organic Production Act No. 25,127 (1999); Ecological, Biological or Organic Production Decree No 97/2001 (2001); Resolution 904/98 (1998) setting up Registry of Chemical Weapons; Transport of Hazardous Materials Act No. 24,449 (1994) and etc.

Major legal instrument governing export-import in Argentina is its Act No. 22,415 (Customs Code, 1981). Act No. 24,059 on domestic security and Act No. 25,520 on national intelligence govern border controls related issues.

As far as post UNSCR legislative measures are concerned, in its third follow up report submitted in 2007 Argentina has transmitted the passage of Act No. 26,247 on Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction. It fulfils Argentina’s obligation to enact national legislation according to Article 7 of the Chemical Weapons Convention.

Furthermore, with regard to import-export control legislation Argentinean Federal Public Revenue Administration issued resolution 1892. The latter adds contents of Chemical Weapons Convention schedules 1 and 2 to the María customs database system. This enables to check imports of such substances. The National Registry of Weapons (RENAR) has been given the authority to check and authorize all imports connected with the substances in schedules 1 and 2.

Argentine is a member to five sensitive export control regimes: the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the Australia Group (AG), the Wassenaar Arrangement (WA) and the Zangger Committee (ZAC). In 2005 Argentina joined Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI).

Armenia submitted its first and only national report to 1540 UNSC Ad hoc Committee on November 09, 2004. Additional to its national report, Armenia submitted additional document on measures she has taken to comply with 1540 obligations on 21 December, 2005.

Republic of Armenia is a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), as well as the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC). The Republic of Armenia has ratified the Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Materials on June 22, 1993.

Protocol Additional to the Agreement between the Republic Armenia and the International Atomic Energy Agency for the Application of Safeguards in connection with Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapon was signed on September 29, 1997 and entered into force from June 28, 2004.

In addition to international instruments, Armenian Parliament adopted new Penal Code in 2003 that covers the necessary aspects of counter proliferation issues. Parliament also passed a law on Export control of dual-use items and technologies and its transit across the territory of the Republic of Armenia on September 24, 2003. Armenian Law on Safe Utilization of Atomic Energy for Peaceful Purposes (March 1, 1999 with supplements as of April 18, 2004) is Armenia’s primary national nuclear law.

Within relevant domestic legislation one also finds Armenian Customs Code (adopted in 2001) which regulates import and export of certain goods and their means of transportation. Other applicable law is Law on Combating the Legalization of Proceeds from Crime and Financing of Terrorism, as well as Constitution and a number of governmental decrees.

Armenia is not a member of international export control regimes, such as Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), Zangger Committee, the Australia Group, and the Wassenaar Arrangement. Armenia is not a major supplier of controlled or military goods, materials and technologies. Armenia is a participant of Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI).

Armenian government has taken a number of legislative actions to accommodate 1540 UNSC resolution obligations. Those involve, amongst others passage of non-proliferation related governmental decrees and amending existing legislation, e.g. amending the Law on Licensing, supplementing Government Decree No. 762 of June 9,2005 on Approval of licensing procedure and form of license for use of nuclear materials, Government Decree No. 745 of June 9, 2005 on approval of licensing procedure and form of license for storage of nuclear materials, Government Decree N. 346 of March 24, 2005 on approval of licensing procedure and form of license for import to and export from the Republic of Armenia of nuclear materials, Government Decree No. 992 of July 27, 2005 (entered into force on August 18, 2005) on Adopting the Control list of dual use items and technologies and its transit across the territory of the Republic of Armenia.

4. Australia

On 28 October 2004 Australia submitted its first national implementation report to 1540 Ad hoc Committee. Further to the first report a supplementary one was submitted on 08 November 2005.

Australia has a wide range of legal instruments in place to combat WMD proliferation, including by non state actors. Most of the legislation predated the UNSCR 1540, but the majority has undergone amendments in recent years.

Australia is a state party to Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Materials (CPPNM), Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC), International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), adopted Additional Protocol to its IAEA Safeguards Agreements, as well as Nuclear Weapon Free Zone Protocols. In September 2005 the Australian Government also became a signatory to the International Convention for the Suppression of Nuclear Terrorism.

Primary national legislative framework covers Weapons of Mass Destruction Act (1995 as amended 2010), Nuclear Non-Proliferation (Safeguards) Act 1997, Chemical Weapons (Prohibition) Act (1994 as amended 2007), Criminal Code Act (1995 as amended in 2002), Crimes Act (1978), National Health Security Act (2007), Crimes (Biological Weapons) Act (1976, as amended in 2008 and 2010), Customs Act (1901) and Gene Technology Act (2000). Amongst those, e.g. Safeguards Act criminalizes possession of nuclear materials or associated item without permit. Criminal Code Act prohibits cross-border firearm trafficking, including disposal and acquisition of a firearm.

In addition to Customs Act (1901) Australia passed new custom control legislation, including Customs Amendment (Strengthening Border Controls) Act (2008) and Customs Amendment (Border Controls and Other Measures) Act (2009). The main legal mechanism controlling the export of items applicable for use in military and for WMD programs is Regulation 13E of the Customs (Prohibited Exports) Regulations.

Australia is a member of Zangger Committee (ZAC), Nuclear Supplier Group (NSG), Australia Group (AG), Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), Wassenaar Arrangement (WA) and Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI).

Austria submitted its first national implementation report on 28 October 2004. Following year (05 November 2005) Austria also transmitted its second national implementation report to 1540 Ad hoc Committee.

Austria has a wide range of international and domestic legislative measures in place to prevent the proliferation of WMD.

Austria has signed and ratified all relevant international non-proliferation instruments, such as the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction (BTWC), the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction (CWC).

Austria has also signed a Safeguards Agreement and an Additional Protocol to it with the International Atomic Energy Agency. The letter came into force for all EU members on 30 April 2004. The Additional Protocol in question is targeted to improve IAEA’s capacity to detect undeclared activities in the EU non-nuclear weapon states.

Additionally, Austria is a signatory to the Hague Code of Conduct against the Proliferation of Ballistic Missiles (HCOC).

The key regulatory domestic framework includes the Austrian Penal Code (1974), the Nuclear Non proliferation Act (1987), the Foreign Trade Act (1995, as amended in 2005), the War Material Act (1977) as amended in 2001 [41], Federal Constitutional Act for Non-Nuclear Austria (1999), Genetic Engineering Act (1994), Radiation Protection Act (1969, as amended in 2002), Radiation Protection Ordinance (2004), Foreign Trade Decree (as amended 20 October 2004), Nuclear Non-proliferation Act (1972). The Radiation Protection Act has undergone amendments in 2006 to reflect EU’s legislation on radiation protection, installation safety and handling radiation waste.

One of the legislative measures taken by Austria to comply with its 1540 obligations was to replace The Foreign Trade Act of 1995 by Foreign Trade Act of 2005 which entered into force on 1 October 2005. The new legal text regulates development, production, stockpiling, acquisition or retention of biological, chemical and nuclear weapons. Foreign Trade Act together with the War Material Act imposes controls on exports of weapons. Foreign Trade Act also regulates export of nuclear related dual-use items. On 5 May 2009 EC Regulation No. 428/2009 also set up Community regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use item.

As EU member, Austria also adheres and applies standards set by EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports and Licensing for exports of weapons to third countries.

As far as multilateral weapons and technology export control regimes are concerned Austria is a member to Zangger Committee (ZAC), Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the Australia Group (AG), Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), the Wassenaar Arrangement (WA), and Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI).

The Republic of Belarus submitted its first national implementation report to 1540 Ad hoc Committee on 20 October 2004. On 30 August 2005 Belarus presented its second report to provide additional information and respond questions raised by UNSC 1540 Committee.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union Belarus was the first country to voluntarily give up possession of its nuclear weapons. Accordingly, Belarus is a state party to the majority of international multilateral treaties and arrangements in the field of international nonproliferation regimes. Belarus is a state party to Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, Treaty on the Elimination of Medium- and Short-Range Missiles, Safeguards Agreement of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Materials, Nuclear Safety Convention and the Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation.

National legal framework includes a number of laws and regulations relating to specific issues raised by UNSCR 1540. The list, inter alia, covers Penal Code No. 225-3 (1999), Customs Code No. 130-Z (1998), Administrative Code 194-3 (2003) and Civil Code No. 218-? (1998). The Export Controls Act (1998) is the basic legislation regulating export controls. The Act sets out the legal bases and the powers of government agencies and legal and natural persons in within the export controls, as well as the purposes, fundamental principles and concepts of the export-control system and a schedule of controlled items (goods, services).

Other pieces of domestic regulatory regime includes the decree No. 94 on Certain Measures to Regulate Military and Technical Cooperation between the Republic of Belarus and Foreign States (2003), Presidential Decree on licensing of particular aspects of activity No. 17 (2003), Act No. 363-3 on the industrial safety of hazardous production facilities, Decision No 338 of the Council of Ministers on measures for the physical protection of nuclear materials (1993), Decision No. 34 of the Ministry for Emergency Situations on transport safety regulations governing the carriage of hazardous loads by rail transport, and Act No 1908-XII on state borders of the Republic of Belarus (1902).

Other legal instruments that postdated UNSCR 1540 are Act No 96-3 on the safety of genetic engineering (2006), Decision No 1049 of the Council of Ministers on the approval of the resolution governing the procedure for issuing licenses for the import, export or transit of opportunistic genetically engineered pathogens (2006), Decision No 46 of the Ministry for Emergency Situations on Regulations on a unified state system for accounting for and controlling sources of ionizing radiation (2006), Decision No. 461 on the import and export of chemicals subject to the control regime of the CWC (2006).

As far as Belarusian export import comport policy is concerned, Belarus is a party to the following non proliferation regimes: Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) and Zangger Committee (ZAC).

The Kingdom of Belgium has submitted two national implementation reports to the UNSC 1540 Ad hocCommittee (on 26 October 2004 and 6 December 2005).

Belgium is a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), as well as the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC). Belgium has ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), the Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), the Geneva Protocols of 1925 and the Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC).

Related domestic regulatory measures are the Constitution of the Kingdom of Belgium, the Penal Code Act approving the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction (10 July 1978), Act on terrorist offences (19 December 2003), Act on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purpose of money-laundering (11 January 1993), The Act of 20 July 1978 (amended by the Act of 15 April 1994 establishing the Federal Agency for Nuclear Control and relating to protection against ionizing radiation), The Act of 5 August 1991 on the import, export, and transit of and on combating trafficking in arms, munitions and equipment (as amended in 2003), Act of 14 March 1975 (NPT ratification), Council Directive 94/55/EEC and 96/49/EEC, EURATOM Regulation No 302/2005 of 8 February 2005, Council Regulation (EEC) No. 2913/92 of 12 October 1992 (Community Customs Code), Customs and Excise Act of 18 July 1997, as well as Council regulation (EC) n. 428/2009 of 5 May 2009 setting up a Community regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use items and etc.

According to Belgian penal legislation any person who stores, uses, transports, transfers those materials without due authorization is subject to criminal penalties (Penal Code, Art. 488b). The Belgian Act on Terrorist Offences (19 December, 2003) stipulates that the manufacture, possession, acquisition, transport or provision of nuclear or chemical weapons, the use of nuclear, biological or chemical weapons, and the research into and development of chemical weapons may also constitute a terrorist offense.

Belgium is an active member of multilateral export-control regimes, such as the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the Zangger Committee, the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), and the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies (WA) and the Australia Group (AG).

Brazil has submitted three full reports to the Ad hoc Committee on its national implementation of UNSCR 1540 obligations. First report was submitted on 29 October 2004, the others on 22 September 2005 and 17 March 2006 respectfully. International agreements to which Brazil is party have the same status as internal laws. Indeed, they are compulsory to State and non-State actors subject to national jurisdiction. Brazil’s international non proliferation obligations are derived from Treaty of Tlatelolco (Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean), Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction, Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction (BWC), Hague Code of Conduct, and Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material.

Brazil has incorporated all guidelines related to control and protection of sensitive materials, equipment and technology that may be used for the production of WMDs stipulated by international treaties in question.

Three legal instruments are essential to regulating non proliferation related activities. Those are the Federal Constitution 1988, the National Security Act No. 7.170 (December; 1983) and Heinous Crimes Act No. 8.072 (1990). E.g. National Security Act defines and penalizes crimes against national security, the political and social order, including those of terrorism, sabotage and transfer, storage and dissemination of military material.

Brazil has a number of by-laws and governmental regulations to deal with its 1540 obligations. Those include, but not limited to Decree No. 3.665 of November 20, 2000 (R-105) that determines the responsibility of the Brazilian Army in controlling products with destructive power or any other property that may pose a risk to natural and legal persons (arms, explosives, pyrotechnic materials, ammunition, parts and components). With regard to activities related specifically to the production, development and commercialization of materials and equipment that may be used in the fabrication of missiles, this control is exercised by the Army Command.

Relevant legislation as regards to means of delivery of WMD is contained in Decree No. 3.665 (2000, R-105). It establishes regulations for the adequate supervision of protection measures related to products under control (means of delivery, its parts and propellants).

Brazilian Act No. 6.453 (1977) establishes criminal responsibility for acts related to nuclear activities. It defines and penalizes the production, possession, supplying and use of nuclear material without necessary authorization, as well as export and import of nuclear material without due official license. In addition to this, Brazilian Act No. 9.112 of October 10, 1995 defines as sensitive goods all those goods with possible military applications; dual-use goods; and those that maybe used in nuclear, chemical and biological fields, as well as their means of delivery. It also establishes export controls on these goods and on services directly related to them.

One of the post UNSCR 1540 legal instruments is Act No. 11.254 (2005). It sets administrative and penal sanctions for activities prohibited by CWC. This legal instrument enables Brazil to fully comply with the CWC national implementation provisions.

Brazil is currently a member of Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR).

9. Bulgaria

Bulgaria has submitted two national implementation reports on its 1540 obligations (on 18 November 2004 and 10 March 2006). Bulgaria reports to have developed and implemented a number of legislative

measures related to the prevention of WMD proliferation.

Bulgaria is a member to the Treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT 1970), Chemical Weapons Convention (1997) and Biological Weapons Convention (1975), Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC), and has adopted an Additional Protocol to its IAEA Safeguards Agreement.

International instruments referenced above lay down non-proliferation commitments of Bulgaria. The latter treats obligations under its international agreements as part of its domestic legislation. According to the Bulgarian Constitution all international legally binding instruments which are duly ratified by the Parliament are part of the domestic legislation of the country. They have primacy over other acts of national law and supersede any domestic legislation which might be contradictory to their provisions.

The most relevant national legal framework includes the Penal Code (1968 as amended in 2005), Law on the Prohibition of the Chemical Weapons and Control over Toxic Chemicals and Their Precursors (adopted in 2000 and amended in 2007), the Law on Control of Foreign Trade Activity in Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies (adopted in 1996 and amended in 2010) and the Regulation for its Implementation (adopted in 2002 and amended in April 2004), Law on Measures against Financing Terrorist Activities (2003), the Law on the Safe Use of Nuclear Energy (2002, as amended in 2007), Regulations for Securing the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (2004), the Law on the Ministry of the Interior (1997), Law on Environmental Protection (2002, as amended in 2007) and the Law on Customs (1998, as amended in May 2004).

Bulgaria is a member of the following export control regimes: the Australia Group, Nuclear Suppliers Group, The Zangger Committee, the Wassenaar Arrangement, and Missile Technology Control Regime (since June 1, 2004). Following the UNSCR 1540, in May 2005 Bulgaria adhered to Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI).

Canada has submitted three reports to the 1540 Ad hoc Committee of UNSC. First report is dated 18 October 2004. The remaining two reports were filled on 19 January 2006 and 31 January 2008.

Canada is a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), as well as the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC). Canada has also ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), and Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC). All international obligations are implemented fully into national law of Canada.

Canada is also a signatory to the Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management (the Joint Convention), and the Convention on Nuclear Safety (CNS).

Key domestic regulatory framework is comprised of Nuclear Safety and Control Act (1997, c. 9), CWC Implementation Act (1995, c. 25), BTWC Implementation Act (2004, c.15, Part 23, assented, but not yet in force), Criminal Code (R.S. 1985, c. C-46), Chemical Weapons Convention Implementation Act, Customs Act ( 1985 as amended 2009 to enhance the powers of customs officers), Export and Import Permits Act (1985 as amended 2006, sections 24-26), Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act (1992, c. 5, as amended in 2009), Consumer Chemical and Containers Regulations (2001), as well as Canadian Environmental Protection Act (1999). Some of the more recent post 1540 UNSCR regulations cover Human Pathogens and Toxins Act (2009), Controlled Products Regulations (2008), Canada Border Services Agency Act (2005) and Transshipment Regulations (C.R.C, c. 606, 2010).

The Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA) is intended to regulate the use of nuclear energy and nuclear materials in Canada, including the implementation of relevant international measures to which Canada has agreed. Regulations made under the NSCA provide for the regulatory control and licensing of the production, use, storage and transport of nuclear materials, including their import and export.

Chemical Weapons Convention Implementation Act authorizes regulations regarding conditions for producing, using, acquiring or possessing a toxic chemical.

The Customs Act (R.S.1985, c.1) provides sections on enforcement and forfeitures that authorize the Canadian Border Security Agency to take enforcement and all necessary actions to prohibit the illicit trafficking in controlled goods.

The Export and Import Permits Act, R.S., c E – 17, was enacted by the Canadian Government to deal with the export of strategic and other goods. To this end, it satisfies the requirement for the establishment, development, review and the maintenance of appropriate effective national export and transshipment controls.

The Hazardous Products Act establishes an inspection regime. In addition, the Consumer Chemical and Containers Regulations (2001) it sets out requirements for the safe handling and storage of toxic chemicals.

The Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act (1992), and its associated regulations, sets out stringent requirements for the movement of, inter alia, flammable liquids, infectious substances, biological products.

Canada is a party to the following non proliferation regimes: Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), Australia Group (AG), Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), Zangger Committee (ZC), Wassenaar Arrangement (WA), Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), Container Security Initiative (CIS), Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism (GICNT) and G8 Director’s Group on Non-Proliferation.

11. Cuba

Cuba has submitted two national implementation reports to 1540 Ad hoc Committee (on 28 October 2004 and 23 December 2005).

Cuba is a state party to Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Materials (CPPNM), International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), as well as Nuclear Weapon Free Zone Protocols and the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (OPANAL).

In nuclear non proliferation field current domestic legislation of Cuba includes Decree-Law No. 207 on the use of nuclear energy (14 February 2000), Decree No. 208 on the State System of Accounting for and Control of Nuclear Material (24 May 1996), CITMA resolution No. 62/96 establishing rules for accounting and control of nuclear material (12 July 1996) and CITMA resolution No. 64/2000 entrusting the National Nuclear Safety Centre with the practical implementation of the State System of Accounting for and Control of Nuclear Material.

Decree-Law No. 207 of 14 February 2000 on the use of nuclear energy prohibits non-peaceful uses of any kind of nuclear material without proper authorization. Cuban Penal Code sets sanctions in form of imprisonment for those violations.

In biological field the primary legal instrument is the Decree-Law No. 190/1999 on biosafety, as well as No. 2/2004 on rules for accounting and control of biological material, equipment and related technology.

Similarly, Decree-Law No. 202/1999 on the prohibition of the development, production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons and on their destruction prohibits individuals or legal entities in the national territory or under the jurisdiction of the Cuban State from engaging in the production, use, stockpiling or transport of toxic chemicals or their precursors, unless they are intended for purposes not prohibited by the Chemical Weapons Convention and provided that the types and quantities used are compatible with those purposes.

Additionally, existing legislative measures also include Cuban Penal Code (1987), Act No. 93 against acts of terrorism (December 2001), Act No. 59/87 containing the Civil Code, Act No. 7/77 on civil, administrative and labor proceedings, Decree-Law No. 2000/99 on environmental offences, Decree-Law No. 107/88 on the control of industrial explosives, ammunition and explosive or toxic chemicals, and Decree-Law No. 154/94 establishing rules for the control of industrial explosives, ammunition and explosive or toxic chemicals. Further down the list is CITMA Resolution No. 180/2007, CITMA (Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment) Resolution No. 2/2004, Decree-Law No. 162/1996 (Customs Code), National Customs Service Resolution No. 19/2002 and etc.

Cuba is not a member of international export control regimes, such as Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), Zangger Committee, the Australia Group, and the Wassenaar Arrangement.

Czech Republic has submitted two national implementation reports to UNSC 1540 Ad hoc Committee (on 27 October 2004 and 23 January 2006).

Czech Republic is a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC), the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), the Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC) and Geneva Protocol of 1925.

Applicable national legislative measures referenced by Czech Republic include Act No. 281/2002 of 30 May 2002 on Some Measures related to Prohibition of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and to amend Trades Licensing Act, Criminal Code (Act No. 140/1961), Act No. 19/1997 On Some Measures Concerning Chemical Weapons Prohibition (as amended in 2000), Act No. 185/2004 (amending the Customs Code), Act No. 18/1997 (Atomic Act as amended in 2002), Act No. 13/1993 (Customs Act), Act No. 185/2004 (concerning Customs Administration), Council regulation (EC) No. 428/2009 of 5 May 2009 setting up a Community regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use items and etc.

Out of international control regimes, Czech Republic is a member of Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), Australia Group (AG), Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), Zangger Committee (ZC), Wassenaar Arrangement (WA) and Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI).

13. Denmark

Denmark filled its first national implementation report with the UNSC 1540 Ad hoc Committee on 27 October 2004. The second follow up report was submitted on 08 November 2005.

Denmark has ratified the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC); and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC). Hungary has also adopted an Additional Protocol to its IAEA Safeguards Agreement. Denmark is a party to Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC) and Geneva Protocol of 1925.

Relevant national legal measures to combat non-state WMD proliferation cover Danish Weapons Act, the Danish War Equipment Act, and the Danish Criminal Code, Radioactive Materials Act (1953), Act no. 443 of 14 June 1994 (about inspections, declarations and control according to the CWC), Chemical Substances and Products Act (Consolidated Act from the Ministry of Environment and Energy No. 21 of January 16, 1996), Radioactive Substances Act, n. 94(1953), Council Regulation No. 2913/1992 (Community Customs Code), Law no. 867 of 13 September 2005 (Customs Code), Council regulation (EC) No. 428/2009 of 5 May 2009 setting up a Community regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use items and etc.

Following the UNSCR 1540 adoption Denmark passed Act No. 555 on 24 June 2005 to amend the Weapons Act. Denmark has introduced a new set of rules concerning arms brokering and technical assistance in relation to chemical, biological or nuclear weapons and missiles specifically elaborated or modified for the delivery of such weapons. Furthermore, rules on intangible transfer of software and technology regarding weapons have been introduced. These rules took effect on 1 July 2005.

Denmark is also an active member of the multilateral export control regimes: the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group (NSG), the Zangger Committee (ZC), the Australia Group (AG), the Missile Technology Control Regime MTCR) and the Wassenaar Arrangement (WA), as well as Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI).

UNSC 1540 Ad hoc Committee received Estonia’s national implementation report on 29 October 2004.

Estonia is a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), as well as the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC). Estonia has also ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear- Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), and Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC).

Applicable domestic primary regulatory framework is comprised of Estonian Constitution (1992), Penal Code (2002), Strategic Good Acts (2004), and Customs Act (2004). Strategic Goods Act (2004) prohibits the export and transit of weapons of mass destruction, any materials, hardware, software and technology used for the manufacture of weapons of mass destruction, and the export and transit of antipersonnel mines, and services related thereto regardless of their country of destination.

Related secondary legislation includes Statutes of Strategic Goods Commission Regulation No. 26 of the Government of the Republic of Estonia (2004), Customs Procedures related to Strategic Goods and Procedure of Intra-Community Transfers, Regulation No. 257 of the Government of the Republic of Estonia (July 2004), Environmental Monitoring Act (as amended in 2005), Chemicals Act (as amended in 2007), Environmental Impact Assessment and environmental management System Act, 2005 and Radiation Law (as amended in 2007).

Estonia is a member of the following export control regimes: Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), Australia Group (AG), and Wassenaar Agreement. Estonia is also a Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) participating state.

Finland submitted its first report on national implementation of 1540 obligations to the Ad hoc Committee on 28 October 2004. The first report was further supplemented by additional reports on 05 December 2005 and 27 February 2006. Its latest report Finland filed on 20 April 2011.

Finland is a state party to key international non-proliferation arrangements: the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) as well as the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Finland has also adopted an Additional Protocol to its IAEA Safeguards Agreement.

Finland has a wide range of legislative measures to prevent the proliferation of WMD, including by non-state actors. The key regulatory framework includes the Nuclear Weapons Act (203/1970), the Biological Weapons Act (257/1975), the Chemical Weapons Act (346/1997), the Nuclear Energy Act (990/1987), the Act on the Control of Exports of Dual-Use Goods (562/1996) and the Penal Code (33/1989), Customs Act (1466/1994) and their amendments [42]. There have been a number of amendments to those laws to accommodate issues raised by UNSCR 1540.

Some recent regulations are the Government Decree on Security in the Use of Nuclear Energy (734/2008) issued in 2008, as well as Finland’s accession to the International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism in 2009. In 2007 Finland also joined the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism.

Finland is also an active participant in all the export control regimes, including the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the Zangger Committee, the Australia Group (AG), and the Wassenaar Arrangement (WA). Finland is also a participant state to Proliferation Security Imitative (PSI).

France submitted two reports on measures she has taken to implement obligations set by UNSCR 1540. First report was submitted 28 October 2004 and the second one filled on 25 August 2005.

France is a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), as well as the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC). France has ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), the Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), the Nuclear Weapons Free Zone Protocols and the Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC).

France has an extensive national legal framework in place to combat proliferation of WMD. Primary domestic regulations referenced by France in its national reports are French Penal Code (1994 as amended 2005), the Code of Public Health (as amended by Law 75-17), Law concerning the transportation by railway, road or inland navigation of dangerous or infected materials (5 February 1942), Council Regulation 2913/1992 (Community Customs Code), French Defense Code, French Customs Code, Labor Code, Environmental Code, Decree No. 98-36 of 16 January 1998, Council Regulation (EC) No 428/2009 setting up a Community regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use items (5 May 2009) and etc.

France has adopted subject specific acts targeted towards non proliferation of biological, nuclear, chemical weapons. Act No. 72-467 prohibits the development, production, possession, stockpiling, acquisition and transfer of biological or toxin-based weapons prohibits the foregoing activities in connection with biological weapons or agents which might be used in their manufacture.

Further to 1540 UNSCR, France has repealed Act No. 80-572 of 25 July 1980 that was intended to prevent and, where necessary, detect without delay any disappearance, loss, theft or diversion of nuclear material in French territory. The revised provisions of the law in question have been incorporated into the Defense Code (articles L. 1333-1 to L. 1333-13).

France also used to rely on Act No. 98-467 of 17 June 1998 to fulfill its obligations under Chemical Weapons Convention. This was also repealed on 20 December 2004. The legal provisions in question have been also incorporated into the Defense Code (articles L. 2342-1 to L. 2342-84).

In France the physical protection of installations presenting a risk of proliferation is governed by Ordinance No. 58-1371 of 29 December 1958 on the strengthening of the protection of vitally important installations.

France is an active member of the various export control regimes for sensitive materials, equipment and technologies. Those are Wassenaar Arrangement (WA), Australia Group (AG), Zangger Committee (ZC), Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), Proliferation Security Initiative

(PSI), as well as Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism.

The Federal Republic of Germany has submitted two national implementation reports to the 1540 Ad hocCommittee (on 6 October 2004 and 4 October 2005).

Germany reports to have a number of policies and national and international legal framework to combat WMD proliferation and their means of delivery by non-state actors. Germany is party to all relevant multilateral disarmament, arms control and non-proliferation treaties and conventions. Those are the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC), the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM) and Hague Code of Conduct (HCOC).

The basic regulations on manufacture transport and marketing of war weapons are contained in the War Weapons Control Act established in 1961 in response to art 26 of the German Constitution (Basic Law), where all actions to develop, transport or market war weapons are prohibited unless explicitly approved by the Federal Government.

The War Weapons Control Act (1961) provides for a comprehensive framework; the Foreign Trade and Payments Act (2009), the War Weapons Reporting Ordinance and the Implementation Act on the Convention on the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons as well as the Implementation Act on the Convention of 10 April 1972 on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons further complement the War Weapons Control Act [43].

Other laws relevant for the prohibition of development, acquisition, production, possession, the transport, transfer or use of nuclear, chemical or biological weapons and their means of delivery are the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance of 18 December 1986, as well as the directly applicable Council regulation (EC) No. 428/2009 of 5 May 2009 setting up a Community regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use items.