MOON CHUNG-IN

MARCH 6 2020

I. INTRODUCTION

In this paper, Moon Chung-in and Boo Seung-chan provide historical context on the hotlines linking South and North Korea and point to the lessons that can be learned from the decades-long effort.

A podcast with Moon Chung-in and Philip Reiner can be found here

Moon Chung-in is a distinguished professor emeritus of political science at Yonsei University. Seung-Chan Boo is a spokesperson for the ROK Ministry of National Defense. He co-authored this article as a research fellow of the Institute for North Korean Studies, Yonsei University, before he joined the ministry.

The paper was prepared for a Workshop on hotlines held in August of 2020 and convened by the Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, the Institute for Security and Technology, and the Stanley Center for Peace and Security.

It was published originally on December 17, 2020. The original text in PDF may be downloaded here

It is published simultaneously here by Asia Pacific Leadership Network, here by Research Center for Abolition of Nuclear Weapons-Nagasaki University, here by Institute for Security and Technology, and here by Nautilus Institute and is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here.

Acknowledgments: Maureen Jerrett provided copy editing services.

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus Institute seeks a diversity of views and opinions on significant topics in order to identify common ground.

Banner image is by Lauren Hostetter of Heyhoss Design

II. NAUTILUS INSTITUTE SPECIAL REPORT BY MOON CHUNG-IN

HOTLINE BETWEEN TWO KOREAS: STATUS, LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE TASKS

MARCH 6, 2021

Summary

The Korean conflict has been one of the most protracted in the world, lasting more than 70 years. Despite the heightened tension, there was no channel of communication between the North and the South. It was only on September 22, 1971, that the first hotline between the two Koreas was installed at the Panmunjom—26 years after the telephone line between Seoul and Haeju was cut off by the former Soviet army immediately after liberation on August 26, 1945.

Since 1971, a total of 50 lines were open, including a hotline between leaders of the two Koreas as well as military and intelligence communication lines. But North Korea suddenly cut off all communications with the South with the exception of that between the United Nations Command (UNC) and North Korea military. Nevertheless, they proved to be useful tools for confidence-building measures to improve inter-Korean communication, to facilitate exchanges and cooperation, including inter-Korean official talks, and to assist the promotion of humanitarian aid. More importantly, they have served as an effective mechanism for the prevention of accidental military clashes through a timely exchange of information. This paper presents a brief historical overview of hotlines between the two Koreas, examines their present status, and elucidates limitations and future tasks.

1. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The Korean conflict is one of the most protracted ones in the world, lasting more than 70 years. The Korean War, which broke out in June 1950 and lasted for three years with millions of casualties, is continuing with no immediate sign of termination. A precarious balance of power between the two Koreas, with the institutional backing of an armistice regime, has prevented the two Koreas from erupting into major military escalation. Boundaries between peace and cooperation having been blurred, often escalating into overt conflicts, with a lack of confidence-building measures between the two. Pyongyang has persistently rejected Seoul’s offer of mutual notification and observation of military exercises and training. More critically, there were no communication channels. A complete incommunicado between the two heightened the possibility of accidental clashes in the fifties and sixties.

It was on September 22, 1971, that the first hotline between the two Koreas was established at the Panmunjom, 26 years after the telephone line between Seoul and Haeju was cut off by the former Soviet army immediately after liberation on August 26, 1945. At the time, the two Koreas had installed two telephone lines between the South’s ‘Freedom House’ and the North’s ‘Panmungak’ in Panmunjom. They shared the need for communication channels at the first inter-Korean Red Cross preliminary talks held on September 20 of the same year, which was organized to prepare for the inter-Korean Red Cross talks proposed by the then South Korean Red Cross President, Choi Doo Sun. Since then, the channel has played a central role as a regular liaison system for the authorities of the two Koreas under Article 7 of the Inter-Korean Basic Agreement on Non-aggression, Reconciliation, and Exchange and Cooperation, which went into effect in February 1992.[1]

Since the first Korean summit on June 15, 2000, inter-Korean relations dramatically improved from confrontation and antagonism into reconciliation and cooperation. More inter-Korean hotlines were subsequently installed. The inter-Korean and International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) agreements, which were signed in 1997, but not implemented, were instrumental in establishing a direct telephone line between the Incheon International Airport and Sunan Pyongyang International Airport aviation control centers after the 2000 Korean summit. The South’s National Intelligence Service (NIS) and the North’s Department of United Front of the Korea Workers’ Party, which jointly prepared for the 2000 Pyongyang summit, also established a direct communication line to follow-up the implementation of the June 15 summit declaration. Several additional direct communication lines, such as military ones in 2002 to 2003, maritime communication lines between maritime authorities in 2005, communication lines for the inter-Korean joint committee of the Kaesong Industrial Complex in 2013, and communication lines for the inter-Korean Joint Liaison Office were also subsequently installed.

Most notable was the establishment of a hotline for the leaders of the two Koreas in 2018. Two South Korean special envoys, Ambassador Chung Eui-yong, then National Security Advisor, and Dr. Suh Hoon, then Director of NIS, visited Pyongyang to discuss overall developments of inter-Korean relations during March 4-5, 2018. They conveyed President Moon’s desire to establish a direct hotline with Chairman Kim Jong Un, who instantly accepted the proposal. The first historic summit was held on April 27, 2018, and, afterwards, the summit hotline was set up. It was effectively used in arranging for an unofficial summit talk on May 26, 2018. In addition, the two Koreas conducted regular check-ups of communication lines at agreed upon times.

The communication lines between the two Koreas have not been stable, however, because they have been subject to an alternation between suspension and resumption since opening in 1971, depending on changes in inter-Korean relations as well as overall external environments, especially DPRK-US relations. When inter-Korean relations were good, the hotlines operated smoothly, whereas they were cut off when their relations worsened. Nevertheless, they proved to be useful tools for confidence-building measures to improve inter-Korean communication, to facilitate exchanges and cooperation, including inter-Korean official talks, and to assist the promotion of humanitarian aid. More importantly, they have served as an effective mechanism for the prevention of accidental military clashes through a timely exchange of information.

Current Status of the North-South Hotline

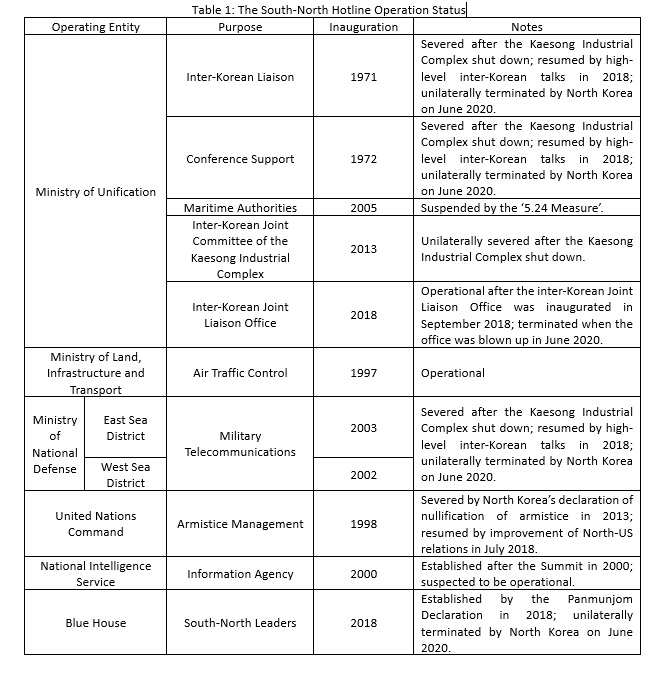

Table 1 is a presentation of the present status of official communications lines between the two Koreas. The Ministry of Unification (MOU), the Ministry of National Defense (MND), the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT), the United Nations Command (UNC), the NIS, and the Office of the President (the Blue House) used to maintain communication lines with their North Korean counterparts respectively. According to various open sources, there have been all together thirty-three direct lines via Panmunjom.[2] Other lines that do not pass through the Panmunjom are nine lines for military communication, six lines for the direct telephone connection of the inter-Korean joint train operation, one line connecting the NIS and the United Front Department, and one summit hotline installed on April 20, 2018, between the Blue House in Seoul and the Korea Worker’s Party Headquarters in Pyongyang. These lines add up to a total of 50 lines.[3] As of 2005, 1,300 optical fiber cable lines existed between the Korea Telecom Corporation’s (KT) Munsan branch and the Kaesong Industrial Complex for the purpose of supporting virtual reunion of separated families and companies operating in the Kaesong Industrial Complex. Of these, about 700 lines were reportedly in operation before the suspension of the Kaesong Industrial Complex on February 10, 2016, immediately following North Korea’s fourth nuclear test on January 6, 2016.

Source: Foreign Affairs and National Unification Committee of the National Assembly, “Policy Materials Prepared for the Opening of the 21st National Assembly,” (Seoul: the ROK National Assembly, 2020), p.274.

The hotlines operated by the Ministry of Unification used to exist in four categories: inter- Korean liaison, North-South dialogue support, maritime communication, the Kaesong Industrial Complex support, and the Inter-Korean Joint Liaison Office. Of these, the inter-Korean liaison lines were the first direct ones between the South and North to be installed in Panmunjom, and dialogue support lines were used to prepare for various inter-Korean official talks. As the North-South Korean Agreement on Maritime Transportation took effect on August 1, 2005, the cable network linking the North-South Korean Exchange and Cooperation Bureau at the Ministry of Unification in Seoul to the Ministry of Land and Maritime Transport in Pyongyang became operational. It was a useful means of communication between the maritime authorities of the two Koreas for issuing permits to ships operating in each other’s sea or sending notices regarding emergency patients.

The three inter-Korean military communication lines were first opened in the West Sea district on September 24, 2002, and another three lines in the East Sea District on December 5, 2003. Both aimed to ensure a safe passage through the South-North Joint Administration Area, as mandated by the ‘Military Assurance Agreement’ signed at the 8th Inter-Korean Military Working Group Meeting.[4] On June 4th, 2004, the Roh Moo-hyun government entered an agreement with the North for the ‘prevention of accidental clashes in the West Sea, suspension of propaganda activities, and removal of propaganda means (e.g., loudspeakers) in the Demilitarized Zone.’ Following the ‘June 4th Agreement,’ three additional lines for military communications were open on August 13, 2005, for the purpose of preventing accidental conflicts in the West Sea.

As inter-Korean relations deteriorated after the inauguration of the Lee Myung-bak government in 2008, the North occasionally suspended these communication lines, making them rather unstable. A major reversal came in 2018. After the adoption of the Panmunjom summit declaration on April 27, 2018, through which leaders of the two Koreas agreed to suspend mutual hostile activities along the Demilitarized Zone and the West Sea, military communication lines in the West Sea were restored on July 16, 2018, and those in the East Sea were also resumed on August 15, 2018. On June 9, 2020, however, North Korea again cut off all military communication lines with the South unilaterally. It was a great setback to inter-Korean confidence-building because they were essential channels for communication to support a safe passage through the South-North Joint Administration Area, notification of no-fly zone entries, prevention of unintended clashes, exchange of information on illegal fishing boats in the West Sea, and exchange of correspondence between military authorities in the North and the South.[5]

The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport also maintained a communication line with North Korea. As noted earlier, the agreement between the two Koreas and the ICAO helped establish two lines for air traffic control between Daegu and Pyongyang. When Incheon International Airport was open on September 9, 1997, Incheon was connected to the Sunan Pyongyang Airport Control Center instead of Daegu. However, these lines monitor and control aircrafts only passing through the Pyongyang Flight Information Region (FIR) and, thus, cannot be seen as communication lines with the North.[6]

The core of the inter-Korean hotline is a direct telephone line that connects the NIS in the South and the KWP’s United Front Department, a counterpart of the NIS that engages in intelligence collection and covert action on South Korea as well as handles overall inter-Korean relations. Neither Korea has officially admitted the existence of the hotline, but it is known that it played a key role in inter-Korean communication, including the arrangement of summit talks. The autobiography of President Kim Dae-jung and the memoir of the former NIS chief Lim Dong-won clearly reveal this point. In fact, President Kim instructed Lim, head of the NIS, to explore establishing a hotline with the North before the Korean summit in 2000. The communication line between the two intelligence agencies was set up after the Pyongyang Summit on June 15, 2000. Although it was not a summit hotline between the two leaders, the intelligence communication line served as a quasi-hotline between them, often contributing to the prevention of escalation of inter-Korean crises.[7][8] As noted before, the first official summit hotline was installed between the Blue House and the KWP’s Headquarters in Pyongyang for the first time on April 20, 2020, a week before the Panmunjom meeting on April 27, 2020. Call quality tests proved to be successful.

A direct telephone line between the United Nations Command (UNC) and the North Korean military at the Panmunjom has been operational since 1998. The direct line was installed in accordance with the ‘Agreement on the Procedure for Hosting General-Level Talks between the UNC and the North Korean Armed Forces’ on June 8, 1998, connecting the UNC Generals office in the southern part of the military demarcation line (MDL) to the North Korean armed forces at the Panmungak in the northern part of MDL of Panmunjom.[9] The line was suspended for five years, however, when the North declared the unilateral invalidation of the armistice agreement by accusing South Korea and the United States of undertaking an aggressive joint military exercise on March 5, 2013. In July 2018, however, the line was restored, owing to an easing of tensions between the two Koreas following the Panmunjom Korean summit in April 2020 as well as improved ties between Pyongyang and Washington, D.C., as evidenced by the Singapore Summit between President Trump and Chairman Kim on June 12th. Recent stalemate notwithstanding, the line is still operational. The UNC conducts daily communication tests with the North Korean military.[10]

Apart from North Korea, South Korea has been operating a hotline with the United States and Japan to prevent military contingencies and facilitate communication on various security issues. At present, direct telephone lines are also operational between South Korea’s 1st Master Control & Remote Center (MCRC) and China’s Northern Theater Command. For example, China notified South Korea of the flight route and purpose when its plane entered the ROK Air Defense Identification Zone (KADIZ) on October 29, 2019.[11] Additionally, South Korea is negotiating the establishment of a military hotline with Russia.

Limitations and Future Tasks

Fifty years have elapsed since the first inter-Korean direct communication line opened in 1971. The inter-Korean hotlines have served as an important confidence-building measure by preventing accidental military clashes and escalation as well as facilitating communication between the two Koreas. The Second Battle of the Yeonpyeong Island in 2002 was a classic example in this regard. On June 29, 2002, a North Korean patrol boat attacked a South Korean Navy high speed boat by surprise, leaving six South Korean sailors dead and 19 injured. North Korea also suffered heavy losses with 13 dead and 25 injured. It was obvious aggressive behavior on the part of North Korea. But the battle did not escalate. According to the memoir of Lim Dong-won, the North instantly sent a message to the South via hotline that said, “This incident was not deliberately planned or intended. We confirm that people of lower ranks on the local level were solely responsible for this unintended clash. We regret this has happened.” It added, “Let’s work together to never let it happen again.” The message indicated that high-level leaders of the North were not involved in the incident and that it was localized. Expressing apology, the North side did not want an escalation of the incident (Lim 2012, 320). Such communication was vital to the prevention of conflict escalation.

The hotlines also played an important role in facilitating inter-Korean relations. For example, improved inter-Korean relations following the first Korean summit in June 2000 were coordinated through the hotline between the NIS and the United Front Department. North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s special envoy Kim Yong-chol’s visit to Seoul in February 2018 and President Moon’s two special envoys dispatch to Pyongyang were all arranged through the NIS-United Front Department hotline. The Ministry of Unification’s official phone line with the North also served as a routine communication channel with the North for exchanging messages, arranging official and unofficial visits, and expressing grievances related to exchanges and cooperation between the two Koreas.

But Pyongyang has repeatedly been cutting off and then resuming hotlines, severely undermining their credibility. Suspension of communication lines has been a typical way of expressing grievances against South Korea. Ever since North Korea opened a direct communication line in 1971, it has shut down communication lines with the South on seven occasions over the duration of 12 years. Let’s examine each of these cases.

The Panmunjom axe incident in 1976: When UN Forces trimmed the poplar tree that limited the view of their third guard post in the Panmunjom Joint Security Area (JSA) on August 18, 1976, North Korean forces attacked them with axes, killing two US officers and injuring nine. Immediately after the incident, the United States and the South Korean troops declared the ‘DEFCON 3’ alert just short of a major military conflict.

Suspension of the working group for the inter-Korean prime ministerial talks in 1980: In January 1980, North Korean Prime Minister Lee Jong-ok proposed a meeting with his South Korean counterpart to improve inter-Korean relations. They held 10 working-level meetings from February to August 1980. But differences between the two, especially regarding the status of US troops in South Korea, could not be narrowed, and the talk was aborted. The North declared the suspension of hotlines unilaterally by attributing the failure of the talk with the South.

South Korea’s co-sponsorship of the North Korea human rights resolution at the 63rd UN General Assembly in 2008: When the South Korean government co-sponsored the UN human rights resolution condemning North Korea, Pyongyang suspended hotlines

Seoul’s May 24th measures in 2010: The Lee Myong-bak government took the May 24 measures that imposed sanctions against North Korea in retaliation to the sinking of the ROK Cheonan corvette by North Korea on March 26, 2010. They included banning North Korean ships from sailing in South Korean waters, prohibiting visits by South Koreans to North Korea, halting all inter-Korean trade and investments in the North, and suspending all aid projects. In response, the North, which denied any wrongdoings, cut off all communication lines.

UN Security Council sanctions in 2013 and joint ROK-US military exercises: The UN Security Council adopted a new resolution on sanctions against North Korea’s third nuclear test on February 12, 2013, and South Korea abided by it. The North suspended hotlines in protest.

The Kaesong Industrial Complex suspension measures in 2016: When North Korea executed its fourth nuclear test on January 6, 2016, the South Korean government closed the Kaesong Industrial Complex, withdrew its workers and companies, and suspended power and water supply on February 10, 2016. The North reciprocated by suspending all communication lines.

Propaganda Leaflet Sending: On June 9, 2020, Pyongyang cut off all inter- Korean communication lines after Kim Yo Jung, sister of the North Korean leader, issued a statement on June 4 that described inter-Korean relations as hostile. North Korean defectors’ distribution of propaganda leaflets to the North, Seoul’s failure to implement what has been agreed in Panmunjom and Pyongyang, and worsened DPRK-US relations contributed to the decision.[12]

Inter-Korean hotlines have been subject to ups and downs, depending on the nature of relations between the two Koreas as well as that between North Korea and the United States. At present, only two communication lines are operational, one between the UNC and the North Korean military in Panmunjom and the other for air traffic control. This means that there have been no communication lines between the South and the North since June 9, 2020. Seoul is eager to reactivate communication lines, but Pyongyang has not responded. Some positive signals came from the North in September 2020 in light of an exchange of personal letters between the two leaders, but there have been no further developments.

The episode of a shooting death of a South Korean official by the North Korean navy on September 22, 2020. shows the lack of communication channels can complicate inter-Korean relations. A South Korean government official disappeared in the early morning of September 21 from a maritime guidance ship that belonged to the ROK Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fishery. According to the Ministry of National Defense, the official who crossed the Northern Limit Line, and who was believed to defect to the North, identified himself as a South Korean governmental official, but North Korean navy officers shot him to death and set him on fire for the reason of Covid-19 quarantine. If military communication lines in the West Sea were operational, the tragedy could have been prevented. Likewise, cutting off communication lines between the two Koreas has not only heightened the potential for accidental clashes and conflict escalation, but also deprived them of a means to enhance mutual confidence-building.

Another critical limitation is a rather underdeveloped telecommunication infrastructure in North Korea that made effective communication difficult. Most of the inter-Korean hotlines were composed of copper cables, so the quality of communication was poor and intermittent. Video conferencing was virtually impossible. Since 2007, however, optic fiber cables were installed to support the video reunion of separated families and the firms at the Kaesong Industrial Complex. The inter-Korean Joint Liaison Office (which is now demolished by the North) and military communication lines were also connected through optic fiber cables. But in general, overall communication networks in the North were underperforming. Realizing this problem, the South and the North “shared the awareness of the need to improve the existing communications networks between the inter-Korean authorities and to cooperate in the future” at the inter- Korean communication working group held at the North-South Joint Liaison Office on November 23, 2018.[13] When and if inter-Korean relations normalize, one of the first tasks will be the improvement of communication infrastructure in the North.

In conclusion, we argue that the hotline is one of the most important components of confidence-building measures. It has played a key role in not only preventing accidental military clashes and unintended conflict escalation, but it has also facilitated exchange and cooperation between the two Koreas. The inter-Korean hotline has been subject to excessive politicization by North Korea, however, making it alternate between suspension and resumption. Such instability in communication can make overall security on the Korean peninsula more precarious and uncertain. Judged on the current nuclear stalemate, it will not be easy to restore mutual trust and to reactivate hotlines between Seoul and Pyongyang. The technical constraints of the outdated communication infrastructure pose another challenge.

We can conclude two policy implications. One, the issue of a hotline not only between the North and the South, but also between the DPRK and the United States, should be incorporated as an integral part of nuclear negotiations with North Korea. At the same time, Seoul must make every effort to restore broken communication lines with Pyongyang. The other is to modernize and upgrade North Korea’s communication infrastructure. In this regard, the introduction of CataLink-style modernized hotlines into North and South Korea should be seriously considered and debated.

III. ENDNOTES

[1] Article 7 of the Inter-Korean Basic Agreement stipulates that “the South and the North will stop confrontation and competition on international stage, cooperate with each other, and make joint efforts for the dignity and interests of the people.” Article 13 also states that “the South and the North will establish and operate direct telephone lines between the military authorities of the two sides to prevent occurrence and expansion of unintended military clashes.”

[2] They include 5 lines for the inter-Korean Joint Liaison Office, 21 lines for Seoul-Pyongyang official talks support, 2 lines for air traffic control cooperation between Incheon and Pyongyang, 2 lines for maritime authorities in Seoul and Pyongyang, and 3 lines for the inter-Korean joint committee of the Kaesong Industrial Complex.

[3] Jin-ho Kim, “’This is Pyongyang, it rains,’ History of North-South Peace Hotline,” Kyunghyang Shinmun, April 20, 2018 (in Korean).

[4] ‘Military Assurance Agreement on the East Sea District and West Sea District Inter-Korea Joint Administration Area Configuration, South-North Railroad and Road Construction,’ September 17, 2002.

[5] Ministry of National Defense, report to the National Assembly, July 16, 2020. (in Korean)

[6] Kyunghyang Shinmun, op. cit., April 20, 2018.

[7] Kim, Dae-jung. 2010. Autobiography 2. Seoul: Samin.

[8] Lim, Dong-won. 2012. Peacemaker: Twenty Years of Inter- Korean Relations and the North Korean Nuclear Issue. Stanford: Asia-Pacific Research Center.

[9] Kui-keun Kim, “North Korea’s claim of invalidation of the armistice agreement is contradictory,” Yonhap News, March 7, 2013. (in Korean) https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20130307163200043.

[10] Jeong-wook Kim, “Despite cut-off of inter-Korean military communication line, the UNC-North Korea Military direct phone line is still operational,” The Seoul Economic Daily, June 19, 2020. (in Korean)

[11] Kui-keun Kim, “Chinese military plane entered the KADIZ near Yieodo after notifying through a hotline,”” Yonhap News, October 29, 2019. (in Korean) https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20191029063751504.

[12] Materials distributed to the Ministry of Unification press corps, “Past cases of North Korea’s suspension of direct telephone lines,” June 9, 2020.

[13] Tae-woo Park, “North-South agreed to cooperate with other in replacing existing communication lines with optic fiber cable,” Hankyoreh, November 23, 2018. (in Korean).

IV. NAUTILUS INSTITUTE INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

Nautilus Institute invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.