North-South Korean Elements of National Power

April 27, 2011

By Peter Hayes

——————–

CONTENTS

IV. Nautilus invites your responses

I. Introduction

Peter Hayes, Executive Director of the Nautilus Institute, writes, “In this Special Report, we compare and contrast six elements that constitute national power for the ROK and the DPRK. These are: Diplomacy and international relations, Military power, Economic power, Governance and internal security, Social development, Perceptions of future prospects—internal and external to the two Koreas. This comparison demonstrates that the ROK has achieved overwhelming superiority in every dimension of national power, especially in conventional military power. “

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on contentious topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Article by Peter Hayes

-“North-South Korean Elements of National Power”

By Peter Hayes

In this Special Report, we compare and contrast six elements that constitute national power for the ROK and the DPRK. These are:

- Diplomacy and international relations.

- Military power.

- Economic power.

- Governance and internal security.

- Social development.

- Perceptions of future prospects—internal and external to the two Koreas.

This comparison demonstrates that the ROK has achieved overwhelming superiority in every dimension of national power, especially in conventional military power.

1. DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Korea was an independent kingdom with continuous administrative state control over a given territory for thousands of years, until it was occupied by Japan in1905 and subsequently annexed as a colony. Both of the modern Koreas were established as a result of the division of Korea by the United States and the former Soviet Union at the end of World War II. Both survived the Korean War with the backing of strong external support, at vast cost.

The primary driver of the diplomacy and international relations of both Koreas remains the division of the Peninsula, and the search for competitive advantage—a game that the ROK arguably won outright at the end of the Cold War when China and Russia recognized the ROK, but did not insist on a quid pro from the United States to recognize the DPRK.

Although both states are members of the United Nations and thereby bound to respect each other’s right to exist, in cultural and political reality, all Koreans know that eventually, the Korean nation and people will reunify. There is simply too much history and too many kin and social forces at work for the division to remain forever. Whether the two Korean states will reunify in the short or medium-term remains an open question, however.

A. ROK Diplomacy And International Relations

In the period from the end of the Cold War until the late seventies, the ROK’s foreign policy had two critical dimensions. The first was to cultivate its primary ally, the United States, and it undertook extraordinary (and sometimes illegal) efforts to impress and influence American decision-makers with its loyalty, including sending troops to the Vietnam War on a large scale. The second, once the rentier class was removed and an accumulating industrial class was installed by General Park Chung Hee, was to pave the way for the ROK’s burgeoning export trade, based on industries that grew out of huge Vietnam War contracts on the one hand, and massive Japanese investment on the other. In this sense, the economics of export orientation led diplomacy, and the needs of defense-led industrialization led the economic strategy in the ROK.

In the eighties, ROK President Roh Tae-woo dropped anti-communist ideology and launched his “nordpolitik,” reached out to the Soviet bloc in Europe and Asian states, often leading with a trade office or a consulate, and later with full-blown embassies. After the overthrow of the military in 1987 and the establishment of legitimate and democratic government, the ROK’s foreign policy began to diverge from a straightforward alignment on almost all issues with the United States. In the late nineties, President Kim Dae Jung put first priority on Northeast regional diplomacy, and in particular, in guiding ROK companies to make massive investments in China’s economy, to build a counter-balance to ROK dependency on Japan on the one hand, and to offset DPRK relationships with China on the other.

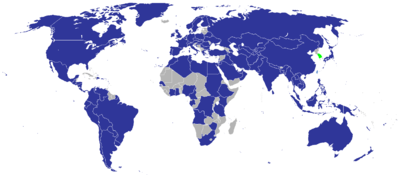

Once the ROK “graduated” from the UN list of “developing countries,” abandoned diplomatic competition with the DPRK around the world, and after becoming a UN member state in 1991, joined the OECD, it became a full-fledged diplomatic player. The acme of this achievement was the selection in 2007 of former foreign minister Ban Ki Moon to be Secretary General of the United Nations; and in 2010, its hosting of the G20 annual meeting. Trade, investment, and financing relations remain an important driver of ROK foreign policy. But the ROK now perceives itself—and is perceived to be—an important regional and global contributor to peace, security, and prosperity by virtue of its membership, funding and supply of experts who have become international civil servants in UN functional and specialized agencies, its own aid program including the OECD Development Assistance Committee (2009), its role in fielding peacekeeping forces (see map below in section 3), and even via Korean “soft power” cultural exports that create common orientations between a new generation of leaders in East Asia that are cosmopolitan, transnationally networked, and grounded in civil society.

Map of Korean diplomatic missions

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_diplomatic_missions_of_South_Korea

The ROK’s nuclear diplomacy in response to the DPRK’s nuclear proliferation activity attempted primarily to ensure that its interests were not subordinated in a US negotiations with the DPRK over the latter’s nuclear weapons program—an unenviable position for a small state to find itself, and one that lead to vacillating hot-cold stances often in opposition to the policies of its patron state. Relatedly, the ROK sought to enhance its reputation as a non-nuclear state by polishing a squeaky clean non-proliferation record, but found itself embarrassed by enrichment experiments during the nineties that transgressed its commitments with the IAEA.

B. DPRK Diplomacy and International Relations

In contrast with the ROK—one of the most diplomatically recognized countries in the world, the DPRK is one of the most isolated. Partly this arose from the alliance structure that supported the creation of the DPRK, that is, its twin dependence on the former Soviet Union and China, which became an opportunity to extract survival resources of economic and military aid when the Soviet-China relationship turned ugly in the sixties. But it also arose from the nature of the regime and its radical ideology built on the concept of self reliance and the personality cult of the great leader. For the first twenty years of competition with the ROK, a period of rebuilding from the war and of heavy industry, this strategy appeared to be working. Indeed, in the mid-sixties, the DPRK was ahead of the ROK on many economic indicators (Gerhard Breidenstein; W. Rosenberg; CIA 1975).

The DPRK focused its residual diplomatic efforts on competing with the ROK for political support, establishing embassies in non-aligned or left wing countries such as Cuba or Tanzania, or in countries of strategic significance to the DPRK, especially for arms exports (Iraq, Iran, Burma, Pakistan). Some countries were favorites due to their independent stance combined with economic value to the DPRK (India for enabling COCOM technology control evasion, Vietnam for providing rice). Some Asian leaders established close relations with the DPRK’s leadership on a personal basis (Indonesia, Cambodia) although the DPRK’s willingness to conduct diplomatic outrages (as when it bombed the Rangoon ROK embassy attempting to kill the South Korean cabinet, in 1988) ruptured these relations. By the end of the seventies, the DPRK’s outreach was utterly pragmatic and non-ideological, based purely on perceived interest, while its antiquated ideology and ossified and rigid institutions had led to a moribund economy vulnerable to withdrawal of external support (Gill 2005).

When the post-Cold War removal of Soviet era trade and external debt financing ended in 1991-almost overnight–and the Chinese began to charge full cost recovery for many items crucial to survival, the DPRK became increasingly dependent on external aid, especially food. Accordingly, it began to cultivate relations with donor countries, especially the EU, turned relations on again with Australia (then shut down the Canberra embassy due to inability to pay the rent) at the same time as it retrenched many of the primarily political outposts of Kim Il Sungist ideology and adulation. The DPRK has also cutback the presence of international agencies in Pyongyang itself over the last decade, and has provided few personnel to serve in international agencies (I know of only one, currently working for the International Federation of the Red Cross in Burma, formerly in Georgia).

A little studied but important non-state relationship for the DPRK, with significant political and economic dimensions in relation to its main current backer, China, is Taiwan.

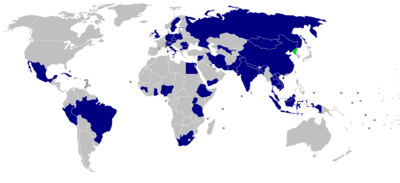

Diplomatic missions of North Korea

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_diplomatic_missions_of_North_Korea

In the nineties, the DPRK also pursued a strategy of coercive diplomacy, to substitute for its failed political and economic strategies–what Patrick Morgan (2006) calls compellence, and that I call “stalking” behaviours (Hayes, 2006b). In this regard, breaking international rules and treaty-based obligations, including pulling out of the NPT itself, and then conducting two nuclear tests, attempted to pressure on the United States to enter into dialogues on issues of concern to the DPRK. To date, its nuclear diplomacy has failed significantly in every respect, leaving the DPRK bereft of any diplomatic standing.

Overall, the DPRK’s international relations are epitomized by the fact that it has not had a note n the UN General Assembly, having lost that right due to not paying membership dues (Janes, June, 2009).

2. MILITARY POWER

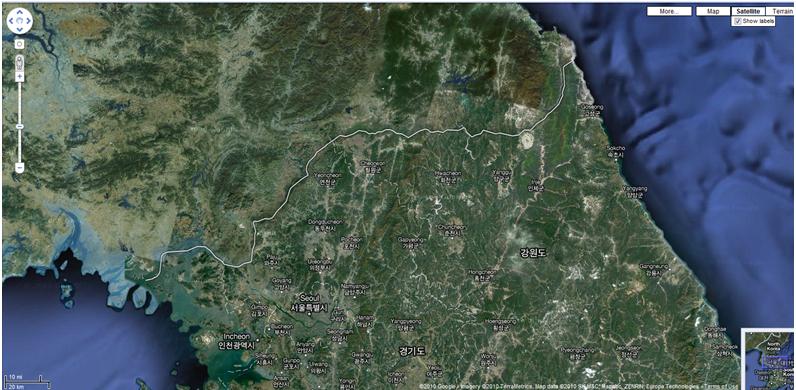

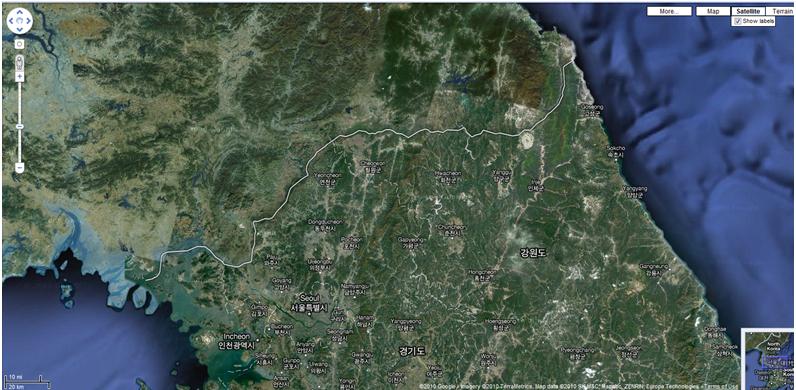

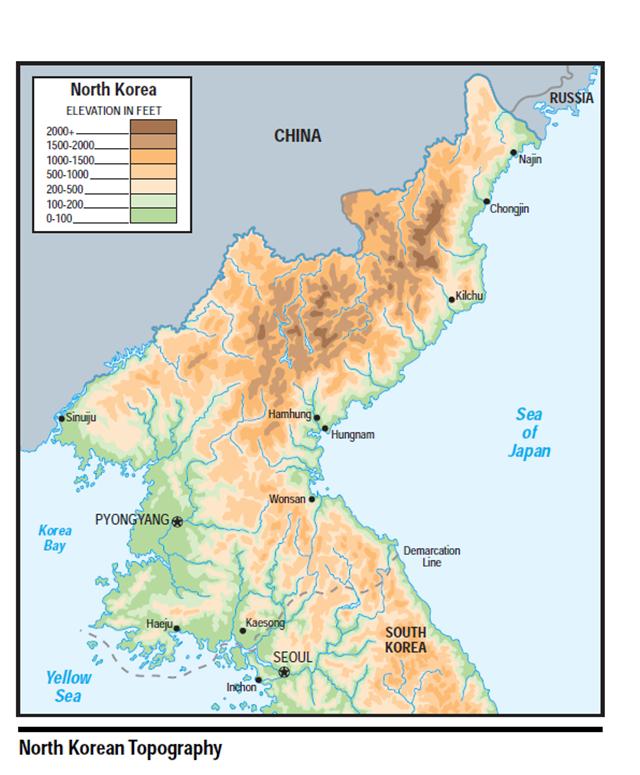

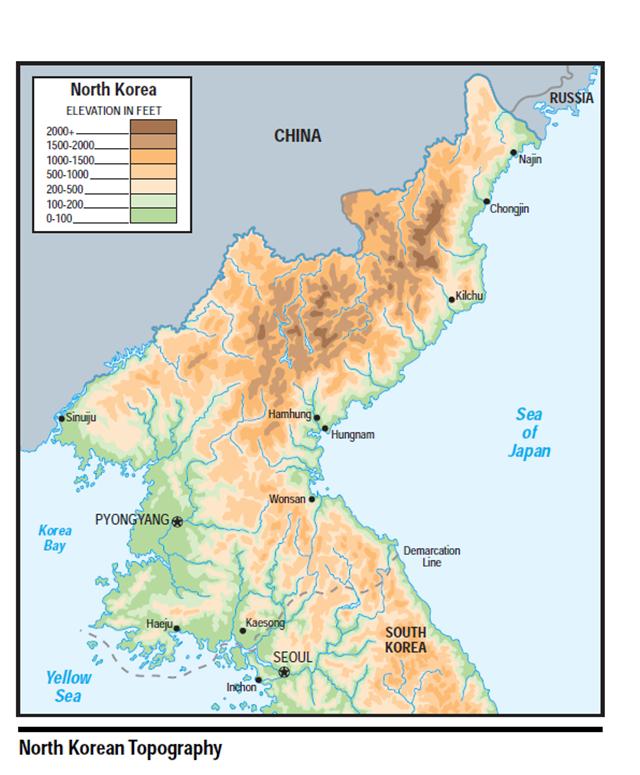

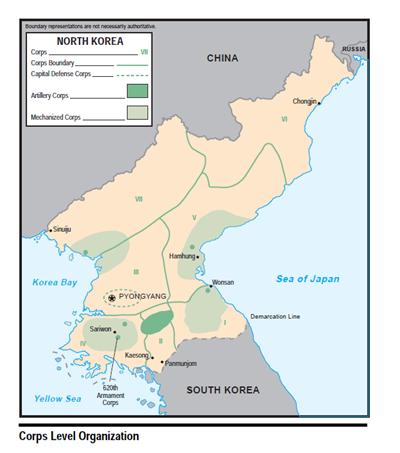

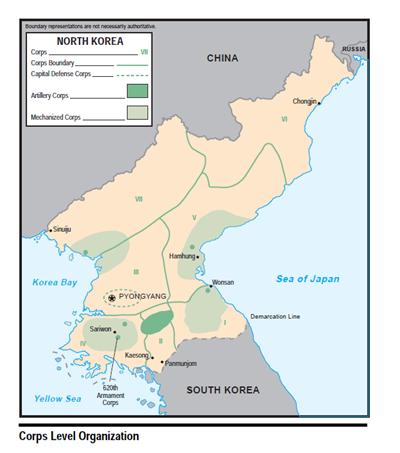

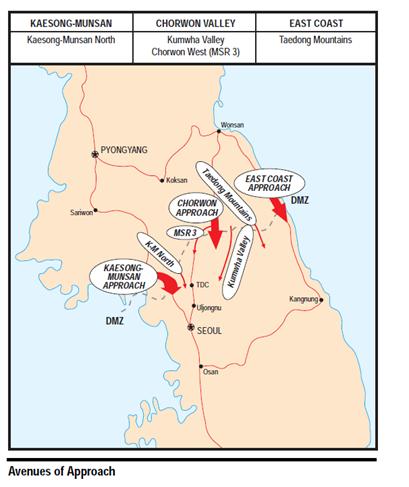

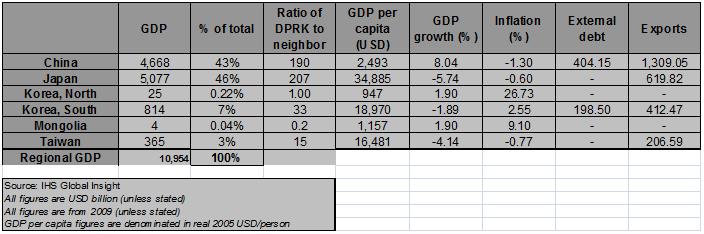

Korea is a small, mountainous country surrounded by ocean, with one land border. It is naturally well-suited to fortified defences, especially along the DMZ (see remote sensing graphic). The ocean provides external powers with direct access without overflight to deliver military forces into renewed conflict in Korea.

Source: Google Maps

Source: US Marine Corps Intelligence Activity, North Korea Country Handbook, May 1997, p. 14, released under USFOIA request to Nautilus http://www.dia.mil/publicaffairs/Foia/nkor.pdf

In summary, the DPRK has adopted a hardened, underground defense based primarily on ground infantry forces with limited mobility, ability to project power, and low stamina (less than a month at best before fuel simply runs out in wartime). The ROK by contrast has the opposite advantages, to which must be added a huge industrial surge capacity, twice the population, external allies including the United States, and a distinct but critically important psychological advantage of high morale.

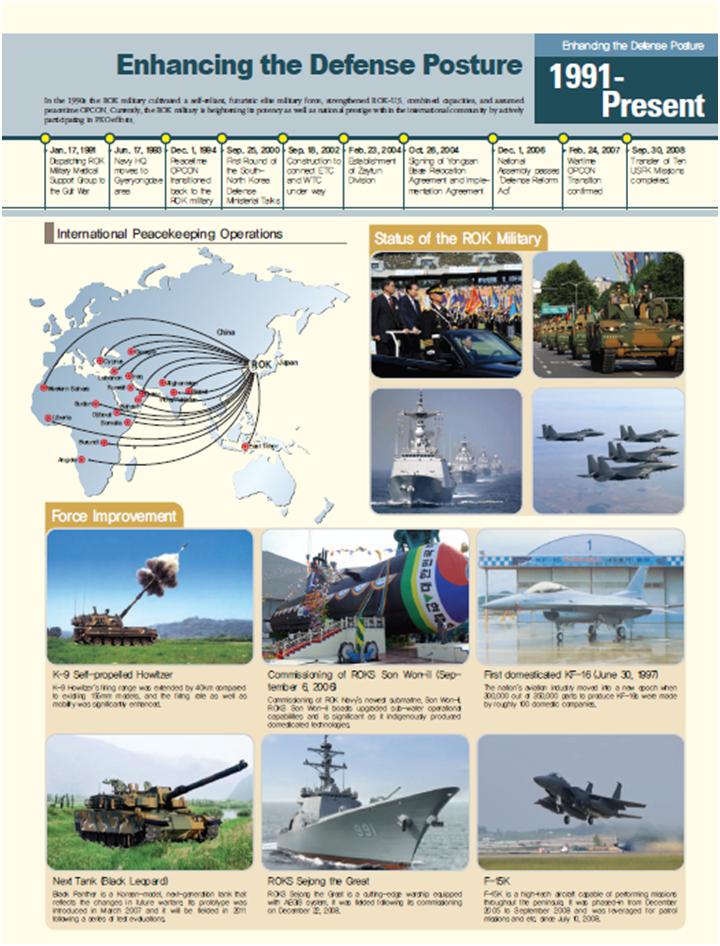

A. ROK Military Power

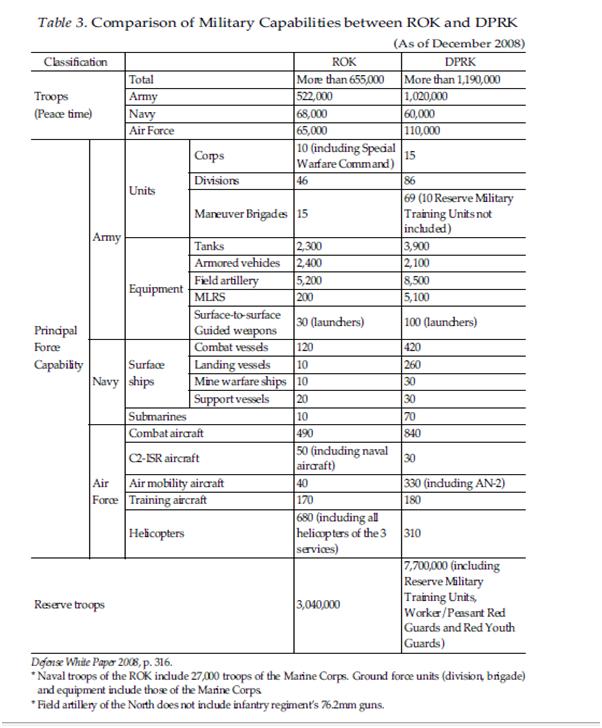

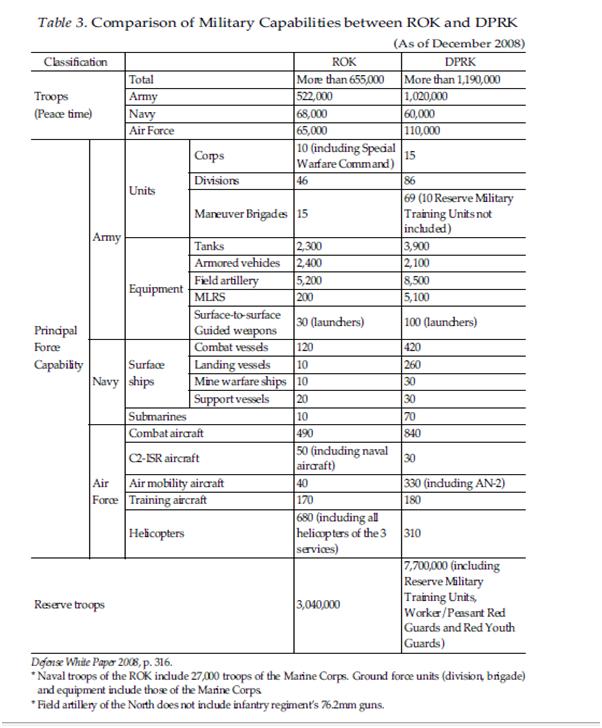

The ROK has a powerful military composed of ROK Army, Air Force, Navy and Marines. With 0.67 million active duty and 3 million reserve force soldiers, it can field three field armies. The Army is the dominant force and operates 2,300 modern tanks and nearly 700 combat helicopters (see Table of Principal Military Forces).

The Air Force has over 500 attack, fighter, and support aircraft. The Navy has over 170 ships organized into three fleets. The Marines include an amphibious support group.

The ROK spends about 2.6 percent of its GDP on defense or about $26 billion—nearly as much as the DPRK’s entire GDP. The ROK plans dramatic upgrades in military technology over the next decade to enable the armed forces to fall to half a million active and 2 million reserve personnel by 2020.

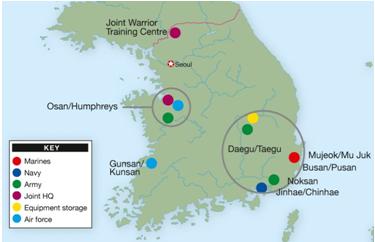

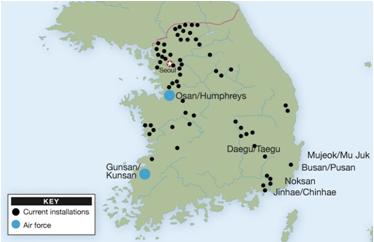

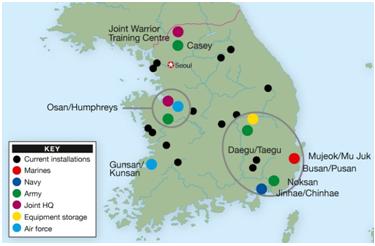

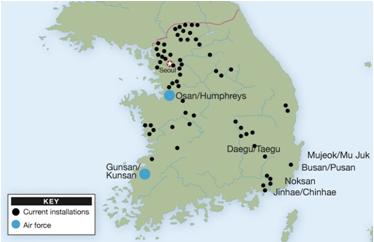

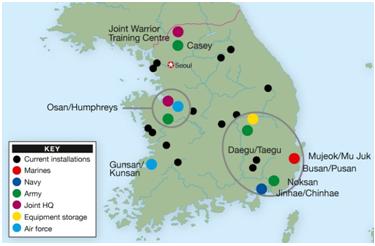

The United States also deploys about 37,500 troops in the ROK (see Table below), and a substantial fraction of Western Pacific forces in Guam, Okinawa, Hawaii, and at sea are intended for rapid mobilization and deployment to Korea in case of war. A rough estimate of the cost of US forces (in-country and in-region) dedicated to the Korea mission is $15-20 billion per year. The United States announced in 2004 that USFK troop levels would be reduced to about 28,500 but tensions in the Peninsula have stalled this shift. However, the United States military clearly intend that USFK will become primarily a regional rapidly deployable force with a residual support role for the ROK military, posing potential political dilemmas for the ROK government in the future should allied interests diverge on intervention in a conflict. As part of this shift in orientation, the United States is consolidating its bases in Korea and shifting them southward.

Left to Right: Current US facilities, 2002; middle—Phase 1 realignment that closes 35 facilities before phase 2 that leaves 2 US military hubs in the ROK (bottom). Source: Johnstone and Jones, 2010

Of greater military significance than the troops on the ground—which are a small percentage of the ROK forces—are US intelligence capacities, both local, regional and global, that provide the ROK forces with tremendous ability to monitor the DPRK forces in routine times, and to attack with lethal precision in wartime.

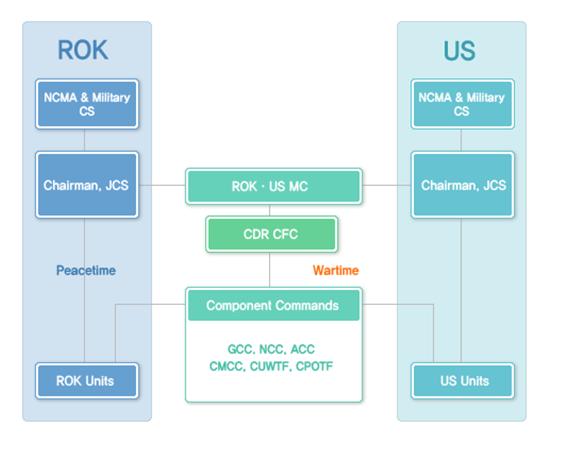

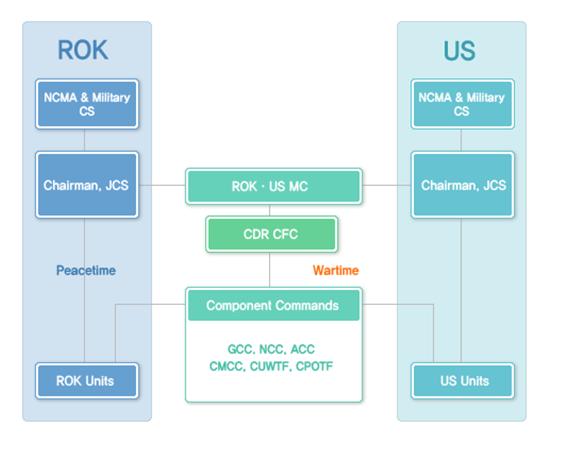

U.S. Forces, Korea / Combined Forces Command

Combined Ground Component Command (GCC)

US Forces in Korea operate under the UN flag by virtue of 1950 UNSC Resolution whereby the United States leads the United Nations Command; and under the ROK/US Mutual Security Agreement of 1954. In addition to the United States and the ROK, UN Command allies at the end of the Korea War included Australia, Belgium, Canada, Columbia, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Greece, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom. Warships from Japan were involved in support actions, but Japan was not in UNC.

The US is also partner in the ROK/US Combined Forces Command (CFC), established in 1978. The Commander of USFK also serves as Commander in Chief of the United Nations Command (CINCUNC) and the CFC. As CINCUNC, he is responsible for maintaining the 1953 armistice agreement.

US Forces, Korea (USFK) is the joint headquarters through which US combat forces would be sent to the CFC’s fighting components – the Ground, Air, Naval and Combined Marine Forces Component Commands. Major USFK Elements include the Eighth US Army, US Air Forces Korea (Seventh Air Force) and US Naval Forces Korea. USFK includes more than 85 active installations in the Republic of Korea and has about 37,500 US military personnel assigned in Korea. Major U.S. units in the ROK include the Eighth U.S. Army and Seventh Air Force.

Principal equipment in EUSA includes 140 M1A1 tanks, 170 Bradley armored vehicles, 30 155mm self-propelled howitzers, 30 MRLs as well as a wide range of surface-to-surface and surface-to-air missiles, e.g., Patriot, and 70 AH-64 helicopters.

US Air Forces Korea possesses approximately 100 aircraft: advanced fighters, e.g., 70 F-16s, 20 A-10 anti-tank attack planes, various types of intelligence-collecting and reconnaissance aircraft including U-2s, and the newest transport aircraft. With this highly modern equipment, US Air Forces Korea has sufficient capability to launch all-weather attacks and to conduct air support operations under all circumstances. In the event the Seventh Fleet and the Seventh Air Force Command augment them, the capability of USFK will substantially increase both quantitatively and qualitatively. Naval and Marine forces will be augmented in wartime.

All CFC components are tactically integrated through continuous combined and joint planning, training and exercises. In 1994, peacetime operational control (OPCON) of the ROK military was transferred from the U.S. led Combined Forces Command, to the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff. By 2005 Seoul had requested regaining wartime control of its armed forces. Final negotiations to set a date for this transition were agreed to in 2007, with a ROK military OPCON transition from CFC to the ROK JFC date set for 17 April 2012. This transfer is currently hotly debated in Korea.

Source: US Forces Korea at: http://www.usfk.mil/usfk also http://www.usfk.mil/usfk/unc.aspx and http://8tharmy.korea.army.mil/g1_AG/Programs_Policy/Publication_Records_Reg_UNC.htm http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/dod/usfk.htm

_____________________________________________________________________________

Source: http://www.mnd.go.kr/mndEng/DefensePolicy/security/combination/index.jsp

Although UN Command still exists in a formal sense, and the flags of most (but not all) allied countries still fly at Panmunjom alongside the US and ROK flags, only the United States has immediately deployable military forces committed to supporting the ROK military. Of the allies, Japan’s military force are the most immediately salient.

B. DPRK Military Power

The DPRK maintains a huge army off about 1.1 million active military personnel and about four million reserve personnel. It is difficult to translate the expenditure on these forces into a western currency but a physical estimate of DPRK military energy use is about 5-8 percent of current national energy use. Standard estimates range from $1.5-5 billion dollars equivalent which ranges for 3% to 15% of GDP estimates (depending on how the latter are measured). But there is no doubt that the DPRK is highly militarized and well-armed. Everyone in the DPRK is in the military in one way or another.

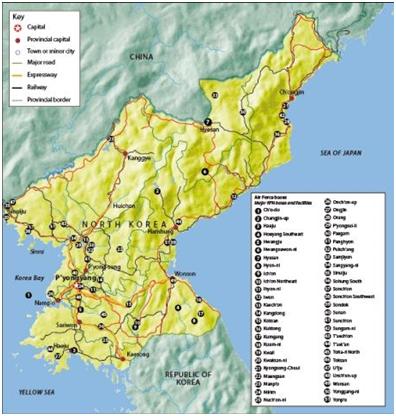

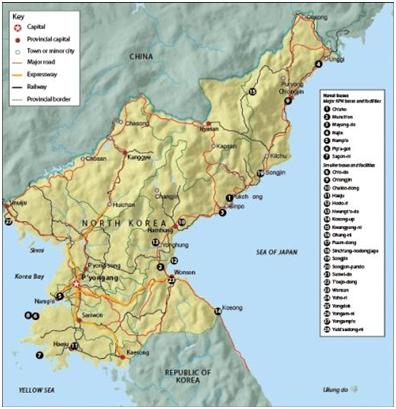

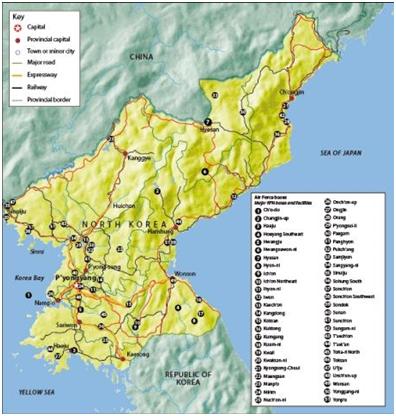

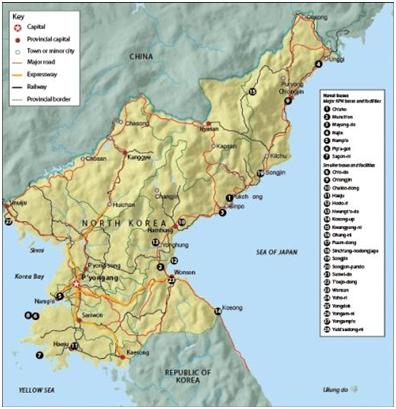

DPRK Air Bases DPRK Navy Bases

Unsurprisingly, the DPRK military is dominated by the Army, with 27 infantry divisions, 15 independent armored brigades, and a major emphasis on artillery of all types, plus about 90,000 special forces. These forces are heavily forward-deployed close to the Demilitarized Zone in order to pose a threat of attack without warning, thereby offsetting the US-ROK combined advantage in airpower, intelligence, ground force technology and mobility, training, and reinforcements by reducing the time to attack to at most a few days and possibly a few hours.

Source: Marine Corps Intelligence Activity, North Korea Country Handbook, May 1997, p. 49, released under USFOIA request to Nautilus http://www.dia.mil/publicaffairs/Foia/nkor.pdf

In response to the US-led 1991 invasion of Iraq, the KPA has adapted in several ways to high technology forces. For example, the DPRK military has developed a frequency-hopping radio for secure communications and installed fiber optic cables between facilities to protect against signals intelligence monitoring.

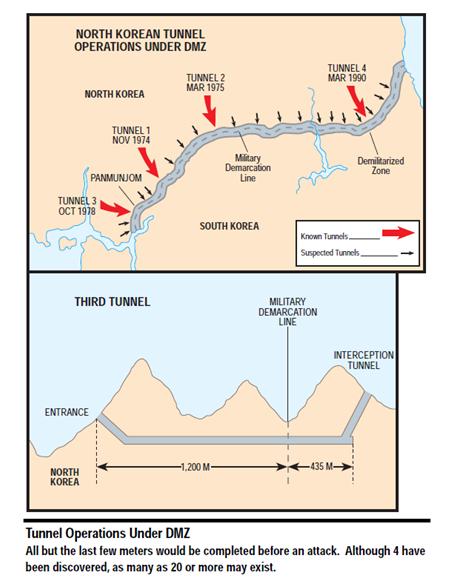

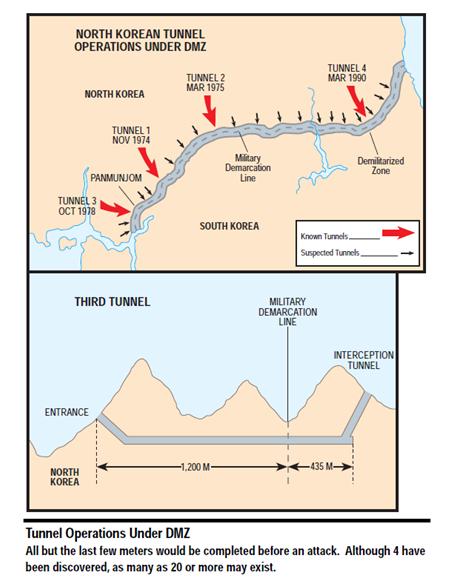

The DPRK has also constructed thousands of underground bunkers and tunnels—indeed, the whole DPRK surface settlements are epiphenomenal compared to subterranean DPRK. Given ROK and US surveillance and target acquisition capacities, it will be dangerous for forces kept underground to come out for long—and if they return underground, they are immobile and can be circumvented in counter-attacks. Thus, while very useful in a war of static position, “being underground” will be a major liability in a modern war of technology, lethal firepower, and mobility. Relatedly, the DPRK has dug tunnels under the DMZ, four of which are identified and which could enable a regiment to pass per hour—if undetected. The utility of this strategy is dubious in 2010 given modern surveillance capabilities, including thermal and seismic sensing and brings to mind the opportunity for entrapment and the military version of mid-west prairie dog hunting, including what is known colloquially as “rodenating” (using explosives to collapse burrows and killing entrapped rodents in the tunnel).

Source: Marine Corps Intelligence Activity, North Korea Country Handbook, May 1997, pp. 105-6, released under USFOIA request to Nautilus http://www.dia.mil/publicaffairs/Foia/nkor.pdf

The forward-deployed long range artillery pieces and rocket launchers within range of Seoul can inflict tremendous damage on the northern part of Seoul and on allied forces mustering near the DMZ. The DPRK reportedly has also stockpiled chemical weapons for use in the DMZ area.

In spite of its absolutely large numbers of troops and weapon systems, the DPRK military is characterized by centralized control hierarchies and obsolete or aged technology, more than half of it made in the two decades of post-war heavy industrialization. Unlike the ROK military, that experienced major combat duty in Vietnam and is deployed in many “hot” spots around the world (including northern Iraq), the DPRK military has not seen combat since 1953. Its short and medium-range missiles have a reputation for unreliability and are very inaccurate. Its long range rocket tests have all failed. Its first nuclear test in October 2006 was a dud.

Arguably, conventional parity has existed since the early 1970s. A 1994 analysis by Joint Intelligence Center-Pacific outlined static and dynamic scenarios of war developed the year before which concluded that although the DPRK could do tremendous damage, rapid reinforcement would enable the US-ROK forces to overcome the DPRK’s attack within the first two weeks, and then launch an effective counter-attack into the DPRK within a month (Hayes, 1994).

Source: Marine Corps Intelligence Activity, North Korea Country Handbook, May 1997, p. 52, released under USFOIA request to Nautilus http://www.dia.mil/publicaffairs/Foia/nkor.pdf

There are three corridors of attack for a DPRK breakthrough attempt (see Avenues of Approach graphic). In the public domain, two references provide a detailed analysis of how conventional war might unfold in Korea. The first expands on O’Hanlon’s (1998) argument that the combined advantages of terrain, force ratios, technology, communications, reconnaissance, intelligence, training, and reinforcement suggest that “… if North Korea did launch a major war, its forces would probably be so badly damaged in the initial unsuccessful assault that they might later prove incapable of posing a stalwart defense of their own territory – especially given that allied forces would have been little weakened during the initial battles.” (O’Hanlon and Mochizuki, 2003)

Indeed, the extent of US-ROK conventional force superiority may now drive a spiraling security dilemma at the DMZ because overwhelming US-ROK counter-attrition capacity over DPRK conventional forces targeting Seoul and combined forces could increase DPRK propensity to use their forces first rather than lose them (see Long 2008). Even the DPRK long range artillery and rockets may pose a lesser threat than often argued in public by US and ROK military analysts (Matsumura et al, 1998).

The 2010 International Institute of Strategic Studies review of the DPRK-ROK conventional military balance concluded: “As measured by static equipment indices, South Korea’s conventional forces would appear superior to North Korea’s. When morale, training, equipment maintenance, logistics, and reconnaissance and communications capabilities are factored in, this qualitative advantage increases. In addition, if North Korea invaded the country, South Korean forces would have the advantage of fighting from prepared defensive positions. Therefore, the Pentagon’s official current assessment of the Korean military balance suggests that, due to qualitative advantages, the South Korean–US combined force capabilities are superior to those of North Korea.”

In addition to creating a leaner and meaner military force, the Basic Plan for National Defense Reform (2009-2020) states that the ROK military will upgrade its counter-battery strike and surface-air missile defense capability against DPRK long-range artillery threatening Seoul; establish a unit dedicated to international peacekeeping duties (ROK Ministry of National Defense, 2009).

The DPRK has declared that it has weaponized its separated plutonium, which at most could provide it with up to 10 or 12 nuclear devices. Whether these are deployed nuclear devices is unknown. If so, the most likely deployment would be to pre-emplace devices in invasion corridors through which US-ROK forces might pass en route to Pyongyang, or to try to deliver a nuclear blast on allied forces massing near the DMZ to create a gap for attack, or to slow a counterattack. As Michael O’Hanlon (1998) explains, this strategy would be unlikely to work.

The DPRK’s weaponized plutonium remains more of a psychological threat device than a deployed nuclear force at this stage. In particular, the DPRK has no way to field a secure retaliatory force against the United States, which in turn extends nuclear deterrence to the ROK and Japan. Thus, the DPRK is vulnerable to pre-emptive first strike, has far less capable nuclear forces than the United States, and cannot deliver a retaliatory strike. Therefore, the DPRK nuclear force is nascent and weak, and from a purely military perspective, in many ways is a strategic liability that diverts significant command attention and forces that would be more usefully spent on conventional forces, themselves in a parlous state.

3. ECONOMIC POWER

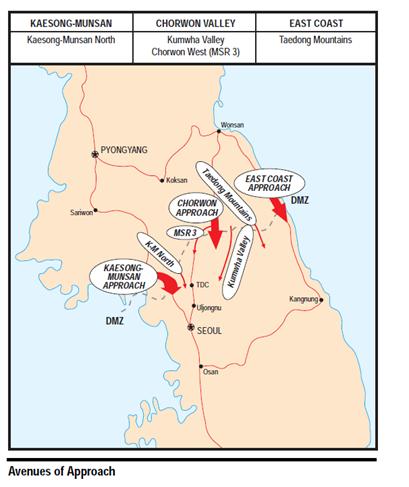

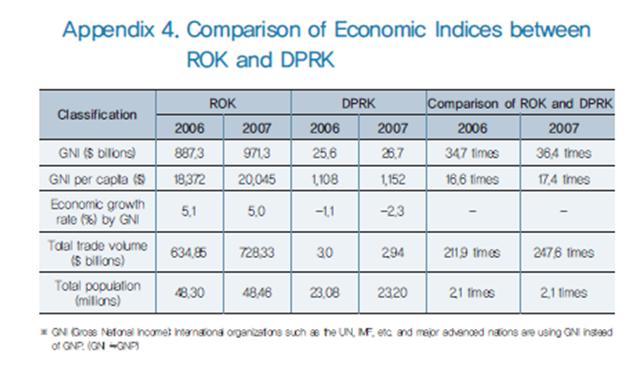

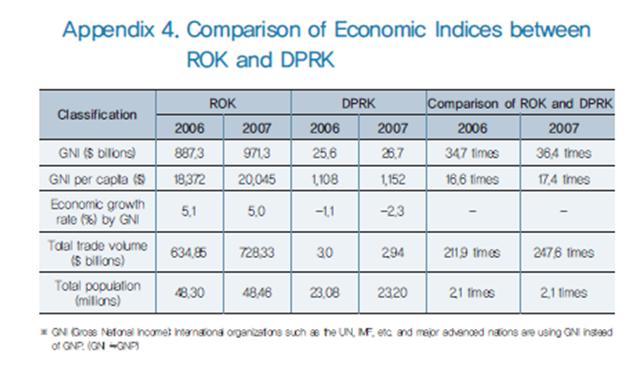

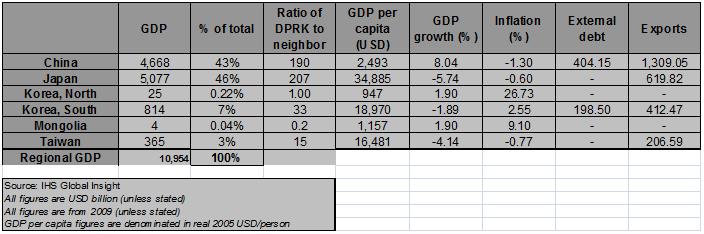

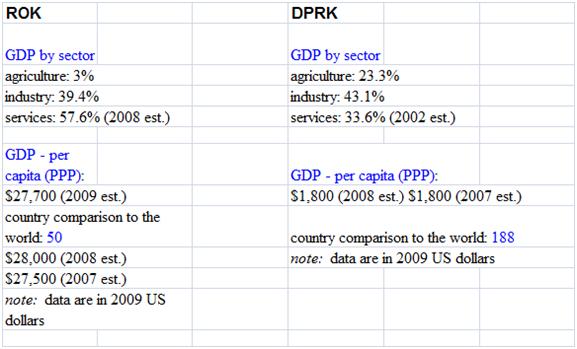

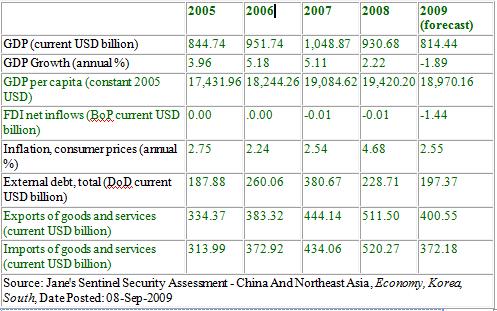

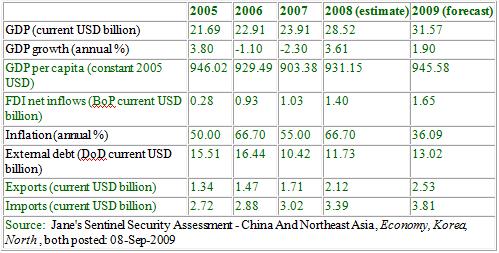

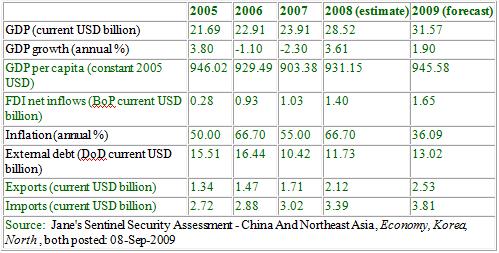

Overall, the ROK has outstripped the DPRK so far that short of a catastrophic war, it can never be overtaken in this element of national power. The basic ratios are shown below.

Source: Janes, 2010

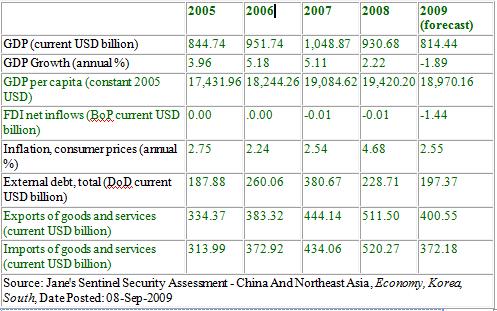

ROK Main Economic Indicators

A. ROK Economic Power

After 1965, the ROK began an accelerated growth sprint based on low wages, a highly educated and disciplined work force working incredible hours, and high rates of savings and capital investment directed into strategic sectors for export competition by authoritarian government and dirigiste policies. It rapidly left the DPRK far behind.

The 1997-98 Asian financial crisis exposed enduring weaknesses in the ROK “miracle” including high debt/equity ratios and massive short-term foreign borrowing, with a particularly weak banking sector. After plunging in 1998, GDP recovered to an annual growth rate of 9 % in 1999, passing many reforms to open the economy to greater imports and foreign investment, and favouring increased domestic consumption. Consequently, growth rates fell to 4-5 percent per year until the global economic crisis in late 2008, leading to a drop in GDP in 2009.

The ROK economy faces five major challenges. These are: demographics of aging, labor market rigidity, vulnerability to drop in demand for manufacturing exports; regulation of the oligopolistic power of the major chaebols both in creating inefficiency and in potential for corruption of the political sphere; and the threat of DPRK economic collapse and integration costs.

B. DPRK Economic Power

The DPRK’s economy is in a truly disastrous state. It is one of the most autarchic economies in the world, retaining centralized command and control planning and resource allocation, and with little opportunity to trade. Most of the DPRK’s heavy industry is degraded beyond repair and is operated only by extraordinary improvisation and with grossly inefficient use of factor inputs. The economy is also crippled by its huge military force which has first call on all resources, leaving leftovers for the line agencies responsible for the “civilian” economy. Ecological degradation due to disastrous land use planning and desperate efforts to increase food production have led to increased vulnerability to drought and flooding, creating vicious circles of reduced hydroelectric and coal production in turn reducing power generation in turn affecting rail transport and what little industry is left operating.

The government has allowed small scale service and food markets to operate in the shadows of the command economy, but regularly suppresses them in order to control corruption and to ensure that an independent economy does not emerge. Recently, it attempted currency reform which backfired severely, and forced the government to overturn the policy—a DPRK first.

The DPRK has allowed relatively small amounts of ROK investment in two zones, one at Kaesong, and one at Kumgang Mountain on the east coast. However, both of these have been buffeted by the politics of the ROK-DPRK relationship and have done little to change the DPRK’s economy.

The DPRK remains critically dependent on China for oil and food. In recent years, China has charged the DPRK prices for oil exceeding that obtained from other external oil consumers—an interesting reflection of the state of China-DPRK relations.

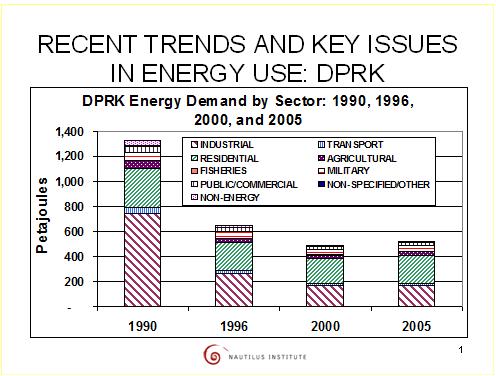

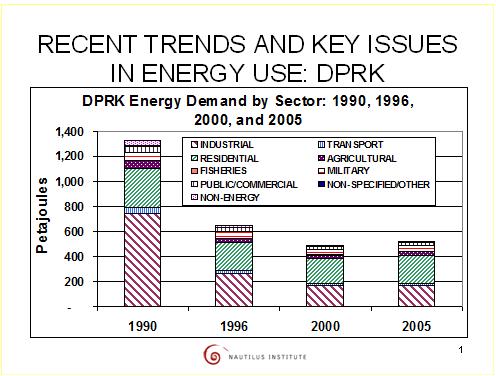

Apart from its external dependence for critically needed oil and food imports, the DPRK faces at least four major economic challenges. These are: reform of the state owned enterprises; demobilization of “excess” military personnel and conversion of military facilities; the need for shock therapy via macro-economic structural adjustment, rather than incremental and sectoral change such as occurred in China; and provision of basic physical infrastructure such as energy needed for a successful recovery or transition.

4. GOVERNANCE AND INTERNAL SECURITY

A. ROK Governance And Internal Security

As a republican-presidential political system with a weakly independent judiciary and a National Assembly with almost no policy-making powers, the ROK retains elements of authoritarian military rule as well as the extraordinary centralization of government powers in the capital city Seoul. In this respect, it could be called a “centripetal democracy.”

The current South Korean government led by President Lee Myung Bak (“Mr. 2MB”) faces strong opposition to proposed reforms in the economy and media laws from parties and political pressure groups, especially those that represent business and labor. His popularity plummeted to 21 percent in April 2008, but after a radical shift towards pragmatic, centrist policies, his support rebounded in 2009 (Moon 2010). His policies towards the DPRK, however, have been driven by conservative Christians, and have led to almost complete stasis in ROK-DPRK relations.

Social cohesion and internal security is strong in the ROK. Although economic growth has been associated with worsening social and economic inequality in the ROK, the integrative power of Korean nationalism and culture is palpable to the outsider. Given Korean propensity to collective group behaviour, political conflicts often erupt into ritualized violent confrontation.

The ROK has strong internal security forces that are independent from the ROK military. These are: the Korean National Police Agency, the Korean National Coast Guard, the Korea Customs Service, the Presidential Security Service, and the National Intelligence Service (formerly KCIA). The police field about 42,000 personnel; the other five agencies have about 11,000 personnel (Janes, Nov 16, 2009)

Overall, risk agencies such as Janes (see graphic below) put the ROK second only to Japan in “stability,” largely due to the military insecurity associated with the ROK-DPRK standoff.

B. DPRK Governance And Internal Security

The DPRK is often described as a “Communist state one-man dictatorship” (CIA, 2010) but this misrepresents the unique nature of the DPRK polity. In 1998, the DPRK official revised its constitution to make it “an independent socialist state representing the interests of all the Korean people,” which “which legally embodies Comrade Kim Il Sung ‘s Juche state construction ideology and achievements.” (DPRK 1998). This revision was amended in 2009, when Kim Jong Il was formally elevated to “Supreme Leader” and any reference to “communism” was expunged (Choe, 2009).

The pyramid of power that serves as its apex the personalized rule of Kim Jong Il has three pillars. These are the Korean Workers Party, to which all officials belong, but now greatly shrunken in effective power; the line agencies, by which the non-military economy is run; and the Korean People’s Army. Now that the line agencies have withered along with the economy, the real reinforcing rods of Kim’s rule are the military, a fact reflected in the “military first” policy he announced in 2003 that formally replaced the working class as the vanguard of the DPRK revolution (Frank, 2003).

Kim uses the National Defence Commission to implement this policy. I noted earlier that all North Koreans are in the military, one way or another. In addition to the KPA, the paramilitary and reserve forces are the primary entities by which another seven million adults in the DPRK are available for military purposes. Youth and children are also mobilized by the Red Youth Guard.

All these entities are controlled by Kim Jong Il. As a result, most key decisions are never made. Those that are made reflect the informational organizational problems of formulation and implementation associated with centralized rule, and the idiosyncratic characteristics arising from personalized rule. In many respects, Kim runs the DPRK as an absolute king similar to orthodox pre-modern Korean government, overlaid by the modern means of administrative and political control of every aspect of individual life, to an extent that is unique to the DPRK, exceeds the control achieved anywhere else in the world today, and probably is the tightest control over individual life of any political system in human history. Thus, the “Supreme People’s Assembly” of “elected” officials is a purely rubber stamp entity that meets rarely, and then only to ink major policy pronouncements by Kim Jong Il.

One consequence of such a system, apart from its obvious opacity to outsiders, is that it is unpredictable. Perched at the top and surrounded by competing cliques, Kim controls competition for access and influence by internal security agencies that conduct intimate surveillance, and a system of systematic purges combined with continuous rotation of officials across organizations, into provincial or external postings, prison camp, and in important cases, execution.

A particularly important dimension of social control are the legal practice of multi-generational punishment in the DPRK; and the use of prison camps, especially those used to control low-status and actual or potentially alienated individuals. The Prison’s Camps Bureau maintains about twelve gulags in mountainous areas that contain about 200,000 people. Human rights investigators have used open source remote sensing imagery cross-referenced with refugee and defector reports to document these sites in great detail (Hawk, 2003).

Kim’s control apparatus rests on three primary internal security organizations which have overlapping and competing responsibilities—a characteristic that is likely not an oversight but by design. These are the State Security Department, the Ministry of People’s Security (formerly the Ministry of Public Security) and the Security Command (Janes, November 16, 2009). Each of these agencies is also required to be self-funding and operate networks of factories, trading companies, and smuggling operations that often lead to international arrests, sanctions, and deportations outside the DPRK. The novelist “James Church” (the nom de plume of a former US intelligence officer) has written three revealing novels about how a North Korean detective, Inspector O, survives in such a system.

Finally, although it has endured for decades, this system could unravel quickly should Kim appear to lose grip, die, or attempt to transfer power by succession to another member of the Kim clique. However, there are no signs of collapse and the means of control are so tight that risk analysts judge the DPRK’s military and security stability to be higher than that of China (see Janes graphic below), the likely result of central instability would be that another Kim would take over, backed by the military; or a military modernizing regime would be installed.

5. SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

A. ROK Social Development

The ROK has achieved OECD standards of social development. The UNDP Human Development Index (a composite of indices for life expectancy, education, and living standard) for the ROK in 2007 was 0.937, or 26th out of 182 countries included in the UNDP HDI (UNDP, 2009).

With regard to other aspects of human development not captured by the HDI, the ROK scores less well in comparative terms:

Gender: The ROK ranks 61st out of 109 countries in the composite empowerment measure GEM, with a value of 0.554. (UNDP, 2009)

Migration: The ROK has a low rate of emigration (3 percent per year of which 50 percent go to North America); it also has a very low rate of immigration, with about ½ million migrants representing only 1.2 percent of the population. (UNDP, 2009)

Telecommunications: The ROK has a high density of telephony ((21.3 million land lines, 46 million cell phones in 2008). It has 38 million internet users.

Source: Jane’s Country Stability Ratings, 2010

Country Stability Ratings provide a quantitative assessment of the stability environment of a country or autonomous territory. All sovereign countries, non-contiguous autonomous territories and de facto independent entities are included in the assessments.

To gauge stability, 24 factors (that rely on various objective sub-factors) are rated. The 24 factors are classified within five distinct groupings, namely political, social, economic, external and military and security. The stability of each factor is assessed by the Country Stability team as between 0 and 9. The various factors are then weighted according to the importance to the particular country’s stability. Stability in each of these groupings is provided, with 0 being entirely unstable and 100 stable.

The weighted factors are also used to produce an overall territory stability rating, from 0 (unstable) to 100 (stable).