NOBUYASU ABE

MARCH 20 2022

I. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, Nobuyasu Abe underscores the need to bridge the gap between the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons so that they can together push forward the twin goals of nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament.

Nobuyasu Abe is a former UN Under-Secretary-General for Disarmament Affairs and a Commissioner of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission. He is also a former Japanese ambassador in Vienna for the IAEA and Director-General for Arms Control and Science Affairs of the Japanese Foreign Ministry.

This paper was presented to Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) in the Asia-Pacific Workshop, December 1-4, 2020, Asia Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament and published by APLN here. It is part of an upcoming edited volume WMD in Asia Pacific: Trends and Prospects.

Acknowledgement: The workshop was funded by the Asia Research Fund (Seoul).

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

This report is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here.

Banner image: Composite of TNPW signing ceremony (left) from here with NPT review conference (right) from here and 2020 global nuclear weapons from RECNA Nagasaki University (middle) from here with Wikipedia suspension bridge from here

II. NAPSNET SPECIAL REPORT BY NOBUYASU ABE

NPT-TPNW STANDOFF: WHO CAN BREAK THIS GRIDLOCK?

MARCH 20 2022

Introduction

Having secured 50 ratifications, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) came into force on January 22, 2021. The treaty’s promoters are determined to win more ratifications, which presently stands at 59. If the treaty is adhered to by a comfortable majority of states, it will come close to establishing a legal norm in the world. Nuclear weapon-possessing states were firm in opposing the TPNW and, led by the United States (US), campaigned against the signing and ratifying of the treaty. The new Biden administration may somehow soften its stance, but in view of the fact that the US opposition to the idea of a TPNW started not under the Republican Trump administration but under the Democratic Obama administration, it is hard to predict the US attitude. Opponents argue that nuclear disarmament can only be achieved step by step and jumping to the ultimate abolition and prohibition of nuclear weapons diverts attention from the NPT (Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons) and the efforts to prevent nuclear proliferation until weapons are abolished altogether. While the strength of the NPT itself is placed in doubt, the rescheduled NPT Review Conference which, first slated for August 2021 and now for some time in 2022, threatens to become a confrontation between the NPT and TPNW camps. Efforts have to be made to bridge gaps between the two camps so that they together can move to promote nuclear disarmament and strengthen nuclear non-proliferation efforts. This paper looks at who can do so and how.

There are already some signs of softening observed in some allies of nuclear weapons states. Among the US allies, New Zealand has signed and ratified the treaty. A NATO member – the Belgian government – has started to show a positive view of the treaty. Kazakhstan, a member of the Collective Security Organization allied with Russia, has also signed and ratified the TPNW. These states have proved that even allies of nuclear weapon-possessing states can join the treaty. Having done so, they must now renounce the protection of a nuclear umbrella (in the case of Kazakhstan) or, they may have already done so (in the case of New Zealand). Two NATO members, Norway and Germany, have expressed their intention to participate in the first meeting of the States parties of the TPNW which is to be held sometime during the course of 2022.

Japan is closely following the US opposition campaign against the TPNW, but in the meantime expresses its intention to try to bridge the gap between the TPNW’s proponents and opponents. It organized a group of eminent persons to advise the ways to do this bridging. The group issued a thirteen point appeal in April 2019, including reaffirming the commitment of the unequivocal undertaking by the Nuclear Weapon States (NWS) to accomplish the total elimination of their nuclear arsenals, sustaining and preserving bilateral and multilateral nuclear arms control treaties and agreements, clarifying their nuclear policies and force postures are consistent with applicable international law, especially international humanitarian law, and realization of legally binding security assurances to non-nuclear-weapon states (NNWS).[1] But to date, this Japanese effort has not achieved any significant progress in bridging the gap. There are minority voices in Japan that it should search for ways to join the treaty, or at least sign it, or observe the conference of treaty parties.

NPT—A Treaty Facing the Risk of Increasing Irrelevance

The NPT succeeded in its initial task of preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons among potential key players at the time of its entry into force in 1970.[2] Countries with sufficient industrial capability to do so but ultimately did not obtain nuclear weapons included Canada, West Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, and Australia. Taiwan’s proliferation program was blocked, and South Africa gave up its nuclear weapons and joined the NPT. Thus, the NPT did help prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. It was helped by the establishment of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) comprehensive safeguard system to monitor the nuclear activities of those countries that pledged not to acquire nuclear weapons under the treaty. The NPT, over the years, also succeeded in enticing second tier countries such as Egypt, South Africa, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Cuba, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the DPRK, France, and China, thus bringing the total number of states parties to 187 by the turn of the century. This outcome was helped by the strong diplomatic efforts of the United States, and subsequently by the end of the Cold War. As accession to the treaty was almost universal, a near international norm against nuclear proliferation was generated.

In the last three decades, however, the NPT has started to show its limitations. Non-adherents, like India and Pakistan made their own nuclear weapons and the DPRK withdrew from the treaty to build its own nuclear weapons. Clandestine nuclear weapons programs had also been proceeding in Iraq, Libya, and South Africa. Some of these have been forcibly abandoned and some were voluntarily abandoned. During this time, the inability of the IAEA safeguards to uncover nuclear weapon programs in a timely fashion became evident.

In terms of promoting nuclear disarmament, the NPT cannot claim to be very successful. Even after fifty years of its existence, there is a long way to go to achieve the goal set out in Article VI of the treaty. As the disappointment of the NNWSs about the slow progress of nuclear disarmament intensifies, the commitment of those states to adhere to their treaty obligation is weakening. In the Middle East, the de facto possession of nuclear weapons by Israel, while it is not against international law as it is not an adherent to the NPT, gives a sense of inequality to the surrounding countries and works to weaken their adherence to the NPT obligations. The 2008 decision by the Nuclear Suppliers Group to exempt India, non-NPT adherent possessing nuclear weapons, from its export restrictions also weakened the incentives of some NPT parties to strictly observe the NPT obligations because the acceptance of nuclear non-proliferation obligation and the access to nuclear supplies and technology were considered a basic bargain underlying the NPT. Goes the refrain: ‘If you can have free access to nuclear supplies and technology even without adhering to the NPT and still get nuclear weapons, why bother to adhere to the NPT?’

For all these reasons, the NPT faces another challenge to stop further proliferation of nuclear weapons. Given these evident deficiencies of the NPT, how then might these be overcome and the credibility and authority of the NPT be restored? There are at least six major steps that must be taken to achieve this result.

1. Nuclear disarmament

In 2009 US President Barack Obama pledged in Prague to work for a world without nuclear weapons. So, one approach is to simply wait for the nuclear weapon possessing states to work among themselves to achieve a world without nuclear weapons. But, it was exactly the disappointment about the lack of progress towards nuclear disarmament that led to the adoption of the TPNW. The fact that none of the nuclear weapon possessing states has shown willingness to join the TPNW indicates that they have no intention of giving up their nuclear weapons any time soon, and, without pressure, they will remain resolute on keeping these weapons. Some non-nuclear states may join the efforts to decelerate the current nuclear modernization and buildup thereby demonstrating that there are ways to overcome obstacles to nuclear disarmament, or at least ensure that the nuclear armed states refrain from any move that complicates an already complex situation.[3]

2. Regional nuclear disarmament

In the absence of concrete progress toward global nuclear disarmament, regional approaches such as the treaty-based Nuclear Weapon-Free Zones (NWFZ) have been important and crucial. Five such zones currently exist in the world and Mongolia has also been designated with a nuclear weapon-free status. Two more zones – in the Middle East and in Northeast Asia – have been proposed.

Establishing a Middle East zone free of weapons of mass destruction, as envisaged in the resolution adopted in the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference, would address Israeli nuclear weapons and arrest new nuclear proliferation in the Middle East. Twenty five years after the adoption of the resolution, however, there has been little meaningful progress towards the realization of such a zone. Arab states try to adopt a resolution calling for Israel to adhere to the NPT and accept comprehensive IAEA safeguards, meaning Israel should abandon its nuclear weapons and prove all the nuclear activities are for peaceful purposes. Israel on its part insists that for a WMD-free zone to be achieved, regional peace and security have to be established. Practically speaking, these conditions would have to be established concurrently. Thus, both sides have to show flexibility to realize any meaningful negotiation to achieve a free zone.

In Northeast Asia, if North Korean denuclearization is to be realized, it may be in the course of establishment of a Northeast Asia NWFZ. In the joint statement of the 2018 US-DPRK presidential Singapore summit, US President Trump committed to provide security guarantees to the DPRK, and DPRK Chairman Kim Jong Un reaffirmed his unwavering commitment to complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.[4] The DPRK never agreed to unilateral denuclearization but rather, to denuclearization of the entire Korean Peninsula. For the DPRK, this phrase means that not only the DPRK abandon its nuclear weapons but the ROK also pledges not to acquire nuclear weapons and accept strict verification the same way as the DPRK may be required to. Not only that, DPRK demands that there should be no nuclear weapons stationed in American bases in the ROK, which also should be verified. President Trump also “committed to provide security guarantees to the DPRK.”[5] For the DPRK however, it is not sufficient for the US to make a political statement to provide security guarantees to the DPRK; instead the US should do so in a legally binding way backed up by deeds. It follows that if the US guarantees not to invade the DPRK, it would not need to keep its forces in the ROK. The DPRK sometimes asks for renunciation of the nuclear umbrella by not only the ROK but also Japan. It also asks for the renunciation of the US-Korea Mutual Defense Treaty and the US-Japan Security Treaty. Thus, accommodating all these North Korean demands becomes synonymous with the establishment of a Northeast Asia NWFZ in which the DPRK, ROK, and Japan become bound not to acquire nuclear weapons, nor to station any nuclear forces in return for negative security assurance by the United States, China, and Russia. Abandonment of alliances and the nuclear umbrella will be a subject of negotiations in drafting a NWFZ treaty.

3. IAEA Safeguard system

The Iraq and the DPRK cases demonstrated that existing IAEA safeguards system at the time were not effective enough to uncover the clandestine nuclear activities early enough to prevent the progress of the clandestine activities. Thus, the IAEA adopted the model additional protocol to supplement the existing safeguards so that its inspectors could verify a wider range of sites and use such methods as taking soil samples of minute radio isotopic particles. The problem is that even after more than two decades since its introduction, the additional protocol has not been ratified by key countries of concern such as Iran, Brazil, Argentina, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Pakistan, although it has been ratified by more than 130 countries. India has only ratified an additional protocol regarding limited facilities. The apparent political reluctance to conclude an additional protocol has to be overcome if the world is to resume nuclear disarmament in a serious manner.

4. Compliance and enforcement

The experience of the DPRK and Iran nuclear proliferation highlighted another critical issue regarding the NPT: how to enforce compliance with the NPT obligation to not acquire nuclear weapons? Whether the DPRK lawfully withdrew from the NPT or not, it continues to increase its nuclear warheads. If other NPT parties find that the DPRK can withdraw from the NPT, then the validity of the NPT will be seriously damaged, and other countries may use it as a way to acquire nuclear weapons when the time comes for them to face their own proliferation decisions. This is a question common to the NPT and the TPNW. The IAEA itself does not have any strong means to enforce compliance with the non-proliferation obligation undertaken by non-nuclear NPT parties. Ultimately non-compliance has to be reported to the UN Security Council (UNSC) and it is up to the Council to enforce compliance. During the agonizing debate concerning the Iranian question, however, the IAEA Board of Governors had considerable difficulty in reporting Iranian non-compliance with the IAEA safeguard requirements to the UNSC. Although the UNSC had declared nuclear and other WMD proliferation to be a matter affecting the maintenance of international peace and security, in practice, it has often had difficulty even addressing the issue of specific non-compliance. It seems that Council members, in particular permanent members, favor certain countries and resist addressing the question of their non-compliance. For the sake of credibility of the NPT and the IAEA, the UNSC must execute their responsibility properly and impartially. A way to do so, for example, would be to agree beforehand that the IAEA Director-General does not require the IAEA Board’s consent to report non-compliance, and the UNSC agrees beforehand that any issue of NPT non-compliance or violation should automatically be put on its agenda.

5. Closing the HEU/naval propulsion loophole

An issue that has surfaced over the years concerns the acquisition of Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) for naval propulsion purposes, particularly for nuclear-powered submarines. Brazil has been working on a program to develop nuclear submarines. There are arguments in Iran regarding the acquisition of nuclear submarines. The ROK is actively considering acquiring nuclear weapons. The AUKUS (Australia-United Kingdom-United States) arrangement is to help Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines. There is no provision in the NPT that prohibits the acquisition of HEU or nuclear submarines. The IAEA considers use of nuclear material for “military purposes” as for explosive purposes. Thus, transfer of HEU for naval propulsion is not considered diversion from peaceful purposes. Once HEU is placed in a submarine it is not subjected to the IAEA safeguard inspection. Thus, there is a risk of HEU use for naval propulsion to be used as a convenient loophole to justify uranium enrichment capability and to produce HEU that may be quickly converted to nuclear weapons production.

6. Question of deployment of small nuclear reactors

Further emerging issues concern the deployment of small nuclear reactors to warfronts and using nuclear propulsion for cruise missiles, drones, and other unmanned vehicles. Americans seem to be considering the deployment of small nuclear reactors to the warfront to solve power supply questions in the days when many gadgets and pieces of equipment consume an increasing amount of electricity without interruption. Similarly, small mobile nuclear power plants have been deployed by Russia and China close to frontlines or on disputed lands. Russia boasts about nuclear-powered cruise missiles, drones, and underwater vehicles that can operate for a far longer time than using conventional fuel. This generates concerns about the heightened possibility that these facilities may be involved and destroyed in military conflicts, or that attacks on the facilities could cause widespread radioactive contamination in the environment. Scattering many nuclear devices and material to so many places raises the risk of them stolen or misused by rogue elements. An attack destroying ballistic missile nuclear submarines would be so enormous that it could potentially signal the end of the world. The destruction of small nuclear reactors or small nuclear propulsion devices may become a matter of daily events and greatly increase the risk of environmental contamination, theft or misuse.

Pros and Cons of TPNW Coming into Force: Analysis

Proponents and opponents of the TPNW have articulated a number of arguments in the course of bitter debates leading up to its ratification. This section outlines the pro- and anti-positions, and then analyzes them in search of common ground between the NPT and the TPNW.

Pro-TPNW arguments

The first such argument is that, once used, nuclear weapons can cause “catastrophic consequences” that “cannot be adequately addressed, transcend national borders, pose grave implications for human survival, the environment, socioeconomic development, the global economy, food security, and the health of current and future generations,” the “risks concern the security of all humanity,” and “all States share the responsibility to prevent any use of nuclear weapons.”[6] Thus, nuclear disarmament and its legality cannot be left to nuclear weapon possessing states, but all the non-nuclear weapon states have a legitimate say on it. Moreover, the proponents adduce the following reasoning: (a) TPNW will help implement UN General Assembly resolutions calling for nuclear weapon elimination and the need for compliance with international humanitarian law; (b) TPNW will “reshape the global normative milieu: the prevailing cluster of laws (international, humanitarian, and human rights), norms, rules, practices, and discourse that shape how we think about and act in relation to nuclear weapons.”[7] Even though it does not have an instant impact on nuclear weapon abolition, the TPNW will “lessen their attractiveness and change the incentive structures for states that possess them and others that rely on extended nuclear deterrence.”[8] And (c), the ‘step-by-step disarmament’ approach advocated by the NWS has stalled. Among the goals set at the 1995, 2000, and 2010 NPT Review Conferences, the Conference on Middle East zone free of WMD has not moved forward. The Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT) negotiation has not started. Only the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) has been adopted but has not come into force even after more than twenty years since its adoption.

Anti-TPNW arguments

Contrary to these propositions, TPNW opponents argue first and foremost that the TPNW “does not address the security concerns that continue to make nuclear deterrence necessary, cannot result in the elimination of a single nuclear weapon and will not enhance any country’s security, nor international peace and security.”[9] They then present a countervailing chain of logic as follows: (a) Nuclear weapons possessing states remain committed to the obligations of Article 6 of the NPT on nuclear disarmament, but—given the realities of international security—nuclear disarmament can only be promoted in a step-by-step manner. Jumping to prohibition and elimination is impractical; (b) Until nuclear disarmament is attained, nuclear nonproliferation remains a high priority. The TPNW distracts attention from the NPT and risks weakening NPT-based non-proliferation efforts; (c) The TPNW posits that some treaty parties will join it still holding nuclear weapons and prescribes procedures to abandon them to fulfill the treaty’s basic obligation to accept the prohibition and the elimination of nuclear weapons. But, there is as yet no robust verification procedure to ascertain abandonment of nuclear warheads in the highly contentious real world, not to mention compliance and enforcement procedures.

Evaluating pro-con TPNW arguments in the NPT context

The TPNW leaves verification procedures to the meeting of States Parties to elaborate after the treaty comes into force. Article 8 paragraph 1 of the TPNW provides that the “States Parties shall…consider and…take decisions…on further measures for nuclear disarmament, including: “Measures for the verified, time bound and irreversible elimination of nuclear weapon programmes.”[10] As the nuclear weapon possessing countries stayed away from the negotiating conference for the treaty, they were not there to argue for the need for a robust verification process nor to provide expertise about it. So, in a way, the treaty opened a door for the nuclear weapon possessing states to consider the decision of a verification system, deadlines for elimination, and measures to ensure irreversibility. So far, the TPNW only requires that a state undertake comprehensive safeguards[11] while leaving the door open to committing to the additional protocol. Should the nuclear weapon possessing states ever start reducing and ultimately eliminating their nuclear weapons in accordance with their Article 6 obligation, they are likely to demand a robust verification system be established, whether this is part of the TPNW or not; and such a system may be employed at that time by states party to the TPNW if the disarming state has become a party to the TPNW. Such warhead dismantlement process may benefit from the studies done by the IPNDV (International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification).[12]

Also, the TPNW provides for setting a deadline to abandon nuclear weapons, when and if a nuclear weapon possessing state joins the treaty. The deadline is to be determined by the first meeting of States Parties to the treaty.[13] It may be recalled that nuclear disarmament proponents have long argued for “time-bound,” verifiable, and irreversible elimination of all nuclear weapons. The nuclear weapon possessing states contend, however, that it is unrealistic to set a definitive date for elimination in view of the years required to dismantle thousands of warheads and the complex and demanding verification and compliance measures that will be required. This is a fair question to which there is as yet no answer from TPNW proponents, and without clarity on the pathway and timelines, it is unclear that any state would undertake open-ended and absolute commitments to disarm.

A third critical issue is what to do in a case where a breakaway state declares it has acquired nuclear weapons when every other state has already abandoned their nuclear arsenals? The International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (ICNND) came up with a two-step approach to get around this question. The first priority is to get the nuclear weapon possessing states to reduce their holdings to the minimum level possible. Then, they will proceed to the final stage to eliminate their nuclear weapons taking care of the highly demanding final stage issues.[14] Recently, Parliamentarians for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (PNND) proposed that August 2045—the hundred year anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings—should be declared as the timeline by which nuclear weapons would be eliminated as a potent symbolic driver that leaves time to negotiate the security issues and to solve the technical issues outlined above.[15] Whereas nuclear abolitionists may complain that this timeline is too slow and poses too much cumulative risk even at low levels of the probability that nuclear war may occur; but at least it is a practical proposal that refutes the arguments of nuclear realists that it may take forever to eliminate all the nuclear weapons—that is, elimination will never be achieved.

Regional Dynamics on NPT and TPNW in Asia-Pacific

In the Asia-Pacific region there are three NPT-recognized Nuclear Weapon States (the United States, Russia, and China); two non-NPT nuclear weapon possessing states (India and Pakistan); and one NPT-defector nuclear weapon possessing state (the DPRK). None of the nine nuclear weapon possessing states has signed nor ratified the TPNW.

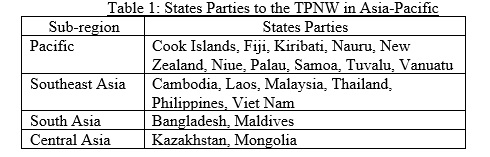

Among the remaining non-nuclear weapon possessing states, a total of twenty states have joined the TPNW as of February 19, 2021; including ten from the Pacific, six from Southeast Asia, two from South Asia and two from Central Asia. Among them New Zealand, the Philippines and Kazakhstan deserve special mention as they are in security arrangements with the United States and Russia respectively.[16]

Other states allied with a nuclear power have not joined the TPNW, viz, Japan, the ROK, and Australia allied with the United States, and Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan allied with Russia. Uzbekistan has suspended its membership in the post-Soviet Collective Security Treaty Organization.

Looking forward, Indonesia has expressed its intention to ratify the TPNW. ASEAN member states are members of the SEANWFZ (Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free-Zone) so theoretically would not have much difficulty joining the TPNW. The remaining ASEAN members are Brunei Darussalam, Myanmar, and Singapore. Likewise, the remaining member states of the Treaty of Rarotonga (South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty) would not have much difficulty joining the TPNW. The remaining states are Australia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Tonga. Among them Australia is the only state under the US nuclear umbrella. The Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau are north of the Equator and not party to the treaty but are eligible to become parties should they decide to join. The Marshall Islands has lived under the shadow of American nuclear tests and consequentially has a strong anti-nuclear sentiment. But, these states have varying degrees of political association with the United States, which may affect their decision on whether to join the TPNW.

Among the members of the Central Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone, so far, only Kazakhstan has joined the TPNW. The other members, that is, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, theoretically would not have difficulty joining the TPNW.

In contrast, Japan and the ROK, the two non-nuclear states in Northeast Asia, face considerable hurdles to joining the treaty given increasing nuclear threats from the DPRK. Additionally, Japan has an active territorial dispute with China and a potential nuclear threat from it as well as facing Russian nuclear forces located in the Russian Far East and in the coastal seas and north Pacific. Nevertheless, there is a strong internal voice in Japan supporting the TPNW. Civic groups led by mayors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have asked the government to join the treaty. Junior partner in the ruling coalition, Komeito, has asked the government to participate in the first meeting of States Parties as an observer. This domestic pressure is likely to continue.

Who Can Break the NPT-TPNW Gridlock and How?

As noted above, a number of small, middle, and large powers are committed to bridging the gap between the TPNW and the NPT, and some of them being allies of a nuclear weapon possessing state are well-placed to apply pressure in both directions. Outside the Asia-Pacific region, there are similar voices expressed in Belgium and Canada.

The first chance for the TPNW proponents and opponents to have a meeting of minds may be the next NPT Review Conference. If they are to move beyond competing for support for their respective positions, then both sides will need to reach out to those inclined to support their opponents. The NWS should show progress in nuclear disarmament efforts, or that they are determined to make some. They should show that they are working hard to decelerate nuclear arms modernization and competition, and taking measures to reduce the risk of accidental or inadvertent uses of nuclear weapons. Austria and the other proponents of the TPNW should stress that the treaty does not weaken the NPT, but rather is compatible with it and that they will be working to devise ways to achieve the abolition of nuclear weapons, for example, by strengthening the requisite disarmament verification measures and the ways to meet treaty non-compliance and the ultimate enforcement against states that might try to break out.

The next opportunity to find common ground will be at the first meeting of the TPNW States Parties when they meet in 2022. It will be an important meeting as the treaty leaves many tasks for future implementation by the States Parties. These include:

- Definition of key articles in the treaty text: What exactly, for example, is meant by Article 1 paragraph e that binds States Parties to never “a(A)ssist, encourage or induce, in any way, anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Treaty.”[17] Depending on the way this prohibition is defined, some US allies that host American military facilities, for example, ballistic missile acquisition radars or strategic communication facilities, may or may not be able to join the treaty.

- Observer status: Rules of procedure including in what manner the meeting allows non-States Parties to observe. Will states such as Japan that might attend with observers’ status be allowed to attend all the sessions of the meeting? Would they be allowed to speak? Will they be allowed to table a proposal?

- Disarmament measures and timelines: as Article 8, paragraph 1 (b) anticipates that States Parties may take additional measures for nuclear disarmament, including “[m]easures for the verified, time-bound and irreversible elimination of nuclear-weapon programmes, including additional protocols to this Treaty.”[18] The weakness of verification procedures, especially but not only from the perspective of nuclear weapon possessing states, is frequently pointed out as a major flaw in the TPNW. Efforts to elaborate robust verification procedures would help alleviate this concern. If both sides are serious enough, TPNW States Parties, NWSs, and other non-TPNW members may organize a working group to elaborate such a verification system, possibly building on the works done by the IPNDV.

There are further steps that ‘bridging countries’ may undertake to overcome the gaps between the TPNW proponents and the opponents with those who support the NPT. As noted above, dialogue sessions may be organized between them to identify ways to find common ground at the next NPT Review Conference and/or as a side event of the first meeting of the TPNW States Parties. Another approach would be to convene a conference on victim assistance and environmental remediation in parallel with the meeting of the TPNW States Parties. International cooperation to this end is envisaged in Article 6 of the treaty, and given the nature of such cooperation, willing states and civil organizations may be invited irrespective of their legal standing vis-à-vis TPNW. Article 6 seems to be modelled after the provision of the Ottawa Convention banning anti-personnel landmines. Even though the United States is not a party to the convention, it is active in demining efforts. Japan is a state that has deep expertise in the area of assisting radiation victims and environmental remediation, and domestic support for such activities, and might serve to host such a conference.

It is also critically important to remind humanity of the horrific humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons. Realistically, there is no immediate prospect that nuclear weapon possessing states will agree to abandon their nuclear weapons any time soon. Thus, it is important to ensure that the people around the world and, in particular, the political leaders and military commanders who are in the position to decide the use of nuclear weapons, are fully aware of the consequences of the use of nuclear weapons. One way to do so is to invite the people to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to observe the memorials and to talk to the surviving victims. As the victims are aging and the memories are fading, innovative methods to let the people become aware of the consequence are needed.

For the same reason, it is essential that the legal requirements under the laws of armed conflict and other pertinent international law be incorporated into every aspect of doctrinal and operational planning by nuclear weapon possessing states to prevent the manifestly illegal use of nuclear weapons and to delimit the cases as much as possible of arguably legal use until the weapons are prohibited and eliminated. All nuclear commanders and weaponeers must understand this and be ready to act on their obligation to ensure that nuclear weapons are always controlled by the criteria of discrimination, proportionality, necessity, and precaution to limit collateral damage and protect civilians from nuclear warfare.

Finally, an all-out global effort by civilian and governmental agencies is called for to support all efforts to ensure the ultimate goals of the NPT and the TPNW are realized. In particular, medical, legal, environmental, and humanitarian experts should be invited to apply their expertise in each of these activities.

III. ENDNOTES

[1] The recommendations were presented in conjunction with the NPT Review process but some of the recommendations refer to “nuclear-armed states” or “all states” such as appeal to ratify CTBT and strengthening physical protection.

[2] For the analysis of the successes and failures of the NPT refer to The NPT at Fifty: Successes and Failures by the author, published in the Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, September 2020, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/25751654.2020.1824500

[3] A formula to take care of the current deadlock about the involvement of China in the US-Russian arms control is suggested in The NPT at Fifty: Successes and Failures by the author. op. cit.

[4] Joint Statement of President Donald J. Trump of the United States of America and Chairman Kim Jong Un of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea at the Singapore Summit, June 12, 2018, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/joint-statement-president-donald-j-trump-united-states-america-chairman-kim-jong-un-democratic-peoples-republic-korea-singapore-summit/

[5] Ibid.

[6] Quotations from the TPNW preamble. July 2017, http://undocs.org/A/CONF.229/2017/8

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ramesh Thakur, “The Nuclear Ban Treaty: Recasting a Normative Framework for Disarmament.” The Washington Quarterly 40 (4), 2017, pp: 71–95, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2017.1406709

[9] Joint Press Statement from the Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the United States, United Kingdom, and France, July 7, 2017, New York City, https://usun.usmission.gov/joint-press-statement-from-the-permanent-representatives-to-the-united-nations-of-the-united-states-united-kingdom-and-france-following-the-adoption/

[10] Article 8, paragraph 1 (b) of the TPNW. Italicized emphasis added by author. https://undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/a/conf.229/2017/8

[11] Article 3, paragraph 2 of the TPNW, op. cit.

[12] Refer to https://www.ipndv.org/. On the specific issue of involving NNWS in the warhead dismantlement, refer to Carlson, John. “Verification of DPRK nuclear disarmament: the pros and cons of non-nuclear weapon states (specifically, the ROK) participating in this verification program”, NAPSNet Special Reports, May 19, 2019, and https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/verification-of-dprk-nuclear-disarmament-the-pros-and-cons-of-non-nuclear-weapon-states-specifically-the-rok-participating-in-this-verification-program/

[13] Article 4, paragraph 1, TPNW, op. cit.

[14] Section 19 of the report of the ICNND provides a set of actions to create conditions for the final elimination stage. http://www.icnnd.org/reference/reports/ent/part-iv-19.html

[15] Alyn Ware, Vanda Proskova and Saber Chowdhury, “2045: A New Rallying Call for Nuclear Abolition,” InDepth News, October 2, 2020, https://www.indepthnews.net/index.php/opinion/3934-2045-a-new-rallying-call-for-nuclear-abolition

[16] New Zealand is in the ANZUS (the relationship was once suspended but resumed in 1996), the Philippines has Mutual Defense Treaty with the United States, and Kazakhstan is in the Collective Security Organization

[17] United Nations General Assembly, Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, July 7, 2017, http://undocs.org/A/CONF.229/2017/8

[18] Ibid.

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.