by Peter Hayes and Roger Cavazos

I. Introduction

Peter Hayes and Roger Cavazos analyze information flows to and from China and analyze social media use (especially the use of micro-blogging or “weibos”) and find that those flows allowed a much broader dialogue and even some inclusionary processes regarding national security issues in China. There are also anecdotal, yet illustrative examples of the extent to which these developments likely affected Chinese policy-making. We also argue that China’s government recognizes there is an opportunity to interact with China’s huge “netizen” communities at a speed and volume that exceeds the government’s current capabilities. The dialectical response has been a clamp on information flows until policy and technology are in balance. The new inclusionary processes also allow for a type of participatory government. We also infer that just as information flows inside China are changing, Chinese social media actors will also interact with external security players—states, corporations, and transnational civil society—in new ways that will change the nature of geopolitics in the region. Managing these changes will require new forms of civic diplomacy and a greater emphasis on conducting discussions with China in Chinese language.

Peter Hayes is Executive Director of the Nautilus Institute and a Professor of International Relations at RMIT University. Roger Cavazos is a Nautilus Institute Associate and retired US military officer with assignments in the intelligence and policy communities.

Many of the findings from this paper were presented at a conference titled “Sino-U.S. Relations, Transparency and Governance”. The conference was organized by the Institute of Communication and Culture (Peking University); Center of Global Governance (Peking University) and Hong Kong International Strategic Studies Society. Several media organizations from Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao and overseas covered the conference. In particular here are links to coverage in short-form Chinese, 罗杰-卡瓦佐斯:中国参与式政治正在崛起 and long-form Chinese 羅傑•卡瓦佐斯:中國參與式政治正在崛起. For more information such as the briefing that was presented, please contact Nautilus.

The authors thank Adam Segal for his comments and insights on China’s Internet.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Special Report by PETER HAYES and Roger Cavazos

Internet Events, Social Media and National Security in China

Most US national security engagement with Chinese counterparts is conducted at the level of Beijing-based elites, who formulate and implement China’s national security and foreign policies. This contact is often undertaken during face-to-face visits at conferences or round-tables (sometimes on extended fellowships and study tours) and results in the formation of US-China transnational networks of “senior influentials” who participate in official track 1.0, semi-official track 1.5, or non-official/non-state track 2.0 meetings and dialogues. This process has its virtual analog with private and public information services. Many of these services are produced in the United States, written in English (but increasingly also in Chinese) and aim to service the information needs of Chinese counterparts and, to a lesser extent, eliciting and airing their views.

Although this conventional communication process has been effective to a point in aligning perceptions and creating common understandings between outsiders and Chinese counterparts on critical security issues, its effectiveness in achieving genuine, in-depth communication is questionable at best. In fact, it may now be disconnected from a critical and massive shift in information flows within China itself. The way in which Chinese national security elites communicate with each other, the velocity of information flows and the explosion of non-elite Chinese voices mark an abrupt system-level change in the information milieu in which Chinese national security and foreign policy decisions are made. This transformative shift also enables external actors to communicate not only with official security circles, but also with influential Chinese civil society voices who inform, reflect, monitor and evaluate policy decisions. On matters related to nuclear security and non-state actors who originate and operate in civil society, such engagement is critical; possibly more so than direct engagement of central officials which represents a change to the dialectic of closed, elite decision-making and open, popular discussion.

In the following section we explain why it is critical to respond to this development rather than propose to do more of the same conventional communication with security elites in China. China’s recent measures such as criminalizing social media voices who were judged to be circulating too many views or spreading rumors too often may be viewed as a dialectic response to the speedy rise of the virtual citizen or “netizens” voice designed to induce self-censorship. The operative dialectic here is one of wen (文)and wu (武); where wen are the rewards to create an ordered, civil society and wu are coercive or compellent measures to prevent misconduct.

However, we believe that this heavy-handed control approach will fail to suppress the irresistible urge of wired Chinese to express themselves on critical security issues. The sheer volume of new voices portends the rise of a new force at breathtaking speed in the formation of Chinese foreign policy and security deliberations. As such, it also poses a massive challenge to external actors—states, corporations, and civil society organizations—that must respond to China’s policies on geo-strategic issues. Conventional public and complex diplomacy will not suffice to meet this challenge. Rather, civic diplomacy by civil society organizations communicating directly and indirectly with their Chinese counterparts is now an imperative, as is communicating with them in Chinese language.

INFORMATION FLOW IN CHINA: A CHANGING LANDSCAPE

Among China’s security and foreign policy elites, positions on policy may diverge over core domestic issues, such as political reform versus democracy. However, when it comes to shared notions such as China’s rightful place in the world, the nature of external threat, and the appropriate geostrategic response—including nuclear and conventional force structures—these elites tend to converge on the status quo. The policy currents that shaped China’s national security and foreign policy orientations were relatively insulated from direct pressure from most entities within Chinese society. This opacity made it difficult to monitor and interpret leading and lagging indicators of policy change or the limits of policy debate in China on many issues, including national security and foreign policy. External information that flows to and from officials is channeled via bureaucracies and is largely controlled by them. Well-known gatekeepers from more or less government-affiliated organizations, institutes, university departments, and even relatively autonomous “think tanks” meet with and extract various “rents” from external visitors, whether they are foreign entities or individuals coming to China for track 1.0, 1.5, or track 2.0 engagements. The “rent” charged for obtaining access to these the security and foreign policy domains is often kept in cumulative guanxi (关系) “accounts” whereby Chinese officials extend assistance to outsiders and expect reciprocity in the future. This is the basis of the intensely personal, networked and fluid forms of power that have historically been and continue to exist at the core of modern Chinese politics.[1]

Chinese security analysts must tread carefully to ensure that what they present to a foreign audience does not transgress what can be said domestically. Thus there is an expectation for self-censorship or, at the very least, a tacit understanding that one’s views will be edited by domestic publishers in any media. Undoubtedly, the bulk of popular use of the Internet and social media concern relatively a-political and low-level issues that do not bear directly on high politics of national security and foreign policy; external and self-censoring ensure that will remain the case for the foreseeable future. Empirical studies by Yang have documented that producers of Chinese social media focuses on nine distinct themes, viz: popular nationalism, rights defense, corruption and power abuse, environment, cultural contention, muckraking, and online charity.[2]

Although foreign policy and security issues are not in the “top nine” themes of social media, as we show below, these issues are already “hot” in Chinese social media. Despite frequent interaction with foreign interlocutors, most Chinese debate on-line is self-contained in that there are few foreigners engaging directly with these on-line discussions. Nonetheless, many members of both the inner and outer circles of China’s security and foreign policymaking elite are also influential netizens. This group carefully reads materials from civil society organizations outside of China. Thus, it is imperative that these readers have access to external publications to ensure that these influential “national security agents” are well informed.

Consequently, much effort has been invested into mapping the institutional terrain, key personnel and entry points whereby information reaches these Chinese organizations and officials.[3] However, the rise of social media has rendered a communication strategy based on connectivity solely with these elite personnel no longer a sufficient information strategy to engage China on security issues. For a start, many foreign policy and security issues, including nuclear weapons related security issues, arise from within China itself and external players are not well informed on them in the first place. Many of these issues (especially economic, social equity, and ecological issues) have led to massive social responses, and bear directly on domestic agendas that determine the stability of the rule of the Chinese Communist Party and the relative power of the local, provincial, and central governments. In other words, the landscape has an unprecedented degree of fluidity due to new actors or “netizens” on social media

Often, the central or provincial governments attempt to manipulate “netizen” use of virtual media to collectively comment on or criticize official policies and actions. Here, scale of participation has shifted by orders of magnitude, to the point where mere quantitative change on a factorial scale has led to qualitative change in the outcome. There are a few thousands of officials who make China’s security and military policy, and with whom one might purport to relate via face-face visits, systematic distribution of emails, and promotion of Internet services. But given that on-line social interactions are the result of network operations on a vast scale (permutations of and that China’s virtual producers and consumers of on-line media now number in the hundreds of millions, forecast to be more than a billion by 2015. Conversations and issues appear without warning and almost instantaneously, China’s mass communication is unprecedented in human history and easily the largest public sphere, by far.

SOCIAL MEDIA IN CHINA

Here, we need first to note the extraordinary speed and breadth of individual connectivity to the Chinese Internet. At the end of 2012, China had about 560 million Internet users.[4] Overall, in 2012, about 156 million users were rural; and about 408 million were urban. In 2011-2012, rural users grew at about 13 percent per year; and urban users at about 5 percent per year.[5]

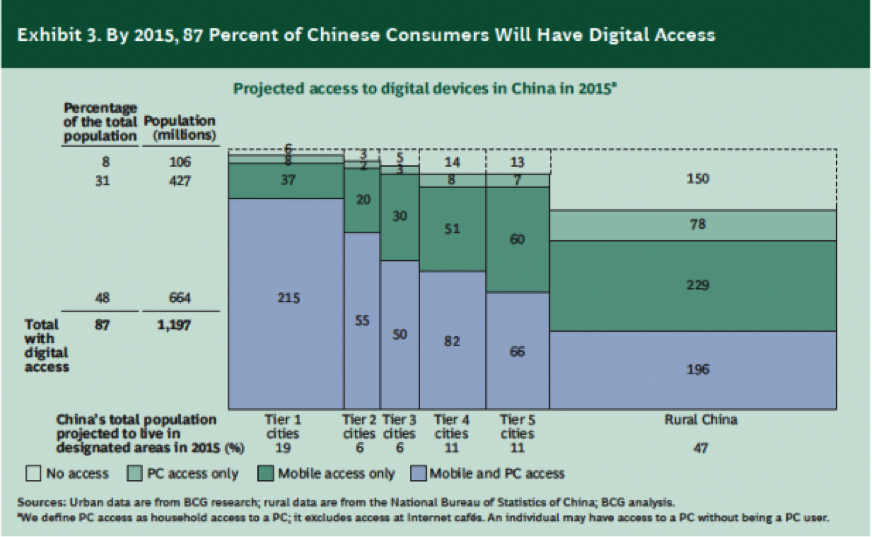

The Chinese government is investing heavily in Broadband China aiming to deliver 20 Mbps bandwidth to urban households, and 4 Mbps in rural households by 2015 according to 12th Five Year Development Plan.[6] Thus, it is reasonable to anticipate continued rapid growth in Internet access and usage in spite of the economic slow-down in China since the global recession in 2008. Some forecasts show total internet connected devices to double to about 1.1 billion by 2015—although many users will have more than 1 type of device (for example, PC and mobile smart or mobile dumb phone) and suggest that the Internet-connected population will rise to 1.2 billion or 87 percent of the national population, by 2015 (see Figure 1). Our own estimate based on 2011-2012 growth rates is that the expansion is more likely to be about 10 percent overall per year, reaching a total Internet connected population of about 700 million or about 53 percent of the national population. In all likelihood, the number will fall somewhere in-between these two estimates, and likely at the lower end of this range. However, it is clear there is no other country with more citizens, in absolute numbers, on the internet.

Figure 1: Forecast Chinese Digital Access to Internet in 2015 (Source: Resonance China at: http://www.resonancechina.com/2010/05/19/china-digital-statistics-2007-2015/)

The biggest expansion will be seen in mobile devices. In 2012 there were about 144 million non-mobile users versus about 422 million mobile Internet users—an increase of 64 million from 2011. The bulk of Internet access was via mobile phones in 2012—around 75 percent. Email, traditional blogs and bulletin boards were in decline in virtual China, and a major shift occurred to use of instant messaging and microblogging on mobile phones—about 202 million of them joining the ranks of microbloggers according to China’s official internet statistics. [7]

Figure 2: Social Media Landscape in China. (Source: Resonance China at: http://www.resonancechina.com/2013/05/06/china-social-media-landscape/resonancechina_china-social-media-landscape/)

WEIBOS (微博)

The use of email, micro-blogs (“weibos” 微博 in Chinese), and other forms of social media over smart phones, tablets, and websites now operates at a velocity and scale in China that is qualitatively and quantitatively new. A micro-blog is a form of electronic media broadcast via the Internet that has typically very small file size content including text, images, or video links, and is mostly created, received, commented on, and forwarded on mobile internet-connected devices such as phones, tablets, etc. Even though microblogs are 140 characters in any language, since each Chinese character can be roughly equivalent to a word, a Chinese Weibo user can post the equivalent of 70 to 140 word since spaces aren’t necessary when using characters. Given the average word length in a Western tweet is about 4 letters, most Western users can only post about 20 words into a microblog such as a Tweet. Many tweets are around 30 characters with another peak at the maximum 140 characters. China’s microblogs therefore, allow for more discussion and more nuance than other languages.

According to China Internet Network Information Center:

Microblog became a mainstream application used by China’s internet users after their development in 2011, and its vast number of users made it a communication center of public opinions. Microblog was reshaping the creation and communication of public opinions. Normal users, opinion leaders and traditional media all turned to microblog to different degrees as a way to obtain news, publish news, express opinions and stir up public opinions, which resulted in high growth rate in number of personal users of microblog in 2012. The change in the behavior of microblog users was more worth noting than the growth in number of users at current stage. The second half of 2012 saw stagnant and even less activity of microblog users on the PC. According to the data of Chinese Internet Data Platform, the number of daily active users of microblog was on a month-on-month decline in the second half of 2012, decreasing from 112 million (peak value) in July to 87 million in December, and the daily visiting time of microblog also dropped from 11.72 million hours (peak value) in July to 7.78 million hours in December. The reasons behind this tendency were as follows: on one hand, microblog lost the sense of freshness to users, which caused the retention to microblog to weaken; on the other hand, part of the microblog users chose to read and post microblog on their mobile phones instead. 202 million microblog users visited microblogs on their mobile phones by the end of 2012, accounting for 65.6% of the microblog users, and the tendency of users to choose mobile internet made microblog one of the products with the greatest development potentials in the mobile internet era.[8]

Social media in China is a vast electronic landscape (see Figure 2 above), and micro-blogging revolves around two Weibo platforms: Tencent and Sina. Tencent and Sina have about 500 million subscribers each, although it is unclear how much the memberships overlap, and how many of the collective roughly one billion registered members are only registered once. It is also clear there is a migration toward Wechat. This trend will almost certainly gain speed as China’s government continues to clamp down on weibo. New Chinese rules on weibo stating that users who send politically incorrect rumors that are viewed more than 5000 times or retransmitted more than 500 times face imprisonment have a chilling effect. That chill also removes a peaceful feedback loop. The figures for the number of weibo users is likely greater than the total number of Internet users for several reasons such as people having multiple accounts, using the services via multiple IP addresses, and also because the overseas Chinese diaspora and others interested in China are also joining those platforms.

The typical Chinese “netizen” is not only absorbed in private or domestic concerns. A significant level of virtual commentary now exists on “core” foreign policy and security issues, much of it highly critical of the central government and its policies. In Table 1, we summarize a selection of such social media “storms” that relate to foreign policy and security issues, including China-DPRK relations and Japan’s military white paper.

It is important to note that some of the nationalist and even xenophobic positions articulated in Chinese popular social media are encouraged by officials or official agencies. For the most part, they are tolerated and only the most virulent, if any, are scrubbed from the system. This serves to buttress the central government’s position in dealing with external adversaries such as the United States, Japan, and even the DPRK. This was evident in the responses to Japan’s defense white paper in 2013 (see Table 1). Typically, however, although some bloggers (often officials in private capacity) support government policy, the vast majority of China’s netizens are critical or even condemnatory of government policy when the case calls for outrage (as in the case of the DPRK arrest of a Chinese fishing vessel, see below).

At issue is the tremendous amount of bottom-up and sometimes lateral pressure on policy makers generated by electronic swarming. That pressure also creates a new type of volatility and lends uncertainty to outcomes. Due to the effects of this new force in China’s foreign policy and security policies, it is critical for external actors, especially civil society, to not only identify and communicate with those people who traditionally were key to influencing these debates, but also, to communicate with social media in China directly in order to inform, temper, and sometimes, propagate the domestic debates from inside to outside of China. We will discuss a conceptual model later in this essay.

TABLE 1: SELECTED SOCIAL MEDIA COMMENTARY ON SECURITY ISSUES, 2012-2013

January 2012: Rumors of DPRK Coup: Chinese netizens mostly dismissed as “implausible” rumors of a DPRK coup d’état.

February 2012: Rumors of North Korea Assassination Attempt: PRC netizens discussed a rumor that DPRK leader Kim Jong-un was assassinated in his house in Pyongyang.

April 2012: PRC-DPRK Account Gains Following: Pro-North Korea “Today Korea” account opened on Sina Weibo and attracted over 100,000 followers in only a few days

September 2012: Anti-Japan Protests Become a Hot Topic: Anti-Japan protests related to Sino-Japanese territorial disputes over the Senkakus (Diaoyu Islands in China) discussed on Chinese social media.

April 2013: PRC Netizens Report Military Mobilization on DPRK Border; Oil Aid Unaffected: Despite foreign media reports that China suspended crude oil exports to the North in February, Sina Weibo user “Chaoji Da Benying” said that the operation of the oil pipeline from Dandong to North Korea appears to be undisrupted (1 April). “RyanEquilibrium” claimed seeing DPRK “officials” at an oil measurement station in Dandong, who the user said visit the station every month (1 April). • User “mickeymouse” (note that a user on a Chinese system chose to adopt a Western persona) said in a posting on local forum Dandong Fengyun Wang (丹东风云网)that Dandong Customs officials turned a blind eye to oil products carried by trucks “travelling to North Korea daily” (24 March).

May 17-24 2013: DPRK Seize Chinese Fishing Boat: PRC netizens commented on the May 5th seizure by the DPRK of a Chinese fishing boat and its crew. It was the second time in one year that DPRK seized a Chinese fishing boat. More accurately, it was the second time China made public that DPRK seized a fishing boat. There are indications DPRK seized more fishing vessels. Most condemned the DPRK for the abduction, calling the country “ungrateful.” Noting that it is not the first such seizure, Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of Huanqiu Shibao (环球时报) Global Times, called the captors “a bunch of scoundrels” and suspected that the DPRK has its own people in Dandong. (Sina Weibo, 20 May). Retired Major General Luo Yuan, vice president and secretary general of the China Council for the Promotion of Strategic Culture, expressed anger over the incident, saying the DPRK had “gone too far” (Sina Weibo, 20 May). Responding to the release of the fishing boat and its crew, PRC diplomat nicknamed “Vegetarian Cat 2011” opined that there are “no winners” both sides are “losers” (Sina Weibo, 20 May).

When DPRK special envoy Choe Ryong-hae arrived on May 22nd, soon after the fishing boat was released, most Chinese rejected the visit, calling the DPRK “shameless” and “ungrateful.” QQ Weibo user “Wang Yong Liang” called the DPRK “shameless,” criticizing Choe for “having the nerve to come and ask for money” and urged China to stop giving aid (QQ Weibo, 23 May). Sina Weibo user “Zheng Yu 2011” asserted that China should “stand firm” and show its “determination to denuclearize the DPRK.” (Sina Weibo, 23 May). Calling the DPRK an “ungrateful wolf,” user “TimeU, Qing Tu Yin Xu” maintained that the DPRK is “useless” to China and that Choe only visits China to “seek protection and food” (Sina Weibo, 23 May).

June 2013: PRC Netizens Discuss Japan’s Defense White Paper: PRC microblogs Sina Weibo and QQ Weibo, posted 11,938 and 7,800 comments on Japan’s defense white paper. Japan’s defense white paper accused China of attempting “to change the status quo by force based on its own assertion.” Bloggers on Jiefangjun Bao’s (解放军报) PLA Daily – an official Chinese military publication) official weibo criticized Japan for “playing up the China threat” and “creating tensions and conflicts” (QQ Weibo, 10 July). Most condemned Japan for its ambitions and said its “ultimate goal” is to “break away” from the United States. Sina Weibo user “Bu Jian Zheng,” for example, maintained that Japan is only “using” the United States and that it is “biding its time to stab the United States in the back” (Sina Weibo, 10 July). Sina Weibo user “Qiao Xin Ting Xue” urged China to “speed up” its process of bolstering the military (Sina Weibo, 10 July).

July 2013: PRC Microbloggers on Li Yuanchao’s Presence in DPRK’s Armistice Day Events

While some microbloggers such as Sina Weibo user “Di Daren” (Sina Weibo, 29 July) argued that in view of Japan’s threat, China must ally with the DPRK, others such as Sina Weibo user “nta” criticized Chinese Vice President Li Yuanchao’s 25-28 July visit to the DPRK to mark the 60th Korean War Armistice anniversary for “aiding a tyrant to do evil” and “assisting the Kim dynasty to prolong its dictatorship” (Sina Weibo, 27 July). Another QQ Weibo user called “Blue” wrote, “Wallowing in the mire with the DPRK! Why do we have to commemorate the most terrible war that should not have happened?” (QQ Weibo, 27 July)

Sometimes, the virtual commentary directly punctures the cultural meta-narratives and legitimacy of existing central government foreign policy. The virtual commentary also resonates widely within segments of the e-literate elites, shaking the ideological foundations of policy lines, and in some instances, threatening to sweep away (or at least severely erode) whole policy lines. China’s alliance and support for the DPRK is a case in point. In Table 2, Chinese social media commentary on the DPRK’s extraordinary nuclear threats against the United States and South Korea in March and April of 2013 was unreservedly critical not only of the DPRK (“a dog that bites the ones who feed it”) and the United States (which deserves to be “attacked by other countries”), but also of China itself (the crisis is “entirely of China’s own making” and the result of China’s “conniving behavior” toward the DPRK).

Thus, high-level officials, especially younger leaders who are highly connected to the Internet and to social media, are alert to early signs of “Internet events” (“public events with the participation of netizens – which are entities or persons that are actively involved in online communities – expressing their opinions or giving comments.”[9]) like these that activate Chinese super-bloggers (those with more than a million followers) and stimulate social media to swarm all over an issue. The presence of their own avatars and virtual names is an important status symbol of modernity and leadership to many of the younger officials who participate in social media. Due to the pervasive nature of connectivity, this virtual presence includes officials in provincial governments with international borders (for example, Liaoning Province which borders North Korea), and those in major trading cities exposed to flows to and from the external world of people, trade, finance (for example, Dandong which is directly across the watery border from Sinuiju, North Korea), etc—not just those at the center of power in Beijing.

A more cynical view is that China sends out test inflammatory messages and themes to draw out those who may stray from the Party Line. Those individual accounts who self-identify as straying from the approved discussion limits makes tailored surveilling and curtailing of social media more efficient.

Exactly how social media plays out in the power dynamics of foreign policy and geo-strategic decision-makers is opaque. Those in the academic and policy advisory inner circles often float a trial balloon (抛砖引玉, “Throw out a brick to attract jade”) by mentioning a concept or proposal. If the concept is too controversial or if it unclear how the idea might be received they may say it was from a foreign source. The risk posed by raising new ideas can be diluted even further by qualifying a posting as relaying the idea attributable to another party, especially one from overseas.

Conversely, even at the Central Party School, younger officials have been observed proudly reporting their aggressive, even emotional stances on various high profile issues that they have expressed via social media—their private voices publicly venting views that are clearly at odds with official policy. These statements are often made in the presence of older and traditional charismatic leaders from an earlier era who carry unquestionable organizational and political authority. Undoubtedly this dissonance has many dimensions. At times, the younger official’s avatar may be using an international posting as permission to discuss an issue in China in order to set agendas. An official’s private avatar may be voicing a trial balloon in policy terms, testing the waters or pushing an alternative policy on highly visible social networks viewed by the personal networks of younger officials connected to the official by cohort, mentor, origin, or family ties. In some extreme cases, these positions may be encouraged by a silent opponent in order to push an official across a line of permissible versus non-permissible contention, in order to trap the official as part of a line struggle within or across agencies, and between policy currents.

At some point, the party leadership will find officials who become serious players on social media to be a potential threat to their organizational power in the form of personality cults and populist demagoguery. Therefore, unsurprisingly, the Chinese Communist Party and media entities such as Xinhua and People’s Daily have social media accounts in China, but senior leaders do not. These machinations also likely played a key role in China’s recent decisions to enforce real name registration, and also to criminalize spreading rumors via social media that are re-sent more than 500 times or viewed more than 5,000 times.[10] Chinese authorities realized that there was a powerful contradiction which cannot presently be solved in a classically dialectic manner using the tools presently available to China’s government. The short term solution though is to use approximately two million people to monitor the traffic and trends.[11] We infer that just as China’s government is changing its approach to responding to these new forces, so those who deal with China from outside should change their approaches also.

Table 2: NETIZENS RESPOND TO DPRK NUCLEAR THREATS, APRIL-MARCH 2013

April 4-11, 2013, PRC netizens were observed to comment on the DPRK’s recent warning of a “merciless, sacred, retaliatory war” against its neighbors and the United States…

As of April 11, 2013, approximately 2,389,173 and 1,347,200 “weibos” (microblogs) were posted on the popular Sina Weibo and QQ Weibo (respectively) discussing the DPRK’s threat to wage what the DPRK KCNA termed a “merciless, sacred, retaliatory war” on its neighboring countries and the United States.”

Lu Shiwei, a senior researcher at the Institute of Modern International Relations at Tsinghua (Qinghua) University, contended that “the US sanctions, pressures, isolation against the DPRK for the past few decades” are “one of the root causes of the conflict on the Korean Peninsula” (Sina Weibo, 10 April).

Yue Gang, renowned military commentator and former colonel of the PLA General Staff Department, opined that the United States has “gone too far” and that “its losses will outweigh its gains” if it decides to enter war “with a country that possesses nuclear weapons.” Conjecturing that the United States and the ROK will make certain compromises with the DPRK, Yue maintained that the DPRK will become the “big winner” if there is no war launched in the end (Sina Weibo, 9 April).

Military expert Zhao Chu asserted that the reason the DPRK has managed to stay “safe” since the Cold War is not due to its nuclear weapon capabilities, but because of 1) the complicated situation on the Korean Peninsula, 2) the ROK’s inability to reunite with the DPRK, and 3) former US President George W. Bush’s focus on fighting terrorism (Sina Weibo, 8 April).

Many PRC netizens commented that China is responsible for the current crisis on the Korean Peninsula.

QQ Weibo user “Du Qiu” said China has “raised a dog that bites the ones who feed it,” adding that the DPRK will “destroy” China’s “stability” and the “good progress of the country’s reform and opening up” (QQ Weibo, 10 April).

QQ Weibo user “Zhai Cheng Feng” condemned China for having a double standard, as it “did not say a word” when the United States and the ROK were conducting military drills near the DPRK, but then attacked the DPRK for launching a nuclear test (QQ Weibo, 10 April).

Sina Weibo user “Cool Is My Trademark” argued that the current Korean Peninsula crisis “has much to do with China’s conniving behavior” toward the DPRK. Another user “ItsRyaning” maintained that the crisis is “entirely of China’s own making” (Sina Weibo, 10 April).

Other PRC netizens, however, blamed the United States for the current situation.

QQ Weibo user “Stroll in Rainy Night” said while it is “necessary” for the DPRK to “put up a front,” it is “impossible” that the DPRK will conduct a missile launch unprovoked. He then urged people to “stop chastising only the DPRK,” which behaves the way it does because it has been “pushed into a corner by the United States” (QQ Weibo, 10 April).

Sina Weibo user “Mini Young Melon” asked why everyone points their finger at the DPRK but not at the “culprits” — the United States, Japan, and the ROK (Sina Weibo, 10 April).

Calling the United States a “nation that does not know how to respect other countries,” Sina Weibo user “Tian Tian Xiang Shan Bu Yong Xue Xi” blamed the United States for the crisis, and said it deserves to be “attacked by other countries” (Sina Weibo, 10 April).

Micro-blogging on matters related to the DPRK is fairly continuous these days. For example, the possible restart of the North Korean graphite-moderated reactor in mid-September 2013 prompted Weibo users to suggest that the DPRK sought either assistance or attention by leveraging the West with the implicit threat represented by the reactor. Some mocked Kim Jong-un as “lonely.”[12] Beijing-based TCBFLW observed: “If the US can’t knock out Assad, how will it take care of Kim Jong-un?”[13] Li’ang_Sikete (Sichuan) notes: “This creates an excuse for the US to strike.”[14] in Shanghai cautions “Just you watch—once the curtain has fallen on Syria, North Korea will immediately take the stage.”[15]

Sina Weibo microbloggers on North Korean subjects tend to fall into three distinct categories. The first are official Chinese media correspondents who file hundreds of posts from Pyongyang. Xinhua correspondent Du Baiyu on her Sina Weibo account named “Du Xiaobai covers events on-the-spot. On July 25, 2013, for example, she posted a report that Kim Yong-chun, vice chairman of the DPRK Central Military Commission, hosted a banquet for PRC war veterans.[16]

Many Chinese experts on North Korea from government-affiliated think-tanks—the second category–more or less follow the official line on the DPRK. Mei Xinyu, for example, from the Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation (Ministry of Commerce) often comments on the DPRK economy and trade with China on his Weibo account. On June 8, for example, he posted on coffee shops and development in Pyongyang as signs of the North’s “economic revitalization.[17]

In the third category—unaffiliated individuals with commercial or other relationships with the DPRK—generally pro-DPRK views are expressed. One, “Writer Cui Chenghao,” is particularly well-known with 1.6 million followers in November 2013. He describes himself to be trading across the border. His pro-DPRK blogs tend to be melodramatic, often prove to be inaccurate, and generally anti-American.

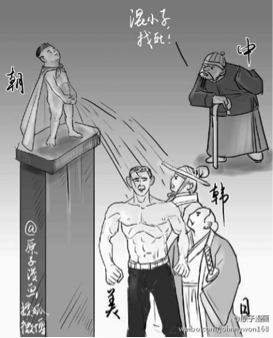

Much on-line commentary by Chinese citizens falls outside these categories, however, and simply expresses trenchant commentary on current affairs. In April 2013, for example, cartoonist Johnny Won posted “Impish Overlord,” to Sina Weibo, showing Kim Jong-un atop a pedestal, costumed with a cape. He is peeing on a muscular United States, a samurai warrior Japan and a South Korea clad in traditional formal civil clothes. Off to one side, China leans on its cane and says, “Stupid child, you’re asking for death.”

(Source: “Impish Overlord,” posted at Comic China, China Media Project, University of Hong Kong, at: http://cmp.hku.hk/2013/04/11/32581/)

Exactly how these contentious and often contradictory views relate to high-level official perspectives on the DPRK is unclear. In our observation, official perspectives on the DPRK at the level of the central party, military, and agencies, tend to fall into three positions: a) senior leaders, who view the DPRK as a long-term liability, even adversary, but a problem to be managed jointly in the short-term with the United States—if only they can find common cause; b) the administrators of daily transactions and active relationships with the DPRK in many channels and dimensions, who tend to be pragmatic and search for short-term solutions; and c) within the military, the Old Guard which is pro-DPRK for historical reasons as allies in combat, but increasingly concerned that the DPRK is shedding its revolutionary ideology and adopting erratic, even bizarre garb under Kim Jong-un, versus, the New Guard of rising officers who are pro-DPRK on the basis of strident anti-Americanism.

Thus, at least some of the military appear to be voluble on the DPRK issues in Sina Weibo, expressing contrasting views. After the DPRK’s February 12, 2013 nuclear test, for example, Major General Luo Yuan (CPPCC National Committee, China Military Science Society, PLA Strategy Culture Promotion Association) condemned Pyongyang saying it threatened China and advocating “moderate sanctions” (24 February). Conversely, Dai Xu (Hainan Institute for Maritime Security and Cooperation, National Defense University) castigated the United States for “making use of the Korean Peninsula tension to strategically shift its military deployment to the east in an attempt to contain China” (12 April) while Guo Songmin (writer, ex- PLA Air Force) claimed that the DPRK’s test provided “security” enabling it to focus on economic development (10 July).

CHINESE SUPER-BLOGGERS

The massive reach of super-bloggers in China should not be under-estimated. In July 2013, for example, ten Chinese super-bloggers were invited to tour and blog in South Korea—trips that undoubtedly required central government approval.[18] The top two of these ten bloggers have a combined social media following of 23 million people in China. If only half of their readers read their posts, then 11.5 million active followers were exposed to their posts from South Korea. If we assume just two percent of their active followers then shared these messages with their friends and followers, then the super-bloggers Korean posts may have reached a further 1.1 million readers (assuming 500 friends/followers for each person who reposted the original super-bloggers post). Just two super-bloggers can realistically reach 13 million netizens in China, another demonstration of the rapid increase in information velocity. The information travels far more rapidly than before and is directed from the super bloggers to people and challenges the cultural meta-narrative that the Party controls all.

EXTERNAL INFORMATION

A vast reach can also be prompted by external postings circulated inside China. For example, Nautilus’ Special Report on the large-scale uptake of cell phones in North Korea (On the Cusp of a Digital Revolution[19] by Alexandre Mansourov) went viral on social media in China. On one site[20], the following conversation (summarized after translation) occurred:

A person posted a brief excerpt of the Nautilus report “On The Cusp Of A Digital Revolution”. She, her friends, and others then chatted about it. The first comment was “I had no idea there were so many cell phones in North Korea”. The person’s friends joined the conversation and started wondering how people can afford cell phones when they can’t eat (a clear indicator at least some average Chinese understand North Korea is experiencing a famine). One remarks that a structure is determined by its foundation (an allusion that North Korea is only as strong as Kim Jong-un and an implication he is not strong). And another netizen disparages “Fat Kim / Fat Gold” (In Chinese language the character for “Kim” is ”gold”. “Fat Kim” is a commonly accepted, though manifestly impolite, reference to Kim Jong-un, North Korea’s ruler).

Exactly what exposure triggered this netizen interest is unknown. The essay was re-posted by the (official) China Arms Control and Disarmament Association on their website on November 4, 2011[21] but social and digital news media did not begin reposting it en masse until November 21st. Social media interest may have been triggered by international media coverage that mentioned the report on November 21st (a Reuter’s report[22] for example). Perhaps it was domestic digital news coverage that morning (at 163.com for example[23]). The distinction in these cases whether the news media reporters followed the path of social media swarming around the topic, or social media were set off by the news media is unclear but unimportant.

What is evident is that an external report triggered social and news media storms that fed off each other, resulting in massive coverage of a topic highly salient to a sensitive external relationship between China, North Korea, South Korea, and the United States. Consequently, “Internet events” on social media and the Internet have profound bottom-up and lateral potential to pressure the central government officials and agencies to realign provincial or local government policy, scapegoat a specific individual, company, or agency, etc. in order to preserve the meta-narrative of legitimacy and power of the central government or its provincial agents. For example, in the blame game that ensued after the horrific July 2011 crash of a high speed train in Wenzhou city in Zhejiang Province, Beijing officials used the Internet to put the onus on lax local government and the line agencies responsible for the accident, and kept the focus away from the central leadership.[24]

SOCIAL MEDIA AND POLICY-MAKING

One can only conjecture exactly how these information vectors based on virtual, bottom-up citizen mobilization intersect with the personal, intimate politics of networked patronage and mutual obligation at the center. One answer is to argue that such influence can only be inferred indirectly from observed effects, always subject to the problem of counter-factuality (what else might have changed or be influential, which can never be known in full). Another answer is to use either formal or informal agent-based modeling to simulate the true complexity of this interplay, and then interpret the patterns that result from the specification of the agents and their decision rules.

For example, using agent-based modeling, Tan, Li and Mao simulated two public Internet events in China in 2010, the Synutra baby milk powder scandal, and the conflict between Qihoo and Tencent software companies over privacy protection software.[25] In both cases, Internet events erupted resulting in hundreds of reports, scores of thousands of comments, and ultimately, government intervention to resolve both situations.

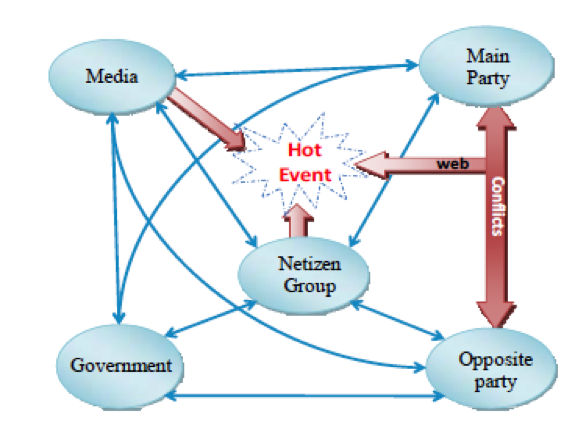

The model specified five entities, viz, “main party, opposite party, netizen group, media, and government. The main party “refers to the people or the group who initiate a hot event.” Those who study China will recognize “hot event / 热点事件” as any triggering event and sometime hashtag. China’s Xinhuanet even has a page by that title. Presumably having a central location allows all parties a central clearing house and makes monitoring “hot events” a little easier.[26] The opposite party is “the group having conflicting interests regarding the event with the main party.” Their actions (in the form of responses) usually trigger the Internet event. The netizen group are the “netizens who are associated with the Internet event via online participation.” Media refers to traditional mass media. Government is assumed to be an intermediary in some respects in this model, rather than the primary target of netizen ire.

Each of these five parties in the model has one or more “belief states” (for example, the belief state of government is concerned with its own credibility) that is affected by the interaction during the Internet event. Each party has a set of possible actions. Government actions, for example, are to “get-involved, judge-winner, appeasement, award, punishment and no-response” each with an associated estimate intensity and target for their actions. Interactions between the entities are governed by rules that specify how the actions of one entity influence the others. Thus, when conflicts increase between the main and opposite party, media and netizen concern also increases. Actions by other parties such as netizen criticism also increase concerns of all parties. Often, negative actions (in the case of netizens, these include praise, donate, digitally broadcast or suppress, and criticize) have more influence than positive actions, which is reflected in the models.[27]

(Figure 3: Agent-based model for netizen-centered Internet events in China

Source: Z. Tan, X. Li, W. Mao, “Agent-Based Modeling of Netizen Groups in Chinese Internet Events,” Quarterly SCS M&S Magazine, (journal of Society for Modeling & Simulation International) April 2012, p. 40, at: http://www.scs.org/magazines/2012-04/index_file/Articles.htm)

Tan, Li and Mao used a standard agent-based modeling tool (Repast) to represent these entities, states, and interactions and compared simulated their interaction over time with actual social media data mined from postings. In the case of the Synutra baby milk, the skepticism of the netizens clearly contributed to the media attention and to eventual government intervention after official inaction and cover-up, forcing the Health Ministry to intervene in response to bottom-up netizen rage.[28] The simulated pattern of interaction over time closely (but not always) matches that of the actual data—as occurs in the modeling to the Qihoo and Tencent conflict. Of particular interest is the way and speed that social media and mass media coincide in putting the main party in the Internet event and thereby also placing the government, in a negative limelight, thus forcing an official response in order for the government to reinforce the meta-narrative of government control.

In a foreign policy or national security context—especially one involving high levels of secrecy such as nuclear weapons policy, deployments, threats, delivery systems, or outcomes of use, a relatively simple five agent model such as that above may be difficult to specify—but not impossible. In some cases, the object of ire may be a local embassy of a target main group (for example, as occurred with protests against Japan in China in recent years). However, we are not aware of any agent-based modeling of the interaction of social media with elite perceptions, views, and policy-making in China at this time. However, Dr. Jessica Chen Weiss provides another model for analyzing public protests and their impact on foreign policy in China. China’s government likely balanced several factors in their decisions about dealing with protests. The model assumed governments calculated and made trade offs in a rational manner. Governments could encourage and allow protests – which always runs a risk of getting out of control. Or they could pre-empt and avoid a protest at a possible cost of appearing unpatriotic to their people. Under these assumptions, it would appear that Chinese decisions to allow or stop domestic protests were allowed because they served diplomatic bargaining leverage purposes.[29]

Nonetheless, we are always free to infer the mechanisms and processes by which social media influences officialdom and vice versa, starting with the fundamentals and accounting for the contextual and structural parallels between domestic Internet events and official policy with foreign policy and national security concerns. As noted earlier, contending Chinese policy currents that transect China’s pyramid of power composed of the party, military, and line agencies confront a set of “master narratives” about domestic and international issues that frame modern China. In terms of the legitimacy of power (always a sensitive topic) at the center, these policy currents propose different approaches to the primary issues of the distribution of wealth and power, equity and social justice, political reform and democracy, ecological integrity, the fate of the oppressed minorities. When such issues explode into Internet events, they provide an opportunity for central authorities to monitor local developments, to direct ire against local agencies or to promote local solutions to concrete local social problems. Bottom-up reporting of local events combined with expression of local resentment are amplified by social media into Internet events, and enable the center to be responsive to social grievances, in a long tradition of petitioning the center for redress against local abuses of power and authority.

The Internet and social media thereby become a means whereby Chinese citizens can participate in deliberations within China’s rigid political system rather than requiring structural changes to create a democratic, pluralist system. The latter may not look like a classic Western democracy, but it is a possible “dialectical” response which allows China’s Party to adapt and maintain its legitimacy by managing an otherwise “antagonistic contradiction” between itself and its virtual civil society.

In some of the key concepts that legitimate Communist Party rule such as restoring China’s rightful place in the world,[30] national security and foreign policy concerns loom large. In the case of North Korea, for example, the explosion of social media commentary on DPRK issues and its sensitivity to the latest rumors, as well as field reporting along the border, included at various times strongly stated views concerning China’ diminished prestige, its (lack of) ability to impose its will on its small but nuclear-armed ally, and its passive role relative to the United States in coercing the DPRK to capitulate on nuclear and other issues. This time, the social media commentaries coincided with a policy line struggle that continued for months as various entities in Beijing considered whether to demote the DPRK as full ally to a marginal and possibly negative relationship in the context of regional and global geo-strategic considerations.[31]

In this instance, social media not only criticized core tenets of Chinese policy towards the DPRK such as emphasis on slow reform before regime change, but focused directly on previously taboo topics for public discussion such as nuclear weapons arising from the DPRK’s campaign of nuclear threats against the United States and its allies, and even, some admitted, directed against China itself. The breadth and depth of this discussion were summarized in Table 2. Similar sentiments and debates to those in social media were observed within the foreign policy and security elite at the center. In some cases, officials used the stereotype of “ugly North Koreans” to whip up nationalist sentiment (as in the fishing boat incident). But in general, Chinese virtual opinion and much of the central officialdom have shifted their emotional and political loyalties away from an alliance born in the blood of 900,000 Chinese casualties in the Korean War towards merely tolerating North Korea but slouching toward eventual drift away from the North Koreans. To be clear, the official policy is that the relations between the two countries are “normal” as opposed to previous characterizations of a “special” relationship.

There are also generational fault lines: those who were directly involved in the Korean War as Chinese People’s Volunteers fighting in Korea have been out of power for almost a decade, while the e-literate elites are present at most levels of China’s government and account for almost all provincial and municipal level leaders. The China-DPRK alliance holds for the younger generations, but is strictly based on brutal self interest without regard to emotional and ideological ties forged during the Korean War. The two generations also represent digital fault lines: digital outsiders, digital immigrants and digital natives.[32] Those who fought in the Korean War are generally digital outsiders with no social media presence whatsoever. The transitional generation roughly defined as grandchildren of those who fought in the Korean War are digital immigrants. Almost all of China’s leaders at the municipal level and below are digital natives. China’s political leadership is groomed by serving in successively higher levels of responsibility. Today’s municipal leaders are also twenty to thirty years away from being in China’s most powerful positions – and they cannot relate to most North Koreans.

POLICY CURRENTS AND BOUNDARIES

The boundaries where social media form flash floods that feed into tributaries that in turn, merge into slower moving policy currents down-river, are chaotic and indeterminate. Sometimes social media will be driven by central government policies, statements, and actions. In such cases, they accelerate a bottom-up or sideways push effect. In other instances, social media will amplify pressure building in a policy current to the point that it can burst through resistance and lead to change instigated at the highest level, sometimes by replacement of senior officials. The ultimate flood—a burgeoning social movement demanding democratic pluralism—faces a massive dam—the Party. But all sorts of billabongs, holding reservoirs, spillways, and other control devices exist to forestall the day when virtual deliberative discourse would contribute to sweeping away the dam represented by the Party’s monopoly on political power. Since domestic politics always trumps foreign policy, it is important to understand social media effects in this domestic context.

Overall, the always shifting boundaries of the chaotic interplay between personalized, networked politics at the center with massive social media mobilization at the distal ends increases the volatility and turbulence of policy making processes, not least because social media accelerates propagation of errors, thereby increasing uncertainty. Top-level officials and political figures are driven by this dynamic to seek ever-broader social and political bases in order to share risk and diversify their sources of legitimacy–and to demonstrate the breadth of their support.

Already observable trends in social media may affect the interaction processes. Chinese social media have begun to establish “rumor refutation” groups (such as (weibo piyao 微博辟谣, in 2010). Others have created “self purification” (ziwo jinghua自我净化) networks dedicated to exposing fake or false information, in part to offset the amplification by social media of erroneous field reporting or rumor propagation associated with Internet events.[33] This self-corrective feature of social media combined with more reflective, less event-driven postings may herald the emergence of a mature civil society in China able to address national security and foreign policy issues in ways that are more amenable to uptake and to policy reformation at the center.

Obviously, in the case of weapons of mass destruction, we do not want to wait for detonations or footloose nuclear materials to activate an Internet event and thereby, social media. Indeed, at such a moment, the Internet may be shut down altogether. Rather, in the case of “routine” security threats that arise from non-state sectors in the first place—such as criminal networks moving drugs and trafficking in humans—social media may play an important supplementary role to the state and market entities in terms of “situational awareness,” self-surveillance, and direct regulation of behavior in time-critical situations. The key will be to find ways to cross over from closed official deliberations to public disclosure and commentary that increases public understanding and societal situational awareness of key aspects of the risk of non-state nuclear weapons proliferation.

CONCLUSION

We dwelled on the social media dimension of communicating in China in order to make the case that in addition to ensuring that information services reach traditional elite Internet users, another essential goal should be make information services increasingly accessible to China’s social media content leaders who are proactive in leading contentious debates, are often critical (in the classic sense of the word, not the pejorative sense) and reflective thinkers, and whose voices, often unknown in the West, deliver trenchant and influential commentary on foreign policy and security issues in China.[34] This can be achieved by increasing the channels for their views to be heard in the West as well as facilitating inter-Chinese conversation.

If we are correct in the transformative, game-changing nature of the rise of social media and its potential impact on foreign policy and security policymaking in China, then we believe a few of the many possible implications for external civil society organizations are: a) they should publish their material in emails, not just post them on the Web. Some websites, and therefore their content, are blocked and unreachable from inside China. But external emails almost always reach producers of social media a; b) that as much as possible of the key debates in China on foreign policy and security affairs on Chinese social media be distributed outside of China. Most debates on social media rage with almost no external visibility. ; c) that more external materials sent via email and posted on the Web are produced in Chinese, in addition to English and other languages common to the Chinese-language diaspora such as Korean, Japanese and Russian languages, to increase their accessibility to the largest single public on the planet. Already, some embassies based in China have begun to post on weibo. Some examples include the United States (713,000 fans), the United Kingdom (310,000 fans), Japan (232,000 fans), South Korea (140,000 fans), Australia (108,000 fans) and Russia (91,000 fans). Of course, weibo is meant to be interactive so there are also messages directed to the Embassies.

Social media in China allows nascent civil society to have a voice, albeit only a limited voice, in the expression of values and views China incorporates into its foreign and security policies. Although still highly constrained, commentators using social media in China may play an important supplementary role to the state and market entities in terms of “situational awareness,” self-surveillance, and direct regulation of behavior in time-critical situations that arise from non-state populations in the first place—such as criminal networks moving drugs, trafficking in humans, or smuggling nuclear weapons related knowledge or items. Many of the leaders of Chinese social media, including elite security analysts and officials, are already networked with external parties, and receive constant infusions of information and analysis in spite of the Great Firewall.[35] How these new players affect China’s foreign policy and security calculus is a critical variable in governing the future security challenges that will confront its neighbors and competitors. In this regard, civil society networks that communicate directly and effectively with social media in China may be far more influential in helping China shape its policies than governments, especially in the arena of security conflicts where governments are at loggerheads.[36] These networks provide important channels for communication to prevent crises. When crises occur, they can also play important roles in crisis management by moderating online responses, extending the amount of time before a “hot issue” reaches crisis level, providing leaders more time and more options to resolve a situation and resorting to dialog rather than threats of military force.

III. References

[1] K. Brown, “China: What We Think We Know is Wrong,” Open Democracy, May 15, 2013, at:

http://www.opendemocracy.net/kerry-brown/china-what-we-think-we-know-is-wrong

[2] Xiaowen Xu ascribes these categories to Guobin Yang,The Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online, New York: Columbia University Press, 2009, p. 13.

[3] See, for example, “Chinese Nuclear Arms Control and Disarmament: Principal Players and Policy-Making Processes,” James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, 2009, at: http://www.cns.miis.edu/opapers/op15/chart_11x17_china.pdf For a distinctly written by and for Chinese view see: Xufeng Zhu and Lan Xue, “Think Tanks in Transitional China”, Public Administration and Development, Vol 27, 2007. For a European overview of Chinese foreign policy think tanks see: Pascal Abb, “China’s Foreign Policy Think Tanks: Changing Roles and Structural Conditions”, German Institute of Global and Area Studies, No 213, January 2013.

[4] China Internet Network Information Center, Statistical Report on Internet Development in China, January 2013,at: http://www1.cnnic.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/

[5] Ibid, pp. 4-5.

[6] China Internet Network Information Center, “The Internet Timeline of China,” 2012, at:

http://www1.cnnic.cn/IDR/hlwfzdsj/201305/t20130508_39415.htm

[7] China Internet Network Information Center, Statistical Report, 2013, op cit, pp. 18, 36.

[8] China Internet Network Information Center, Statistical Report, 2013, op cit, p. 47.

[9] Z. Tan, X. Li, W. Mao, “Agent-Based Modeling of Netizen Groups, op cit, p. 39.

[10] 人民网,“两高:网络诽谤信息被转发超500次或判刑3年 “,2013年 9月9日, at http://opinion.people.com.cn/n/2013/0910/c369011-22866658.html

O. Lam, “Hundreds Arrested for Spreading ‘Rumors’ on China’s Ideological Battlefield,” Global Voices Blog, September 5, 2013, at: http://advocacy.globalvoicesonline.org/2013/09/05/hundreds-arrested-for-spreading-rumors-on-chinas-ideological-battlefield/

[11] BBC News China, “China employs two million microblog monitors state media say,”

October 4, 2013 at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-24396957

[12]领航001网军事频道(Military Channel Pilot 001, Linghang001wangjunshipindao),

at: http://e.weibo.com/u/3698947607

[13] TCBFLW (TCBFLW): at http://weibo.com/u/1457368343

[14] 里昂_斯科特(Li’ang_Sikete): at http://weibo.com/laodaguo

[15]左边你千万不要觉得我的名字太长 (The left should never think my name is too long, Zuobianniqianwanbuyaojuedewodemingzitaizhang): at http://weibo.com/u/3217910737

[16]杜筱白 (Du Xiaobai): at http://weibo.com/rainyinci

[17]梅新育(Mei Xinyu): at http://weibo.com/meixinyu

[18] “Chinese ‘power microbloggers’ to visit S. Korea this week,” Yonhap News Agency, July 1, 2013, at: http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/yonhap-news-agency/130701/chinese-power-microbloggers-visit-s-korea-week

[19] A. Mansourov, North Korea on the Cusp of Digital Transformation, NAPSNet Special Report, November 1, 2011, at: https://nautilus.org/publications/napsnet/reports/page/7/#axzz2bJek6h6a

[20] The exchange is found in Chinese at: http://tieba.baidu.com/p/1292015149

[21] At their website, at: http://www.cacda.org.cn/a/ENGLISH/World_Views/2011/1103/1093.html

[23] At, for example, http://news.163.com/11/1121/11/7JCM79DL00014JB5.html

[24] Xiaowen Xu, “Internet Facilitated Civic Engagement in China’s Context: A Case Study of the Internet Event of Wenzhou High-speed Train Accident,” Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Columbia University, Master of Arts, Thesis, December 2011, unpaginated, at: http://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:143148

[25] Z. Tan, X. Li, W. Mao, “Agent-Based Modeling of Netizen Groups in Chinese Internet Events,” Quarterly SCS M&S Magazine , (journal of Society for Modeling & Simulation International) April 2012, pp. 39-45, at: http://www.scs.org/magazines/2012-04/index_file/Articles.htm Tan et al refer to Tecent, but the proper name

(from the website http://t.qq.com/) in English is Tencent, which is used here instead.

[26] Xinhuanet, 热点事件(Hot Events)http://www.xinhuanet.com/society/rdsj.htm

[27] Z. Tan, X. Li, W. Mao, “Agent-Based Modeling of Netizen Groups, op cit, pp. 40-42.

[28] Z. Tan, X. Li, W. Mao, “Agent-Based Modeling of Netizen Groups, op cit, pp. 42-43.

[29] Jessica Chen Weiss, “Authoritarian Signaling, Mass Audiences, and National Protest in China” International Organization Vol 67, Issue 1, January 2013, at: http://pantheon.yale.edu/~jcw74/Weiss%202013%20IO%20Authoritarian%20Signaling,%20Mass%20Audiences,%20and%20Nationalist%20Protest%20in%20China.pdf.

Jessica Chen Weiss, “Powerful Patriots: Nationalism, Diplomacy, and the Strategic Logic of Anti-Foreign Protest,” Unpublished Ph D Dissertation, University of California, San Diego, 2008.

[30] Monitor 360, Master Narratives Country Report/China, Open Source Center, March 2012.

[31] J. Jun, “Dealing with a Sore Lip: Parsing China’s “Recalculation” of North Korea Policy,” 38 North, March 29 2013, at: http://38north.org/2013/03/jjun032913/

[32] For more on the concepts of Digital generations, see Marc Prensky, “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants”,

On the Horizon, MCB University Press, Vol. 9, No. 5, October 2001)

[33] See Xiaowen Xu, Internet Facilitated Civic Engagement, op cit.

[34] In China, on-line adults fall into the following categories (individuals can be in more than one): creators (40%),

critics (44%), collectors (34%), joiners (23%), spectators (71%), and in-actives (25%). See China Social Media Usage, Resonance, at: http://www.resonancechina.com/2010/05/11/china-social-media-usage-statistics/chinasocialmediausage/

[35] In China, on-line adults fall into the following categories (individuals can be in more than one):

creators (40%), critics (44%), collectors (34%), joiners (23%), spectators (71%), and in-actives (25%).

See China Social Media Usage, Resonance,

at: http://www.resonancechina.com/2010/05/11/china-social-media-usage-statistics/chinasocialmediausage/

[36] J. Melissen, “Concluding Reflections on Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in East Asia,” in J. Melissen, S.J. Lee, ed, Public Diplomacy and Soft Power in East Asia, Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2011, p. 261.

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSES

The Nautilus Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please leave a comment below or send your response to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Comments will only be posted if they include the author’s name and affiliation.

One thought on “Internet Events, Social Media and National Security in China”