ANNA HOOD AND MONIQUE CORMIER

MARCH 1 2024

I. INTRODUCTION

Anna Hood and Monique Cormier map existing prohibitions against nuclear threats at international law and seek to explain the scope and remit of such laws. The essay explains different views and their significance about the way these international laws apply to threats to use nuclear weapons and identifies gaps in the existing legal framework.

Anna Hood is an Associate Professor at the University of Auckland Faculty of Law a.hood@auckland.ac.nz Monique Cormier is Senior Lecturer at the Monash University Faculty of Law monique.cormier@monash.edu.au

This special report was prepared for the project Reducing the Risk of Nuclear Weapon Use in Northeast Asia. The research described in this paper was co-sponsored by the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University (RECNA), the Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, and the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament (APLN), with collaboration from the Panel on Peace and Security of Northeast Asia (PSNA). Carnegie Corporation and New Land Foundation funding of the Nuclear Threat and Signalling project supported this special report.

This report is published simultaneously by RECNA-Nagasaki University here and by APLN here. This report is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here. It was first published in the Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament here. Part II is forthcoming on March 8 2024.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank the Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability for funding this project, Arianna Bacic and Maanya Kapoor for their excellent research assistance, and nine peer reviewers for their thoughtful comments.

Banner image: Judges at the International Court of Justice delivering its July 8 1996 advisory opinion on LEGALITY OF THE THREAT OR USE OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS in response to the December 15 1994 UN General Assembly resolution 49/75 K asking the Court: “Is the threat or use of nuclear weapons in any circumstance permitted under international law ?” from Court footage at 19:11 in the 1996 documentary film The People v The Bomb: Judgment at the Hague, produced by Kevin Sanders, viewable here.

III. NAPSNET SPECIAL REPORT BY ANNA HOOD AND MONIQUE CORMIER

NUCLEAR THREATS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW PART I: THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK

MARCH 1 2024

Abstract

The international legal status of threats to use nuclear weapons is uncertain. In this article, we map existing prohibitions against nuclear threats at international law and seek to explain the scope and remit of such laws. To that end, the article explores unilateral negative security assurances; prohibitions on threats to use nuclear weapons in international agreements (including the TPNW, the nuclear weapons free zone treaties and their protocols, and the 1994 Budapest Memorandum); the rules concerning threats in the jus ad bellum regime; and the rules relating to threats in the jus in bello regime. Where there is disagreement about the way these international laws apply to threats to use nuclear weapons, we explain the different views and their significance, and we identify where there are gaps in the existing legal framework. This article is the first in a two-part series on the legality of nuclear threats.

I. INTRODUCTION

I would now like to say something very important for those who may be tempted to interfere in these developments from the outside…. [T]hey must know that Russia will respond immediately, and the consequences will be such as you have never seen in your entire history.

Vladimir Putin, February 24 2022

In 2022, Russia reminded the world of the existential threat posed by nuclear weapons when it issued multiple warnings that it was willing to use its nuclear arsenal in relation to the conflict with Ukraine (Putin 2022a; 2022b). The Russian threats were the latest in a long line of nuclear-armed states threatening to deploy their most destructive weapons against other countries. Since the dawn of the nuclear age, states with nuclear weapons have threatened to use them. Some threats have been specific and tangible, such as the USSR threatening to use nuclear weapons against Britain, France and Israel during the 1956 Suez Crisis. Some have been less explicit, yet still clearly recognisable as nuclear threats, such as the more recent bluster by the United States and North Korea goading each other about the size of their respective ‘nuclear buttons’. Other threats are more general such as the tacit threat that underpins the doctrine of nuclear deterrence, or the implicit threat of increasing a nuclear weapon stockpile.

In June 2022, the first Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) adopted a declaration in which the parties expressed ‘alarm and dismay’ at Russia’s nuclear threats and stressed ‘that any use or threat of use of nuclear weapons is a violation of international law’ (UN 2022). Despite this robust assertion of the illegality of using or threatening to use nuclear weapons, the legal status of nuclear threats remains uncertain. While plenty has been written about the legality of using nuclear weapons, less has been said about the legal status of threats. This article is the first in a two-part series that seeks to set out some of the legal issues surrounding nuclear threats.

In this first piece, we attempt to map any legal prohibitions on the threat to use nuclear weapons. We seek to explain the scope and remit of such laws, and to identify where there are gaps in existing legal frameworks. Where there is disagreement about the way international laws apply to threats to use nuclear weapons, we explain the different views and their significance. The article begins in Part II by exploring promises — known as unilateral negative security assurances — that that have been made by some nuclear-armed states not to threaten to use nuclear weapons. It explains the ambit of these promises and the extent to which they are accepted as binding under international law as unilateral declarations. Part III then sets out prohibitions on threats to use nuclear weapons that can be found in various international agreements including the TPNW; the nuclear weapon free zone treaties and their protocols; and the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. Part IV then considers the regime of international law known as jus ad bellum, which governs when states can lawfully use force against one another. It engages closely with the general prohibition on threats to use force in article 2(4) of the UN Charter and discusses the different views about how this provision applies in the context of nuclear threats. Part V turns to the jus in bello regime which applies to regulate the conduct of hostilities during an armed conflict (primarily, international humanitarian law (IHL)). In this Part, we set out the debate over which rules of IHL apply to nuclear threats made between states when at war with each other. Part VI then concludes the article by consolidating our findings on the status of nuclear threats under international law. In the second article in this series, we apply the rules we clarify in this article to various nuclear threats that have been made throughout history in order to assess their legality.

Before commencing our discussion, we have a brief note on terminology. Many different terms are employed in academic literature to refer to states that have nuclear weapons. In these two articles, we use the term ‘nuclear weapon states’ to refer to the five states that are permitted to possess nuclear weapons under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom and the United States);[1] we use the term ‘nuclear weapon possessing states’ to refer to the four states outside the NPT framework that have nuclear weapons (India, Israel, North Korea and Pakistan); and we employ the term ‘nuclear-armed states’ to refer collectively to all nine states that have nuclear weapons.

II. UNILATERAL NEGATIVE SECURITY ASSURANCES

Since the development of nuclear weapons, various nuclear-armed states have made verbal and written declarations that they will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states in certain circumstances.[2] These unilateral ‘negative security assurances’ have varied in scope and comprehensiveness, and there are debates about whether they constitute legally binding commitments or mere political declarations. With respect to scope and comprehensiveness, we suggest that there is a spectrum: at one end there are states that have made comprehensive commitments; in the middle are those that have made a range of qualified commitments; and at the other end there are those states who have not made any commitments to refrain from threatening to use nuclear weapons. With respect to the whether the negative security assurances are legally binding, we argue that while some do create legal obligations, there is significant disagreement about whether others have been accompanied by the requisite intention to be binding.

A. Comprehensive Negative Security Assurances Not to Threaten to Use Nuclear Weapons

There are two states that have made comprehensive unilateral negative security assurances regarding threats to use nuclear weapons: China and Pakistan. China has repeatedly made public declarations that it will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states (China 1995; 2010). It confirmed this commitment in the lead up to the 1995 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference. At this Review Conference, the states parties to the NPT had to determine whether they would extend the life of the NPT indefinitely or for an additional period or periods.[3] Many of the non-nuclear weapon states were wary about indefinitely extending the treaty, given little progress had been made towards the nuclear disarmament obligation in Article VI of the treaty. In a bid to allay some of the non-nuclear weapon states’ concerns about the ongoing existence of nuclear weapons and to persuade them to sign off on the permanent extension of the NPT, the nuclear weapon states each issued a negative security assurance setting out various commitments in relation to their nuclear arsenals (Bunn 1997, 7; UNIDIR 2018). China’s was the most comprehensive and unqualified. It stated that:

China undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon States or nuclear-weapon-free zones at any time or under any circumstances. This commitment naturally applies to non-nuclear-weapon States parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons or non-nuclear-weapon States that have entered into any comparable internationally binding commitment not to manufacture or acquire nuclear explosive devices (1995).

Since the 1995 Review Conference, China has frequently reiterated its commitment not to threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states (China 2010).

Pakistan has long been a proponent of negative security assurances and has advocated for the creation of a legally binding multilateral treaty that contains comprehensive prohibitions on the use and threat of use of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states (Pakistan 2012). While it has not been successful in getting other nuclear-armed states on board, Pakistan has itself publicly ‘given [its] unconditional pledge not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against states not possessing nuclear weapons’ (Pakistan 2012).

B. Qualified Negative Security Assurances Not to Threaten to Use Nuclear Weapons

In the middle of the spectrum are four states that have made qualified negative security assurances not to use nuclear weapons: the United States, the United Kingdom, India and North Korea. The negative security assurance the United States made about nuclear weapons in the lead up to the 1995 Review Conference only contained a commitment not to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states in certain situations; it did not make any mention of a prohibition on nuclear threats (US 1995). However, since that time, the US government has made it clear in its Nuclear Posture Reviews that it is willing to provide a qualified assurance around nuclear threats. The 2018 and 2022 Nuclear Posture Reviews specify that the ‘United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations’ (US Department of Defense 2018, 21; 2022, 9). In 2018, this statement was accompanied by a further qualification that ‘the United States reserves the right to make any adjustment in the assurance that may be warranted by the evolution and proliferation of non-nuclear strategic attack technologies and U.S. capabilities to counter that threat’ (US Department of Defense, 2018, 21). However, after a change of government, this wording did not appear in the 2022 version.

Similarly to the United States, the UK’s 1995 negative security assurance was confined to a commitment not to use nuclear weapons in certain situations and did not contain any promise about nuclear threats. However, in a number of recent national security reviews, the United Kingdom has committed not to ‘use, or threaten to use, nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear weapon state party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons’ (HM Government 2015, 35; 2021, 77). It is notable though that it has added several qualifications to this statement. It has made clear that the assurance will not apply ‘to any state in material breach of th[eir] non-proliferation obligations’ under the NPT and that the United Kingdom also reserves the right to review the assurance if a future threat emerges in relation to weapons of mass destruction or new technologies (HM Government 2015, 35; 2021, 77).

The third state in this middle category is India. The key instance when India has indicated a willingness to commit not to threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states was when its National Security Advisory Board issued a Draft Report on Nuclear Doctrine in 1999. That Draft Report stated that India ‘will not resort to the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons against states which do not possess nuclear weapons, or are not aligned with nuclear weapons powers’ (National Security Advisory Board 1999). There are two ways that this statement is limited. First, it only applies to non-nuclear weapon states that are outside alliances with nuclear weapons powers. This means that it does not provide protection for non-nuclear weapon states in extended nuclear deterrence alliances. Second, the Draft Report was never formally adopted casting doubt on its legal significance.

The final state that has made a qualified negative security assurance not to threaten to use nuclear weapons is North Korea. Article 5(2) of its Law on DPRK’s Policy on Nuclear Forces, issued on 8 September 2022, states that ‘The DPRK shall neither threaten non-nuclear weapons states with its nuclear weapons nor use nuclear weapons against them unless they join in aggression or an attack against the DPRK in collusion with other nuclear weapons states’ (Kurata 2023).

C. States That Have Not Made Negative Security Assurance On The Threat To Use Nuclear Weapons

At the end of the spectrum are states that have not made any negative security assurances regarding nuclear weapon threats. There are three states in this category: Israel, Russia and France. Given Israel has not formally acknowledged that it possesses nuclear weapons, it is of little surprise that it has made no commitment not to threaten to use them.

Like the other nuclear weapon states, France issued a negative security assurance in the lead up to the 1995 Review Conference. But its assurance only made a qualified commitment about not using nuclear weapons; no mention was made of a promise not to threaten to use nuclear weapons (France 1995). In 2015, President Hollande reiterated France’s 1995 commitment but again refrained from promising to rule out nuclear threats against non-nuclear weapon states. In 2022, France, the United Kingdom and United States joined together to issue the ‘P3 Joint Statement on Security Assurances’ (US Department of State 2022). That document acknowledged that negative security assurances could include assurances against the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons. However, it did not go so far as to say that all three states had agreed to negative security assurances that included both the use and threat of use of nuclear weapons. Instead, the statement noted that the P3 ‘reaffirm…our existing national security assurances regarding the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons against NNWS Parties to the NPT’ (US Department of State 2022). This wording suggests that each state was only recommitting to their existing assurances which in France’s case meant only its assurance not to use nuclear weapons.

Similar to France, Russia’s unilateral negative security assurance in 1995 contained a qualified commitment not to use nuclear weapons but was silent about issuing nuclear weapon threats (1995). At other times when Russia has articulated unilateral negative security assurances, it has always restricted them to commitments to refrain from using nuclear weapons, not from making threats.

D. The Extent to Which Negative Security Assurances are Legally Binding

Whether the negative security assurances that nuclear-armed states have made are binding commitments under international law is a contested issue. Many pronouncements made by states do not constitute internationally legally binding obligations. However, both the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Law Commission (ILC) have held that when a state makes a public statement with the intention of being bound by the content of that statement, then that statement becomes what is known as a unilateral declaration and unilateral declarations are legally binding (ICJ 1974, 46; ILC 2006, 1). This is significant because it means that a state can be held accountable under international law if it breaches a unilateral declaration and other states can seek to enforce a unilateral declaration by taking the state that made it to international courts (Eckart 2012).

Unilateral declarations can be made orally or in writing (ICJ 1974, 48) and they can be addressed to the international community generally or to specific states or other entities (ILC 2006, para 6). Binding unilateral statements must be made by persons such as the head of state, head of government or minister of foreign affairs who have the authority to commit the state to international legal obligations (ILC 2006, para 4). Key to determining the legally binding nature of such declarations is whether the state intends to be bound by it. The ICJ has held that ‘the intention to be bound is to be ascertained by interpretation of the act [of making the statement]’ (ICJ 1974, 47). It has further said that ‘[w]hen States make statements by which their freedom of action is to be limited, a restrictive interpretation is called for’ (ICJ 1974, 47).

International legal opinion is split as to which negative security assurances amount to legally binding unilateral declarations. For example, evidence against the idea that the nuclear weapon states are bound by their 1995 negative security assurances is the fact that some of the states such as the United States and France actively resisted the idea that they intended to make binding declarations when they issued the assurances (Bunn 1997). What is more, one of the recommendations made at the conclusion of the 1995 Review Conference indicated that the nuclear weapon states were open to taking additional steps to assure non-nuclear weapon states of their safety including steps that would take the ‘form of an internationally legally binding instrument’ (Bunn 1997). Such a recommendation would be unnecessary if all the nuclear weapons states regarded their existing negative assurances as legally binding.

However, there is also at least some evidence that supports an argument that the 1995 assurances were legally binding. For example, the wording of the statements themselves appears fairly promissory in nature. Further, some scholars have pointed to the fact that these negative security assurances were made to encourage the non-nuclear weapon states to indefinitely extend the NPT. They have argued that a form of estoppel emerges in such a context to prevent the nuclear weapon states from denying the binding nature of their promises because the non-nuclear weapon states relied upon them to their detriment (Bunn 1997; Eckhart 2012).[4]

The 1995 negative security assurances have been discussed by both the Security Council and the ICJ but their pronouncements do not assist in ascertaining whether the assurances are binding. The Security Council passed Resolution 984 in 1995 noting with appreciation the five negative security assurances (1995, 1). However, the Resolution did not specify whether the assurances were regarded as legally binding and as the resolution itself was not a Chapter VII resolution, it was not capable of turning the assurances into binding international law. As for the ICJ, in its Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, it treated the negative security assurances somewhat ambiguously. It noted that any threat or use of nuclear weapons ‘should’ be compatible with ‘undertakings which expressly deal with nuclear weapons’ (1996). Some have interpreted this as the Court endorsing the legally binding nature of the negative security assurances (Bunn 1997, 6). However, the word ‘should’ does not necessarily denote a legal obligation and Dino Kritsiotis argues that the Court simply did not pass judgement on the legal significance of the assurances (1996, 99-100; Eckart 2012, 165). It is thus unsettled as to whether the 1995 negative assurances all amount to binding unilateral declarations.

The situation has developed somewhat in the three decades since these events unfolded. Today it is clearer that at least some negative security assurances can be interpreted as legally binding. For example, France declared in 2023 that it regarded its 1995 negative security assurance, which it subsequently endorsed in 2009 and 2016, as binding. Further, China’s negative security assurance is worded in a way that evinces an intention to be bound by its commitment, and it has been delivered consistently and decisively for decades without any suggestion that it may not amount to a legally binding obligation.

However, uncertainty continues to surround some of the other negative security assurances made by nuclear-armed states in recent times. Indeed, although Pakistan’s negative security assurance has been articulated in fairly strident terms, it is frequently followed by language that undermines the idea that it amounts to a legal commitment. For example, in 2012 Pakistan stated, ‘we have given our unconditional pledge not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against states not possessing nuclear weapons and we are ready to transform this pledge into a legally binding international instrument’. The first half of this statement strongly suggests Pakistan intends to be legally bound by its words. However, the fact that the second half of the statement states that they are prepared ‘to transform this pledge into a legally binding international instrument’ casts doubt on the idea it considers itself bound by its negative security assurance alone.

The legal status of the UK and US’s negative security assurances is also somewhat ambiguous. For many years, the United Kingdom maintained that its declaration on not using or threatening to use nuclear weapons was a political statement only, not to be interpreted as legally binding (International Security Information Service (ISIS) 2007). Recently, however, the United Kingdom has strengthened the language of its declaration, stating in 2010 that ‘[w]e are now able to give an assurance that the UK will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are party to the NPT’ (37). Similarly, in 2010 the United States declared that it was ‘now prepared to strengthen its long-standing “negative security assurance”’ not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are complying with their NPT obligations (US Department of Defence 2010, viii). This reinforcement of the assurances has been interpreted by some as evidence of an emerging intention to be bound by the statements (Eckart 2012, 166). Muddying the waters, however, is the fact that in the 2022 P3 Joint Statement on Security Assurances referenced above, the United Kingdom and United States (and France) reaffirmed their negative security assurances, but then in the next sentence juxtaposed this with a reference to their ‘legally binding obligations’ under other international agreements (US Department of State). The conspicuous difference in describing the assurances compared to the treaty commitments gives rise to doubt about their intention to be legally bound by the negative security assurances.

It is thus apparent that much remains unclear about the legal status of the various negative security assurances. While it can be argued that some of the assurances are binding, there is too much ambiguity in relation to others to conclude with any certainty that they are legally binding.

III. THE PROHIBITION ON NUCLEAR THREATS IN INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS

There are a number of international agreements that prohibit threats to use nuclear weapons. They are, however, far from universal in their membership, or in the territory that they cover. The most recent treaty to prohibit the threat of nuclear weapons is the TPNW, which entered into force in 2021. The TPNW provides in article 1(1)(d) that ‘[e]ach State Party undertakes never under any circumstance to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices’. The 69 non-nuclear weapon state parties to the TPNW are bound by this comprehensive clause, but to date, none of the nuclear-armed states have signed or ratified the TPNW. This Part therefore focuses on the extent to which nuclear weapon states are legally obligated to refrain from making nuclear threats under international agreements that they have signed. We begin by examining their commitments under nuclear weapon free zone treaties and then briefly consider the obligations of Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States under the 1994 Budapest Memorandum where they promised not to threaten to use

A. Prohibition of Threats in Nuclear Weapon Free Zone Treaties

There are five nuclear weapon free zone treaties that address the issue of nuclear threats: the Treaty of Tlatelolco, which creates a nuclear weapon free zone in Latin America and the Caribbean; the Treaty of Rarotonga, which sets up a nuclear weapon free zone in the South Pacific; the Treaty of Bangkok, which covers Southeast Asia; the Treaty of Pelindaba, which establishes a nuclear weapon free zone in Africa; and the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia. Together these treaties cover 60 per cent of states in the international community. These treaties do not explicitly prohibit their states parties from threatening to use nuclear weapons. However, they in effect prevent states parties from making nuclear threats as they prohibit parties from possessing, producing or acquiring nuclear weapons, and a state cannot make a threat to use a nuclear weapon if it does not have any.[5]

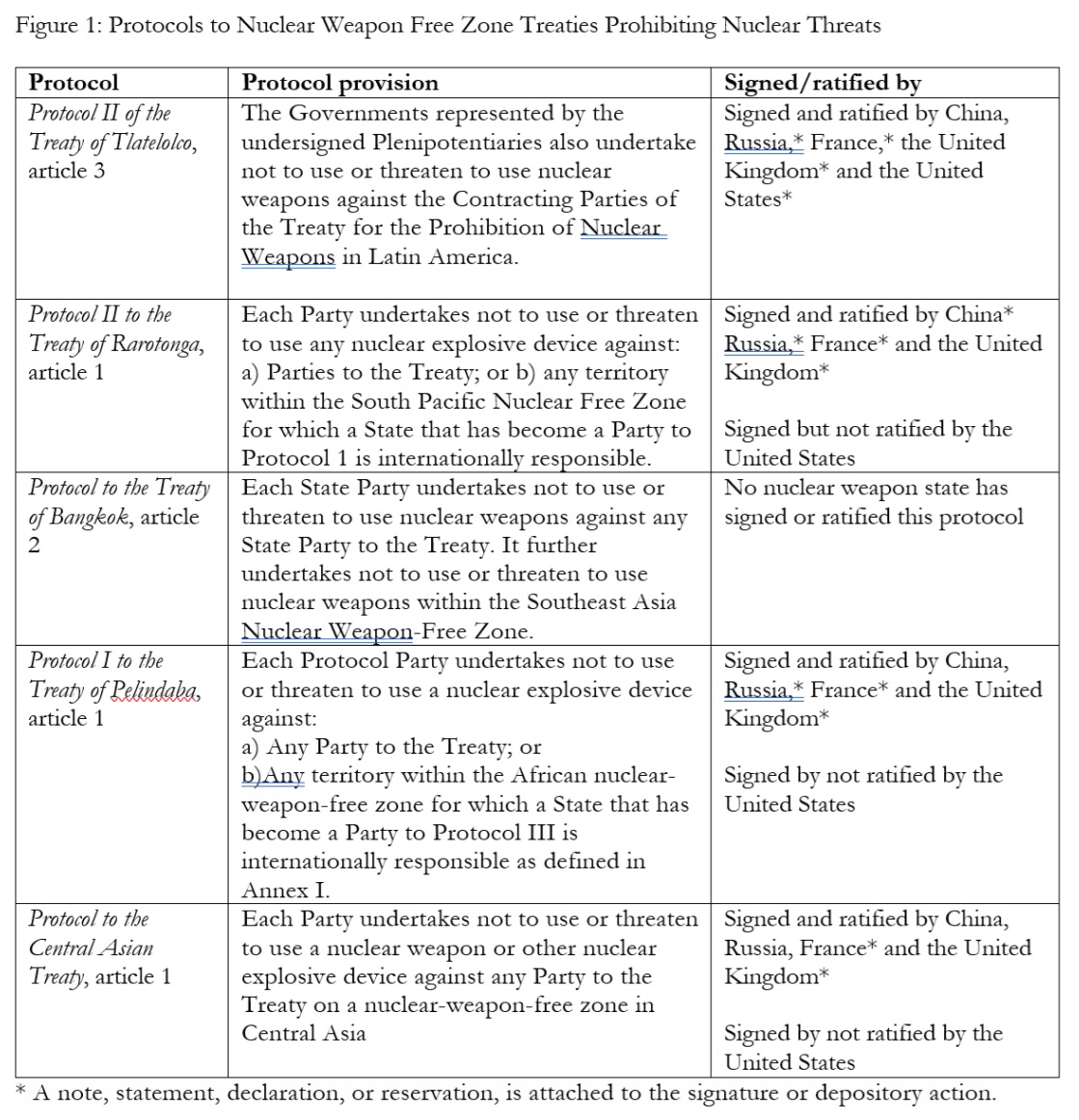

Even more significantly, each nuclear weapon free zone treaty has a protocol that the five nuclear weapon states can sign and ratify, which prohibits them from threatening to use nuclear weapons against the states parties to the treaty and in some instances from threatening to use nuclear weapons against anyone in the nuclear weapon free zone. The extent to which the nuclear weapon states have signed and ratified the protocols varies: all five nuclear weapon states have ratified Protocol II of the Treaty of Tlatelolco; no state has ratified the Protocol to the Bangkok Treaty; and China, France Russia and the United Kingdom have ratified the Protocols to the other three nuclear weapon free zone treaties while the United States has signed but not ratified them (see fig. 1).

Nuclear weapon states ratifying the relevant protocols is not, however, the end of the story. Frequently, the nuclear weapon states have made notes, statements, declarations or reservations limiting the extent of their commitment not to threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states. For example, in the protocols to the four nuclear weapon free zone treaties it has ratified, France has declared that its commitment not to threaten to use nuclear weapons does not impair its inherent right to self-defence under article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations (UN Charter) (1973; 1996a; 1996b; 2014). Further, in the protocols to the Treaty of Rarotonga, Treaty of Pelindaba and the Central Asian Treaty, it has determined that its commitment not to make nuclear threats applies only to non-nuclear weapon states that have ratified the NPT (France 1996a; 1996b; 2014).

The United Kingdom has made a number of declarations regarding its protocol commitments not to threaten to use nuclear weapons. In relation to the Protocol to the Treaty of Tlatelolco, the United Kingdom stated that it will be free to reconsider its commitment in the event that a state party to the Treaty commits an act of aggression that is supported by a nuclear weapon state (1969). In ratifying the Protocols to the Treaty of Rarotonga and Treaty of Pelindaba, the United Kingdom made it clear that it will not be bound by its commitment in the case of an invasion or attack on it, its allies or a state with which it has a security commitment, where the country carrying out the invasion or attack is in association or an alliance with a nuclear weapon state (1997; 2001). In relation to the protocols to the Treaty of Rarotonga, the Treaty of Pelindaba and the Central Asian Treaty, the United Kingdom declared that it will be released from its commitment regarding nuclear threats if a state party to the Treaties is in material breach of its non-proliferation obligations (1997; 2001; 2014). Its declaration to the Central Asian Treaty Protocol contains a further restriction which is that the United Kingdom retains the right to review its commitment if ‘the future threat, development and proliferation of [weapons of mass destruction] make it necessary’ (2014).

For the most part China has not added notes about its commitments not to threaten to use nuclear weapons. The exception was in Protocol II to the Rarotonga Treaty where it reserved ‘its right to reconsider’ its obligations under Protocol II ‘if other nuclear weapon States or the contracting parties to the Treaty take any action in gross violation of the Treaty and its attached Protocols, thus changing the status of the nuclear free zone and endangering the security interests of China’ (China 1998).

Finally, the only protocol prohibiting nuclear threats that the United States ratified is Protocol II to the Treaty of Tlatelolco. The United States did not limit this commitment in any way when it submitted the ratification document but it did note that it ‘would have to consider that an armed attack by a Contracting Party, in which it was assisted by a nuclear-weapon State, would be incompatible with the Contracting Party’s corresponding obligations under Article 1 of the Treaty’ (1971).

The table below sets out the relevant provisions in each protocol and which nuclear weapon states have signed and/or ratified them.

It is apparent from the above discussion that the nuclear weapon free zone treaties and their protocols provide some prohibitions on nuclear threats. In the event that a nuclear weapon state breached its protocol commitments by threatening to use nuclear weapons then it would have committed an internationally wrongful act and be at risk of a legal claim against it. However, it is important to appreciate that there are many holes in this web of treaties both because of instances where nuclear weapon states have failed to ratify the protocols and because of the various caveats they have added to limit their obligations. Furthermore, none of the nuclear weapon possessing states have been invited to join the protocols and so are not bound by their prohibitions on threatening to use nuclear weapons.

B. Prohibition of threats in the Budapest Memorandum

Before leaving this Part, there is one more set of international agreements worth mentioning: the memoranda that Russia, the United Kingdom and Untied States concluded with Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine at the end of the Cold War (1994a; 1994b; 1994c).[6] Although commonly referred to as the ‘Budapest Memorandum’, there were in fact three separate memoranda that each set out a number of security assurances to the former Soviet states in return for them giving up their nuclear weapons. Included in each of the memoranda was an assurance that

The Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America reaffirm their obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of [the Republic of Belarus/Kazakhstan/Ukraine], and that none of their weapons will ever be used against [the Republic of Belarus/Kazakhstan/Ukraine] except in self-defense or otherwise in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations (1994a; 1994b; 1994c).

Whether these three memoranda created legal obligations for Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States has been keenly contested.[7] Regardless of what conclusion is reached on the overall legal status of the documents, it is clear that the specific obligation to refrain from the threat of force in each memorandum was a rearticulation of the prohibition on the threat or use of force in article 2(4) of the UN Charter which is discussed in the next Part. As the relevant clauses in the Budapest memoranda did not create any additional obligations for Russia, the United Kingdom and United States beyond article 2(4), they are of minimal significance to the international legal framework for nuclear threats.

IV UN CHARTER GENERAL PROHIBITION ON THREATS (JUS AD BELLUM)

Beyond legal instruments that explicitly prohibit threats to use nuclear weapons, the UN Charter contains a general prohibition on threats to use force in international law. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter provides that ‘All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations’. This clause essentially codifies the international jus ad bellum regime that governs the limited circumstances in which a state is legally permitted to use or threaten to use force against another state. Despite its seemingly straightforward language of article 2(4), there is considerable disagreement about the scope of this provision and how it applies in the nuclear context.

This Part begins by explaining the scope of article 2(4) and the different ideas that have been expressed as to how it applies to various nuclear threats. We then consider how article 2(4) interacts with article 51 of the UN Charter which allows states to threaten to use force in self-defence before summarising our findings.

A. The Application of Article 2(4) to Threats to Use Nuclear Weapons

There are a number of different elements that make up a threat under article 2(4) of the UN Charter. While there is general agreement about what constitutes some of the elements, there are others where differing views emerge. It is widely accepted that a threat under article 2(4) is an explicit or implicit promise to use force (Roscini 2007, 235).[8] Explicit threats include threats made in writing (for example in national legislation, policy documents or communications between governments) or orally (for example, statements in the press or via speeches) (Roscini 2007, 238). Implicit threats can emerge from non-verbal sources such as a sudden build-up of weapons or troops, military demonstrations or changes to military budgets (ICJ 1986, 195; Green and Grimal 2011, 296-297). It is also accepted that threats do not have to be direct. For example, language such as ‘we will use all tools at our disposal’ can amount to threatening language (Roscini 2007, 239). In the nuclear context, we have seen a range of explicit and implicit threats over the years, some of which will be analysed in the second article in this series.

As mentioned above, article 2(4) specifies that a prohibited threat is one made ‘against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner that is inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations’. While this appears to limit the circumstances in which a threat will be recognised as contrary to the Charter, the travaux préparatoires of the UN Charter reveal that this formula was not intended to restrict what was recognised as a threat (Crawford 2019). However, even a narrow interpretation of article 2(4) would prohibit nuclear threats. This is because it is very difficult (if not impossible) to envisage how threatening to use nuclear weapons would not threaten the territorial integrity or political independence of a state. It would also undoubtedly be inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations which includes the maintenance of international peace and security, the development of friendly relations, the achievement of international cooperation and harmonisation.

To come within the bounds of article 2(4), a threat must be communicated to the threatened entity (Roscini 2007, 237). For the most part, this is uncontroversial although there may be situations involving implicit threats where further contextual information is needed.[9] For example, whether a build-up of nuclear weapons amounts to a threat or not depends on the circumstances. Additionally, there is at least one instance in history where it is uncertain whether a country succeeded in conveying its threat to use nuclear weapons to the intended target state. During the Korean War, the US Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, sent messages to Russia and India that the United States could enhance the strength of its military action and expand the area of the conflict in the hope that they would reach China. It is unclear, however, whether the messages did in fact reach China and, if they did, whether they were understood as referring to threats to employ nuclear weapons (Burr and Kimball 2022).

A further widely accepted element of an article 2(4) threat is that the threat must be credible. The bar for what constitutes a credible threat is relatively low (Jain and Seth 2019, 122; Stűrchler 2007; 259-60). There is no need to show that the threat will definitely be actioned, it is sufficient to demonstrate that it might be carried out. This is determined by having regard to the threatening state’s capability to action the threat and that state exhibiting some level of intention or commitment to do so (Hofmeister 2010, 111).

While there is broad agreement on the elements of a prohibited threat discussed so far, there are some elements where opinions differ over the precise requirements. First there is disagreement as to whether threats must be accompanied by a coercive demand requiring the threatened entity to take or not take particular action. Some scholars assume such a demand is necessary (Wood 2013; Sadurska 1988, 242). Others, however, eschew the idea that a demand is required, arguing that if one state threatens to use force against another, it is irrelevant whether the threat is accompanied by a tangible demand or not (Roscini 2007, 235; Boothby and Heintschel von Heinegg 2021, 39). Our view is that the latter approach makes the most sense. There seems little sense in forbidding threats where specific demands are attached but permitting threats that may be just as serious in nature but are not accompanied by any demands.

A further area of disagreement over the interpretation of what is required for a threat under article 2(4) is whether the threat must be specific in nature – as in directed to a named entity or entities – or whether it is possible for a threat to be general. This discrepancy is significant in the nuclear context because while many nuclear threats have been specific and targeted in nature, there are some that have been more amorphous. For example, many nuclear-armed states have policies of nuclear deterrence which contain general, untargeted threats. Indeed, the US policy of nuclear deterrence is based on the idea that it can deter ‘both large-scale and limited nuclear attacks from a range of adversaries’ by promising to retaliate if such attacks were to occur (US Department of Defense 2022, 7). This language is not targeted at any specific state but rather works as a warning to all nuclear-armed states.[10] There are a number of non-nuclear weapon states that maintain that such general deterrence doctrines are impermissible and violate the prohibition on threats in article 2(4) (Boothby and Heintschel von Heinegg 2021). However, nuclear-armed states and states under their nuclear umbrellas believe the policies are legal as do a number of international lawyers who specialise in this area (Jain and Seth 2019; Boothby and Heintschel von Heinegg 2021). The lack of consensus in this space means that it is difficult to conclude at this point in time that general policies of deterrence are currently prohibited.

The final aspect of a threat under article 2(4) is that it will only be legal if the force that is threatened would also be legal under article 2(4). This test was set down by the ICJ in its 1996 Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons. Prior to this decision there had been some discussion in the literature that some threats of unlawful force may not themselves be in violation of article 2(4) in certain circumstances (Sadurska 1988). However, today, the ICJ’s formulation of threats has been widely accepted by states, commentators, and applied by other international judicial bodies (2007; Wood 2013; Jain and Seth 2019). Under international law, the use of force is only permissible if it is authorised by the UN Security Council acting under Chapter VII of the Charter or if force is employed by a state in self-defence. To date, no state has threatened to use nuclear weapons when its use of force has otherwise been approved by the Security Council, but many threats have been made under the guise of self-defence. In light of this, the following section turns to examine the legal issues surrounding threats to use nuclear weapons in the name of self-defence.

B. Threats to Use Nuclear Weapons in the Name of Self-Defence

To determine how the prohibition on threats to use force intersects with the right to self-defence, it is first necessary to understand the scope of the right to self-defence which is set out in article 51 of the UN Charter. That clause provides that states have an ‘inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs’. It is widely agreed that this formulation of the right to self-defence has three key components. First, an armed attack must have occurred or be imminent.[11] An armed attack requires a qualitatively grave use of force to be deployed; minor military incursions are insufficient (Green and Grimal 2011, 316). Second, the use of force in self-defence must be necessary to bring the armed attack to an end or to avert an imminent attack (Jain and Seth 2019, 126-7; Wood 2013). Third, the use of force must be proportionate to the threat being faced (Jain and Seth 2019, 126-8; Wood 2013).

A threat will satisfy the first limb of the self-defence test if it is issued directly in response to an armed attack or imminent armed attack, or if the state making the threat is clear that it will only deploy its weapons in the event of a future armed attack or if it is at imminent risk of facing an armed attack in the future. There has been some confusion in the literature as to exactly how the second and third limbs of the self-defence test apply to threats. James A Green and Francis Grimal have argued that a threat to use force will be permissible if (in addition to satisfying the first limb of the test), the threat is necessary to repel the armed attack[12] and the threat is a proportionate response to the armed attack (2011, 322-5). Others, however, have suggested that the emphasis should not be on whether the threat itself satisfies the second and third limbs of article 51 but rather whether the type and amount of force threatened satisfies those requirements (Jain and Seth 2019). That is, would the envisaged use of force to be used in self-defence be necessary and proportionate.

In our view, the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons supports the second approach. The Court held that ‘[i]f the envisaged use of force is itself un-lawful, the stated readiness to use it would be a threat prohibited under Article 2, paragraph 4’ (1996, 246). It follows then that when assessing the legality of a threat in circumstances of self-defence, it needs to be considered whether the use of force envisaged by the threat would satisfy the necessity and proportionality rules of self-defence if actioned.

Applying the ICJ’s formulation, it is theoretically possible for states to threaten to use nuclear weapons where the potential use of the weapons would satisfy the criteria for self-defence. In reality, however, it is highly questionable whether threats to use nuclear weapons would be able to satisfy these criteria. In particular, there is scepticism in many quarters as to whether a nuclear weapon would ever be necessary to repel an actual or imminent armed attack and whether it could ever be used proportionately (UN 2022). Nonetheless, in its Advisory Opinion the ICJ left open the possibility that in an extreme case of self-defence, in which the very survival of a state was at stake, nuclear weapons could potentially be used lawfully in self-defence (1996, 246). In these limited circumstances, a threat to use nuclear weapons would also be lawful.

C. A Summary of When Nuclear Threats may be Legal under Article 2(4)

In concluding this Part, it is apparent that a threat to use nuclear weapons will be illegal under the UN Charter when there is:

- An explicit or implicit promise to use nuclear weapons; and

- That promise has been communicated to a specific entity being threatened; and

- The threat to use nuclear weapons is credible.

Such a threat will be legal, however, if:

- The envisaged use of nuclear weapons would only be actioned:

- With the support of the UN Security Council; or

- In the event that:

- the state making the threat had suffered an armed attack or was facing an imminent armed attack or had made it clear that it will only deploy its weapons in the event of a future armed attack or if it is at imminent risk of facing an armed attack in the future; and

- the use of nuclear weapons threatened satisfied the necessity and proportionality tests required for self-defence.

V NUCLEAR THREATS UNDER THE LAWS OF ARMED CONFLICT (JUS IN BELLO)

The final area of international law that is relevant for nuclear threats is IHL which sets out the rules in relation to means and methods of warfare that apply during armed conflict. This body of international law is also known as jus in bello, and it is distinct from jus ad bellum discussed above in relation to article 2(4) of the UN Charter. Jus in bello is not concerned with why states are using force against one another (or whether it is lawful); the rules of IHL instead regulate the conduct of hostilities once an armed conflict is underway. There is some dispute in international legal circles as to how the rules of IHL apply to threats made during armed conflict. This Part briefly sets out the two main arguments in this space.

The first approach is the one taken by the ICJ in its 1996 Advisory Opinion. In assessing the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons, the ICJ held that the legality of whether one state’s threat to use a nuclear weapon against an adversary during an armed conflict turns on whether the envisaged use of the nuclear weapon would comply with the requirements of IHL (257). IHL is a vast body of rules, but it is sufficient here to set out three of the bedrock principles of the discipline with which threats to use nuclear weapons would have to comply. First is the principle of distinction which requires that the targets of attacks must be military in nature, not civilian (ICJ 1996, 262; UN 1977; International Committee of the Red Cross 2022). This means that any threatened use of nuclear weapons during a war would need to be focussed on military targets and not civilians. A second fundamental principle is the principle of proportionality which prohibits attacks that cause ‘incidental civilian casualties and/or damage to civilian objects that would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated’ (UN 1977, art 51(5)(b); International Committee of the Red Cross 2022). In a threat context, what this would mean under the ICJ approach is that it is not permissible to threaten to use a nuclear weapon if it would cause greater harm to civilians than is needed to achieve a military objective. A third rule of IHL prohibits parties to an armed conflict from using means of warfare that would cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering (ICJ 1996, 262; UN 1977, art 35(2)). If a nuclear attack would result in superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering, the ICJ approach would mean that a threat to use nuclear weapons in such a manner would not comply with this rule.

As with the application of the rules of self-defence to nuclear threats made in a jus ad bellum context, it is difficult to imagine situations where the threatened use of a nuclear weapon during a conflict would be acceptable under the principle of distinction, the principle of proportionality, or the prohibition on causing superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering. Indeed, the ICJ stated that ‘[i]n view of the unique characteristics of nuclear weapons…the use of such weapons in fact seems scarcely reconcilable with respect for such requirements’ (ICJ 1996, 262; UN 1977, art 35(2)). However, it went on to say that, ‘[n]evertheless, the Court considers that it does not have sufficient elements to enable it to conclude with certainty that the use of nuclear weapons would necessarily be at variance with the principles and rules of law applicable in armed conflict in any circumstance’ (ICJ 1996, 262; UN 1977, art 35(2)). It will therefore be necessary to consider each nuclear threat that is made in a conflict situation on a case-by-case basis in order to assess whether it is capable of satisfying the principles of distinction, proportionality and the prohibition on superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering.

The second approach to threats made during armed conflict is that they are not generally prohibited under IHL. Gro Nystuen is a proponent of this approach and argues that there is no legal basis in IHL for the ICJ’s conclusion that threats to use certain weapons will be unlawful during an armed conflict if the use of those weapons would also be unlawful (Nystuen 2014, 148-9). Indeed, the ICJ did not provide any reasoning to substantiate its conclusion that threats to use weapons will be unlawful if their use would violate IHL (Nystuen 2014, 157). Unacknowledged by the ICJ, however, are two rules of IHL that prohibit threats in very specific situations.[13] The first prohibits threatening an adversary that there will be no survivors (UN 1977, art 40).[14] The second is that ‘threats of violence the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population are prohibited’ (UN 1977, art 51(2)).[15] Consequently, Nystuen asserts that a threat to use nuclear weapons during an armed conflict will only be illegal if it includes a threat that there will be no survivors or it is clear that the state making the nuclear threat is doing so to spread terror amongst civilians.

Given the narrow circumstances in which IHL specifically prohibits threats, Nystuen’s critique of the ICJ’s interpretation is compelling. The ICJ’s determination that a general threat to use nuclear weapons would amount to a violation of IHL if the use would breach IHL is unsubstantiated. There does not appear to be anything in the many rules and principles of IHL that specifies, or even implies, that threats are not permitted in that context.

Nonetheless, in the three decades since the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion was issued, many commentators have uncritically accepted the ICJ’s view as the correct articulation of the law. There is very little state practice on the issue to definitely conclude one way or the other as to whether the ICJ’s formulation of the legality of threats made during armed conflict has become the accepted international position. We are thus left in a situation where the status of the law in this area is uncertain.

VI CONCLUSION

This article canvassed a range of international instruments with the aim of mapping the rules of international law applicable to threats to use nuclear weapons. Our conclusion is that these rules are piecemeal, lack universal coverage, and are subject to limitations and uncertainties. Unilateral negative security assurances, for example, contain numerous caveats and only a very small number are legally binding. While protocols to nuclear weapon free zone treaties are legally binding, their ratification by nuclear weapon states remains patchy and subject to reservations. Even the question of whether nuclear threats would fall within the self-defence exception to article 2(4) of the UN Charter requires a complex assessment of necessity and proportionality, and it is far from clear precisely which laws govern nuclear threats during armed conflicts.

Mapping out the web of laws that apply to nuclear threats and understanding their intricacies is an important step in appreciating the complicated legal status of nuclear threats. To further understand the legality of nuclear threats, it is also necessary to consider how these laws apply to threats that have been made in practice. It is to this task that we turn in the second article in this series. As will be seen, additional interpretive difficulties and uncertainties arise when we examine whether specific threats comply with the existing international legal framework.

REFERENCES

Boothby, Bill, and Wolff Heintschel von Heinegg. 2021. “Nuclear Weapons Law: Where Are We Now.” Cambridge University Press, November. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009052634.

Bunn, George. 1997. “The Legal Status of the US Negative Security Assurances to Non-Nuclear Weapon States.” The Non-Proliferation Review Spring-Summer. https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/bunn43.pdf

Burr, William, and Jeffrey Kimball. 2022. “Nuclear Threats and Alerts: Looking at the Cold War Background.” Arms Control Today, April. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2022-04/features/nuclear-threats-alerts-looking-cold-war-background?emci=81457e33-55cd-ec11-997e-281878b83d8a&emdi=63c65e5b-5acd-ec11-997e-281878b83d8a&ceid=23710637.

China. 1995. “Letter Dated 6 April 1995 from the Permanent Representative of China to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General .” https://sanctionsplatform.ohchr.org/record/9330.

China. 1998. “Ratification of Protocol 2 to the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty.” October 21, 1998. http://disarmament.un.org/treaties/t/rarotonga_p2/declarations

China. 2010. “Statement by H.E. Amb. Li Song on Nuclear Disarmament at the Tenth NPT Review Conference.” https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb_663304/zzjg_663340/jks_665232/kjfywj_665252/202208/t20220810_10738693.html.

Crawford, James. 2019. Brownlie’s Principles of Public International Law. 9th ed. S.L.: Oxford Univ Press.

Eckart, Christian. 2012. Promises of States under International Law. Hart.

Federation, Russian. 1995. “Letter Dated 6 April 1995 from the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General.” https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/176536?ln=en.

Fisher, Max. 2016. “Here’s North Korea’s Official Hydrogen Bomb Statement. It’s a Doozy.” Vox, January 6, 2016. https://www.vox.com/2016/1/6/10722202/north-korea-nuclear-statement-hydrogen.

France. 1973. “Signature of Additional Protocol II to the Treaty of Tlatelolco.” Treaties.unoda.org. July 18, 1973. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/tlateloco_p2/declarations

France. 1995. “Letter Dated 6 April 1995 from the Permanent Representative of France to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General.” April 6. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/177396?ln=en.

France. 1996a. “Signature of Protocol 2 to the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty.” Treaties.unoda.org. March 25, 1996. http://disarmament.un.org/treaties/t/rarotonga_p2/declarations

France. 1996b. “Signature of Protocol I to the Pelindaba Treaty.” April 11, 1996. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/pelindaba/declarations

France. 2014. “Signature of Protocol to the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia.” May 6, 2014. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/canwfz_protocol/declarations

France. 2015. “Speech on Nuclear Deterrence.” François Hollande. Presented at the ACDN, February 19. file:///C:/Users/peter/Downloads/President-Hollande-Speech-on-Nuclear-Deterrence-19-February_a921.pdf

France. 2023. “Negative Security Assurances.” Camille Petit. Presented at the Conference on Disarmament, February 9.

Grant, Thomas D. 2014. “The Budapest Memorandum of 5 December 1994: Political Engagement or Legal Obligation?” Polish Yearbook of International Law. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2676162

Green, James, and Francis Grimal. 2011. “The Threat of Force as an Action in Self-Defense under International Law.” Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 44 (2): 285-329.

HM Government. 2010. “Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The Strategic Defence and Security Review.” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a78da21ed915d0422065d95/strategic-defence-security-review.pdf.

HM Government. 2015. “National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 a Secure and Prosperous.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-security-strategy-and-strategic-defence-and-security-review-2015.

HM Government. 2021. “Global Britain in a Competitive Age – the Integrated Review of Security Defence Development and Foreign Policy.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy.

Hofmeister, Hannes . 2010. “Watch What You Are Saying: The UN Charter’s Prohibition on Threats to Use Force.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 11 (1). https://www.jstor.org/stable/43133806.

ICJ. 1974. “Nuclear Tests (New Zealand v. France): Judgments.” December 20, 1974. https://www.icj-cij.org/case/59/judgments.

ICJ. 1986. “Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States): Judgement” 27 June 1986. https://www.icj-cij.org/case/70/judgments

ICJ. 1996. “Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons.” https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/95/095-19960708-ADV-01-00-EN.pdf.

ICJ. 2007. Guyana v Suriname, International Law Reports 139. Permanent Court of Arbitration.

ILC. 2006. “Guiding Principles Applicable to Unilateral Declarations of States Capable of Creating Legal Obligations, with Commentaries Thereto 2006.” https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/commentaries/9_9_2006.pdf.

International Committee of the Red Cross. 2022. “The ICRC’s Legal and Policy Position on Nuclear Weapons’ .” International Review of the Red Cross, June. https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/the-icrcs-legal-and-policy-position-on-nuclear-weapons-919.

International Security Information Service (ISIS). 2007. “Memorandum from the International Security Information Service (ISIS) to Select Committee on Defence.” Www.parliament.uk. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200607/cmselect/cmdfence/225/225we09.htm.

Jain, Isha, and Bhavesh Seth. 2018. “India’s Nuclear Force Doctrine: Through the Lens of Jus Ad Bellum.” Leiden Journal of International Law 32 (01): 111–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0922156518000596.

Kim, Hyung-Jin. 2022. “North Korea Threatens to Use Nuclear Weapons during South Korea, U.S. Drills.” PBS NewsHour. November 1, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/north-korea-threatens-to-use-nuclear-weapons-during-south-korea-u-s-drills.

Kritsiotis, D. 1996. “The Fate of Nuclear Weapons After the 1996 Advisory Opinions of the World Court.” Journal of Conflict and Security Law 1 (2): 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcsl/1.2.95.

Kurata, H. 2023. “North Korea’s Supreme People’s Assembly Adopts Nuclear Use Law.” The Japan Institute of International Affairs. https://www.jiia.or.jp/en/column/2023/01/korean-peninsula-fy2022-02.html

National Security Advisory Board. 1999. “Draft Report of National Security Advisory Board on Indian Nuclear Doctrine.” Government of India: Ministry of External Affairs. https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/70efe4/pdf/.

Nystuen, Gro. 2014. Threats of Use of Nuclear Weapons and International Humanitarian Law. Edited by Gro Nystuen, Stuart Casey-Maslen, and Annie Golden Bersagel. Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107337435.

Pakistan. 2012. “Statement by Pakistan: Thematic Debate on Negative Security Assurances, Conference on Disarmament.” June 12. https://docs-library.unoda.org/Conference_on_Disarmament_(2012)/1261Pakistan.pdf.

Putin, Vladimir. 2022a. “Address by the President of the Russian Federation.” February 24. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67843.

Putin. 2022b. “Signing of Treaties on Accession of Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics and Zaporozhye and Kherson Regions to Russia.” September 30. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/69465.

Roscini, Marco. 2007. “THREATS of ARMED FORCE and CONTEMPORARY INTERNATIONAL LAW.” Netherlands International Law Review 54 (02): 229-277. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0165070x0700229x.

Russia. 1979. “Ratification of Additional Protocol II to the Treaty of Tlatelolco.” January 8, 1979. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/tlateloco_p2/declarations

Russia. 1998. “Ratification of Protocol II to the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty.” April 21, 1998. http://disarmament.un.org/treaties/t/rarotonga_p2/declarations

Russia. 2011. “Ratification of Protocol I to the Pelindaba Treaty.” April 5, 2011. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/pelindaba/declarations

Russia, Ukraine, UK, and US. 1994a. “Memorandum of Security Assurances in Connection with the Accession of the Republic of Belarus to the Treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.” December 5. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=0800000280401fbb.

Russia, Ukraine, UK, and US. 1994b. “Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with Kazakhstan’s Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with Kazakhstan’s Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons .” December 5. https://www.exportlawblog.com/docs/security_assurances.pdf.

Russia, Ukraine, UK, and US. 1994c. “Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with Ukraine’s Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.” December 5. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=0800000280401fbb.

Sadurska, Romana. 1988. “Threats of Force.” American Journal of International Law 82 (2): 239-268. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2203188.

Sajid, Islamuddin. 2023. “N.Korea Threatens to Use Nuclear Weapons If US, S.Korea Continue to Show ‘Open Hostility.’” AA. March 17, 2023. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/politics/nkorea-threatens-to-use-nuclear-weapons-if-us-skorea-continue-to-show-open-hostility/2848241.

UK. 1969. “Ratification of Additional Protocol II to the Treaty of Tlatelolco.” December 11, 1969. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/tlateloco_p2/declarations

UK. 1995. “Letter Dated 6 April 1995 from the Permanent Representative of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General.” April 6. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/Disarm%20S1995262.pdf.

UK. 1997. “Ratification of Protocol 2 to the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty.” September 19, 1997. http://disarmament.un.org/treaties/t/rarotonga_p2/declarations

UK. 2001. “Ratification of Protocol I to the Pelindaba Treaty.” March 12, 2001. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/pelindaba/declarations

UK. 2014. “Signature of Protocol to the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia.” May 6, 2014. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/canwfz_protocol/declarations

UN. 1977. “Of Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts.” June 8, 1977. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/protocol-additional-geneva-conventions-12-august-1949-and-0.

UN. 1995. “Security Assurances against the Use of Nuclear Weapons to Non-Nuclear-Weapon States That Are Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.” http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/984.

UN. 2022. Draft Vienna Declaration of the 1st Meeting of States Parties of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. https://documents.unoda.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/TPNW.MSP_.2022.CRP_.8-Draft-Declaration.pdf.

UNIDIR. 2018. “A Brief History of Multilateral Proposals on Negative Security Assurances’.” https://documents.unoda.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Subsidiary-body-4-Presentation-Renate-Dwan.pdf.

US. 1971. “Ratification of Additional Protocol II to the Treaty of Tlatelolco.” May 12, 1971. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/tlateloco_p2/declarations

US. 1995. “Letter Dated 6 April 1995 from the Chargé d’Affaires A.i. Of the Permanent Mission of the United States of America to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General’.” April 6. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/Disarm%20S1995263.pdf.

US Department of Defense. 2010. “Nuclear Posture Review Report.” https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/defenseReviews/NPR/2010_Nuclear_Posture_Review_Report.pdf.

US Department of Defense. 2018. “Nuclear Posture Review 2018.” https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF.

US Department of Defense. 2022. “2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America.” https://www.defense.gov/National-Defense-Strategy/.

US Department of State. 2022. “P3 Joint Statement on Security Assurances.” https://www.state.gov/P3-Joint-Statement-On-Security-Assurances/

Wood, Michael. 2013. “Use of Force, Prohibition of Threat.” Max Planck Encyclopedias of International Law , April. https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e428.

III. ENDNOTES

[1] Note that the nuclear weapon states’ ability to possess nuclear weapons is subject to Article VI of the NPT.

[2] There have been numerous attempts since the 1960s to get nuclear-armed states to commit to a comprehensive treaty on negative security assurances but to date these efforts have failed. Note that negative security assurances can include a commitment not to use nuclear weapons as well as, or in the alternative to, a commitment not to threaten to use nuclear weapons.

[3] The NPT was designed to be reviewed 25 years after it entered into force and for a decision at that point to be made as to whether the treaty would continue indefinitely or be extended for an additional period or periods of time (NPT, art X(2)). The 1995 Review Conference marked the 25th anniversary of the NPT.

[4] The statements can be regarded as being to the non-nuclear weapon states’ detriment because those states agreed not to push for stronger disarmament commitments from the nuclear weapon states.

[5] This fact is acknowledged in the preamble to the Central Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty: ‘Recognizing that a number of regions, including Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, South-East Asia and Africa, have created nuclear-weapon-free zones, in which the possession of nuclear weapons, their development, production, introduction and deployment as well as use or threat of use, are prohibited…’.

[6] There is also the Kazakhstan Budapest Memorandum from 5 December 1994. It has not, however, been circulated publicly.

[7] For an excellent discussion of this point see Grant (2014).

[8] Note that an implicit or explicit threat to use force entails coercion.

[9] Specific examples of this situation in the nuclear context are discussed in the second article in this series.

[10] Interestingly, Jain and Seth have argued that India’s policy of nuclear deterrence that appears general in nature can in fact be understood as specific because the context in which it operates makes it clear that it is directed at deterring a Pakistani nuclear attack (2018, 123).

[11] Some states and international lawyers have argued that self-defence can also be exercised pre-emptively in the face of remote threats but this has been widely criticised and is not accepted by a sufficient number of states to amount to settled law.

[12] Green and Grimal suggest that a ‘reasonableness’ standard should be used to assess whether it is necessary for a threat to be issued in self-defence (2011, 322-23).

[13] Note that this discussion pertains to IHL rules applicable in international armed conflicts. There are two rules about threats in non-international armed conflicts but they are not relevant to this article.

[14] This is also acknowledged to be a rule of customary international law (Nystuen 2014, 163-166).

[15] This is also acknowledged to be a rule of customary international law (Nystuen 2014, 166-168).

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent