The Status Quo Isn’t Working: A Nuke-Free Zone Is Needed Now

Policy Forum 10-051: October 6th, 2010

Peter Hayes

——————–

CONTENTS

I. Introduction

II. Article by Peter Hayes

III. Suggested Readings

IV. Regional Nuclear Weapon-Free Zones

V. Nautilus invites your responses

This paper is part of the Nautilus Institute’s Korea-Japan Nuclear Weapon Free Zone Initiative.

This article was originally published by Global Asia.

I. Introduction

P

eter Hayes, Executive Director of the Nautilus Institute, writes, “One thing is clear about past attempts to denuclearize North Korea: They have been an abysmal failure. They have not afforded Pyongyang the sense of security it needs to take real steps to give up its nuclear weapons ambitions. The idea of a South Korea-Japan nuclear weapon-free zone provides a fresh approach that might just work.”

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on contentious topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Article by Peter Hayes

-“The Status Quo Isn’t Working: A Nuke-Free Zone Is Needed Now”

By Peter Hayes

A South Korea-Japan Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone is an attractive regional security concept compared with either the status quo or a future for Northeast Asia without such a zone. It should be in force by 2012.

Why now? First, North Korea is developing more and better nuclear weapons as fast as possible. It can forge nuclear alliances in ways that cannot be easily stopped. Urgency is needed to slow, freeze and reverse this process. Reaffirming the American commitment to provide extended nuclear deterrence to the region did not deter North Korea from continuing to arm and test nuclear weapons. If anything, these nuclear threats, especially those in the April 2010 US Nuclear Posture Review, made the situation worse.

Second, the six-party talks are moribund. A new framework is needed to manage the insecurity created by North Korea’s nuclear weapons and the risk of nuclear war in Korea.

Third, the White House is comfortable with containment, at least until it fails catastrophically. Nothing indicates that US President Barack Obama will change his policy of isolating, shaming and squeezing North Korea. This myopic policy enables the North to continue a “nuclear succession” in which Kim Jong-il bequeaths a nuclear-armed nation to a new generation of leaders.

Fourth, North Korea demoted the US from being the primary target of its nuclear threat in early 2009. Until then, the North tried to compel the US to change its policies via nuclear threat, and failed. Since then, North Korea has focused the threat on Seoul (while keeping some threat in reserve to deter an American attack). In March 2010, it sank the South Korean warship Cheonan, thereby demonstrating that it intends to exploit the power potential of its nuclear weapons, including risking full-scale nuclear war in Korea. The peninsula has not been in free-fall towards war like this for decades. Only China’s intercession and engagement of North Korea has stabilized the situation. For South Korea and Japan, becoming beholden to China to restrain North Korea is a poor substitute for American leadership.

North Korea and the Zone

Is there an alternative to allowing North Korea’s nuclear breakout to accelerate, leaving the region adrift strategically?

The fundamental reason that North Korea developed nuclear weapons is because over two decades of talks, the US did not make a sovereign, reliable commitment not to use nuclear weapons against the North if it denuclearized.

Until April this year, the US told North Korea that only if it fully complied with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards would it guarantee not to use nuclear weapons against it — but then voided this guarantee because North Korea was allied with a nuclear weapons state, China. In effect, the US said that the only way to obtain a meaningful negative security assurance was if it abandoned its military alliance with China — even if it fully denuclearized. Ironically, the US removed this exclusion in the April 2010 US Nuclear Posture Review to induce the North to return to talks, but by then, it was too late — about two decades too late.

If North Korea is to give up its nuclear weapons, it will require a sovereign American guarantee that the US is not targeting the North with nuclear weapons. The only way that North Korea can obtain that is through a binding treaty commitment approved by the US Senate — something the US has never put on the table. In contrast, a nuclear weapon-free zone would provide North Korea with some real security instead of a strategic dead-end. It should have been proposed much earlier, but it is not too late to do so.

Benefits of the Zone

The zone could solve a number of linked and seemingly intractable security problems in Northeast Asia.

First and foremost, it would offer the only peaceful path to eliminate North Korea’s nuclear weapons. There are two ways for the North to join the zone. One is to encourage North Korea to sign the zone treaty at the outset, but allow it to waive some of the nuclear-free requirements until it is secure enough to do so. This is what Argentina and Brazil did in the Latin American NWFZ treaty. They took 18 years to remove their waivers, but they eventually did. This approach would recognize North Korea as a legitimate state, but deny it nuclear weapons state-status, and calibrate its gains from joining the zone to the pace of its nuclear disarmament, especially guarantees from nuclear weapons states not to target it.

By offering North Korea “co-founder” status in such a zone, South Korea might bring the North into the tent for the Global Nuclear Summit in May 2012 in Seoul, at which time governments might announce a regional commission to study the zone concept.

The other way is to simply leave the door open until the North decides to disarm and join the zone for its own reasons (most likely the cumulative costs of nuclear outlaw status or a change in leadership); or it collapses, at which time the zone would cover a unified Korea. Either way, nuclear extended deterrence would continue to operate, albeit weakly, for US allies; and along with China and Russia, North Korea would continue to be an American nuclear target for as long as it remained nuclear-armed. It would be vastly preferable to have Pyongyang join the zone camp from the outset, because North Korea would reaffirm its intention to denuclearize. The process of implementing the zone — in conjunction with separate negotiations with the US and China — would leverage the North into eventual compliance.

If North Korea remains a nuclear outlaw state outside the zone, possibly for many years, it would continue to pose a nuclear threat. Although the zone would devalue the symbolic power of North Korea’s nuclear weapons, it would not offer a built-in means to redress continuing nuclear threats, let alone actual use by the North.

Today, the US can only deliver a small number of nuclear weapons against North Korea by flying strategic bombers from the US mainland to the North and back with mid-air refueling. All other options are constrained or incredible. By the same token, the only realistic use North Korea could make now of its nuclear weapons is as land mines in the North itself — hardly a scenario in which a US nuclear strike would be justified.

Given the current state of American nuclear options and North Korea’s nuclear threat, the zone would employ conventional deterrence to counter the North’s nuclear threat for as long as needed; and conventional forces would be used to retaliate against nuclear aggression. The US and South Korean military have long planned to deal with the North’s military threat, including the threat of nuclear attack, with superior combined conventional forces. This would continue with or without North Korea in the zone.

If North Korea were ever to use nuclear weapons against the zone, then almost certainly it would be dismembered by conventional forces rather than destroyed by nuclear retaliation. The nuclear weapons states would want to restore the global nuclear taboo as well as minimize civilian casualties and nuclear fallout in the zone. Similarly, with or without the zone, bilateral and multilateral negotiations would continue with North Korea over the pace of its nuclear disarmament. But as noted above, only the zone offers a clear way for the North to disarm and in return get sovereign guarantees from nuclear weapons states that it will not be attacked by nuclear weapons — a necessary condition for North Korea to disarm.

A second problem the zone would address is that it would lock Japan and South Korea into permanent non-nuclear status, without hedging. Currently, both countries have virtual nuclear weapons capacity that could be realized in months (for Japan) or a few years (for South Korea). The nuclear weapons potential of Japan and to a lesser extent South Korea (before or after unification) is of great concern to China, especially if these were independent nuclear forces. The zone would settle this issue permanently.

Third, the zone would replace China’s vague “no first-use” declaration with a stronger commitment to not target South Korea or Japan — so long as US or Russian nuclear forces do not use the zone to target or attack China. Moreover, if Russia ratifies and provides a similar guarantee, then the strategic rationale for keeping strategic nuclear bombers or naval-nuclear forces in the Russian Far East become dubious and could lead to their removal — a side benefit of the zone.

Fourth, the zone would establish an enduring, long-term security institution in the region based on cooperation and transparency. By making Japanese and South Korean security inter- dependent, it would create a shared non-nuclear narrative based on stringent monitoring and verification. The zone would enable the two countries to eliminate nuclear weapons from their national security calculus, further historical reconciliation, advance a common security agenda, promote economic interdependence (especially on the nuclear fuel cycle) and stimulate technological sharing (especially on space launch cooperation).

Fifth, the zone would ensure that US conventional forces remain anchored in the Korean Peninsula for the foreseeable future, even after reunification. Even a reunified Korea would need US troops to offset the huge Chinese army, thereby creating a permanent conventional buffer force between China and Japan.

Sixth, the zone would impel US allies and adversaries to adjust their expectations to accord with the condition of US nuclear forces today. US tactical and theater nuclear forces were removed from the region in February 1992, including the submarine-launched cruise missiles which were home-stored and only available in extremis, and even then only after crews were recertified, missiles and warheads loaded and moved into the western Pacific with as much as a 30-day delay!

In fact, the US has already effectively “recessed” nuclear extended deterrence. Residual American nuclear forces are in poor shape. Allied perceptions have still to catch up with this reality, although most strategists know that conventional deterrence is far more important for practical security management than nuclear forces. The zone will also be more amenable to what Japanese security analysts call “dynamic deterrence” in contrast to the Cold War-era “static deterrence,” wherein Japanese military forces were home-bound and subordinate to American conventional forces.

Seventh, the zone would demonstrate that the US intends to share management of security issues in the region not only with its allies, but also with China, Russia and even North Korea. This shift to multilateralism would also recast the US-Japan alliance from a primarily military to a primarily political axis of great power — which is consistent with the views of Japan’s new political leadership on the need to construct a cooperative strategic relationship with China.

Conclusion

Overall, the zone would herald a shift in the role of US forward-deployed forces from a purely partisan to partly pivotal deterrent — thereby preserving both its hegemonic role and restoring its geopolitical leadership.

The US could also link the zone to global strategic nuclear disarmament. For example, given that the zone would eliminate the threat of a nuclear-armed Japan, the US might make its support for the zone contingent on China participating in strategic arms limitation talks once Russian and American forces each reach 1,000 warheads. In the unlikely event that China tries instead to block the zone, then the US could threaten to share nuclear weapons planning with its East Asian allies, a prospect that would bring China to the table.

Finally, the zone would be the first to cover the territory of OECD states in the northern hemisphere. It would significantly reinforce an important global nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament norm. Thus, not only would the zone make the region safer, it would have also contributed to global security.

The August 6, 1945 nuclear explosion over Hiroshima city fused the fates of 70,000 Koreans who were killed or injured with that of asimilar number of Japanese civilians also killed or injured. On August 6, 2012, it would be fitting if hibakusha from Japan, wonpok huischanga from the two Koreas, and any survivors from other countries who are still alive, were to welcome the six heads of state to Hiroshima to sign the zone treaty.

III. Suggested Readings

S.W. Cheon, T. Suzuki, “The Tripartite Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone in Northeast Asia: a Long-Term Objective of the Six Party Talks,” International Journal of Korean Studies, 12, 2, 2003, pp. 41-68.

J. Endicott, “Limited Nuclear Weapon-Free Zones: The Time Has Come”, Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 20:1, March 2008.

H. Umebayashi, “Towards a Northeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone”, Japan Focus, August 11 2005,

http://japanfocus.org/products/topdf/1784

P. Hayes, “Extended Nuclear Deterrence, Global Abolition, and Korea,” The Asia Pacific Journal, No. 50. 2009, December 14, 2009, at:

http://japanfocus.org/-Peter-Hayes/3268

P. Hayes and M. Hamel-Green, “The path not taken, the way still open: Denuclearizing the Korean peninsula and Northeast Asia,” Austral Peace and Security Network Special Report 09-09S, 14 December 2009.

J. Lewis, “Rethinking Extended Deterrence in Northeast Asia,” paper to Nautilus Institute research workshop “Strong connections: Australia-Korea strategic relations — past, present and future” Seoul, 15-16 June, 2010, at:

https://nautilus.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Lewis1.pdf

S. Ogawa, “Link Japanese and Koreans in a Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone,” International Herald Tribune, August 29, 1997, at: h

ttp://www.nytimes.com/1997/08/29/opinion/29iht-edskin.t.html?pagewanted=1

S. Parrish and J. du Preez, Nuclear Weapon-Free Zones: Still a Useful Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Tool? Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission, Research Paper No.6, no date, at:

http://www.wmdcommission.org/files/No6-ParrishDuPreez-Final.pdf

J. Redick, Nuclear Illusions: Argentina and Brazil, Occasional Paper No. 25, Stimson Center, Washington DC, 1995.

United Nations, “Establishment of nuclear weapon-free zones on the basis of arrangements freely arrived at among the States of the region concerned,” Annex 1, Report of the Disarmament Commission, General Assembly, 54th session, Supplement No. 42 (A/54/42), United Nations, New York, 1999, p. 7, at:

http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N99/132/20/PDF/N9913220.pdf?OpenElement

IV. Regional Nuclear Weapon-Free Zones

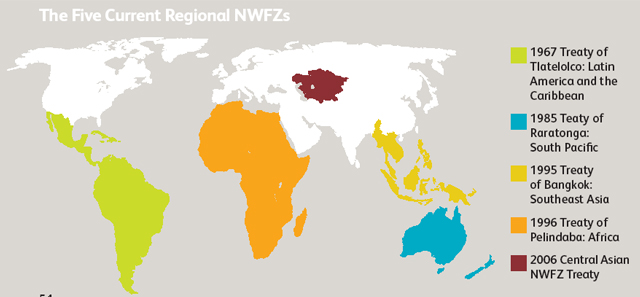

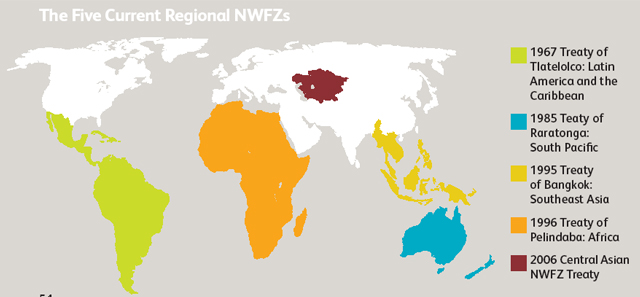

The central idea underlying a nuclear weapon-free zone (NWFZ) is that one or more states commit to the total exclusion of any nuclear weapons from their territories. This idea was anticipated in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and was sanctioned by the UN General Assembly in 1975, recognizing that new nuclear proliferation was rooted in regional conflicts. Five treaty-based, fully-fledged NWFZs are in force, as well as a range of other treaties and national declarations banning nuclear weapons from specific territories.

A total 112 states are party to NWFZ treaties covering a large part of the Northern and almost the entire Southern Hemisphere. They are an established and legitimate instrument used by states to realize nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament policy goals. As the UN Disarmament Commission concluded in 1999, “Nuclear weapon-free zones are an important disarmament tool which contributes to the primary objective of strengthening regional peace and security and, by extension, international peace and security. They are also considered to be important regional confidence-building measures.” The International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament concurred, saying they “have made, and continue to make, a very important contribution to nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament,” and recommended both their strengthening and the establishment of new zones.

These NWFZs vary substantially in relation to critical elements — for example, some (such as the South Pacific treaty) do not commit Nuclear Weapons States (NWSs) party to the NWFZ not to fire nuclear weapons into or out of the zone. None but the Southeast Asia treaty contains any enforcement mechanism should an NWS party to an NWFZ treaty transgress its zonal obligations. The South Pacific and African NWFZs, like others, prohibit not only nuclear weapons, but also disassembled or partly assembled weapons.

In principle, NWFZs still permit peaceful nuclear devices and even actual peaceful nuclear explosions within a NWFZ, even though these are technically indistinguishable from nuclear weapons and nuclear tests or attacks. Only the Southeast Asian and Latin American zones include marine exclusive economic zones in the territory the zone covers. The issue of transit by air or sea by nuclear-capable ships or aircraft that may carry nuclear weapons remains contentious and ambiguous in all the zones.

In South Korea, conceptual discussions of NWFZs have been limited mostly to an inter-Korean zone reviving or replacing the 1992 Joint Declaration. In Japan, the proposals have originated from a focus on overcoming the limits of Japan’s current non-nuclear principles, resulting in proposed zones that cover the whole Northeast Asian region. Of these, the “3+3” regional zone covering the two Koreas and Japan plus three nuclear weapons states (the United States, Russia, and China) has gained the most traction in the region. However, Japan has not supported officially a regional NWFZ in Northeast Asia, although current Foreign Minister Katsuya Okada reportedly favors the concept.

V. Nautilus invites your responses

The Northeast Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this essay. Please send responses to: bscott@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.

The NAPSNet Policy Forum provides expert analysis of contemporary peace and security issues in Northeast Asia. As always, we invite your responses to this report and hope you will take the opportunity to participate in discussion of the analysis.

The NAPSNet Policy Forum provides expert analysis of contemporary peace and security issues in Northeast Asia. As always, we invite your responses to this report and hope you will take the opportunity to participate in discussion of the analysis.

eter Hayes, Executive Director of the Nautilus Institute, writes, “One thing is clear about past attempts to denuclearize North Korea: They have been an abysmal failure. They have not afforded Pyongyang the sense of security it needs to take real steps to give up its nuclear weapons ambitions. The idea of a South Korea-Japan nuclear weapon-free zone provides a fresh approach that might just work.”

eter Hayes, Executive Director of the Nautilus Institute, writes, “One thing is clear about past attempts to denuclearize North Korea: They have been an abysmal failure. They have not afforded Pyongyang the sense of security it needs to take real steps to give up its nuclear weapons ambitions. The idea of a South Korea-Japan nuclear weapon-free zone provides a fresh approach that might just work.”

![]() The NAPSNet Policy Forum provides expert analysis of contemporary peace and security issues in Northeast Asia. As always, we invite your responses to this report and hope you will take the opportunity to participate in discussion of the analysis.

The NAPSNet Policy Forum provides expert analysis of contemporary peace and security issues in Northeast Asia. As always, we invite your responses to this report and hope you will take the opportunity to participate in discussion of the analysis.