by Desmond Ball, Bill Robinson and Richard Tanter

14 August 2015

The full report is available here

I. Introduction

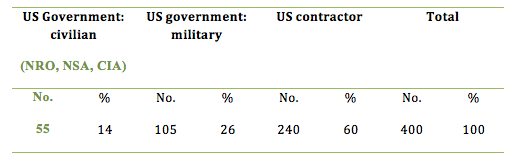

Many Australians associate Pine Gap with the Central Intelligence Agency, and it probably remains the CIA’s most important technical intelligence collection station in the world. Yet Pine Gap is much more thoroughly militarised than in the past, with units of all four branches of the US armed forces now present, with close involvement in operations of the US military worldwide, including in Iraq and Afghanistan. The US military personnel now comprise about 66 per cent of the US Government employees (not counting contractor personnel) at Pine Gap. US military Service elements form a Combined Support Group (CSG). Through the 1990s, the growing Service presence supported Pine Gap’s primary (and during that period its sole) role, that of controlling and processing and analysing SIGINT collected by the NRO/CIA geosynchronous SIGINT satellites. Since then, the larger proportion of the CSG personnel have evidently been engaged in FORNSAT/COMSAT (Foreign Satellite/Communications Satellite) collection. Officially, they are engaged in Information Operations, Cyber Warfare and the achievement of Information Dominance. In practice, this involves monitoring Internet activities being transmitted via communications satellites, scouring e-mails, Web-sites and Chat Rooms for intelligence to support military operations, and particularly those involving Special Operations Forces, in Iraq and Afghanistan. They are undoubtedly key participants in NSA’s X-Keyscore program at Pine Gap.

Desmond Ball is Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University (ANU). He was a Special Professor at the ANU’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre from 1987 to 2013, and he served as Head of the Centre from 1984 to 1991.

Bill Robinson writes the blog Lux Ex Umbra, which focuses on Canadian signals intelligence activities. He has been an active student of signals intelligence matters since the mid-1980s, and from 1986 to 2001 was on the staff of the Canadian peace research organization Project Ploughshares.

Richard Tanter is Senior Research Associate at the Nautilus Institute and Honorary Professor in the School of Political and Social Sciences at the University of Melbourne.

II. Special Report by Desmond Ball, Bill Robinson and Richard Tanter

The militarisation of Pine Gap:

Organisations and Personnel

The Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap, located just outside the town of Alice Springs in Central Australia and managed by the US National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), is one of the largest US technical intelligence collection facilities in the world. Pine Gap today hosts three distinct functions and operational systems. Its original and still principal purpose is to serve as the ground control station for geosynchronous signals intelligence (SIGINT) satellites. Secondly, since late 1999 Pine Gap has hosted a Relay Ground Station (RGS), which relays data from US missile launch detection/early warning satellites to both US and Australian HQs and command centres. Finally, Pine Gap appears to have acquired a FORNSAT/COMSAT (foreign satellite/communications satellite) interception function in the early 2000s.

Many Australians associate Pine Gap with the Central Intelligence Agency, and it probably remains the CIA’s most important technical intelligence collection station in the world. Yet Pine Gap is much more thoroughly militarised than in the past, with units of all four branches of the US armed forces now present, with close involvement in operations of the US military worldwide, including in Iraq and Afghanistan.

On 22 March 1967, at a meeting with Alice Springs residents, Richard Stallings, the first chief of the Pine Gap facility, said that there would be ‘no serving military officers or men at the site’.[1] This remained the case for more than two decades, until late in 1990, when a small group composed of both US and Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel arrived at the facility in preparation for Operation Desert Storm in Kuwait and Iraq. According to David Rosenberg, who worked at Pine Gap as a civilian ELINT Analyst for the NSA from 1990 to 2008, the small military presence ‘wasn’t visually obvious because Pine Gap had (and still maintains) a No Uniforms policy. When the soldiers first arrived, they were asked to “blend in” with the local community’.[2]

However, there was a major increase in Service personnel, involving Navy, Air Force and Army personnel, around 1998-99. It amounted to about 100 personnel, or about a quarter of the total US personnel at the facility. These Service elements formed a Combined Support Group (CSG). Through the 1990s, the growing Service presence supported Pine Gap’s primary (and during that period its sole) role, that of controlling and processing and analysing SIGINT collected by the NRO/CIA geosynchronous SIGINT satellites, at that time being the Magnum satellites launched in January 1985 and November 1989. Some of those who arrived in 1998-99 and subsequently have undoubtedly also been involved with this program, garnering operational intelligence as the SIGINT satellites monitor ground-based emitters (including mobile phones) in areas of interest.

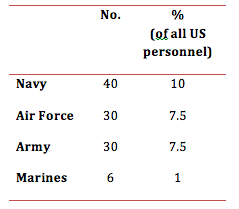

The larger proportion of the CSG personnel who arrived around 1999-2000, and those since, have evidently been engaged in FORNSAT/COMSAT collection, initially as part of NSA’s Echelon program. This activity is strictly compartmentalised from the CIA and NSA civilian operators and analysts in the main Operations Room. Officially, they are engaged in Information Operations, Cyber Warfare and the achievement of Information Dominance. In practice, this involves monitoring Internet activities being transmitted via communications satellites, scouring e-mails, Web-sites and Chat Rooms for intelligence to support military operations, and particularly those involving Special Operations Forces, in Iraq and Afghanistan. They are undoubtedly key participants in NSA’s X-Keyscore program at Pine Gap. The US military personnel now comprise about 66 per cent of the US Government employees (not counting contractor personnel) at Pine Gap.

Table 1. US personnel at Pine Gap, 2015

Table 2. US military personnel at Pine Gap, 2015, by service

The beginnings, 1990-98

The first US military contingent at Pine Gap arrived around September 1990, during the build-up for Operation Desert Storm. Rosenberg, who began working in the Operations Room on 5 October, has recorded that, just as he arrived, ‘for the first time, Pine Gap was experiencing a long-term deployment of military personnel to supplement the previous ‘civilian-only’ Operations population’. He has also stated that ‘the newly-arrived American and Australian military contingent (about five when I arrived) proved to be a capable, dedicated and useful resource that supplemented the civilians who historically occupied every billet within Operations’. He states that ‘the military at Pine Gap’ played an important role in providing the US forces with ‘advance intelligence about Iraq’s military posture’, and that they ‘had a different perspective from the civilians as they were trained in warfare’.[3]

Further Service personnel arrived in the mid-1990s, including members of the US Navy’s then SIGINT organisation, the Naval Security Group (NSG). For example, Petty Officer Karen Bramell, a Navy Cryptologic Technician and Signals Analyst, arrived at Pine Gap in 1996, serving there until 1998.[4] Her last assignment in the Navy, from 2009 to 2011, was with the office of the Department of Defense (DoD) Special Representative Japan (DSRJ) at Yokota Air Base, formerly called the NSA Representative in Japan.

On 6 February 1997, the Minister for Defence, Ian McLachlan, announced a substantial staff increase at Pine Gap. Whereas there were 725 personnel at the station in February 1997 (an increase of about 60 over the previous six years), it was anticipated that this number would grow to about 895 (420 Australians and 475 US personnel), an increase of 170 by 2000. The Minister stated that ‘the staff increases, to be phased in over a number of years, involve civilian and military personnel from both Australia and the United States’.[5] The Minister’s announcement reflected a major reorganisation of the NRO’s management structure at Pine Gap (as well as at other NRO facilities, such as those at Menwith Hill in Yorkshire and Buckley Air Force Base in Colorado) in 1997.

Figure 1. Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Karen Bramell, NSG Det Alice Springs, 1996-98

Source: ‘Brammel, Karen, SCPO’, TogetherWeServed.com, at http://navy.togetherweserved.com/usn/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=ShadowBoxPersonPhoto&type=PersonExt&filter=All&order=Sequence_desc&maxphoto=4&show_grid_View=0&ID=21077&selectedPhotoID=1182586.

The Service Cryptologic Agencies (SCAs) at Pine Gap

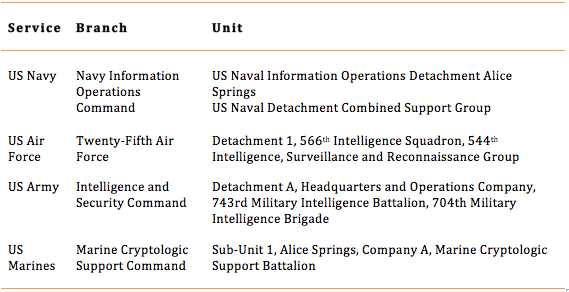

The reorganisation of the management structure in 1997 involved the establishment of Special Collection Elements (SCEs), composed of personnel from not only the CIA but also the National Security Agency (NSA) and Service (Army, Navy and Air Force) Cryptologic Agencies (SCAs). In the case of the US Navy, for example, a Naval Security Group (NSG) Detachment was established, with three officers and 40 enlisted sailors, in March 1998.[6] There is also a detachment of the US Army’s 743rd Military Intelligence Battalion, a detachment of the US Air Force’s 566th Intelligence Squadron, and Sub-Unit 1 of the US Marines’ Cryptologic Support Battalion. These Service personnel formed a Combined Support Group (CSG), which is officially designated RUHDSGA for cable routing purposes.[7]

Table 3. Special Collection Elements resident at Pine Gap

There have been around 105 US Service personnel at Pine Gap since 1999-2000, including 6-8 junior officers. The NAVDET had three officers and 33 enlisted sailors on 15 October 1999.[8] NIOD Alice Springs had 37 sailors, together with perhaps three officers, in June 2013.[9] The Air Force unit, then known as Detachment 2 of the 544th IOG, had 28 airmen, together with one or two officers, in 2005-07.[10] The detachment of the 743rd MI Battalion had 30 soldiers at Pine Gap in 2007.[11] The Marine sub-unit presumably has around six members, in order to provide two per shift.

Scrutiny of the US military personnel deployed at Pine Gap illustrates the importance of a Pine Gap posting in careers in all four services, and pathways that link Pine Gap to postings in combat zones in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the rapidly developing Africa Command, as well as to other key SIGINT facilities and cryptological or cyber units in the US homeland and in Japan and South Korea.

NIOD Alice Springs commanders have gone on to senior positions or command at NIOC Hawaii, NIOC Sugar Grove, and NSG Command, as well as at the Center for Naval Cryptology and the Center for Information Dominance, both in Pensacola, Florida. A senior Enlisted Leader at Pine Gap in recent years had previously had postings at the White House, NIOC Maryland and NIOC Georgia. Commanders of the Air Force detachment at Pine Gap have gone to the Joint Staff and the Office of the Secretary of Defense, as well as to head ISR operations in Special Operations Command Africa. A commander of the Army detachment at Pine Gap, a space systems engineer, went to a major role in the creation of US Army Cyber Command, and as a civilian, as NRO representative to Africa Command for ‘all satellite programs for the African continent’, making a second direct Pine Gap career link to US special forces operations and drone operations in combat areas outside legally sanctioned war zones.

The remainder of this Special Report is available in the full PDF version here.

III. References

Cover image: ‘Welcome to NIOD Alice Springs’, NIOD ALICE SPRINGS NT AS, US Navy, at http://www.public.navy.mil/fcc-c10f/niodas/Pages/default.aspx.

[1] ‘Official Gives Facts on Space Base’, Centralian Advocate, 23 March 1967, p. 1; and ‘Alice Springs Centre to be “Unobtrusive”’, Northern Territory News, 23 March 1967, p. 1.

[2] David Rosenberg, Inside Pine Gap: The Spy Who Came in From the Desert, (Hardie Grant Books, Melbourne, 2011), pp. 54-55.

[3] Ibid., pp. 65-67.

[4] ‘Bramell, Karen, SCPO”, TogetherWeServed.com, at http://navy.togetherweserved.com/usn/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=AssignmentExt&ID=61370.

[5] Ian McLachlan (Minister for Defence), ‘Staff Increases at Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap’, Media Release MIN 34/97, 6 February 1997, at http://www.defence.gov.au/media/1997/03497.html.

[6] Memorandum from Commander, Naval Security Group Command, Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, to the Chief of Naval Operations, ‘Request for the Establishment of U.S. Navy Detachment (NAVDET) Combined Support Group (CSG), Alice Springs, Australia (AUS)’, 29 January 1998; and Cameron Stewart, ‘Top US Spy Unit Sent to Pine Gap’, The Weekend Australian, 26-27 January 2001, pp. 1-2.

[7] ‘Allied Routing Indicator Book: Canada-United States Supplement 1(P)’, May 2014, at http://jcs.dtic.mil/j6/cceb/acps/canus-supp/A117_s1_021.pdf.

[8] United States Department of the Navy, ‘Navy DET Combined SUPGRUAUS’, at http://publicdirectory.smartlink.navy.gov.us.

[9] ‘CPO-365 Alice Springs Honor Our Shipmates’, Anchor Watch, June-July 2013, p. 8, at http://www.public.navy.mil/fcc-c10f/niocmd/AnchorWatch/AW_2013_06.pdf.

[10] Jeff Ford, LinkedIn, at https://www.linkedin.com/in/jeffreyford97.

[11] Buckley Air Force Base: 2007 Telephone Guide & Directory, p. 22, at http://ebooks.aqppublishing.com/archive/base_guides/Buckley.pdf.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.