North Korea: Migration Patterns and Prospects

Special Report, November 4, 2010

Courtland Robinson

This paper originally presented at the conference “The Korea Project: Planning for the Long Term,” sponsored by the Korean Studies Institute, USC, and Korea Chair, CSIS. Held at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, August 20-21, 2010.

——————–

CONTENTS

II. Article by Courtland Robinson

V. Nautilus invites your responses

I. Introduction

Courtland Robinson, Assistant Professor at the Center for Refugee and Disaster Response at the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, writes “It is my view that migration, in and of itself, is not likely to bring about regime collapse or change, but it can serve either as a catalyst to unification or as a hindrance, depending on how it is “managed.” I put that word in quotes because much that passes for migration management is more a matter of mismanagement, further reinforcing the view that migration will seek its own terms despite (and often in reaction to) the policies and programs that seek to regulate it.”

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on contentious topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Article by Courtland Robinson

-“North Korea: Migration Patterns and Prospects”

By Courtland Robinson, PhD

Introduction

The invitation to prepare a paper for The Korea Project: Planning for the Future asked me to consider migration as a functional sector in the context of Korean unification. I was specifically asked to consider “famine and distress migration” with a view to answering several questions: “What lessons can be learned that may be applicable to Korea? What are the attributes of distress migration and the necessary requirements to prevent such migration?” In doing so, I was asked to draw on “other empirical cases and theories” and not necessarily with “specific knowledge of North Korea.”

This paper present some of the theoretical literature and case studies on famine and distress migration while also describing some of what I have learned about North Korean migration, based on my own research and my review of materials published in the last two decades. My work began with a study of famine migration (as well as mortality and fertility) during the period 1995-1998, but has since focused on the evolving patterns of migration from North Korea, including cross-border movements into China (refugees, asylum-seekers and other vulnerable populations including trafficked women, and children born to North Korean women in China) as well as regional migration within Asia, and resettlement in third countries (particularly South Korea but also the United States and other countries).

It is my view that migration, in and of itself, is not likely to bring about regime collapse or change, but it can serve either as a catalyst to unification or as a hindrance, depending on how it is “managed.” I put that word in quotes because much that passes for migration management is more a matter of mismanagement, further reinforcing the view that migration will seek its own terms despite (and often in reaction to) the policies and programs that seek to regulate it. That said, I would suggest the most productive approach to migration from North Korea would be:

1. To acknowledge that distress migration will occur at some level given the hardships of life in North Korea. Some scenarios—including complications in the succession of leadership, rising food insecurity and possible famine conditions, deteriorating population health and possible epidemics, even conflict between North and South Korea—must be modeled with contingency plans for rapid, large-scale internal and international migration.

2. To build on the current evolving patterns of migration out of North Korea while reinforcing opportunities for (and rights-based approaches to) migration for labor, marriage and family reunification.

3. To enlist the services of key governmental , international, non-governmental organizations, and research institutions, with access to information on North and South Korea, to make estimates of the demographic , social and health characteristics of North Koreans likely to seek to migrate to South Korea (and possible alternative flows) in the context of different unification scenarios.

The paper will focus first on a review of famine concepts and definitions, including migration as one characteristic of the famine “syndrome.” I will then review some of the data on migration from North Korea in the past 15 years, and conclude with a discussion of several migration scenarios in the context of reunification.

Famine and Distress Migration: A Conceptual Framework

Famine is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “extreme and general scarcity of food, in a town, country, etc.; an instance of this, a period of extreme and general dearth.” The first OED citation comes from Piers Plowman (1362): “Famyn schal a-Ryse, fruites shall fayle thorw Flodes and foul weder,” setting the problem clearly in the context of natural disaster. Throughout the centuries, famines have been attributed most commonly to natural causes like floods and droughts, which destroy crops thus leading to food shortage and starvation. After climate, another common explanation for famine has been population or, more precisely, over-population. In 1981, Robson recapitulated the Malthusian argument that “Increases in famine are now being predicted because of recognition that there is a finite limit to food production potential in the world and that man appears to be unable to control population growth at a rate that can be supported by the available food resources.”[1]

More recent analysis has tended to see the phenomenon of famine not as a force of nature but as a human-made disaster, “a product of economic marginalization, population pressures on land, environmental stress and political struggle.”[2] In this construct, famine no longer is a natural, inevitable phenomenon but an unnatural and preventable one. Corollary to this runs the argument that the problem is not one of food availability but of access to, and command over, food. As economist Amartya Sen put it: “Starvation is a matter of some people not having enough food to eat, and not a matter of there being not enough food to eat.”[3]

Sen has argued that the traditional approach of attributing famine to “food availability decline (FAD approach for short)” is, ultimately, “clueless” in understanding the dynamics of famine even though it has “some superficial plausibility…it seems natural to sense a shortage of food when people die as a result of not having enough food. The FAD approach also fits in well with the Malthusian long-run analysis of increased mortality as food supply falls relative to the size of the population.”[4] Sen instead proposed what he termed the “entitlement approach” to starvation and famines:

The entitlement approach to starvation and famines concentrates on the ability of people to command food through the legal means available in the society, including the use of production possibilities, trade opportunities, entitlements vis-à-vis the state, and other methods of acquiring food…Ownership of food is one of the most primitive property rights, and in each society there are rules governing this right. The entitlement approach concentrates on each person’s entitlements to commodity bundles including food, and views starvation as resulting from a failure to be entitled to any bundle with enough food.[5]In a “fully directed economy,” Sen wrote, each person “may simply get a particular commodity bundle which is assigned to him.” He gave the example of residents of nursing homes or mental hospitals. (By Sen’s definition, North Korea, at least until the late1990s, could be described as a “fully directed economy.”) More typically, there is a menu of choices available, even to people of limited means:For example, a peasant has his land, labour power, and a few other resources, which together make up his endowment. Starting from that endowment he can produce a bundle of food that will be his. Or, by selling his labour power, he can get a wage and with that buy commodities, including food. Or he can grow some cash crops and sell them to buy food and other commodities. There are many other possibilities. The set of all such commodity bundles in a given economic situation is the exchange entitlement of the endowment… The ‘starvation set’ of endowments consists of those endowment bundles such that the exchange entitlement sets corresponding to them contains no bundles satisfying his minimum food requirements.[6]Sen points out that the term “entitlement” has a descriptive rather than normative use, referring to legal rather than moral rights. In Arnold’s description, “the term ‘entitlement’ is used to signify legally sanctioned and economically operative rights of access to resources that give control over food or can be exchanged for it.”[7] This access could be obtained through production, trade, labor, property rights and inheritance, or a state’s welfare provisions. “Entitlement”, in this usage, does not encompass looting or other non-legal means of obtaining food. A hungry crowd outside a well-stocked and well-locked warehouse lacks a legal entitlement to break in and eat, even though they may have a moral right to do so.Sen’s 1981 work, Poverty and Famine, employs a case study approach to the analysis of several 20th century famines, including the Great Bengal Famine of 1943-44, the Ethiopian famine in 1973-74, the Bangladesh famine in 1974, and famines in Africa’s Sahel region in the 1970s. He demonstrated that during the Bengal famine of 1943, in which as many as 3 million people died in excess of normal mortality, the rice supply had been “exceptionally high.” The availability of food grains was at least 11 percent higher in 1943 than it was in 1941, when there had been no famine. [8] The exchange entitlement of low-wage laborers, however, shifted dramatically in 1943 in the face of steep price increases. The most seriously affected were fishermen, transporters and agricultural laborers, whose wages did not keep pace with rising rice prices. Residents of Calcutta, however, were largely spared the price effects due to the availability of government-subsidized rice through a rationing system. Bengal was an example of a “boom famine related to powerful inflationary pressures initiated by public expenditure expansion” in a war economy. [9]The contributions of Sen’s “entitlement approach” are, first of all, that it analyzes famines as “economic disasters not as just food crises.”[10] In so doing, it encouraged a closer examination of the nature, causes and consequences of famine. By mapping the patterns of entitlement failure and resilience, Sen concluded that “in the terrible history of famines in the world, it is hard to find a case in which a famine has occurred in a country with a free press and an active opposition within a democratic system:”The diverse political freedoms that are available in a democratic state, including regular elections, free newspapers and freedom of speech, must be seen as the real force behind the elimination of famines. Here again, it appears that one set of freedoms—to criticize, publish and vote—are usually linked with other types of freedoms, such as the freedom to escape starvation and famine mortality.[11]Sen contrasted the case in India, where “there has been no famine since independence, despite momentous droughts, floods, and other catastrophes” with that of the Great Leap Famine in China, 1958-61, which caused as many as 30 million premature deaths and “was partly caused by the continuation of disastrous government policies, and that in turn was possible because of the non-democratic nature of the Chinese polity.” Elaborating these remarks in his 1999 book, Development as Freedom, Sen wrote:The so-called Great Leap Forward initiated in the late 1950s had been a massive failure, but the Chinese government refused to admit that and continued to pursue dogmatically much the same disastrous policies for three more years. It is hard to imagine that anything like this could have happened in a country that goes to the polls regularly and that has an independent press. During that terrible calamity the government faced no pressure from newspapers, which were controlled, and none from opposition parties, which were absent. The lack of a free system of news distribution also misled the government itself, fed by its own propaganda and by rosy reports of local party officials competing for credit in Beijing.[12]While Sen’s “entitlement approach” has been widely cited and widely respected (earning him the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1998) it has not gone unchallenged. Arnold credits Sen’s hypothesis with doing “much to revitalize and reorient the discussion of famine. In particular, it has drawn attention to famine’s uneven and discriminatory impact.” He doubts, however, “whether Sen has really provided a theory of famine causation…so much as given an explanation of how famines develop once they have (for whatever reason) been set in motion.” [13]Arnold offers the examples of the Orissa famine of 1866 and the China famine of 1876-79 as instances of famines where there is “clear evidence of a serious shortfall in food availability—whether due to adverse climate, insect pests and other causes, and where, because of transport difficulties or economic and political factors, there was little possibility of importing sufficient food to compensate for local losses.” (Though the point is well taken, it is telling that Arnold’s examples come from the 19th and not the 20th century. Climate remains a force unto itself, but pests are a more containable threat, transport is not nearly so difficult and, if sufficient food is not available to compensate for local losses, national or international political factors are the most likely culprit.)Despite some critiques of Sen’s entitlement approach, it provides a framework within which to view 20th (and 21st) century famines as largely human-made and preventable, and that failures of political accountability are principally to blame for their perpetuation in modern times.Taking the view that famine is not a discrete event but a lengthy and multi-faceted social process, a “community syndrome,” or a “complex socio-economic phenomenon,” it is possible to list various “symptoms” or “crisis adjustments” that famine engenders in a population. These include:• Intensification of ritual• Eating of “alternative” foods• Selling of assets• Social breakdown• Migration• Malnutrition and morbidity• Lowered fertility• Increased mortalitySome of these symptoms may be seen as strategic adjustments, either preemptive or reactive, to cope with an evolving crisis while other symptoms—particularly morbidity and mortality—represent a failure of such strategies to protect life and health. As the situation grows more desperate, coping strategies become less “reversible”, more risky and, ultimately may threaten not just livelihood but life itself. For purposes of space, this paper will focus on only two famine symptoms or adjustments, which in the context of North Korea in particular, are highly correlated: societal breakdown and migration.Social breakdown Field argued that no definition of famine would be complete if it “fails to capture the extent of social disintegration that usually accompanies the downward slide into famine conditions:” indeed, he insisted that “societal breakdown” is the “essence” of famine. He cited the crumbling of “social reciprocities” and the increase of “hoarding and related pathologies (smuggling, black market profiteering, crime).”[14] As Scrimshaw elaborates,Initially, there is likely to be mutual help among kinship groups or friends and attempts at preferential concern for the vulnerable, especially children and the elderly. However, as famine progresses in severity and duration, normal social behavior gradually disappears, including personal pride and sense of family ties, leaving only a struggle for personal survival. In society as a whole, the pattern of family breakdown is seen in magnified form, with increasing disintegration of social structure, lawlessness, and abandonment of cooperative efforts as famine reaches its later stages. [15]According to Jelliffe and Jelliffe, “Any activity which can obtain food may be employed ultimately, including theft, riots, prostitution, and the selling of children.” [16] As both Field and Alamgir note, the breakdown of social bonds leads to family disintegration—“families divide in search of work or succor; wives may even be cast adrift and children sold”[17] —or families, in whole or in part, may be uprooted from their home and lands through the distress sale of assets.[18] Under such conditions, “it may be said that famine breeds famine, since organized activities of society may become disrupted to the point that purposeful action to improve conditions becomes impossible.” [19] Unchecked, the slide into social breakdown can lead to demonstrations, riots, anarchy and revolt.Migration Yip asserts that “Population migration, a sign widely regarded as an intermediate warning sign of famine, is actually a late sign of famine. Careful review of the process of famine development indicates that by the time people have left their communities to seek food, there is already extensive suffering.” In the very next sentence, however, Yip reveals a particular bias about the concept of migration: “Any congregation [italics added] of displaced populations almost assures high morbidity and mortality related to infectious diseases and reduced host resistance.” [20] Mass movements of people such that they end up congregated in camps and settlements may indeed happen in the latter stages of famine, but there are many earlier migratory responses to famine.In a 1992 publication, Yip’s colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control (which labeled “population movement” as a “leading indicator” and “population migration” as an “intermediate indicator” of famine) offered a somewhat more nuanced interpretation of migration in response to famine: “Populations experiencing famine may or may not displace themselves in order to improve food availability. Initially, male family members may migrate to cities or neighboring countries to seek employment. During a full-scale famine, whole families and villages may flee to other regions or countries in a desperate search for food. [21]Young and Jaspars suggest that “If food security conditions do not improve and famine progresses, people are forced to use coping strategies that become increasingly threatening to the survival of their livelihoods. Productive assets are sold off, until eventually people have no other choice but to starve or migrate in search of relief or other means of support.” [22] Corbett also refers to the “mass migration to relief camps or roadsides” during famine as “distress migration” and suggests that it “may only be the last in a sequence of household responses to famine conditions and a clear indication that many other responses have failed.” [23]In examining famine-related migration, then, it is important to distinguish not only who in the household is migrating but where, for what purpose, and for how long. Movements by individual members of the household to nearby locations for purposes of employment may be early indicators or symptoms of famine. As the crisis persists or intensifies, migration may encompass whole families or entire communities who are faced with a choice to “starve or migrate.”Patterns of North Korean Migration: 1995-2010Though there are a great many unknowns about migration within and outside of North Korea in the last 15 years or so, some patterns can be identified and estimates made, focusing on three types of migration: internal, migration to China, and international resettlement (particularly in South Korea).Internal Migration The two most recent censuses in the DPRK, conducted in 1993 and in 2008, record no data on international migration (one official analysis of the 1993 census noted that “migrant numbers going out and coming into our country were neglected”[24]) and data on internal migration were limited to urbanization rates in 1993. [25] The 2008 census still contained no international migration data but internal migration coverage was expanded to include provincial migration within the last five years. [26] The data suggested that 234,817 (out of a population of 23,349,859) had moved from one province to another in the last five years, or scarcely 1 percent. The unofficial picture is one of a great deal more mobility, much of it “irregular.” A study I conducted in China in 1998 of nearly 3,000 North Korean refugees and migrants asked about movements into and out of the household of more than one month suggested a net migration rate of 18.7%, with much of the internal movement “distress migration.” [27] More than 30% said their main reason for moving was to “search for food;” and more than one-fifth of the out-migrants were children under 15.With continued economic hardship and chronic food insecurity, at least in some parts of country, coupled with periodic natural disasters, it seems quite likely that internal migration continues at levels well above what official rates suggest. It also seems reasonable to conclude that much of this movement can be characterized as “distress migration” and “irregular” meaning that it takes place without official sanction.Migration to China Migration of Koreans into Northeast China dates back to at least the 1880s when poor farmers crossed the border to escape economic hardship (Liang & Dohm, 2006). [28] Migration accelerated with the Japanese occupation of Korean in 1910 but declined when the Communists came to power in China in 1949 and Korea became a divided country. The recent surge in cross-border movement of North Koreans into China likely began in the mid-1990s but probably did not peak until 1998 or 1999, several years after the peak of the famine in North Korea in 1996-1997. For the last twelve years, North Koreans have been crossing the northern border into China, seeking to escape food shortages, economic hardship, and state repression in their own country. Most of these North Koreans have left their own country and entered the neighboring People’s Republic of China (PRC) without travel authorization or documentation. Given their undocumented status and the repressive nature of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), these North Koreans have been labeled refugees and asylum seekers by those who seek to protect them. [29] Conversely, they are called illegal migrants by both the Chinese and the North Korean governments. Estimation of their numbers and migration trends over time has proved logistically difficult and politically sensitive and the only point on which their defenders and detractors seem to be able to agree is that North Koreans in China are difficult to count. As noted by a 2007 report from the Congressional Research Service (2007):There is little reliable information on the size and composition of the North Korean population located in China. Estimates range from as low as 10,000 (the official Chinese estimate) to 300,000 or more. Press reports commonly cite a figure of 100,000 to 300,000. In 2006, the State Department estimated the numbers to be between 30,000 and 50,000, down from the 75,000 to 125,000 range it projected in 2000. UNHCR also uses the 2006 range (30,000 to 50,000) as a working figure. UNHCR has not been given access to conduct a systematic survey. Estimating the numbers is made more difficult because most North Koreans are in hiding, some move back and forth across the border—either voluntarily to bring food and/or hard currency from China or North Korea—or because they are forcibly repatriated…Clearly, the refugees’ need to avoid detection, coupled with a lack of access by international organizations, make it difficult to assess the full scope of the refugee problem.In late 2009, my colleagues and I conducted an estimation of the population of North Korean refugees and migrants in three provinces in Northeast China: Heilongjiang, Jilin (not including Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture) and Liaoning. The primary objective of this research was to estimate the total population of North Korean refugees and irregular migrants in selected areas in Northeastern China, including the estimated number of children in these provinces who were born to North Korean women in China. The secondary objective was to identify key characteristics of children born to North Korean women in China, including household composition, migration patterns, and current living conditions. Population-focused interviews with 324 respondents in 108 randomly selected sites in three provinces gave evidence of the following trends:• North Korean Population Decline in China. Comparing the NK population estimates from 1998 to 2009, it is clear there has been a dramatic decline in the North Korean population in Northeast China, from around 33,700 North Korean refugees and migrants in 1998 to perhaps 5,700 in 2009 (see tables at end of paper). Factoring in Yanbian estimates, total numbers of North Koreans in China have declined from around 75,000 in 1998 to around 10,000 in 2009. When North Koreans first began crossing into China in significant numbers in 1998, it was in the wake of a severe famine and only four years after the death of Kim Il Sung. In the face of sustained food shortages, elevated mortality, and deep uncertainty about the future, even flight into a foreign country offered better prospects than staying home. More than a decade later, hardships continue for the North Korean people in the face of continued food shortages, a moribund economy, periodic natural disasters, and a government unwilling to make the reforms necessary to improve the health, welfare, and human rights of the general population. Reasons for the declining population include tighter border security, increased migration to South Korea and other countries, and lower expectations of what is available in China.• Increase in Proportion of North Korean Women. The proportion of the North Korean refugee and migrant population in Northeast China who are female rose from 50% in 1998, to 54% in 2002, then to more than 77% in 2009. This tracks very closely with the 2007 Yanbian study data, which showed that the proportion of North Korean females was around 60% in 1998, growing slightly 2002 to about 65% in 2002 and then to 72% in 2007. In Heilongjiang, the proportion of North Korean women was only around 41% in 1998, when male migration for work in the timber industry and seasonal agriculture tended to predominate. By 2002, the proportion female was around 50% in Heilongjiang and by 2009 rose to around 80%.• Increase in China-born Children. The Northeast China study suggests that, outside of Yanbian, the number of children born to North Korean women in China rose from around 4,000 in 1998, to 6,200 in 2002, then to 6,900 in 2009. In Yanbian, the number might have declined from around 4,000 in 1998, to perhaps 2,700 in 2002, and then risen to around 3,500 in 2009. Assuming the data are basically correct, this suggests that more China-born children in Yanbian either followed their mothers into migration to other countries or, given the proximity to North Korea, may have repatriated (or been deported) with their mothers. In the Northeastern provinces outside of Yanbian, the China-born children more frequently have tended to stay behind, or been left behind, even as their mothers and other North Koreans moved away. We estimate a mid-range population of 10,500 China-born children in 2009, with a low-range of around 5,200 and a high-range estimate of 15,200. Basically, there are slightly more children born to North Korean women in China than there are total North Korean-born populations.Though China is signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, it does not recognize North Korean claims to asylum as valid. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has declared all North Koreans in China to be “persons of concern;” as such, in the context of “Convention Plus,” they would all be encompassed within the Framework for Durable Solutions for Refugees and Persons of Concern. Durable solutions, in this sense, primarily refer to voluntary repatriation, local integration, and resettlement, but also development assistance pending a durable solution. [30]International Resettlement. Because the main route out of North Korea is through China, and because China does not recognize North Korean claims to asylum or refugee status and, indeed, maintains a general policy that undocumented North Koreans in China are subject to detention and deportation, any recourse that North Korean refugees and asylum seekers have to international resettlement depends on either their ability to find safe haven in a foreign embassy in China or on their ability to find their way through China to seek resettlement from the relative safety of a neighboring country like Mongolia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam or Russia.Since 1994, more than 20,000 North Koreans have found permanent settlement in other countries. A recent GAO report estimated that, as of March 2010, a total of 1211 North Koreans had filed asylum applications in England, Germany and Canada, of whom 617 had been granted asylum. [31] As of the same date, the United States had opened 238 North Korean refugee applications and admitted 94 into the country. The great majority of North Koreans who settle permanently outside their country (discounting those who have managed to remain in China for multiple years) move to South Korea, where they are received not as refugees but as citizens.Article 3 of the South Korean Constitution states that “The territory of the Republic of Korea shall consist of the Korean Peninsula and its adjacent islands.” The 1997 Act on the Protection and Settlement Support of Residents Escaping from North Korea, Article 1 stated as its purpose to promote “protection and support necessary to help North Korean escapees from the area north of the Military Demarcation Line (hereinafter referred to as ‘North Korea’) and desiring protection from the Republic of Korea, as swiftly as possible in order to adapt and stabilize, all spheres of their lives, including political, economic, social and cultural.” When a North Korean “escapee” who does not fall under exclusion clauses for protection, enters South Korea, the processes of acquisition of nationality and personal identification registry are completed during his/her stay at Hanawon Center, a government-funded facility for social integration of North Koreans into South Korea. [32]Though the Ministry of Unification appears reluctant to give out more than rudimentary statistics on the so-called talpukja (“those who have fled the north”) or saetomin (‘new settlers”) population, it is clear that the migration has accelerated (with over 2,500 new arrivals per year since 2007) and that the proportion of women has increased to comprise more than 77 percent of the new arrival caseload in the past several years and more than two-thirds of the 17,984 North Koreans settled in South Korea since 1949 (see Figure 1 on page 16). Resettlement assistance is relatively generous but integration has been difficult and the North Korean settlers are viewed with distinctly mixed feelings by their southern hosts.Future ProspectsWhether or not it is reasonable to imagine a plausible reunification scenario within the near term (say, 3-5 years), it is certainly reasonable to assume that things could get worse before they get any better. As such, I would say that the best way to prepare for reunification, in terms of migration, would be to enhance capacity to manage multiple streams of migration, including distress, family reunification, and labor. Within the context of distress migration, there are likely to be multiple categories of displacement that have distinct though overlapping profiles of vulnerability. These include refugees and asylum seekers (who leave based on a well-founded fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a social group, or political opinion), women whose coping strategy in leaving North Korea to marry a Chinese man (and are at risk of trafficking and other forms of exploitation), and children born in China to these women.Scenarios and contingency plans for large-scale internal and international migration. Most scenarios about North Korea that include any discussion of migration focus mainly or exclusively on refugee outflows. Thompson and Freeman, in examining possible Chinese planning for, and response to, large-scale outflows from North Korea, considered three scenarios: (1) a steadily increasing flow (“a trickle to a flood”), (2) a sanctioned outpouring (“Mariel outpouring”) and (3) a mass exodus caused by regime collapse or similar breakdown (“catastrophic collapse”). [33]In the first of Thompson and Freeman’s scenarios, “the current pressure for North Koreans to flee to China for food, income or sanctuary increases dramatically due to deteriorating conditions within the country, such as famine or natural disaster.” It is possible that a dramatic deterioration in food security or a calamitous disaster would lead to sharp increases in cross-border movements but, in fact, movements into China have declined dramatically in the last six years, not due to improvements in material conditions in North Korea but to enhanced border security and, one might say, a growing awareness on the part of North Koreans of what movement into China does, and more particularly, does not offer. Large-scale movements have been predicted by a number of non-governmental organizations in recent years but have not come to pass. It may be that some of the cross-border movement has been replaced by greater dynamism in internal migration and displacement but this has not been documented.The “Mariel scenario,”—named after the mass expulsion/exodus to the United States of more than 125,000 Cubans between April and October 198, including large numbers released by the Castro regime from prisons and mental institutions—would involve an intentional policy of the North Korean government to expel, or encourage departure of, “’unproductive’ members of society, including the elderly and disabled. They might also expel mental patients, prisoners, violent criminals and marginal workers from labor camps, foisting ‘problem citizens’ on China.” [34] To some extent, this already has occurred, with North Korea permitting significant movements into China in 1998, likely as a safety valve to alleviate some of the problems of population hunger and hardship. Evidence from my research also supports the view that a disproportionate number of the early cross-border refugees and migrants were members of the “hostile” classes.“Catastrophic collapse,” the third scenario, could lead to the largest numbers of refugees fleeing. A 2007 study by the Bank of Korea estimated that as many as 3 million North Koreans would be likely to flee, with most heading to South Korea but many crossing into China.[35] It is possible that China would not permit such numbers to cross the border at all, choosing instead to insist that any aid be provided to relief camps set up on the North Korean side. There may be some form of international assistance but China is not likely to offer the kind of aid it once provided to Vietnamese refugees in the 1980s, and indeed has surely learned from the experience of other Asian neighbors who offered temporary asylum to Vietnamese and other Indochinese refugees only to find themselves hosting a large-scale international relief effort and long-term refugee populations.Thompson and Freeman are surely correct in stating that, in the end, “in all scenarios, Chinese concerns remain the same: primarily ensuring law and order, social stability and continued economic growth. Chinese responses to the crisis will invariably seek to achieve those goals and how it manages refugees should be interpreted in that light. It is unlikely that ideological or altruistic motives will shape policy or actions on the part of Chinese officials in this case.” Given that virtually all migration from North Korea in the last 10-15 years, indeed in the post-war history of the DPRK, has either transited or ended in China, its role is critical in shaping a paradigm shift from migration as both cause and effect of political antagonism to a possible focus of international dialogue and cooperation.Enhancing saf(er) migration. The brief I was given for this paper was to identify the “attributes of distress migration and the necessary requirements to prevent such migration” in the context of a build-up (or breakdown?) to reunification. Given that “distress migration” is characterized by some element of compulsion, coercion or lack of choice—whether due to natural or human-made disaster, conflict, widespread human rights abuse, or other hardship that threatens life and livelihood—the only legitimate way to prevent distress migration is to prevent distress in the first place. Failing that, it would be necessary to promote alternatives to the kinds of migration that impose additional burdens of distress upon those who move.The time to begin constructing and enhancing these safe (or safer) alternatives to the current, mainly high-risk modes of migration is not in reaction to the three crisis scenarios outlined above (and their myriad permutations), but proactively, indeed now. A new discussion of North Korean migration must begin by framing an understanding of population mobility within and outside the country as something more than a simple threat to stability or mark of instability. The migration of North Koreans in the last 12-15 years has always encompassed a mix of motives—food, health, shelter, asylum, family formation, family reunification, labor/livelihood, and more. The problem is that the discussion of this migration (and the policy/program options that either are or should be available) has been dominated by a dichotomous question: are they or are they not refugees? The two principal countries who say they are not—North Korea and China—control both sides of the border that virtually all of the migrants must cross. Those who would argue for at least refugee-like protections—the United States and other Western democracies as well as UNHCR and human rights organizations—have no direct access to these migrant populations at their greatest vulnerability in the border regions. There are no quick or easy answers to this dilemma but one approach would be to broaden the framework to encourage all the stakeholder countries to consider a more complex range of migration categories and, in so doing, perhaps to acknowledge that safer migration options may be in their self-interest.It would be in China’s interests to provide naturalization for the more than 10,000 children born to Chinese fathers and North Korean mothers, just as it would help to stabilize rural communities in Northeast China to grant at least temporary protection if not more permanent status to the North Korean mothers and other North Koreans who have been living peacefully in the area. It would also be in China’s interests to protect migrant adults and children from the risk of trafficking and to provide access to basic health care as a public health benefit as well as education for school-age children and other core social services.Similarly, it would be in North Korea’s interests to permit households with motives of family reunification, labor and economic betterment, or simply survival to leave without risk of penalty to themselves or their family members left behind. In this way, North Korea might be encouraged to initiate not a “Mariel scenario” but an informal Orderly Departure Program (ODP), similar to the multilateral program begun in Vietnam in 1979 to permit safe and orderly exodus of populations seeking to leave.For their part, South Korea should continue to resettle North Korean migrants as nationals of one Korea and broaden migration opportunities of Chinese family members of mixed-nationality children. In the context of the Red Cross exchanges of family visits, direct migration of family members from North to South, or South to North, should also be promoted. Finally, the United States in particular but other countries of resettlement should broaden the scope of support for North Korean refugees (both in terms of humanitarian assistance and resettlement) to include acknowledgement of, and support for, other vulnerable populations, including victims of trafficking (including sexual and labor exploitation), stateless children, and other vulnerable migrant populations.Migration forecasting. Finally, we must enlist the services of key governmental , international, non-governmental organizations, and research institutions, with access to information on North and South Korea, to make estimates of the demographic , social and health characteristics of North Koreans likely to seek to migrate to South Korea (and possible alternative flows) in the context of different unification scenarios. During the Korean War, more than one million fled from North to South and several hundred thousand from South to North. [36] While this population itself has aged, and many have died, their family members form a core “interest group” to re-open migration channels. Data from North Korea is sparse, and data on the migrant/refugee population might present a somewhat skewed demographic for deriving broader conclusions about broader migration flows but it is a place to start. There is a need to enhance our picture of the migration from North Korea, beginning with the war and coming up to the present day, encompassing the full range of migration patterns: internal mobility, the evolving migration into and within China, regional migration dynamics, and the settlement and integration of North Koreans in South Korea. Enhancing bilateral and multilateral dialogue on these issues, as well supporting the full engagement of civil society, may be a confidence-building measure in itself and promote the idea that migration need not be an issue that divides countries but one that may, quite literally, bring them together.III. Tables and Graphs

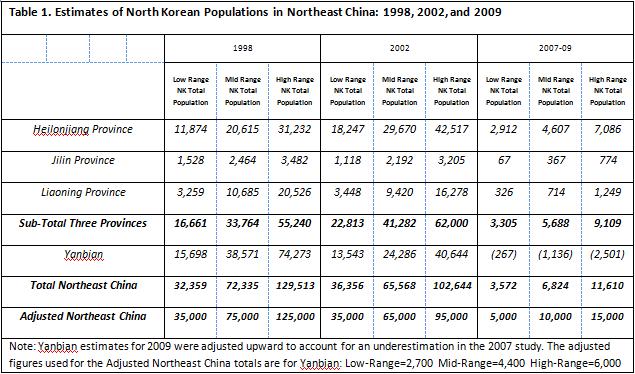

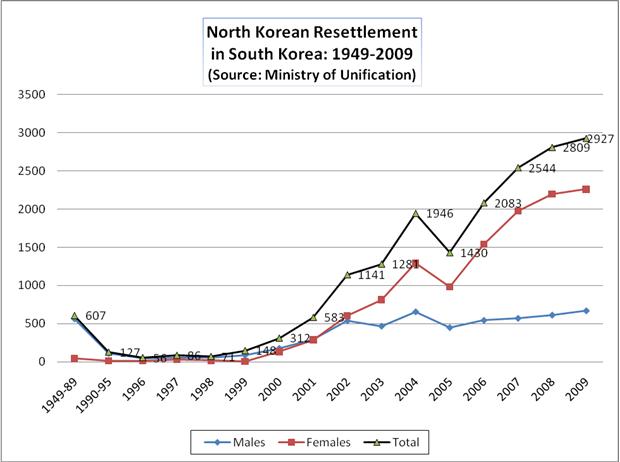

Figure 1. North Korean Resettlement in South Korea: 1949-2009

Global Problem Solving Book: "Complexity, Security, and Civil Society in East Asia: Foreign Policies and the Korean Peninsula." Download it free!

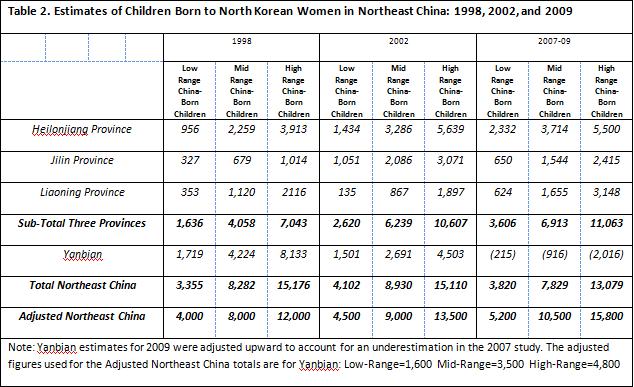

One thought on “North Korea: Migration Patterns and Prospects”