By Peter Hayes

March 21, 2017

I. INTRODUCTION

This essay by Peter Hayes analyzes the significance of US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s statements that Japanese and South Korean nuclear proliferation are “on the table” in negotiations with China over what to do about North Korea. Hayes concludes that: “Tillerson’s playing the nuclear compellence card was not only strategically unsound, but vacuous. The notion that the Chinese can be herded by cracking a whip or softened up in advance of the presidential summit on such a complex and important issue is absurd.”

Peter Hayes is Executive Director of Nautilus Institute and Honorary Professor at Centre for International Security Studies at Sydney University.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Roger Cavazos, Chung-in Moon, Masakatsu Ota, Lee Sigal, Richard Tanter for review comments. The author is solely responsible for any errors and interpretation.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

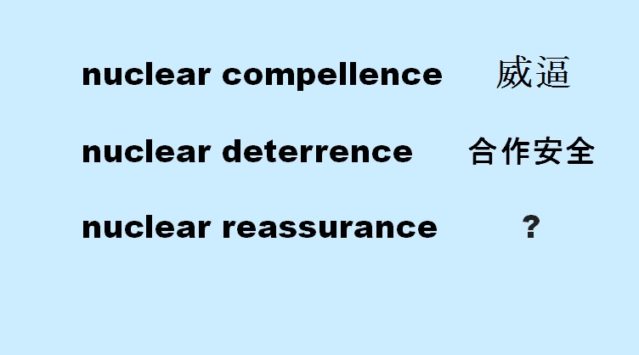

Credit: Banner text is based on translations by the English-Chinese Nuclear Security Glossary published by the US National Academies’ Committee on International Security and Arms Control. There is no direct translation of nuclear reassurance, part of the lingo of western deterrence theory, although “reassurance” is contained in the English phrase for cooperative security and translating into Chinese as 合作安全

II. SPECIAL REPORT BY PETER HAYES

PLAYING THE JAPAN NUCLEAR CARD: DID THE US SECRETARY OF STATE REVERSE FIVE DECADES OF US NON-PROLIFERATION POLICY?

MARCH 21, 2017

1. Background

Since the United States halted South Korean nuclear proliferation in the nineteen seventies,[1] and abandoned any serious consideration of promoting Japanese nuclear proliferation (due to the Kissinger-Nixon drive to open relations with China from 1969 onwards[2]), US policy has opposed any pretension by its East Asian allies that they acquire their own nuclear weapons. This stance included shutting down Taiwan’s nuclear weapons program in the nineteen eighties.

On his just completed visit to East Asia, the US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson seems to have signaled that this policy has or is about to change. He did so in an interview with Fox News while he was at the DMZ on March 17, 2017; and a subsequent interview with Independent Journal Review on his flight from Seoul to Beijing released on March 18, 2017.

2. The DMZ Fox interview

The Fox story bears close inspection of the kind that one must assume it has gotten already from Japanese, Korean (both sides) and above all, Chinese analysts even before he left Korea and landed in China for his meetings with Wang Yi on March 19, 2017.

In typical Fox spin, the headline and introduction to the story are misleading.[3] In the lead up to the actual interview, the Fox anchor suggests that Secretary of State Tillerson referred to the nuclearization of East Asian allies, that is, ROK and Japan. But the actual question put to him and therefore the subject of his response was with respect to the Korean Peninsula only. Also, the Fox anchor says that he was asked if “US allies, Japan and South Korea, should beef up their forces here including [Fox’s emphasis] nuclear weapons?”

But the actual question asked of Secretary of State Tillerson referred only to “nuclearization of the Peninsula as was discussed during the campaign.”

Nuclearization of the Peninsula has two meanings. The first, not discussed by Trump during the campaign at all, is to reintroduce nuclear weapons, which is a prerogative that then-Secretary of State Colin Powell reserved for the United States at the time of withdrawal of US tactical nuclear weapons from the ROK under then President Bush senior in 1991. In recent years, it has apparently been put on the table by the ROK in various official fora; was rejected by Obama Administration officials on the record in 2016 although they also stated that it was up to the ROK as a sovereign state to request such redeployment, with the further implication that there was no assumption that the United States would do so. Such redeployment is reportedly now part of the Korea policy review set of options under consideration by the Trump Administration.

The other meaning during the campaign was that the ROK and/or Japan might do well to arm themselves with nuclear weapons, that is, to go it alone, and that the United States would be better off if they did so. Trump later denied making such statements but fact-checking leaves no doubt that he in fact made them.[4] In principle, Japan and the ROK could also “share” American nuclear weapons, for example, on the NATO model (although doing so would require Congressional approval).

But contextually, it is clear that Trump’s campaign statements were not nuanced; and that he meant that the ROK and Japan might do well to go nuclear on their own (presumably on the UK model, although he did not address the kind of relationship nuclear-armed allies in East Asia would have with the United States leaving open two broad options: maintaining the military alliance presumably on the British model, or rupturing the military alliance while remaining aligned, the French model.

Presumably the best possible outcome would the creation of a formal Northeast Asian Treaty Organization of three allied nuclear weapons states with a joint military command led by the United States. However, given Korea’s antagonistic history with Japan and its geo-strategic location in relation to China, it is doubtful that a nuclear-armed ROK or nuclear-armed re-unified Korea would have any interest whatsoever in allying itself with Japan, even under American leadership, and that this concept is completely illusory. The model of the more loosely integrated and now dissolved Southeast Asia Treaty Organization is even less salient to Northeast Asia today than NATO. Indeed, as two scholars put it, the “obstacles to creating such an institution are as large as to render it a mere fantasy.”[5] Thus, the implicit trilateral logic of a nuclear-military alliance would reduce to what Michael Green called “a virtual alliance” that signals to China that North Korea risks bring about a “burgeoning NATO-type political security arrangement.”[6]

Although the actual question put to Secretary of State Tillerson by the Fox interviewer didn’t refer to Japan or East Asian allies, many analysts believe that if the ROK goes nuclear, then the political conditions in which that would take place would almost certainly make Japan follow suit, although there are contrary arguments.

It is incredible that the ROK has put nuclear proliferation on the table. The ROK isn’t that uncouth or stupid. ROK officials have also explicitly declared recently that they intend to remain a non-nuclear weapons state. Thus, if it is on the table, it wasn’t the ROK that put it there.

Yet, Secretary of State Tillerson wouldn’t say it’s on the table; he wouldn’t say it’s off the table. He did say nothing has been taken off the table. So is it there already? It is unimaginable that the United States has put South Korea obtaining its own nuclear weapons on the table in the extended deterrence committee or other contexts since the inauguration of the Trump Administration. So if it is not there now, why not reiterate existing US policy, which is that it isn’t on the table, period? Or, was he suggesting a that he would put it on the table in the future unless…?

This phrase would shift US policy from strategic clarity on allied proliferation to strategic ambiguity.

Uttered at the Demilitarized Zone, the only reasonable conclusion is that he played Trump’s nuclear proliferation card, deliberately. If Tillerson had left it at this nebulous phrasing, no-one in Japan or beyond would have paid much attention.

3. The Independent Journal Review interview

Until March 18, 2017 when the Independent Journal Review released the transcript of journalist Erin McPike’s interview with Secretary of State Tillerson.[7] In this interview, he doubled down on the threat and made it explicitly about Japan (EM is the interviewer):

EM: You told Fox yesterday that ‘nothing is off the table’ with respect to the nuclearization of the Korean peninsula. In your confirmation hearing, you kind of said that South Korea and Japan don’t need to have nuclear weapons. Has your view changed, given the urgency of the situation with North Korea, particularly because Japan could finalize development of a nuclear weapon rather quickly if they needed to?

RT: No, it has not, nor has the policy of the United States changed. Our objective is a denuclearized Korean peninsula. A denuclearized Korean peninsula negates any thought or need for Japan to have nuclear weapons. We say all options are on the table, but we cannot predict the future. So we do think it’s important that everyone in the region has a clear understanding that circumstances could evolve to the point that for mutual deterrence reasons, we might have to consider that. But as I said yesterday, there are a lot of … there’s a lot of steps and a lot of distance between now and a time that we would have to make a decision like that. Our objective is to have the regime in North Korea come to a conclusion that the reasons that they have felt they have had to develop nuclear weapons, those reasons are not well-founded. We want to change that understanding. With that, we do believe that if North Korea [were to] stand down on this nuclear program, that is their quickest means to begin to develop their economy and to become a vibrant economy for the North Korean people. If they don’t do that, they will have a very difficult time developing their economy. [8]

This interview quickly led to a Japan Times article that cited various commentators’ speculations about Secretary of State Tillerson’s motivations in making such comments. These ranged from suggestions that he was poorly briefed, thinking out loud, stating the obvious, repeating past speculations to this effect by American officials (specifically, those by Cheney and others in the early 2000s), staying aligned with his boss, preparing the ground for the Xi-Trump talks in April 2017, making an outright mistake (“lack of internal discipline”), and, indicating a possible rupture with past policy.[9]

His phrasing does not speculate vaguely about the future in which allies might choose of their own volition to go-it-alone with nuclear weapons. Rather, he states that “we” (the United States) may consider that Japan should become nuclear-armed in order to bolster “mutual deterrence.” This wording suggests that the United States may shift to a pro-proliferation stance, promoting proliferation. That is, this is an active option now on the table, put there not by South Korea or Japan, but the United States.

Tillerson does not explain how or why Japanese nuclear weapons would enhance “mutual deterrence” against the DPRK better than American nuclear weapons. Ironically, his phrasing suggests that a deterrence “deficit” already exists under the US nuclear extended deterrence arrangements with its allies, directly contrary to the extensive efforts made by the United States in the last five years to reassure Japan and South Korea that no such gap exists. The use of the word “mutual” is also strange in this context as the United States has worked hard to avoid admitting that US-Chinese, let alone US-North Korean, nuclear deterrence is “mutual” in the sense that the United States and the former Soviet Union converged on a common understanding about the mutuality of strategic nuclear deterrence. In effect, Secretary of State Tillerson is attributing deterrence power to the DPRK’s nuclear arsenal, which is not only needless but an admission of North Korea’s claims as to the efficacy of its campaign of nuclear threats. These inept and shoddy phrasings suggest that Tillerson was indeed ill-prepared in issuing this compellence threat or was following a narrative constructed in the White House by inexperienced political appointees as has occurred on other important policy issues in the Trump Administration.

4. The target of the nuclear compellence threat

Who is the main target of a threat to unleash the allies to arm with nuclear weapons? Surely not South Korea where rumblings about independent proliferation which are either domestic chest thumping by politicians or are aimed at putting pressure on China (as Chung Mong-joon, one of the main advocates of the ROK going nuclear avers; good luck with that!). Presumably not North Korea which is notoriously unconcerned about the proliferation impacts of its nuclear weapons program and outrageous nuclear threats on its neighbors.

Undoubtedly, Secretary of State Tillerson’s main target is China, whose leaders are indeed profoundly worried at the prospect of Japanese nuclear weapons proliferation – and a possible chain reaction which also leads to a possible reactivated Taiwanese nuclear weapon. This is presumably why he didn’t bother to raise South Korean proliferation in his reply but rather, focused in on the big power, Japan, that could present a new and independent threat center to China should it become nuclear-armed.

Why might Secretary of State Tillerson think that this threat might work? The statement has credibility in large part because of shifts in Japan’s orientation towards its nuclear option. In the last decade, Japanese leaders have shifted from no plausible proliferation pathway, combining no intention to realize nuclear weapons from its latent, inactive capacity based on its space launching rockets, vast separated plutonium stockpile, and technological base, to exploiting the latter as an active “technological deterrent” in its dealings with China, Russia, Korea, and the United States. Multiple politicians such as former minister of defense and current secretary general of the ruling LDP Party Shigeru Ishiba have explained this shift which has been noted in the region and beyond with great concern, as well as in Japan itself.[10] China will correctly perceive Japanese, not South Korean potential proliferation to be the main implicit threat in his statement.

5. The substance of the nuclear compellence threat

The Secretary of State’s statement is an example of nuclear compellence, not deterrence. That is, it attempts to use nuclear threat to compel China to do something it does not intend to do. Compellence threats are generally much harder to make successfully than deterrence threats, especially when they are ambiguous. The precise goal of Secretary of State Tillerson’s threat is unclear although he presumably pressed his point in private talks once he arrived in Beijing.

Contextually, the Chinese and third parties will conclude that it is intended to pressure China to force the DPRK to change its behavior and disarm its nuclear weapons. However, whether or not China were to achieve this outcome, this statement also now permeates all the primary conflict axes with a US threat to unleash allied nuclear weapons if China does not conform to American demands on this score, and if not resisted or rejected outright, sets a precedent for further nuclear compellence demands. Of course, the last time that the United States employed nuclear compellence against China, during the Korean War, it didn’t go well for the United States or anyone else.

Obviously, the Chinese were already acutely aware of the possibility that Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan might proliferate in the future. They hardly needed a US Secretary of State to point it out for them. The Secretary of State’s statements are new in two respects. First, it is the first occasion that then presidential candidate Trump’s campaign rhetoric on nuclear proliferation has become official parlance, in effect, reversing nearly five decades of consistent US non-proliferation policy, even before the Korea and nuclear policy reviews under the Trump Administration are complete. It is a telling indicator of the tumultuous process and essential unpredictability of American policy under Trump. Is it policy or is not? Keeping real estate or oil well developers uncertain about one’s intention may be a good business strategy. Playing a guessing game as to American policy on nuclear weapons proliferation is not a good way to deal with great powers armed with nuclear weapons.

It is important to not read too much into nor to overstate the significance of Secretary of State Tillerson’s two statements. He may have made them to try to stay abreast with President Trump who fired off a tweet about North Korea and China without his knowledge even as he landed in China. He may have been badly briefed due to lack of senior appointments in the State Department. This seems unlikely as there are strong professionals on China matters available to be consulted in Foggy Bottom and in the embassies, and he was reportedly briefed along the way in hotels even as he skipped visiting the US embassies in each capital on his trip. He may lack sufficient discipline, command of the specialized language of nuclear warfare, or insight into the game he is playing. Some or all of the above process variables may account for why he played the Japan nuclear card. And, such statements about favoring Japanese proliferation have been made before by American officials and faded away like protracted flatulence, as circumstances evolved.[11]

It is obvious that the main point of the trip was to prepare the ground for the Xi-Trump summit. He admits as much in the second interview where he says that the major policy issues will settled at that time. It may have been his awkward way of saying to the Chinese that if the North Korean nuclear issue is not dealt with, it will bring double trouble in the future. China’s leaders are already acutely aware of this reality. The problem is that starting a conversation with Chinese diplomats culminating in a meeting with President Xi Jingping with a nuclear threat in public, followed up assuredly by a private explanation of possible expanded US sanctions on Chinese firms and banks aimed at curtailing North Korean sanctions evasion, does nothing to enlighten China on new options for joint action. On average, its policy makers are far better informed about the history and multiple dimensions of the DPRK issue than their American counterparts. If recounting these obvious facts were his message to Beijing, he should have stayed home and let the Embassy professionals communicate the bad news about possible US policy shifts to their Chinese counterparts.

6. Strategic implications of the threat

Words spoken by the US Secretary of State are consequential, especially when they are repeated. Whatever the reason, it is evident that playing the Japan nuclear card was one of his talking points, repeated twice. China’s strategic calculus must now shift to anticipate, actively, the possibility in which the United States encourages ROK and Japanese nuclear weapons proliferation on China’s border, in addition to or ultimately instead of that of North Korea. Given that China has no palatable and few possible alternatives to force North Korea to stop its nuclear armament short of invading, instituting a coup d’etat or cutting off oil and food to Kim Jong Un’s regime—which would take time to take effect given the KPA’s stockpiling and leave plenty of time for DPRK escalatory moves in response, any number of which risk war in the Korean Peninsula—the Chinese will now think through and begin to prepare for the consequences of generalized nuclear proliferation in Northeast Asia, including Taiwan, should Trump enact this threat.

The US intelligence community has already prepared and issued a full range of futures (2030) in which to consider the impact of generalized nuclear proliferation in Northeast Asia. These are available from for Secretary of State Tillerson and others in the Trump Administration to contemplate.[12] The future in which a nuclear-armed North Korea is the most vigorous and therefore potentially troublesome with its nuclear threats is a b-ipolarized East Asia with two blocs, one led by China, and the other led by the United States–precisely where President Trump may heading in a self-fulfilling prophecy with his China policies. In such futures, China and other states must now prepare for the worst case–a full-scale war involving not only the existing but also possibly new nuclear weapons states. Such a war could be existentially catastrophic for the ROK, calamitous for Japan, and ruinous for the United States (in direct costs, lost trade, and the burden of assisting the reconstruction of Korea) and for China (since it would lose a minimum of 356 billion in trade revenue). Whether it would be more or less relatively damaging for China than for the United States, Russia, or Japan, and who would be left standing let alone dominant after a nuclear war starting in Korea, is anyone’s guess.

Perhaps more dangerous even than a war in Korea involving two nuclear-armed Koreas and the United States would be a Taiwanese decision to revisit its proliferation option in these circumstances. This outcome would be certain to elicit a Chinese response that could lead to a direct clash with the United States over the Chinese core interest of sovereignty, and could be the most destabilizing result of allowing the non-proliferation framework to unravel even further than it has already due to the international community’s failure to arrest North Korea’s nuclear breakout. If a war on the Korean Peninsula would be ruinous, a war over Taiwan could realistically lead to a nuclear world war.

In the short term, Secretary of State Tillerson’s nuclear proliferation threat will force China to re-evaluate the utility of having US forces in Korea to maintain strategic stability in the Peninsula on the one hand, and in the region as a whole on the other. China has long appreciated the restraining role that the United States plays with regard to Japan’s rearmament as well as in Korea, which serves as a strategic buffer. By devaluing this restraining role, Secretary of State Tillerson also reduces China’s incentive to cooperate with the United States on an array of shared strategic concerns, even at a severe cost to themselves.

Ironically, if the United States were to unleash Japanese and ROK nuclear proliferation, it would be in China’s strategic advantage to have North Korea armed to the teeth, keeping the United States constantly off balance and distracted, as well as the primary and initial target in a nuclear war. Such a situation would tend towards imbalance and “mutual probable destruction” (as John on-fat Wong phrased it in 1983[13]), at least in inter-Korean and in Korean-Japanese relations (Korea here could mean two nuclear-armed Koreas, or one nuclear-armed, re-unified Korea). Given their geographical proximity and their mutual lack of independent early warning sensor systems to match their nuclear weapons, these nuclear adversaries would have very short, almost zero decision time (ranging from a few minutes across the DMZ in either direction to ten minutes or less for an intermediate-range missile fired across the East Sea of Korea/Sea of Japan, in either direction).

For the Sino-Japanese relationship to become strategically stable, Japan would need a nuclear force in at least hundreds if not thousands of weapons—depending on the conflict scenario–including a secure submarine retaliatory capability, which would take time to create, even with their massive plutonium stocks. Albert Wohlstetter and his colleagues such as Brian Jack explained this problem in the seventies and their conclusions have been replicated ad nauseum by American and Japanese analysts. Chinese analysts refer to this stage of nuclear proliferation as the “hidden danger” period–when a state has developed and deployed actual nuclear weapons of dubious quality and without yet having deployed a survivable retaliatory force.

Admittedly there are contrary voices in the United States who argued that a stable pro-nuclear balance of power would ensue from Japanese nuclear proliferation,[14] or that the United States would remain allied and cooperative with its allies in the region should they arm themselves with nuclear weapons.[15] Until now, however, American policy makers have found that the arguments for nuclear non-proliferation outweighed those in favor of pro-proliferation.

China will not welcome such a proliferated future. They don’t need yet another nuclear-armed state on their border to worry about. But overall, it may be less to China’s strategic disadvantage than it is to that of the United States and its allies for North Korea to have nuclear weapons facing down the ROK, Japan, and the United States. After all, who loses more if the ROK is reduced to radiating rubble in a nuclear war with the DPRK? Assuming that China stays out the fray in a second Korean War, it would immediately lose a substantial fraction of its GDP. The ROK would lose almost everything. The United States would incur not only an enormous trade loss with China, Korea, and Japan, but will also have a massive reconstruction job on its hands in a reunified Korea after a nuclear war, but at a much bigger absolute and relative cost the second time around. And this assumes that the DPRK hasn’t nuked Japan or the United States itself in the course of a war which might result from the proliferation dynamic with the additional complications of massive downwind radioactive plume deposition.

7. Global non-proliferation system also on the table

Thoughtful Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans on both sides of the DMZ already know and understand these enduring realities. Japanese leaders, like those in South Korea, also know that withdrawing from the NPT and developing nuclear weapons could cause political, economic, energy security, and geopolitical upheaval, imposing a heavy cost to be paid after such a decision.[16] After all, that is the point of the global non-proliferation system. The global nuclear non-proliferation system itself, including the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, IAEA safeguards and the technology transfer control system, would be damaged, if not entirely destroyed entirely, by such events.

For all these reasons, Secretary of State Tillerson playing the nuclear compellence card was not only strategically unsound, but vacuous. The notion that the Chinese can be herded by cracking a whip or softened up in advance of the presidential summit on such a complex and important issue is absurd. US allies and friends from Tokyo to Canberra are now scratching their head wondering what comes next from the Trump Administration.

Presumably we will find out when Xi meets Trump in April whether Secretary of State Tillerson’s attempt at nuclear compellence prefigured an actual US shift away from nuclear non-proliferation to a pro-proliferation policy. Alternately, it may have been one more of many morbid symptoms of the interregnum between the end of American nuclear hegemony in East Asia and its transition into a new, ad hoc and improvised nuclear disorder—unless another institutional framework is created to manage nuclear threat and to achieve strategic stability in the region.

III. REFERENCES

[1] Peter Hayes and Chung-in Moon, “Park Chung Hee, the CIA, and the Bomb”, NAPSNet Special Reports, September 23, 2011, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/park-chung-hee-the-cia-and-the-bomb/

[2] S. Harrison, The Widening Gulf: Asian Nationalism and American Policy, Free Press, New York, 1978, pp. 284-292.

[3] See R. Edson, “Tillerson refuses to rule out nuclearization of Asian allies to keep North Korea in check,” Fox News, March 17, 2017. The lead and then the transcript of the embedded interview follow.

KOREAN DEMILITARIZED ZONE – EXCLUSIVE: Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, in an exclusive interview with Fox News, refused to rule out increased weaponization and even nuclearization of America’s East Asian allies to deter North Korean aggression.

From actual interview video: Fox anchor intro to interview:

At 1.08: “We asked him, when it comes to changing the approach to North Korea, does the United States rule out the idea that US allies, Japan and South Korea, should beef up their forces here including [Fox’s emphasis] nuclear weapons?

[Fox switch to face-face interview with Rex Tillerson at Panmunjon: at 1:21, Fox interview is Shepard Smith]

“Smith: Are you discussing, are these options on the table, nuclearization of the Peninsula as was discussed during the campaign?

RT: 1.28 Well, we are exchanging views as I did in Japan with Prime Minister Abe. This afternoon I will be exchanging views with the leadership of the Republic of Korea as well, as on, as to our views on various approaches that can be taken.

Smith: But not ruling out either of those options sir?

RT: Nothing has been taken off the table.”

End transcript from video]

[4] C. O’Brien, “True: Trump has advocated more countries getting nuclear weapons,” Politico, October 19, 2016, at:

http://www.politico.com/blogs/2016-presidential-debate-fact-check/2016/10/true-trump-has-advocated-more-countries-getting-nuclear-weapons-230042 L. Carroll, “Donald Trump wrongly tweets that he ‘never said’ more countries should have nuclear weapons,” Politico, November 14, 2016, at:

http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2016/nov/14/donald-trump/donald-trump-wrongly-tweets-he-never-said-more-cou/ G. Gerzhoy, N. Miller, Donald Trump thinks more countries should have nuclear weapons. Here’s what the research says,” Washington Post, April 6, 2016, at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/04/06/should-more-countries-have-nuclear-weapons-donald-trump-thinks-so/?utm_term=.ca7c91ca7584

[5] M. Kelly, S. Watts, “Rethinking the Security Architecture of North East Asia, VUW Law review, 14, 2010, p.287, at: http://www3.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/VUWLawRw/2010/16.

[6] M. Green, D. Stewart, “Trump and the “Trilateral Relationship” in Northeast Asia,” (transcript), Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, New York, February 15, 2017, at: http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/en_US/studio/multimedia/20170215/index.html/_view/lang=en_US

[7] E. McPike, “Transcript: Independent Journal Review’s Sit-Down Interview with Secretary of State Rex Tillerson,” Independent Journal Review, not dated but issued March 18 2017, at: http://ijr.com/2017/03/827413-transcript-independent-journal-reviews-sit-interview-secretary-state-rex-tillerson/?utm_campaign=New+Campaign&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Sailthru&utm_term=%2ASituation+Report

[8] E. McPike, “Transcript: Independent Journal Review’s Sit-Down Interview with Secretary of State Rex Tillerson,” not dated but issued March 18 2017, at: http://ijr.com/2017/03/827413-transcript-independent-journal-reviews-sit-interview-secretary-state-rex-tillerson/?utm_campaign=New+Campaign&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Sailthru&utm_term=%2ASituation+Report

[9] J. Johnson, “Amid North Korea threat, Tillerson hints that ‘circumstances could evolve’ for a Japanese nuclear arsenal,” Japan Times, March 19, 2017, at: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/03/19/national/amid-north-korea-threat-tillerson-hints-circumstances-evolve-japanese-nuclear-arsenal/?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=EBB%2003.20.2017&utm_term=Editorial%20-%20Early%20Bird%20Brief#.WM6k_lUrK00

[10] In 2011, for example, Ishiba stated in an interview that: “Ishiba as saying “We should keep nuclear fuel cycle, which is backed by enrichment and reprocessing, cycling” in order to maintain “technical deterrence.” See interview by Masakatsu Ota, Shinano Mainichi Shinbun, October 25, 2011 (in Japanese). According to Ota, “Mr. Ishiba used the expression “技術抑止” in Japanese. “技術” means “technology.” “抑止” means “deterrent.” So generally, we can interpret this expression either as “technical deterrent” or “technological deterrent” from the context how this expression “技術抑止” is used. In the case of statement by Mr. Ishiba, my impression is that he used this expression in both ways.” Personal correspondence with Masakatsu Ota, emails, October 5, 2012.

[11] Mark Fitzpatrick recounts some of these instances in M. Fitzpatrick, Asia’s Latent Nuclear Powers: Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, Adelphi Series, 55:455, 2015, pp. 113-114, at: https://www.iiss.org/en/publications/adelphi/by%20year/2015-9b13/asias-latent-nuclear-powers-7b8a

[12] In each of these seven conceivable orders in 2030, the DPRK survives, either barely as a dependent state on China, or exploiting the space created by great power dynamics. The exception is in multipolar future in which the PRC has undergone a political transformation to a democratic state, and a regional order is constructed based on a concert of liberal, democratic states. In that order, it is possible that the DPRK reforms radically which leads to peaceful reunification, or it collapses internally and falls into the ROK’s lap. Otherwise, in the other six multipolar, bipolar, and unipolar regional orders that the region could evolve into, the DPRK exists. They are:

Multipolar:

- cooperative-competitive (fluid multi-polarity, US strongest, NK exists, dependent state)

- competitive (China strongest, US offshore, disengaged, NK exists, barely, unless US cuts deal as part of balancing)

- cooperative (multiple strong states in a liberal concert, liberalized China, with or without US, NK reforms or collapses)

Bipolar:

- competitive blocs led by US and China (Asian Cold War, NK grows most)

- China-led group vs other Asia-led groups (not US, NK exists, vassal state)

- Sino-US condominium (cooperative, but distinct spheres of influence, NK exists)

Uni-polar:

- Chinese primacy excluding the US (new Middle Kingdom, NK exists, tributary state)

See Peter Hayes, “Policy Forum – “Six Party Talks and Multilateral Security Cooperation””, NAPSNet Policy Forum, June 10, 2014, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/policy-forum-six-party-talks-and-multilateral-security-cooperation/ which draws from: D. Twining, “Global Trends 2030: Pathways for Asia’s Strategic Future,” December 10, 2012 at: http://shadow.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2012/12/10/global_trends_2030_pathways_for_asia_s_strategic_future and “Global Trends 2030: Scenarios for Asia’s Strategic Future,” December 11, 2012 at: http://shadow.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2012/12/11/global_trends_2030_scenarios_for_asia_s_strategic_future

[13] Peter Hayes, ““Mutual Probable Destruction”: Nuclear Next-Use in a Nuclear-Armed East Asia?”, NAPSNet Policy Forum, May 14, 2014, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/mutual-probable-destruction-nuclear-next-use-in-a-nuclear-armed-east-asia/

[14] A good example is: R. M. Lawrence, W. R. Van Cleave, and S. E. Young, Implications of Indian and/or Japanese Nuclear Proliferation for U.S. Defense Policy Planning, Strategic Studies Center report to US Advanced Research Projects Agency, January 1974, at: https://nautilus.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/india_nuke_stanford_1974.pdf

[15] Elbridge Colby, “Choose Geopolitics Over Nonproliferation,” The National Interest, February 28, 2014, http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/choose-geopolitics-over-nonproliferation-9969?page=6.

[16] Tetsuya Endo, former vice chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission of Japan, writes, “Japan has the technology to develop nuclear weapons and, with the relevant legal revisions, Japan could actually embark on a nuclear weapons development program… However, it would require huge commitments of manpower, material and money, and it would not be so easy to change the persisting popular anti-nuclear sentiment. More importantly, a nuclear-armed Japan would face severe isolation from the international community. Given all these grave risks, it is clear that the nuclear option is surely not in the national interest of Japan and far from a realistic policy choice.” Tetsuya Endo, “How Realistic Is a Nuclear-Armed Japan?”, NAPSNet Policy Forum, August 23, 2007, at: https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/how-realistic-is-a-nuclear-armed-japan/ And, “It is difficult to find in Japan any major public leader who strongly advocates Japan’s pursuit of its own nuclear option or who questions the credibility of U.S. nuclear deterrence. Shifts in Japan’s regional security environment and strategic culture from pacifism to realism in recent years have ended the taboo on discussing publicly the hypothetical possibility that Japan might pursue a nuclear option. After North Korea’s October 2006 nuclear test, Japanese media highlighted remarks by a limited number of Japanese politicians, including Cabinet members, who argued in favor of a public discussion about Japan’s nuclear option. Others countered that such a discussion could invoke regional concerns about Japan’s nuclear intentions. Tokyo’s decision-makers are concerned that such a discussion might undermine the trust it has fostered with its neighbors since the end of World War II. These political leaders deem retaining this trust to be of greater value to Japan than developing a nuclear deterrent against North Korea.” Hajime Izumi and Katsuhisa Furukawa, “Not Going Nuclear: Japan’s Response to North Korea’s Nuclear Test”, NAPSNet Policy Forum, July 19, 2007, at: https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/not-going-nuclear-japans-response-to-north-koreas-nuclear-test/

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.