Changing Dynamics of U.S. Extended Nuclear Deterrence on the Korean Peninsula

Special Report, November 10, 2010

Cheon Seongwhun

——————–

CONTENTS

II. Article by Cheon Seongwhun

IV. Nautilus invites your responses

I. Introduction

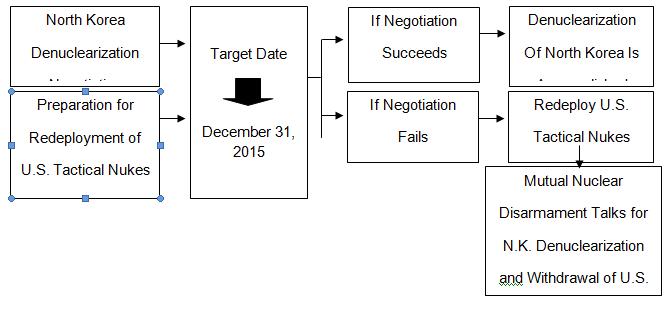

Cheon Seongwhun writes, “…some safeguard measures are necessary to supplement the diminishing American nuclear umbrella on the Korean peninsula. Noting that the uniqueness of the threat to South Korea makes it a suitable place to actively apply the new concept of the regionally tailored deterrence architecture, this paper proposes to implement a dual-track approach of negotiation of the North Korean nuclear crisis in tandem with preparation for the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in the ROK. If the negotiation track fails to resolve the crisis, then United States should redeploy a few dozen tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea and offer to hold mutual nuclear disarmament talks with North Korea to barter the withdrawal of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons for the elimination of North Korean nuclear weapons.”

“The Russian Federation will not use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon States Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, except in the case of an invasion or any other attack on the Russian Federation, its territory, its armed forces or other troops, its allies or on a State towards which it has a security commitment, carried out or sustained by such a non-nuclear-weapon State in association or alliance with a nuclear-weapon State.”In particular, France noted that it had sought as much as possible to harmonize the content of its negative assurances with those of the other nuclear weapon states and said that it was pleased that this effort has been successful. China issued a separate unconditional negative security assurance as following: “China undertakes not to be the first to use nuclear weapons at any time or under any circumstances. China undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear-weapon-free zones at any time or under any circumstances.”[5]President Obama’s Nuclear Posture Review and Negative Security AssuranceThe United States released a new Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) on April 6, 2010. [6] The Obama Administration’s NPR delivers the following five points as the core of the new nuclear policy:

- Preventing nuclear proliferation and nuclear terrorism;

- Reducing the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in U.S. national security strategy;

- Maintaining strategic deterrence and stability at reduced nuclear force levels;

- Strengthening regional deterrence and reassuring U.S. allies and partners;

- Sustaining a safe, secure, and effective nuclear arsenal.

The status of U.S. extended nuclear deterrence is directly relevant to the second point. The NPR establishes that the “fundamental role” of its nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attacks against the United States and its allies. The NPR amends the pre-existing conditional negative security assurance to clarify a new, strengthened NSA strategy: “The United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear nonproliferation obligations.”A major feature of this new NSA is that it has eliminated the exception clause of the pre-existing conditional NSA. As long as non-nuclear weapon states join the NPT and carry out their obligations, even if they attack the United States or its allies with chemical or biological weapons, to say nothing of conventional weapons, the United States clearly declares that it will not retaliate with nuclear weapons. [7] In other words, as opposed to the past when the option was preserved for nuclear retaliation against North Korea in the event of an invasion of South Korea, if North Korea joins the NPT and abandons its nuclear weapons, the United States promises not to use nuclear weapons to repel North Korean aggression.The Obama Administration does not disguise the fact that the new policy of “no nuclear retaliation” against non-nuclear NPT member states is targeted at North Korea as an inducement for denuclearization. At a press conference, Principal Deputy Under-Secretary of Defense James Miller explained that “part of the rationale for the negative security assurance and its change was, in fact, to encourage North Korea to go the opposite direction and to desire to be one of those states that are compliant with their nuclear nonproliferation obligations.” [8] Secretary of Defense Robert Gates also mentioned that “so if there is a message for Iran and North Korea here, it is that if you’re going to play by the rules, if you’re going to join the international community, then we will undertake certain obligations to you, and that’s covered in the NPR.” [9]Regarding the new NPR, critical views have been expressed both within and without the United States. For example, Senators John McCain and Jon Kyl contended that the Obama Administration’s polices including the new NPR have failed to directly confront the two leading proliferators and supporters of terrorism, Iran and North Korea, and that “this failure has sent exactly the wrong message to other world-be proliferators and supporters of terrorism.” [10] Other critics also suggest that the conditions under which nuclear weapons cannot be used are too specific and thus damage the element of “strategic ambiguity” which deters America’s enemies from using armed forces; [11] it is ridiculous to proscribe America’s use of nuclear weapons even if the U.S. mainland suffers massive casualties from a NPT-member non-nuclear weapon state’s chemical or biological attack; [12] limits on the use of nuclear weapons will make a war more likely; [13] some of the U.S. allies may doubt whether the nuclear umbrella still covers them and may start planning an alternative, [14] and one cannot expect that North Korea and Iran will stop their nuclear programs just because the United States promises not to make any nuclear threats, in fact they will be more inclined to move toward obtaining nuclear weapons in the absence of such a threat.[15]Implications to the ROK SecurityNothing will change the current policy of U.S. extended nuclear deterrence on the Korean peninsula as long as North Korea holds on to nuclear weapons. Ironically, however, South Korean security could be weakened after North Korea’s denuclearization because of the huge loophole created by the new NSA. Denuclearization does not guarantee a peaceful North Korea; that could be made possible only by revolutionary changes in the DPRK leadership. Once North Korea gives up nuclear weapons, the U.S. nuclear umbrella will disappear from the Korean peninsula. Then, South Korea must confront the still formidable North Korean asymmetric military capabilities such as chemical and biological weapons, forward-deployed artillery, missiles, submarines and special forces.A new strategic assessment by the United States Forces Korea (USFK) indicates that North Korea has spent its dwindling coffers to build a surprise attack capability specifically designed for affecting the economic and political stability of South Korea “with little or no warning”.[16] Danger of overlooking North Korea’s asymmetrical capabilities has been warned by several experts both in South Korea and the United States. [17] One American expert pointed out that “the North Korean military threat of 2010 is not the same as that of 1990 against which South Korea has been so well prepared to defend.” [18] According to him, North Korea’s military threat has not subsided in spite of overwhelming resource constraints, and, by focusing limited resources on asymmetric forces, “North Korea has maintained its capability to threaten the South, and has also continued to maintain its belligerent and uncooperative foreign policy.” [19] In this context, he proposed delaying the timing of the wartime operational control (OPCON) transfer from the U.S. to the ROK. [20] At the “2+2 meeting” of foreign and defense ministers of the two countries in July 2010, the ROK and the United States agreed to delay the transfer of wartime OPCON to South Korea until December 2015. [21]The Cheonan sinking that occurred in March 2010 is a vivid manifestation of the harsh security realities on the Korean peninsula. At 9:22 p.m. Friday evening of March 26, 2010, the South Korean navy corvette Cheonan sank just South of the Northern Limit Line (NLL) near Baekryongdo Island in the West Sea. A sudden underwater explosion ripped the battle ship in two parts, killing 46 out of 108 sailors on board. The Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group (JIG) was formed with 25 experts from 10 South Korean institutions and 24 foreign experts from the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Sweden, and Canada. On May 20, the JIG reported the result of its two month-long investigation, and concluded that:“Based on all such relevant facts and classified analysis, we have reached the clear conclusion that ROKS “Cheonan” was sunk as the result of an external underwater explosion caused by a torpedo made in North Korea. The evidence points overwhelmingly to the conclusion that the torpedo was fired by a North Korean submarine. There is no other plausible explanation.”[22]According to James Clapper, Jr., the Director of National Intelligence, the most important lesson from the Cheonan incident is “to realize that we may be entering a dangerous new period when North Korea will once again attempt to advance its internal and external political goals through direct attacks on our allies in the Republic of Korea. Coupled with this is a renewed realization that North Korea’s military forces still pose a threat that cannot be taken lightly.” [23] Although the U.S. security commitment will remain and may be reinforced by other, non-nuclear elements as the new NPR indicates, it will not be easy to reassure either South or North Korea that extended deterrence without the nuclear component is as solid as before.In the past, with the pre-existing conditional NSA, the United States provided a qualified nuclear security guarantee to North Korea and an all-weather security assurance to South Korea. By adopting the new NPR and the new NSA omitting the exception clause, the United States is willing to provide an unqualified nuclear security guarantee to denuclearized North Korea and a managed security assurance to South Korea. In comparison, if North Korea forgoes its nuclear weapons, the U.S. nuclear umbrella will be gone, and the overall U.S. deterrence system will be punctured by a huge, nuclear hole. The U.S. blank check for South Korean security will be replaced with a fixed check missing the value of nuclear retaliation.History of the U.S. Security Guarantees to North KoreaThe North Korean response to the Obama Administration’s new nuclear strategy was negative. On April 9, a Foreign Ministry spokesperson pointed out that the new NPR leaves North Korea and Iran as targets for nuclear retaliation and complained that it is no different from the hostile policy of the early Bush Administration, which set North Korea as a target of nuclear preemptive strike and habitually made nuclear threats.[24] At the same time, the spokesperson criticized the new NPR for completely overturning the pledge made in the September 19th Joint Declaration not to use nuclear weapons and for throwing cold water on the prospect of re-opening the Six-Party Talks. Finally, the spokesman declared that North Korea will continue to increase and modernize its nuclear stockpile as much as it deems necessary. All in all, it is quite unlikely that the Obama Administration’s new NSA will entice North Korea to give up nuclear weapons.At this juncture, it is important to remember that since the outbreak of the North Korean nuclear crisis, there have been constant worries that the U.S. nuclear umbrella for South Korea has shrunk. North Korea has persistently used the “American threat” argument to counter U.S. attempts to stop its nuclear weapons development program. That is, North Korea has argued that it has to develop nuclear weapons for defensive purposes against the conventional and nuclear threats from the United States. Surprisingly, this argument is gaining acceptance from the United States as the nuclear crisis has developed during the past two decades.The U.S.-DPRK High-Level Talks in the Early 1990sIn the early 1990s, North Korea successfully used the nuclear issue as a lure to draw Americans to the first bilateral high-level talks after the end of the Korean War. North Korea’s announcement that it would withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) brought about fundamental changes in America’s long-held position not to have direct high-level contact with North Korea. Anxious for extending the effectuation of the NPT permanently in the upcoming Review and Extension Conference in 1995, the Clinton Administration discarded a fundamental principle of U.S. diplomacy vis-à-vis North Korea. As a result, there had been a series of high-level talks from the summer of 1993 to the fall of 1994. Joint statements were issued at the end of the talks where the United States formally pledged not to use or threaten to use armed force, including nuclear weapons, against North Korea.At the conclusion of the first U.S.-DPRK high-level talks on June 11, 1993, the two countries agreed to the following principles:

- assurances against the threat and use of force, including nuclear weapons;

- peace and security in a nuclear-free Korean peninsula, including impartial application of full-scope safeguards, mutual respect for each other’s sovereignty, and non-interference in each other’s internal affairs;

- support for the peaceful reunification of Korea. [25]

At the end of the second high-level talks on July 19, 1993, both sides reaffirmed the principles of the June 11 Joint Statement. The United States specifically emphasized to the DPRK “its commitment to the principles on assurances against the threat and use of force, including nuclear weapons.” [26] At the end of the first round of the third high-level talks on August 12, 1994, the United States also promised that “to help achieve peace and security on a nuclear-free Korean peninsula, the U.S. is prepared to provide the DPRK with assurances against the threat or use of nuclear weapons by the United States.”[27]North Korea perceived that the pre-existing, conditional NSA was a nuclear threat and strongly demanded that the United States eliminate it. To North Koreans, withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons in South Korea was not enough to meet this demand. According to the various statements made by North Korean officials, the ROK/U.S. joint military exercises, U.S. nuclear weapons which North Koreans believed were stationed in Okinawa and other U.S. bases in Asia, and U.S. strategic nuclear forces constitute American nuclear threats. During the U.S.-DPRK high-level talks, North Korea reportedly demanded an official document to guarantee the elimination of the U.S. nuclear threat.In addition, North Korean officials have argued that nuclear weapon states should provide non-nuclear weapon states with an unconditional and legally binding promise not to use nuclear weapons. For example, in 1994, at the third Preparatory Committee Meeting for the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference, North Korea criticized that the NPT reflected the situations of 25 years ago and was discriminatory and unbalanced. It argued that the treaty should be revised in accordance to the changed circumstances and proposed that the following measures be incorporated into a new NPT: (1) to prohibit the deployment of nuclear weapons on the other countries’ territories, the high seas and the outer space, (2) to guarantee the creation of nuclear weapon free zones, (3) to provide an unconditional and legally binding security assurance against the threat or use of nuclear weapons, (4) to ban nuclear testing comprehensively, and (5) to accomplish a general and complete nuclear disarmament.[28]In his address at the 49th session of the UN General Assembly on October 5, 1994, North Korean Vice Foreign Minister Choe Suhon also emphasized that in order to be an impartial treaty, the NPT should contain the following measures: (1) an unconditional assurance against the threat or use of nuclear weapons, (2) a promise of no first use of nuclear weapons, (3) a total ban of the use of nuclear weapons, (4) a stop of the production of nuclear weapons, and (5) a presentation of time table to eliminate nuclear weapons completely.[29]The Agreed Framework in 1994The Agreed Framework was signed in Geneva on October 21, 1994 at the last round of the third high-level talks between the United States and North Korea. As a result of the 17 month-long, intensive negotiations, the document covered across-the-board issues in bilateral relations and consisted of four major parts:

- cooperating to replace the DPRK’s graphite-moderated reactors and related facilities with light-water reactor (LWR) power plants (Article I);

- moving toward full normalization of political and economic relations (Article II);

- working together for peace and security on a nuclear-free Korean peninsula (Article III);

- working together to strengthen the international nuclear non-proliferation regime (Article IV). [30]

Article III.1 of the Agreed Framework says that “the U.S. will provide formal assurances to the DPRK, against the threat or use of nuclear weapons by the U.S.”[31] The Clinton Administration never officially clarified the relationship between its pre-existing conditional NSA and the non-use commitment given to North Korea during the bilateral high-level talks. When the Agreed Framework was signed, for example, conflicting views on the issue of negative security assurance emerged within the United States. On the one hand, the fact sheet released immediately after the Agreed Framework attached a condition that the non-use guarantee would be provided under certain defined circumstances [emphasis added].[32] Specifically, a State Department official told the author that the security guarantee that would be given to North Korea was similar to that provided to the Ukraine. In the Trilateral Statement signed in January 1994, the United States and Russia promised to provide a conditional NSA that retained the option of nuclear retaliation. [33]On the other hand, there existed a compelling view that the U.S. non-use guarantee to the DPRK was without exception and thus, contradictory to its traditional negative security assurance policy. In other words, the agreement made a hole in the U.S. nuclear umbrella over South Korea. The argument was that by faithfully implementing the Agreed Framework, the United States could not use nuclear weapons even in the case of a North Korean invasion of South Korea. Therefore, it would be harmful to the U.S. forces in Korea not to mention South Korean security and the ROK-U.S. alliance. There are three examples where such a concern was expressed.First, according to a draft of the U.S. Congressional Resolution submitted in January 1995, the Clinton Administration’s non-use commitment to the DPRK was regarded as an unconditional guarantee. The draft resolution stipulated that “under the terms of the Framework Agreement the United States promises not to threaten or use nuclear weapons against the DPRK. This removes the best security guarantee for American troops on the Korean peninsula, the possibility of a nuclear response to a DPRK invasion.” [34] The Resolution asked President Clinton to retain “the option of a nuclear response if the DPRK attacks U.S. troops in the ROK.”Second, the American Security Council Foundation also concluded that a guarantee not to use nuclear weapons against North Korea in the event of a war was one of many concessions made by the United States in the Agreed Framework. Arguing that the possibility of a nuclear response to a North Korean blitz had been the best guarantee of the security of U.S. troops in South Korea, the Foundation recommended that in order to improve the Agreed Framework, “the United States should not renounce the use of nuclear weapons against the DPRK in a time of conflict.” [35]Finally, the author discussed this issue with Lieutenant General John Cushman (retired), who served as a Field Commander of the USFK from 1976 to 1978. He was told about the developments of the North Korean nuclear problem and American security guarantees to North Korea. General Cushman asked the author whether the United States committed not to use nuclear weapons against North Korea. When the author said “yes,” he stated that “it is contradictory to the U.S. nuclear umbrella to Seoul.” [36] It is believed that General Cushman’s remark echoed many American experts and officials who had first-hand knowledge on the Korean peninsula security issues.It seems that the United States and North Korea never had in-depth discussions on this issue during the bilateral high-level talks. According to the Nuclear Posture Review released by the Clinton Administration in September 1994, an unconditional NSA is in violation of the U.S. nuclear strategy. [37] This means that although the Clinton Administration did omit the exception clause in the agreement with North Korea, in practice, it still held on to the pre-existing, conditional negative security assurance. Considering that North Korea continued to demand the removal of the U.S. nuclear threat even after the Agreed Framework was signed, the North Korean leadership probably believed that the Clinton Administration’s NSA was not comprehensive enough to invalidate the exception clause.Regardless of the exact meaning of the NSA given to North Korea, the fact is that a series of American security guarantees to the DPRK during the eight years of the Clinton Presidency diminished the effect of the U.S. nuclear umbrella over South Korea. The Joint Statement in June 1993 and the Agreed Framework in October 1994 set the course for the U.S.-DPRK interactions that followed. For example, on October 12, 2000, a joint communiqué was agreed on the occasion that the North Korea’s Special Envoy, Vice Marshal Jo Myong-rok visited the United States and met President Clinton. In return, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright visited Pyongyang and met Kim Jong-Il. The communiqué stipulated various measures to improve the U.S.-DPRK relations, including that:“Building on the principles laid out in the June 11, 1993 U.S.-DPRK Joint Statement and reaffirmed in the October 21, 1994 Agreed Framework, the two sides agreed to work to remove mistrust, build mutual confidence, and maintain an atmosphere in which they can deal constructively with issues of central concern. In this regard, the two sides reaffirmed that their relations should be based on the principles of respect for each other’s sovereignty and non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, and noted the value of regular diplomatic contacts, bilaterally and in broader fora.” [38]A critical component of the two documents is that the United States provided security guarantees to North Korea for the first time since the end of the Korea War. This promise has been a foundation to build and sustain the follow-on bilateral relationship. More importantly, since the security guarantee was an incentive to entice North Korea to forgo its nuclear weapons development program, it had the unintended consequence of supporting North Koreans’ longstanding argument that it was the American security threat, including nuclear intimidation, which actually prompted them to develop nuclear weapons.The September 19th Joint Declaration in 2005Despite political differences from the Clinton Administration, the U.S. security guarantee to North Korea continued during the Bush Administration. It was a surprise to many in South Korea and Japan that President Bush made a security commitment similar to that of his predecessor to North Korea. Under the motto of ABC (Anything But Clinton), Bush Administration officials heavily criticized and vowed to overhaul the Clinton Administration’s North Korea policy. In his confirmation hearing, for example, Secretary of State Colin Powell referred to Kim Jong-il as “the dictator” and said that the United States and its allies in the Pacific would remain vigilant as long as North Korea’s military threat continued. He further stated that “in conjunction with Secretary-designate Rumsfeld, we will review thoroughly our relationship with the North Koreans, measuring our response by the only criterion that is meaningful—continued peace and prosperity in the South and in the region.”[39]He also pointed out that verification and monitoring regimes were missing from the Clinton Administration’s negotiations with North Korea. [40] President Bush expressed “some skepticism about the leader of North Korea” and worried that part of the problem in dealing with North Korea was the lack of transparency. [41] The three leading House members urged President Bush not to prejudice his ability to refine U.S. policy toward North Korea by committing himself to the Agreed Framework.[42]The current nuclear crisis erupted in October 2002 when the Bush Administration correctly revealed the DPRK’s secret highly-enriched uranium (HEU) program which was developed in collaboration with Pakistan and had long been ignored by the Clinton Administration. Contrary to its initial principled position on North Korea and its nuclear weapons program, President Bush changed his policy and offered many incentives to North Korea. The security commitment provided by the Bush Administration was stipulated in the September 19th Joint Declaration which was agreed upon at the Fourth Round of the Six-Party Talks in 2005. Article 1 of the declaration says that “the United States affirmed that it has no nuclear weapons on the Korean Peninsula and has no intention to attack or invade the DPRK with nuclear or conventional weapons.”[43] In a bid to make progress in the denuclearization of North Korea, the Bush Administration also provided an important carrot to North Korea, rescinding the designation of the DPRK as a state sponsor of terrorism, to no avail. On October 11, 2008, the State Department removed North Korea from the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism, meeting a major demand of the North. The DPRK, however, made no reciprocal action to dismantle its nuclear weapons program or verify its denuclearization.In short, in the early 1990s, North Korea used the desertion of its nuclear weapons development programs as bait to extract repeated promises from the United States not to use or threaten to use military force, including nuclear weapons. Almost 20 years later, the DPRK is using the abandonment of nuclear weapons as a pretext for demanding the United States remove military threats and insisting on a peace treaty which aims to nullify the Armistice Agreement, the foundation of the ROK-U.S. joint deterrence. This is the reality of the North Korean nuclear crisis today.ROK Security Interests Undermined by U.S. Political InterestsAn important lesson from the two decade-long process of North Korea nuclear negotiation is the fact that American politicians’ political interests and their attempts to create legacies have undermined South Korea’s security interests. In particular, some policies of the Clinton and Bush Administrations to resolve North Korea’s nuclear crisis weakened the security of the ROK and can only be explained by the two Administrations’ drive to create a positive political legacy.Bill Clinton PresidencyPresident Clinton knew that the DPRK had developed a HEU program with the help of Pakistan and violated the Agreed Framework. The report to the Speaker of House of Representatives in November 1999 stated that:“North Korea’s WMD programs pose a major threat to the United States and its allies. This threat has advanced considerably over the past five years, particularly with the enhancement of North Korea’s missile capabilities. There is significant evidence that undeclared nuclear weapons development activity continues, including efforts to acquire uranium enrichment technologies and recent nuclear-related high explosive tests. This means that the United States cannot discount the possibility that North Korea could produce additional nuclear weapons outside of the constraints imposed by the 1994 Agreed Framework.” [44]President Clinton did not disclose this fact, however, for fear that his diplomatic legacy centered on the Agreed Framework might be damaged.[45] Instead, he accelerated normalization talks with North Korea, exchanged high-ranking officials, and issued a joint communiqué as if the North had loyally adhered to its promise to abandon nuclear weapons programs. As discussed earlier, the joint communiqué affirmed that based on the principles laid out in the 1993 Joint Statement and reaffirmed in the 1994 Agreed Framework, the two sides would improve their bilateral relationship.In February 2000, President Clinton disregarded the Congressional request to certify that North Korea was not seeking to develop nuclear weapons. In response to President Clinton’s request for funding the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO), the Congress asked the President to certify that:

- North Korea is complying with all provisions of the Agreed Framework and progress is being made on the implementation of the Joint Denuclearization Agreement between North and South Korea;

- North Korea is cooperating fully in the canning and safe storage of all spent fuel from its 5MWe reactor;

- North Korea has not significantly diverted assistance provided by the United States for purposes for which it was not intended; and

- The United States is fully engaged in efforts to impede North Korea’s development and export of ballistic missiles.[46]

On February 24, 2000, President Clinton spent 1.5 million dollars to fund KEDO by waiving the requirements to certify that:

- North Korea has not diverted assistance provided by the United States for purposes for which it was not intended; and

- North Korea is not seeking to develop or acquire the capability to enrich uranium, or any additional capability to reprocess spent nuclear fuel. [47]

The much praised Perry Report which was produced in October 1999 by William Perry, then U.S. North Korea Policy Coordinator and Special Advisor to the President and the Secretary of State, set out last-ditch diplomatic efforts toward North Korea. However, the report articulated as its basic premise that “the policy review team has serious concerns about possible continuing nuclear weapons-related work in the DPRK.” [48]George W. Bush PresidencyOn October 11, 2008, the U.S. State Department removed North Korea from a list of State Sponsors of Terrorism, meeting a major demand of Pyongyang in anticipation of North Korea’s reciprocal good behavior in verifying its denuclearization. Contrary to expectations, this decision did not give the Kim Jong-il regime any substantial benefits. North Korean society had to reform and open for the delisting to bear economic fruits. Additionally, about 20 other sanctions remained unchanged. The U.S. decision, however, helped Kim Jong-il reinforce his political legitimacy and authority that might have been otherwise weakened by his illness. Believing that their Dear Leader had personally beaten President Bush without forgoing their nuclear weapons, North Korean elites could have launched a domestic propaganda campaign supporting Kim Jong-il. Internationally, the Bush Administration’s decision might have encouraged reckless behavior from other would-be proliferators.A major motivation to rescind the designation of the DPRK as a State Sponsor of Terrorism was the Bush Administration’s aspiration for creating a positive legacy after its remaining tenure. Bogged down in the Iraq War, isolated on the world stage, and with no concrete achievements domestically, President Bush regarded the North Korean nuclear crisis as an opportunity to produce a political legacy in his later days at the White House. In the course of what John Bolton called “legacy frenzy,”[49] the Bush Administration surrendered key principles, such as not having direct bilateral contacts with North Korea and insisting on complete, verifiable, and irreversible dismantlement (CVID), and devoted itself just to producing an agreement. The outcome was disappointing: much less thorough disablement than originally promised in February 2007, a declaration missing major parts of the DPRK nuclear programs such as the uranium enrichment and proliferation activities, no assurance of when and how nuclear weapons will be dismantled, and inadequate verification with many loopholes.The current nuclear crisis occurred in October 2002 when the Bush Administration disclosed the DPRK’s HEU program which had long been hidden by the Clinton Administration’s legacy frenzy. Few would have believed that President Bush would have followed the exactly same path as President Clinton. Critical observation of American politicians’ legacy drive is not an isolated view in South Korea. In a Foreign Affairs article, Yoichi Funabashi, the editor-in-chief of the Asahi Shimbun, cited veteran Japanese diplomats’ views that Secretary Rice’s drive to build her legacy by scoring a diplomatic success with North Korea in the later days of the Bush Administration was a disconcerting replay of Secretary Madeleine Albright’s final days in the Clinton Administration, when she feverishly tried to arrange a visit to Pyongyang for President Clinton.[50]Safeguards to the Diminishing U.S. Nuclear UmbrellaIt is difficult to argue that the Korean peninsula has been more stable and secure since the end of the Cold War. While the world has gone through much change and transformation under the motto of globalization, in the security field, new threats have emerged as old ones remained. Despite wide spread of euphoria after the end of the Cold War, many parts of the world have come face to face with terrorism as a new threat, especially after the tragedy of 9/11.On the Korean peninsula, the old threat of potential interstate confrontation has remained for six decades. The fundamental reason for this threat is that North Korea is governed by an authoritarian dictatorship that shows no sign of opening and reforming its system. While South Korea has committed itself to promoting inter-Korean relations based on mutual reconciliation, exchanges, and cooperation, North Korea still maintains the policy of national revolution and unification of the Korean Peninsula by force.Under these circumstances, the Obama Administration made a historic decision to reduce the role of nuclear weapons with an ambitious goal of the world without nuclear weapons. This decision will inevitably have the effect of shrinking the nuclear umbrella the United States provides to its allies. President Obama’s nuclear strategy faces various challenges both within and without the United States, and it’s not clear whether political momentum of his new nuclear policy will be sustained in the future.At the same time, the U.S. Administration has proposed a concept of “regionally tailored deterrence architecture” (RTDA) as a new framework to build regional deterrence systems. Recognizing that “Europe is not Asia is not the Middle East,” [51] the new concept attempts to distinguish diverse regions, identify specific threats and security challenges pertinent to each region, and to provide allies in the region with suitable deterrence means and tools to meet those threats and challenges. That is, the essence of the RTDA is believed to be tailoring the U.S. extended deterrence capabilities, including nuclear assets, depending on the regions where security threats and defense needs are different.Regionally Tailored Deterrence ArchitectureThe Obama Administration disclosed the concept of “regionally tailored deterrence architecture” in the three major policy review documents. First, the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) affirms that “credibly underwriting U.S. defense commitments will demand tailored approaches to deterrence. Such tailoring requires an in-depth understanding of the capabilities, values, intent, and decision making of potential adversaries, whether they are individuals, networks, or states.”[52] It further states that:“To reinforce U.S. commitments to our allies and partners, we will consult closely with them on new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent. These regional architectures and new capabilities, as detailed in the Ballistic Missile Defense Review and the forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review, make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.”[53]Second, the Ballistic Missile Defense Review (BDMR) argues that “regional approaches must be tailored to the unique deterrence and defense requirements of each region, which vary considerably in their geography, in the history and character of the threat, and in the military-to-military relationships on which to build cooperative missile defenses.”[54] The BMDR also states that the development of these regional architectures will be guided by such principles as (1) working with allies and partners to strengthen regional deterrence architectures that must be built on the foundation of strong cooperative relationships and appropriate burden sharing, and (2) to pursuing a phased, adaptive approach within each region that is tailored to the threats and circumstances unique to that region. [55]Third, the Nuclear Posture Review notes that strengthening regional deterrence and reassuring U.S. allies and partners is one of the five key objectives of the Obama Administration’s nuclear weapons policies and posture. While noting that the U.S. allies in different regions face different security threats, the NPR acknowledges that “there are separate choices to be made in partnership with allies in Europe and Asia about what posture best serves our shared interests in deterrence and assurance and in moving toward a world of reduced nuclear dangers.” [56]In Europe, a small number of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons still remain as an additional safeguard to European security. This is combined with NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements under which non-nuclear member nations participate in nuclear planning and possess specially configured aircraft capable of delivering nuclear weapons. In Asia, however, there is neither the presence of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons nor NATO-type nuclear sharing arrangements. When the Cold War was over, all forward-deployed nuclear weapons were withdrawn from the Asia-Pacific region and the United States removed nuclear weapons from naval surface vessels and general purpose submarines.The Dual-Track Approach as a Safeguard to the ROK SecurityThe Korean peninsula is the right place for the new regionally tailored deterrence architecture concept to be applied because the security threats are indeed unique compared to other parts of the world. The military threat posed by North Korea is unprecedented at least in five aspects. First, in spite of the dire economic difficulties, North Korea has heavily invested its limited resources on asymmetric military capabilities. It tested nuclear devices in 2006 and 2009, and possesses chemical and biological weapons programs. A recent report by the U.S. State Department hints that North Korea has continued to develop biological weapons and may use them. [57] Second, the future of North Korea is of great concern given the ongoing power succession process from Kim Jong-Il to his third son. The Cheonan incident may be a harbinger of renewed North Korean provocations in the tricky period of power transition. On August 12, 2010, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates voiced suspicion that until the succession process is settled, the attack on the Cheonan may not be the only provocation from North Korea. [58]Third, North Korea has elevated the level of threat to South Korea. Previously, the North Korean threat was largely based on conventional weapons. For example, in 1994, the DPRK threatened to “turn Seoul into a sea of fire.” [59] After proclaiming that it possessed nuclear weapons, North Korea began to threaten to “incinerate the entire South Korea.” [60] Fourth, North Korea is suspected to be the number one country proliferator of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) related technologies and materials. For example, it helped to construct an advanced version of the 5MWe reactor in Syria despite repeated requests of the international community not to proliferate its nuclear technologies. Finally, the U.S. nuclear umbrella to South Korea has diminished continuously since the beginning of the North Korean nuclear crisis in the early 1990s.Considering the uniqueness of security threat faced by South Korea, this paper proposes building a Korean Peninsula Tailored Deterrence Architecture including the presence of American tactical nuclear weapons in South Korean territory. Being faithful to the core concept of the regionally tailored deterrence architecture, there is no other place in the world except South Korea that deserves first-hand access to the U.S. extended nuclear deterrence. The Korean peninsula needs a new deterrence architecture that can match the unprecedented threat from North Korea. In this respect, it is rather ironic that U.S. tactical nuclear weapons are deployed in Europe where there does not exist any imminent nuclear threat to U.S. allies in the region. As Americans argue, Russia is no longer an enemy to the United States and the Western European countries. Iran’s nuclear program is troublesome but still is far from being an urgent danger that warrants the threat of nuclear retaliation from Western Europe.Pessimistic views prevail that it is unlikely that the North Korean nuclear crisis will be resolved through negotiations anytime soon. Frustrations have been mounted especially given that the Six-Party Talks, which started in August 2003, have borne no fruit. The talks have been locked in a stalemate since the end of the Bush Administration in late 2008. Bush Administration officials had defended the Six-Party Talks by arguing that they need to find out North Korea’s nuclear intention—that is, whether Pyongyang is willing to give up nuclear weapons programs and return to the international non-proliferation regimes. In the aftermath of the second nuclear test, the North’s intention has become obvious.Despite many rhetorical compliments, the Six-Party Talks have revealed their limit as a framework to resolve the North Korean nuclear crisis. North Korea quadrupled nuclear capacities during the talks, conducted two nuclear tests, and secretly provided Syria with an upgraded version of the 5MWe reactor at Yongbyon—a plutonium producing machine. Compared to the mid-1990s, the amount of plutonium the DPRK possesses has increased from 7-12.5 kg to 28.5-49 kg at the end of 2007. The possible number of nuclear warheads also has increased from 1-5 to 5-20 or so, depending on various criteria and technologies. [61] This is the end result of the Six-Party Talks.Such slim prospects of a negotiated resolution justifies preparing for a tailored deterrence architecture that properly reflects the unique security conditions on the Korean peninsula. As Table 1 shows, the essence of the RTDA in Korea is to link a negotiated settlement of the North Korean nuclear crisis with the preparations for reintroducing a few dozen U.S. tactical nuclear weapons into South Korea. Until December 31, 2015, the target date for transfer of wartime OPCON from the United States, a nuclear negotiation in the existing Six-Party Talks or in a new framework should be conducted as the United States and South Korea make preparations for redeploying U.S. tactical nuclear weapons. Once Seoul and Washington declare the dual-track approach, the bilateral nuclear sharing consultations should begin immediately. If the negotiation succeeds and North Korea is denuclearized, the preparations can be immediately halted. If not, the redeployment should be carried out as planned in early 2016. Then, South Korea and the United States will propose mutual nuclear disarmament talks to North Korea, the goal of which would be to exchange the withdrawal of the U.S. tactical nuclear weapons for the denuclearization of North Korea.Table 1: The Dual-Track Approach on the Korean Peninsula Some may argue that the United States will not consent to this dual-track approach since it is contradictory to the new nuclear strategy of the Obama Administration. At first glance, it is indeed a step backward from President Obama’s vision of a world without nuclear weapons. However, the dual-track approach should be seen as a more active scheme to dismantle North Korea’s nuclear weapons programs which is undoubtedly the most significant proliferation threat in the world. This approach is a deliberate attempt for a two-step advance later, overcoming the one-step back now. The dual-track approach is also an effective measure to put the concept of the RTDA into practice—tailoring deterrence capabilities to meet unique security needs of a particular region. That is, as long as nuclear weapons exist in Northeast Asia, ROK-U.S. alliance should remain a nuclear alliance.There is a historical precedent of the dual-track approach. In December 1979, the United States decided to deploy intermediate-range missiles in Western Europe vis-à-vis newly deployed Soviet intermediate-range missiles such as SS-20, SS-4, and SS-5. The United States made a plan to deploy 108 Pershing II missiles and 464 ground-launched cruise missiles in 1983. The decision was a typical dual-track approach intending to barter withdrawal of the deployed Soviet missiles with halting of the planned deployment of U.S. missiles to increase deterrent capabilities in case the barter was not successful.A necessity of nuclear consultation and establishment of NATO-type nuclear sharing mechanism in East Asia was promoted by American experts as well. Two former senior officials of the United States argued that the situation in East Asia today is similar to that of the early 1960s in Western Europe, when some European allies doubted the U.S. will and ability to defend their security. [62] To remedy drawbacks of deterrence, specificity and credibility, they say that NATO established the Nuclear Planning Group and “brought America’s allies to the table on matters such as where, when and how America and the alliance would respond to a Soviet attack” and then, “the allies deployed weapons matched appropriately with the threat of various Soviet systems.” They argued that a similar defensive step is necessary in East Asia and “the U.S. should make strategic defense and nuclear deterrence real enough for allies to feel secure and forgo nuclear weapons themselves.” They proposed that “America and its allies need a Nuclear and Strategic Planning Group for East Asia, starting with Japan and then including other democratic countries.”Conclusion: South Korea’s Alliance Security AssuranceDespite North Korea’s determined efforts to acquire nuclear weapons, South Korea has firmly adhered to its non-nuclear weapon policy since it was first announced in 1990. Geostrategic circumstances on the Korean peninsula, however, tend to provide a strong rationale for the international community to be suspicious of sincerity of South Korea’s non-nuclear weapon policy. North Korea’s nuclear weapons program has only added to the suspicions.Contrary to this traditional wisdom, the North Korean nuclear crisis has actually increased the authenticity of South Korea’s non-nuclear weapon policy. Despite the DPRK’s two nuclear tests in three years, the South Korean Government has shown no hint of changing the current policy. Emotional public voices for the ROK to respond in kind by going nuclear on its own have been calmed by sensible and mature opinions to follow international nonproliferation norms in a responsible manner. The Obama Administration’s reducing role of nuclear weapons will not agitate the resolve to maintain South Korea’s current policy either.South Korea’s commitment to non-nuclear weapon policy is on a par with its commitment to alliance with the United States in two ways. On one hand, U.S. extended deterrence, including the nuclear umbrella, has filled the security vacuum created by the South’s non-nuclear weapon policy. The history of the bilateral alliance proves that the U.S. nuclear umbrella has been efficient and effective in deterring North Korea. On the other hand, as a credible and responsible ally, South Korea is not careless enough to behave in a way that its ally objects to. Therefore, suspicion of South Korea’s non-nuclear weapon policy is outdated and futile and should not cast a shadow over the future partnership of the ROK-U.S. alliance including nuclear energy cooperation. [63] In short, South Korea can provide the United States with alliance security assurance (ASA) and support the U.S. nonproliferation commitments. The alliance security assurance is a U.S. ally’s promise that as an alliance partner under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, it will neither develop nor possess nuclear weapons as long as extended deterrence, including extended nuclear deterrence, is provided.An obstacle to further strengthening the bilateral alliance is the fixation of the American mind-set regarding South Korea. American politicians and bureaucracy both in the military and civilian sectors have a tendency to look at South Korea through an old lens. This fixed view was one of the causes of the strong anti-American sentiments in South Korea during the candle light demonstrations in December 2002. The United States failed to recognize the rapid growth and changes in South Korean society. Such a mistake should not be repeated. The bilateral alliance between Washington and Seoul should move beyond the force of habit of the old days when South Korea strived to rebuild from the rubble of the Korean War. With strong support and assistance from the United States, South Korea has become the first donor-providing nation among the developing countries in the world.Nowadays, South Korean culture, products, technologies, humanitarian assistance, and diplomatic contributions reach out to many parts of the world. In the realm of nuclear nonproliferation, South Korea also is proud of becoming a role model to demonstrate that security can be attained without nuclear weapons, and a responsible and transparent nuclear energy policy has brought prosperity and well-being to its people. Moving beyond the trite perception, stereotyped attitudes, and fixed mindedness, Seoul and Washington need a new vision with long-term perspectives and acute awareness of the rapidly changing security dynamics in Northeast Asia.III. Citations[1] The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the ROK Government or the Korea Institute for National Unification.[2] Brad Glosserman and Ralph Cossa, “U.S.-ROK Relations: a Joint Vision—and Concerns about Commitment,” PacNet, 54-4 (August 2009).[3]“Speech of Secretary of State Cyrus Vance at the 1978 UN Special Session on Disarmament”, UN Document A/S-10/AC.1/30.[4] “Conclusion of Effective International Arrangements to Assure Non-Nuclear Weapon States Against the Use or Threat of Use of Nuclear Weapons”, United Nations General Assembly Security Council Documents S/1995/261 (The Russian Federation), S/1995/262 (The United Kingdom), S/1995/263 (The United States) and S/1995/264 (France).[5]“Conclusion of Effective International Arrangements to Assure Non-Nuclear Weapon States Against the Use or Threat of Use of Nuclear Weapons”, United Nations General Assembly Security Council Document S/1995/265 (China).[6] Nuclear Posture Review Report (Washington, DC, Department of Defense, April 2010).[7] The Obama administration leaves open a slim window of nuclear retaliation in the future case of drastic advance of the biological weapon technologies. The NPR says that “Given the catastrophic potential of biological weapons and the rapid pace of bio-technology development, the United States reserves the right to make any adjustment in the assurance that may be warranted by the evolution and proliferation of the biological weapons threat and U.S. capacities to counter that threat.” Ibid., pp. 16.[8] “DOD’s Nuclear Posture Review Rollout Briefing”, Washington Foreign Press Center (7 April 2010) at <http://www.defense.gov/npr/docs/FPC-_4-7-10_-Nuclear-Posture-Review.pdf>. (searched date: 11 April 2010).[9] “DOD News Briefing with Secretary Gates, Navy Adm. Mullen, Secretary Clinton, and Secretary Chu from the Pentagon”, U.S. Department of Defense (6 April 2010),at <http://www.defense.gov/Transcripts/Transcript.aspx?>. (searched date: 11 April 2010).[10] Sanger, David and Thom Shanker, “Obama’s New Nuclear Strategy is Intended as a Message to Iran and North Korea,” New York Times (6 April 2010).[11] Feaver, Peter, “Obama’s Nuclear Modesty,” New York Times (9 April 2010).Mr. Feaver, a former National Security Council staff member under Presidents Bill Clinton and George Bush, said that “If adversaries believe what is stated in the new Obama doctrine, the umbrella is a bit smaller, with fewer scenarios in both the ‘certain’ and the ‘likely enough’ categories. Thus, when it comes to strategic ambiguity, the critics have a point.”[12] Charles Krauthammer, “Nuclear Posturing, Obama-Style,” Washington Post (9 April 2010), pp. A21.[13] For example, John Bolton said “By further unilaterally limiting the circumstance in which the United States would use nuclear weapons to protect itself and its allies, the Obama administration is in fact increasing international instability, and the risks of future conflict.” Campbell Craig, “Just like Ike (on Deterrence),” New York Times (9 April 2010).[14] James Woolsey, “Too Much Mr. Nice Guy,” New York Times (7 May 2010).[15] Ibid.; Peter Feaver, op. cit., 2010.[16] Thom Shanker and David Sanger, “U.S. to Aid South Korea with Naval Defense Plan,” New York Times (30 May 2010).[17] Park Chang-hee, “A Theoretical Analysis of Asymmetrical Strategies,” Quarterly Journal of Defense Policy Studies, 24-1 (Spring 2008), pp. 179-205.; Park Chang-kwon, “North Korea’s Asymmetrical Strategies and South Korea’s Response,” North Korea (March 2006), pp. 121-132.; Bruce Bechtol Jr., Defiant Failed State: The North Korean Threat to International Society (Potomac Books, 2010); Andrew Scobell and John Sanford, North Korea’s Military Threat: Pyongyang’s Conventional Forces, Weapons of Mass Destruction, and Ballistic Missiles, (Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, April 2007).[18] Bruce Bechtol Jr., The U.S. and South Korea: Challenges and Remedies for Wartime Operation Control (Washington, DC, Center for U.S.-Korea Policy, March 2010).[19] Ibid.[20] The OPCON was agreed to transition on 17 April 2012 between progressive President Roh Moo-hyun and President George Bush in 2007.[21]“Joint Statement of ROK-U.S. Foreign and Defense Ministers’ Meeting on the Occasion of the 60th Anniversary of the Outbreak of the Korean War”, Office of the Spokesman, U.S. Department of State (21 July 2012), at <http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2010/07/144974.htm>. (searched date: 25 July 2012).[22] The Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group, Investigation Result on the Sinking of ROKS “Cheonan” (Seoul: The Ministry of National Defense, 20 May 2010).[23]“Additional Prehearing Questions for James R. Clapper, Jr., Upon his nomination to be Director of National Intelligence”, Select Committee on Intelligence United States Senate (20 July 2010, at <http://www.intelligence.senate.gov/100720/clapperpre.pdf>. (searched date: 30 July 2010).[24] Korean Central News Agency, (9 April 2010).[25] Joint Statement of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the United States of America, (New York, 11 June 1993).[26] Joint Statement of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the United States of America, (Geneva, 19 July 1993).[27] Agreed Statement between the United States of America and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, (Geneva, 12 August 1994).[28] “A speech of the North Korean chief delegate at the third Preparatory Committee Meeting for the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference on 13 September 1994 in Geneva”, FBIS-EAS-94-184 (22 September 1994).[29] FBIS-EAS-94-196 (11 October 1994).[30] Agreed Framework between the United States of America and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, (Geneva, 21 October 1994).[31] Ibid.[32] It is said that “We would provide a ‘negative security assurance’ that would pledge non-use of nuclear weapons against North Korea under certain defined circumstances as long as it remains a member in good standing of the NPT, as we have provided for other members of the NPT.” “Fact Sheet: U.S./DPRK Talks”, Department of State (21 October 1994), pp. 2.[33] Arms Control Today, 24-1 (January/February 1994), pp. 21.[34] “Korean Nuclear Agreement Resolution (Draft)”, 104th Congress 1st Session, (January 1995).[35] American Security Council Foundation, “The North Korean Nuclear Agreement: A Clear and Present Danger,” National Security Analysis (November 1994), pp. 15[36] The author had this discussion with General Cushman at a seminar held by the Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability in Honolulu, 19 July 1994.[37] Dunbar Lockwood, “New Nuclear Posture Review Shows Little Change in Policies,” Arms Control Today, 24-9 (November 1994), pp. 27.[38] The U.S.-DPRK Joint Communiqué, (Washington, D.C., 12 October 2000).[39] “Text: Powell Opening Statement before Senate Foreign Relations Committee” (17 January 2001), at <http://www.usinfo.state.gov>. (searched date: 2 March 2001).[40] “Secretary of State Collin Powell’s Hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the Fiscal Year 2002 Foreign Operations Budget”, Federal News Service (8 March 2001).[41] “Remarks by President Bush and President Kim Dae-Jung of South Korea”, Office of the Press Secretary, the White House (7 March 2001), at <https://nautilus.org>. (searched date: 9 March 2001).[42] House International Relations Committee Chairman Henry Hyde, House Republican Policy Committee Chairman Christopher Cox and Rep. Edward Markey sent a letter to President Bush on 2 March 2001. Steven Mufson, “Flexibility Urged on N. Korea,” Washington Post (3 March 2001), pp. A16.[43] “September 19th Joint Agreement at the 4th Round of the Six-Party Talks”, Beijing, (19 September 2005).[44] North Korea Advisory Group, “Report to the Speaker U.S. House of Representatives) (November 1999), at <http://www.house.gov/international_relations/nkag/report.htm>. (searched date: 5 December 1999).

Some may argue that the United States will not consent to this dual-track approach since it is contradictory to the new nuclear strategy of the Obama Administration. At first glance, it is indeed a step backward from President Obama’s vision of a world without nuclear weapons. However, the dual-track approach should be seen as a more active scheme to dismantle North Korea’s nuclear weapons programs which is undoubtedly the most significant proliferation threat in the world. This approach is a deliberate attempt for a two-step advance later, overcoming the one-step back now. The dual-track approach is also an effective measure to put the concept of the RTDA into practice—tailoring deterrence capabilities to meet unique security needs of a particular region. That is, as long as nuclear weapons exist in Northeast Asia, ROK-U.S. alliance should remain a nuclear alliance.There is a historical precedent of the dual-track approach. In December 1979, the United States decided to deploy intermediate-range missiles in Western Europe vis-à-vis newly deployed Soviet intermediate-range missiles such as SS-20, SS-4, and SS-5. The United States made a plan to deploy 108 Pershing II missiles and 464 ground-launched cruise missiles in 1983. The decision was a typical dual-track approach intending to barter withdrawal of the deployed Soviet missiles with halting of the planned deployment of U.S. missiles to increase deterrent capabilities in case the barter was not successful.A necessity of nuclear consultation and establishment of NATO-type nuclear sharing mechanism in East Asia was promoted by American experts as well. Two former senior officials of the United States argued that the situation in East Asia today is similar to that of the early 1960s in Western Europe, when some European allies doubted the U.S. will and ability to defend their security. [62] To remedy drawbacks of deterrence, specificity and credibility, they say that NATO established the Nuclear Planning Group and “brought America’s allies to the table on matters such as where, when and how America and the alliance would respond to a Soviet attack” and then, “the allies deployed weapons matched appropriately with the threat of various Soviet systems.” They argued that a similar defensive step is necessary in East Asia and “the U.S. should make strategic defense and nuclear deterrence real enough for allies to feel secure and forgo nuclear weapons themselves.” They proposed that “America and its allies need a Nuclear and Strategic Planning Group for East Asia, starting with Japan and then including other democratic countries.”Conclusion: South Korea’s Alliance Security AssuranceDespite North Korea’s determined efforts to acquire nuclear weapons, South Korea has firmly adhered to its non-nuclear weapon policy since it was first announced in 1990. Geostrategic circumstances on the Korean peninsula, however, tend to provide a strong rationale for the international community to be suspicious of sincerity of South Korea’s non-nuclear weapon policy. North Korea’s nuclear weapons program has only added to the suspicions.Contrary to this traditional wisdom, the North Korean nuclear crisis has actually increased the authenticity of South Korea’s non-nuclear weapon policy. Despite the DPRK’s two nuclear tests in three years, the South Korean Government has shown no hint of changing the current policy. Emotional public voices for the ROK to respond in kind by going nuclear on its own have been calmed by sensible and mature opinions to follow international nonproliferation norms in a responsible manner. The Obama Administration’s reducing role of nuclear weapons will not agitate the resolve to maintain South Korea’s current policy either.South Korea’s commitment to non-nuclear weapon policy is on a par with its commitment to alliance with the United States in two ways. On one hand, U.S. extended deterrence, including the nuclear umbrella, has filled the security vacuum created by the South’s non-nuclear weapon policy. The history of the bilateral alliance proves that the U.S. nuclear umbrella has been efficient and effective in deterring North Korea. On the other hand, as a credible and responsible ally, South Korea is not careless enough to behave in a way that its ally objects to. Therefore, suspicion of South Korea’s non-nuclear weapon policy is outdated and futile and should not cast a shadow over the future partnership of the ROK-U.S. alliance including nuclear energy cooperation. [63] In short, South Korea can provide the United States with alliance security assurance (ASA) and support the U.S. nonproliferation commitments. The alliance security assurance is a U.S. ally’s promise that as an alliance partner under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, it will neither develop nor possess nuclear weapons as long as extended deterrence, including extended nuclear deterrence, is provided.An obstacle to further strengthening the bilateral alliance is the fixation of the American mind-set regarding South Korea. American politicians and bureaucracy both in the military and civilian sectors have a tendency to look at South Korea through an old lens. This fixed view was one of the causes of the strong anti-American sentiments in South Korea during the candle light demonstrations in December 2002. The United States failed to recognize the rapid growth and changes in South Korean society. Such a mistake should not be repeated. The bilateral alliance between Washington and Seoul should move beyond the force of habit of the old days when South Korea strived to rebuild from the rubble of the Korean War. With strong support and assistance from the United States, South Korea has become the first donor-providing nation among the developing countries in the world.Nowadays, South Korean culture, products, technologies, humanitarian assistance, and diplomatic contributions reach out to many parts of the world. In the realm of nuclear nonproliferation, South Korea also is proud of becoming a role model to demonstrate that security can be attained without nuclear weapons, and a responsible and transparent nuclear energy policy has brought prosperity and well-being to its people. Moving beyond the trite perception, stereotyped attitudes, and fixed mindedness, Seoul and Washington need a new vision with long-term perspectives and acute awareness of the rapidly changing security dynamics in Northeast Asia.III. Citations[1] The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the ROK Government or the Korea Institute for National Unification.[2] Brad Glosserman and Ralph Cossa, “U.S.-ROK Relations: a Joint Vision—and Concerns about Commitment,” PacNet, 54-4 (August 2009).[3]“Speech of Secretary of State Cyrus Vance at the 1978 UN Special Session on Disarmament”, UN Document A/S-10/AC.1/30.[4] “Conclusion of Effective International Arrangements to Assure Non-Nuclear Weapon States Against the Use or Threat of Use of Nuclear Weapons”, United Nations General Assembly Security Council Documents S/1995/261 (The Russian Federation), S/1995/262 (The United Kingdom), S/1995/263 (The United States) and S/1995/264 (France).[5]“Conclusion of Effective International Arrangements to Assure Non-Nuclear Weapon States Against the Use or Threat of Use of Nuclear Weapons”, United Nations General Assembly Security Council Document S/1995/265 (China).[6] Nuclear Posture Review Report (Washington, DC, Department of Defense, April 2010).[7] The Obama administration leaves open a slim window of nuclear retaliation in the future case of drastic advance of the biological weapon technologies. The NPR says that “Given the catastrophic potential of biological weapons and the rapid pace of bio-technology development, the United States reserves the right to make any adjustment in the assurance that may be warranted by the evolution and proliferation of the biological weapons threat and U.S. capacities to counter that threat.” Ibid., pp. 16.[8] “DOD’s Nuclear Posture Review Rollout Briefing”, Washington Foreign Press Center (7 April 2010) at <http://www.defense.gov/npr/docs/FPC-_4-7-10_-Nuclear-Posture-Review.pdf>. (searched date: 11 April 2010).[9] “DOD News Briefing with Secretary Gates, Navy Adm. Mullen, Secretary Clinton, and Secretary Chu from the Pentagon”, U.S. Department of Defense (6 April 2010),at <http://www.defense.gov/Transcripts/Transcript.aspx?>. (searched date: 11 April 2010).[10] Sanger, David and Thom Shanker, “Obama’s New Nuclear Strategy is Intended as a Message to Iran and North Korea,” New York Times (6 April 2010).[11] Feaver, Peter, “Obama’s Nuclear Modesty,” New York Times (9 April 2010).Mr. Feaver, a former National Security Council staff member under Presidents Bill Clinton and George Bush, said that “If adversaries believe what is stated in the new Obama doctrine, the umbrella is a bit smaller, with fewer scenarios in both the ‘certain’ and the ‘likely enough’ categories. Thus, when it comes to strategic ambiguity, the critics have a point.”[12] Charles Krauthammer, “Nuclear Posturing, Obama-Style,” Washington Post (9 April 2010), pp. A21.[13] For example, John Bolton said “By further unilaterally limiting the circumstance in which the United States would use nuclear weapons to protect itself and its allies, the Obama administration is in fact increasing international instability, and the risks of future conflict.” Campbell Craig, “Just like Ike (on Deterrence),” New York Times (9 April 2010).[14] James Woolsey, “Too Much Mr. Nice Guy,” New York Times (7 May 2010).[15] Ibid.; Peter Feaver, op. cit., 2010.[16] Thom Shanker and David Sanger, “U.S. to Aid South Korea with Naval Defense Plan,” New York Times (30 May 2010).[17] Park Chang-hee, “A Theoretical Analysis of Asymmetrical Strategies,” Quarterly Journal of Defense Policy Studies, 24-1 (Spring 2008), pp. 179-205.; Park Chang-kwon, “North Korea’s Asymmetrical Strategies and South Korea’s Response,” North Korea (March 2006), pp. 121-132.; Bruce Bechtol Jr., Defiant Failed State: The North Korean Threat to International Society (Potomac Books, 2010); Andrew Scobell and John Sanford, North Korea’s Military Threat: Pyongyang’s Conventional Forces, Weapons of Mass Destruction, and Ballistic Missiles, (Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, April 2007).[18] Bruce Bechtol Jr., The U.S. and South Korea: Challenges and Remedies for Wartime Operation Control (Washington, DC, Center for U.S.-Korea Policy, March 2010).[19] Ibid.[20] The OPCON was agreed to transition on 17 April 2012 between progressive President Roh Moo-hyun and President George Bush in 2007.[21]“Joint Statement of ROK-U.S. Foreign and Defense Ministers’ Meeting on the Occasion of the 60th Anniversary of the Outbreak of the Korean War”, Office of the Spokesman, U.S. Department of State (21 July 2012), at <http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2010/07/144974.htm>. (searched date: 25 July 2012).[22] The Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group, Investigation Result on the Sinking of ROKS “Cheonan” (Seoul: The Ministry of National Defense, 20 May 2010).[23]“Additional Prehearing Questions for James R. Clapper, Jr., Upon his nomination to be Director of National Intelligence”, Select Committee on Intelligence United States Senate (20 July 2010, at <http://www.intelligence.senate.gov/100720/clapperpre.pdf>. (searched date: 30 July 2010).[24] Korean Central News Agency, (9 April 2010).[25] Joint Statement of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the United States of America, (New York, 11 June 1993).[26] Joint Statement of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the United States of America, (Geneva, 19 July 1993).[27] Agreed Statement between the United States of America and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, (Geneva, 12 August 1994).[28] “A speech of the North Korean chief delegate at the third Preparatory Committee Meeting for the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference on 13 September 1994 in Geneva”, FBIS-EAS-94-184 (22 September 1994).[29] FBIS-EAS-94-196 (11 October 1994).[30] Agreed Framework between the United States of America and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, (Geneva, 21 October 1994).[31] Ibid.[32] It is said that “We would provide a ‘negative security assurance’ that would pledge non-use of nuclear weapons against North Korea under certain defined circumstances as long as it remains a member in good standing of the NPT, as we have provided for other members of the NPT.” “Fact Sheet: U.S./DPRK Talks”, Department of State (21 October 1994), pp. 2.[33] Arms Control Today, 24-1 (January/February 1994), pp. 21.[34] “Korean Nuclear Agreement Resolution (Draft)”, 104th Congress 1st Session, (January 1995).[35] American Security Council Foundation, “The North Korean Nuclear Agreement: A Clear and Present Danger,” National Security Analysis (November 1994), pp. 15[36] The author had this discussion with General Cushman at a seminar held by the Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability in Honolulu, 19 July 1994.[37] Dunbar Lockwood, “New Nuclear Posture Review Shows Little Change in Policies,” Arms Control Today, 24-9 (November 1994), pp. 27.[38] The U.S.-DPRK Joint Communiqué, (Washington, D.C., 12 October 2000).[39] “Text: Powell Opening Statement before Senate Foreign Relations Committee” (17 January 2001), at <http://www.usinfo.state.gov>. (searched date: 2 March 2001).[40] “Secretary of State Collin Powell’s Hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the Fiscal Year 2002 Foreign Operations Budget”, Federal News Service (8 March 2001).[41] “Remarks by President Bush and President Kim Dae-Jung of South Korea”, Office of the Press Secretary, the White House (7 March 2001), at <https://nautilus.org>. (searched date: 9 March 2001).[42] House International Relations Committee Chairman Henry Hyde, House Republican Policy Committee Chairman Christopher Cox and Rep. Edward Markey sent a letter to President Bush on 2 March 2001. Steven Mufson, “Flexibility Urged on N. Korea,” Washington Post (3 March 2001), pp. A16.[43] “September 19th Joint Agreement at the 4th Round of the Six-Party Talks”, Beijing, (19 September 2005).[44] North Korea Advisory Group, “Report to the Speaker U.S. House of Representatives) (November 1999), at <http://www.house.gov/international_relations/nkag/report.htm>. (searched date: 5 December 1999).