Ending Somalian Piracy: Pitfalls and Possibilities of Australian Naval Intervention and Long-Term Human Security Policy Initiatives

Policy Forum Online 09-010A: February 5th, 2009

By Carolin Liss

CONTENTS

IV. Nautilus invites your responses

I. Introduction

Carolin Liss, a Post-doctoral Research Fellow at the Asia Research Centre at Murdoch University, writes, “patrolling pirate infested waters will not address the underlying root causes of modern day piracy, which include illegal and over-fishing, lax (international) maritime regulations, ineffective and corrupt government forces, armed conflict and widespread poverty… It is therefore important for Australia, and other countries already involved in combating Somali piracy, to understand that the current international patrols have to be seen as a first step in a longer process.”

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Nautilus Institute. Readers should note that Nautilus seeks a diversity of views and opinions on contentious topics in order to identify common ground.

II. Article by Carolin Liss

– “Ending Somalian Piracy: Pitfalls and Possibilities of Australian Naval Intervention and Long-Term Human Security Policy Initiatives”

By Carolin Liss

The world’s most blatant pirate attacks are currently taking place off the coast of Somalia. In the past 12 months, more than 100 ships were attacked in this dangerous area. These attacks included more than 40 hijackings of merchant and fishing vessels, with the pirates receiving millions of US dollars in ransom money for kidnapped crew and hijacked vessels. When attacks on vessels off the coast of Somalia became more frequent and serious in nature, international concern about the safety of ships and crews passing the Horn of Africa grew. As a result, nations from around the world have sent warships to combat piracy in the area. In January 2009, Australian Defence Force Chief, Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston, voiced the possibility of Australian involvement in the fight against Somali pirates. This paper discusses the possible benefits and disadvantages of Australian participation in an international, UN approved, anti-piracy task-force operating in the Gulf of Aden and off the Horn of Africa.

The Problem: Piracy in Somalia

The number and scale of pirate attacks currently occurring in the Gulf of Aden and off the Horn of Africa are unprecedented and pose a serious threat to international shipping. Over the past several months, pirates have attacked UN aid ships, hijacked merchant and fishing vessels, held crew hostage and collected millions in US dollars in ransom payments. Most attacks occurred in the Gulf of Aden and off the coast of Somalia, with pirate gangs using mother ships to conduct attacks too far from the coast for speedboats to reach. At the start of 2009, pirates in the area hold up to 15 ships at a time while ransom negotiations between shipowners and pirates take place. The negotiation processes can take months, with the crew held hostage but generally treated well. Once a ransom is paid, the crew and vessel are released and the pirates hijack a new vessel.

With their newfound wealth, the pirates are believed to buy additional boats and weapons for future attacks and to have built houses and bought expensive cars. Shops catering to the pirates have sprung up along the coast in areas where hijacked ships are held, providing supplies for the pirates and hostages. [1] Over the past several weeks some pirates have freely given interviews to the international media, explaining their motives and aims. Their activities, they claim, started as a protective measure against illegal fishing in their waters, which depleted fish stocks in the area, robbing local fishers of their income and livelihood. Over time their activities changed and more and more international merchant vessels were targeted after substantial ransoms were paid. According to the pirates, their activities are driven by poverty, with some perpetrators expressing the hope that their attacks on international shipping will attract attention to the poverty and conflict in Somalia and the suffering of the local population. They stress, however, that they are interested in ransom payments only and have so far not voiced political demands in exchange for hijacked ships, except for the release of captured pirates. [2]

Among the vessels attacked by pirates in recent months were the Ukrainian freighter La Faina , carrying 33 combat tanks and other weaponry, which was hijacked on the 25 September 2008, and the super tanker Sirius Star , taken in mid-November. The Sirius Star , a new ship worth approximately US$150 million, is the largest vessel ever taken by pirates and was carrying a cargo of crude oil with a value of US$100 million at the time of attack. While the Sirius Star has been released in January 2009 after a ransom of reportedly US$3 million was paid, the hijacking of the super tanker clearly demonstrated the capacity of the Somali sea-robbers to attack ships of any size. Furthermore, attacks in recent weeks, such as the hijacking of the tanker Sea Princess II on January 2, show that current efforts to combat piracy in the region are not sufficient to prevent major attacks – despite the involvement of naval forces from countries around the world. [3]

Responses

The vast majority of pirate attacks around the world occur in national waters, and piracy is therefore often considered a problem that should be addressed by the state (or states) where attacks take place.

Somalia, however, does not at present have the capacity to secure its waters. The country has often been described as a failed state, and has had no effective government in place since 1991. Indeed, after the end of the Cold War, the country’s central government collapsed and Somalia has been ruled by a succession of varying coalitions of politicians and local warlords. With weapons widely available, armed conflict and violence has been a constant component of ‘politics’ in Somalia. Famine and other natural and manmade disasters have been a further long-term burden for the country’s population. International organisations, such as the UN, and various countries from within and beyond Africa have, throughout this period, been involved in Somali politics and conflicts and have provided limited humanitarian assistance.

Over the years, efforts were made by local and international governments and interest groups to stabilise the political situation in Somalia, with a succession of interim governments in place. In early 2006, with the fragile Transnational Federal Government (TFG) in power, fighting between the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC) and the US-supported Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter Terrorism (ARPCT) erupted. The UIC gained control over Mogadishu and large parts of the south, and a ceasefire agreement was reached in June 2006. While the UIC held power, pirate attacks – which had been a concern in Somalia – ceased, as UIC fighters defeated armed groups involved in piracy and announced that pirates would be punished under Sharia law. [4] However, the situation deteriorated again when US-backed Ethiopian troops entered the conflict in support of the TFG, gaining the upper hand in December. The defeat of the UIC did not, however, bring peace or stability, despite a UN Security Council-authorised African Union peacekeeping mission, starting in February 2007. In fact, the continued presence of Ethiopian troops fuelled further unrest in a country already plagued by internal unrest and clan-based and political rivalry.

In early 2008, the security situation deteriorated once again with escalating armed conflict between Islamist insurgents, Ethiopian troops and other factions in addition to US air strikes on Islamist bases as part of the war on terrorism. [5] Today, the situation is still volatile, with the country’s President Abdillahi Yusuf resigning in early January 2009. Furthermore, Ethiopia has begun to withdraw its troops from Somalia, having made little progress towards stabilising the country. Peacekeepers from the African Union will fill some of the vacated positions to avoid a power vacuum. [6]

The long internal conflict in Somalia combined with natural disasters, such as water shortages and severe droughts, have left the country devastated. Hundreds of thousands of people have lost their lives and an estimated 2.5 million are in urgent need of assistance. Since January 2006 alone, an estimated 1.1 million people have been displaced in Somalia, with many seeking refuge in neighbouring countries. [7]

Given the local political instability, authorities in Somalia are unable to secure shipping in their waters. Indeed, local authorities, as far as they exist and function, often have more pressing issues to address. Furthermore, anti-piracy measures that have worked (at least to some extent) in other places that have relied on government forces of countries in which attacks take place, are also difficult to implement in the Gulf of Aden and off the Horn of Africa. In the Malacca Straits, for example, increased cooperation between the littoral states has reduced the number of pirate attacks. Given the current political situation in Somalia, such cooperation would be difficult – even if the necessary equipment was available to government forces.

International Responses

With local forces failing to secure Somali waters and the frequency and scale of pirate attacks posing a serious threat to global shipping, international concern grew, triggering two different kinds of responses. First, ship and cargo owners hired private security companies (PSCs) from different parts of the world to secure vessels transiting the pirate-infested waters. [8] Second, nations from around the world have sent warships to the area in addition to those international vessels already present. Warships from the US, Britain and other countries have been patrolling the waters off the Horn of Africa for the past eight years to combat terrorism. [9] The additional vessels were sent in recent months mostly from those countries whose ships have been targeted by pirates. Among the warships and personnel patrolling the area have been ships from the US, Canada, Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Malaysia and India. Many of these vessels are part of missions sanctioned or organised by multilateral organisations. Both NATO and the EU have, for example, been involved in combating piracy in the Gulf of Aden, with the NATO mission ending in December 2008, when EU efforts began. Both organisations have sent warships to patrol pirate infested waters, placing particular emphasis on the protection of UN aid vessels. [10]

This international presence has prevented a number of hijackings, with naval forces from a variety of countries having engaged in fire fights with pirates to foil attacks. British forces, for example, killed three pirates in a shootout in November 2008, while EU naval forces prevented an attack on a crude oil carrier on 2 January 2009. [11] France, which maintains a naval base in Djibouti, has also conducted successful operations against the pirates. In April 2008, French Special Forces arrested six pirates responsible for an attack on a French cruise yacht with 30 people onboard. After the hostages were released the pirates were captured in a daring helicopter attack on a jeep carrying the perpetrators and part of the ransom money in the semiautonomous province of Puntland. In September, French Special Forces recaptured a hijacked yacht 300 miles off Somalia. The pirates had taken the yacht and a French couple hostage, demanding a ransom of Euro 1 million and the release of the pirates earlier arrested by French authorities. Soldiers from the underwater combat unit successfully boarded the yacht at sea, shot one pirate and arrested the other six perpetrators. [12] Furthermore, every two weeks, the French Navy organises an escort for ships passing through the pirate infested waters. Merchant vessels in the area at the time can join the group free of charge. [13]

The latest country to join the international effort to combat piracy off Somalia is China. It is the Chinese Navy’s first operational deployment outside Asia, with the country sending two navy destroyers and a logistics ship to the pirate-infested waters in early January 2009. [14] International efforts were further boosted that month with the creation of Combined Task Force 151, which became fully operational in mid January. The task force was set-up by the US 5th Fleet, based in Bahrain, and concentrates on combating piracy in and around the Gulf of Aden, the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. It was established in addition to Combined Task Force 150, which focuses on other security operations in the area, such as anti-smuggling. Head of the new anti-piracy task force is US Rear Admiral Terence McKnight of the US Navy. More than 20 nations have been invited to join the task force, among them Australia. [15]

A Role for Australia?

Following the invitation to join the task-force Defence head Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston stated that the Department of Defence would consider deploying an Australian warship to the pirate infested waters off the Horn of Africa. Addressing sailors onboard the HMAS Parramatta in the Persian Gulf on 7 January 2009, he commented that different deployments of Australian warships are considered:

There is … the possibility of perhaps going further and getting involved in some of the important counter-piracy work that is coming on in the north Indian Ocean, (…) (We will be) looking at the options available and making recommendations to government on the best way to go. [16]

With Australia’s role in guarding Iraq’s offshore oil facilities coming to an end, a Defence spokeswoman confirmed that: “Defence is prepared for a range of contingencies, including the possibility of contributing to UN-sponsored anti-piracy operations off the Horn of Africa” but added: “No decision has been made and the deployment of Australian forces is a matter for government.” [17] Joining the debate, Defence Minister Joel Fitzgibbon voiced his concern about Somali piracy, but emphasised that he had not decided whether or not Australia should join the anti-piracy task force, despite the ADF’s capacity to “respond to a range of global contingencies”. [18]

The suggestion to send an Australian warship has already found support in some quarters. Teresa Hatch, executive director of the Australian Shipowners Association, for example, believes that Australia should contribute to the anti-piracy task force, pointing to the importance of the Gulf of Aden to international trade. [19] Anthony Bergin, Director of Research Programs for the Australian Strategic Policy Institute further stressed the importance of maritime trade for Australia, arguing that the protection of international shipping is of high strategic interest to Australia. [20] Indeed, the Gulf of Aden is of vital strategic importance, with more than 20,000 vessels travelling between Europe and the Middle East, Asia and Australia passing through the waterway every year. Among them are Australian merchant vessels, ships with Australian crew onboard, as well as vessels carrying cargo to and from Australia. [21] Australian cruise ships and those carrying Australian holidaymakers also sail through the Gulf of Aden and are targets for pirates. In fact, cruise ships from various countries have in the past months repeatedly come under attack, including those carrying Australian passengers. [22] Participation in the international anti-piracy efforts would therefore help protect Australian nationals and assets as well as national strategic interests.

Australia’s participation in the UN approved anti-piracy task force would also strengthen Australia’s role in international peacekeeping and security missions and support efforts by the international community – in the form of multilateral institutions – to address pressing security threats. For example, sending an Australian warship to Somalia as part of the UN approved mission would lend additional strength and resources to the international task force. This may not only help reduce the number of pirate attacks in this area, but also strengthen the UN’s role in addressing non-traditional security threats. Since the end of the Cold War, non-traditional security issues that in the past were not perceived as being part of the international security agenda have become increasingly important. Over the past two decades, it has also become more and more apparent that many non-traditional threats, such as terrorism, transnational crime or environmental degradation cannot be addressed by one state alone. In fact, the lines between national and international security have become blurred. In response, multi-lateral institutions, such as the UN or NATO, have become increasingly involved in addressing security threats, but have often encountered operational difficulties. Any support for UN approved missions, such as the deployment of a warship as part of the anti-piracy task force in Somalia, can contribute to the success of such operations and consequently strengthen the UN’s position as an institution capable of addressing and managing responses to international security threats.

Sending an Australian warship to support the anti-piracy mission would further confirm Australia’s willingness to be an international citizen as well as the Royal Australian Navy’s (RAN) capacity to respond to security threats around the world. While the Australian naval forces have been involved in numerous international assignments, (for instance, deployment to the Persian Gulf since the early 1990s) this would be an opportunity to participate not only in another high profile mission, but one that is in some respects remarkable. What sets this mission apart from prior operations is the participation of countries that have not previously deployed vessels far from their homeports. Most notably, this “is the first extended transcontinental naval operation deployment” [23] for India and China, demonstrating the new role and capabilities of these countries’ rising navies. It is also the first deployment of Western European vessels under an integrated EU command. [24]

Participation in this anti-piracy mission would therefore also offer the opportunity to work together with naval forces from these and a variety of other countries and strengthen Australia’s strategic international partnerships. Indeed, Bergin regards the possible deployment of an Australian warship as a chance to cooperate with other naval forces, particularly China, stating that:

Working with the [People’s Liberation Army] navy is very much in Australia’s interests (…) This can act as a confidence-building measure and build trust between other navies. It can generate understanding of other countries’ procedures and assist in overcoming cultural barriers to military co-operation. [25]

Cooperation with Chinese forces is of particular importance because the recent build up of naval strength in China has been viewed with interest – or even concern – in Australia. However, Bergin also warns that the rules of engagement of the Australian navy in the anti-piracy operation have to be clarified before a warship is deployed. Other observers have been more critical and have pointed out that the deployment of an additional warship will not solve the piracy problem. [26] In fact, there are many shortcomings and problems inherent in current international responses to piracy off the Horn of Africa.

Shortcomings and Problems of Responses

Despite some success stories, current international efforts are clearly not solving the piracy problem, with pirate attacks continuing to occur for a variety of reasons. There are, for example, problems and shortcomings in regard to the rules of engagement of international forces in the fight against Somali pirates. The role and involvement of the international navies is restricted by national and international laws. To facilitate the involvement of warships from outside Somalia, the UN Security Council adopted four resolutions in 2008. [27] In June 2008, for example, the Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1816 which:

Essentially, (…) authorizes countries to enter Somali territorial waters and use ‘all necessary means to identify, deter, prevent and repress acts of piracy and armed robbery’ by boarding, searching and seizing suspect vessels and arresting the perpetrators. The key conditions require states taking such action to cooperate with Somalia’s interim government and to notify the UN Secretary General. [28]

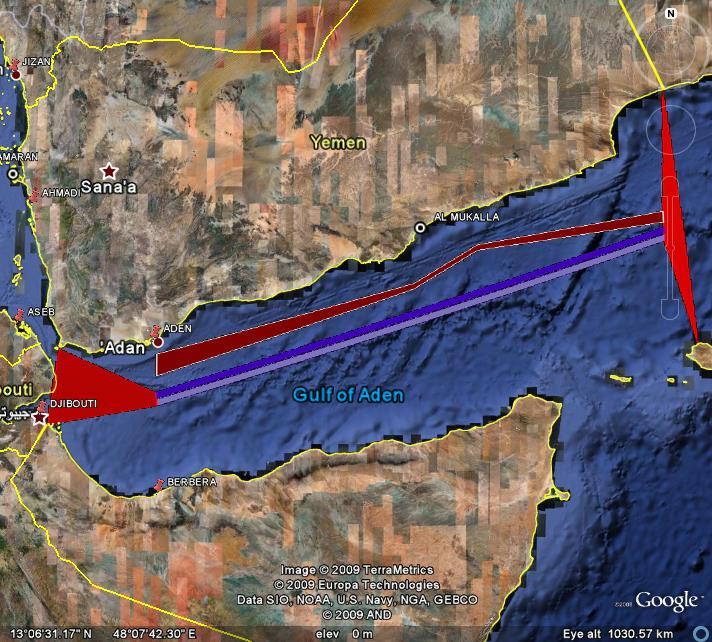

In accordance with this resolution, international warships are able to patrol the affected waters to prevent attacks, and have created a so-called Maritime Security Patrol Area, a safe corridor for ships to pass through the Gulf of Aden. [29] Yet, even within this zone the operations of international forces are restricted. [30] For example, as NATO spokesperson James Appathurai explained, NATO vessels were only allowed to patrol, deter and stop attacks but not to use force to recapture hijacked vessels or rescue crewmembers. [31]

To overcome some of these problems and to extent the authority of international forces involved in the anti-piracy operation, Resolution 1851 was passed by the Security Council in December 2008. It allows international forces with authorisation from the Somali government to pursue pirates on land until December 2009. While this resolution increases the capacity of international forces to act against pirates, operations on land are difficult to carry out, as has been demonstrated by earlier involvement of international forces in the country. One example is the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, in which two US helicopters were shot down and three others damaged while on a mission to capture members of a powerful clan. Hundreds of Somalis lost their lives in the operation which ultimately led to the withdrawal of US troops from the country. Today, the civil war continues, Somalia is awash with weapons, and the pirates have at least some local support. Locating and arresting pirates on land is consequently a difficult and dangerous task [32] that has the potential to exacerbate conflict in Somalia. As in earlier cases, operations by foreign forces in Somalia could result in the death of civilians and strengthen local antipathies towards foreign countries that have become involved in their homeland. In a worst-case scenario, such operations could intensify armed conflict and generate consequences, such as a further increase in crime or politically motivated violence that induce more foreign military responses.

Furthermore, the prosecution of pirates, caught on land or at sea, remains a problem. Jurisdiction is often unclear and pirates captured by international forces have been released in many cases because the arresting forces believed they could not convict the perpetrators under their respective national laws. As one commander describes: “It’s frustrating, (…) we catch them, confiscate their weapons, and then we let them go.” [33] Indeed, pirates can often only be brought to justice in a foreign country if the victims (the vessel or the sailors) are from the same country as the forces arresting the pirates. France, for example, brought pirates responsible for two attacks on French vessels to France for trial, while handing other arrested pirates over to Somali authorities. However, the Kenyan government has recently agreed to prosecute arrested sea-robbers, with Britain, for example, having handed captured pirates to Kenyan authorities to be tried. [34]

International responses also had operational deficiencies. Most worrying was the sinking of an alleged pirate mother ship by the Indian navy in November 2008. Unfortunately the ship was not a pirate vessel but a Thai fishing trawler that had been taken over by pirates earlier in the day. The trawler had a tracking device onboard and the owner of the vessel had notified the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) shortly after the hijacking. The IMB had broadcast the news to the coalition of navies involved in securing the waters off the Horn of Africa. While the British Navy confirmed the hijacking and backed away from the vessel, the Indian navy approached the ship later in the day, asking it to stop. A fire-fight between the two vessels ensued and the fishing trawler burned and sank. While two speedboats carrying pirates escaped from the vessel, only one of the 16 crewmembers of the fishing vessel was found alive – after drifting in the ocean for five days. [35]

Another shortcoming of the operation which further explains why piracy persists is that despite the increased number of international vessels and the establishment of the Maritime Security Patrol Area, the warships cannot cover the entire area in which pirates can operate. The attack on the Sirius Star , which took place hundreds of miles south of the Gulf of Aden, demonstrates that the pirates are flexible, and will attack in waters outside the area protected by foreign navies. Furthermore, even if allowed, recapturing hijacked vessels is not an easy task and such operations have so far only been successful when small vessels (predominantly yachts) were rescued. Operations to recapture merchant vessels, including tankers, are far more complicated. Indeed, not only has the life of the crew onboard to be considered but a failed attempt could damage the hijacked vessel, and could, for example, result in a major oil spill.

There are other reasons why the presence and operations of the warships have not brought an end to piracy. The most important reason, however, is that these efforts only address the symptoms and not the root causes of the problem. Piracy in this region is a direct result of the conflict, poverty and instability of Somalia. The pirates can only operate so successfully because they find supporters and willing recruits among the impoverished local population. As a36-year-old mother of five in Haradhere, close to where the super tanker was held, explains: “Regardless of how the money is coming in, legally or illegally, I can say it started a life in our town. (…) Our children are not worrying about food now, and they go to Islamic schools in the morning and play soccer in the afternoon. They are happy.” [36] Other factors such as illegal fishing and the ineffectiveness and corruption of government officials also play a role, with some observers suggesting links between Somali pirates and warlords. [37]

Conclusion: what is to be done?

Addressing and responding to piracy off Somalia is a difficult task. Indeed, piracy in these waters is likely to remain a problem until the political and humanitarian situation in Somalia improves. This is clearly a long-term project, requiring serious and sustained efforts by local leaders and the international community. However, given the scale of pirate attacks in this area, short term measures are also needed to prevent individual attacks, secure shipping and ensure that the situation at sea does not deteriorate further.

Australian naval deployments

The current effort by international naval forces is the most important of these short term measures to date. Despite shortcomings, international forces have been able to prevent numerous attacks and have demonstrated that pirates in Somalia (and other places around the world) cannot act with impunity. The deployment of an Australian warship would add further strength to this operation. As part of this multinational task force Australia would also support government-led, as opposed to private, responses to security threats. As discussed earlier, a second short-term measure to address piracy is the employment of PSCs. However, this can be problematic because these companies often operate in a legal grey-zone as rules and regulations regarding their activities are not clearly defined in places such as Somalia. [38] Government forces such as the Australian navy, on the other hand, are required to act according to UN set regulations and guidelines. Furthermore, a successful UN approved operation would also reinforce the institution’s role in addressing and managing responses to non-traditional security threats. Finally, the deployment of a warship to Somalia is also an opportunity to strengthen Australia’s profile in international security operations and to cooperate with naval forces from different countries.

However, there are still serious shortcomings with the current international responses. ‘Errors’ such as the sinking of the Thai trawler need to be avoided and information exchange between countries and institutions involved enhanced. Further improvements also have to be made in terms of the rules of engagement of international forces in Somalia and steps have to be taken to create (international) judicial mechanisms to bring arrested pirates to justice. A first step to address these issues was the formation of the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia. The first meeting of the group was held on 14 January this year at the United Nations, with Australia part of the meeting. [39]

Australian interventions for long term Somalian human security

While the creation of this group is a positive development, it is important to keep in mind that patrolling pirate infested waters will not address the underlying root causes of modern day piracy, which include illegal and over-fishing, lax (international) maritime regulations, ineffective and corrupt government forces, armed conflict and widespread poverty. [40] Addressing these root causes is not an easy task and combating piracy can consequently not be achieved by only those states in which pirate attacks actually occur. It is therefore important for Australia, and other countries already involved in combating Somali piracy, to understand that the current international patrols have to be seen as a first step in a longer process.

Indeed, without long-term measures that address the political and humanitarian situation in Somalia, the patrols of pirate-infested waters are of limited use because they will only foil individual attacks, and only within the area covered by patrol vessels. This will not discourage pirates from operating off Somalia as unprotected vessels still pass through the area and pirates can conduct attacks outside the waters patrolled by international warships. With these short-term measures not solving the problem, international warships will have to protect vessels passing through these pirate-infested waters for the foreseeable future – unless long-term measures are successfully implemented and supported. Countries such as Australia, Japan [41] and South Korea that consider sending warships to Somalia therefore have to understand that deploying warships could be a long-term commitment that may make little difference – particularly in regard to human security – if the political and humanitarian situation in Somalia is not addressed.

Consequently, the deployment of an Australian warship would make little sense unless Australia and other countries also take an active role in ensuring that long-term measures are taken and successfully implemented. For example, Australia could support efforts and policies that politically stabilise Somalia and bring an end to internal armed conflict. It is important in this regard to consider the interests of the Somali population and to support political solutions that are feasible as well as acceptable to the people of Somalia. In the past, international involvement in Somalia often had competing agendas, with some operations seeming to be driven predominantly by foreign rather than local interests. One example is the 2006 ousting of the Islamist government in Somalia by US backed Ethiopian forces. The US supported the campaign because it believed that the Islamists sheltered al-Qaeda operatives. The result was the end of a period of relative calm in Somalia during which there have been no serious pirate attacks. However, the resignation of the Somali President, who was seen by many as an obstacle to the peace process, and the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops from Somalia this January, may present another chance to relaunch the peace process. [42] Yet, stability can only be achieved in Somalia if room is found for the different Islamist factions and any alliance of local groups – including Islamists – can only be successful if their efforts are not undermined by foreign forces. As long as a new government does not oppress the local population, respects the internationally guaranteed rights of its people as well as the borders of neighbouring countries, international support should be given. [43] Indeed, foreign interests – such as eliminating hide-outs for terrorists – may best be served by supporting political solutions that will bring a government to power that has the ability to control and stabilise the country.

Australia could also back other efforts that aim at de-escalating the conflict in Somalia, strengthen the Djibouti peace process and enforce UN embargoes – such as the Somalia arms embargo. It could, for instance, support efforts to bring the violent US anti-terrorism campaign inside Somalia to an end. The campaign which is part of the broader war on terrorism has included airstrikes to kill suspected terrorists hiding in Somalia. However, the airstrikes have killed and wounded many civilians and have “weakened Washington’s credibility in the Horn of Africa and galvanised anti-American feeling among insurgents and the general populace, as well as undermined the international effort to mediate a peace process for Somalia.” [44] The Somalia Arms Embargo Monitoring Group has also declared that these airstrikes, as well as US training of Somaliland officers in Ethiopia without exemption from the Security Council committee, are a violation of the Somalia arms embargo. [45] While substantial changes in US foreign policy, including an end to airstrikes in Somalia, were unlikely under the Bush administration, there is hope that such changes may be possible now.

Furthermore, Australia could increase its support to address the grave humanitarian situation in Somalia. Short term, as well as long-term, assistance, administered through multilateral institutions such as the UN as well as NGOs, is needed to provide help to those affected by civil unrest and/or natural disasters. Finally, Australia could reinforce its efforts to combat other root causes of piracy, such as over and illegal fishing. In fact, support from countries such as Australia is needed to protect the marine environment and stop large fishing vessels, often operating under Flags of Conveniences (FOCs), from engaging in illegal fishing activities in waters throughout the world. In this regard, it is of particular importance to support initiatives of international bodies that seek to combat illegal and over fishing and attempt to address the shortcomings in the FOC system, including the International Maritime Organisation, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations and the International Transport Workers’ Federation.

While it is certainly a daunting task to successfully implement these long-term measures, they would hopefully lead not only to the eradication of piracy in Somalia, but also to more stability and security for the local population.

III. References

- ‘Pirates’ luxury lifestyles on lawless coast’, CNN, 19 November 2008, http://www.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/africa/11/19/somalia.pirates.boomtown.ap/index.html , accessed 20 November 2008.

- ‘ Piraten Ueberfaelle: Seeraeuber haben 17 Schiffe in ihrer Gewalt ‘, Spiegel TV , http://www.spiegel.de/video/video-41016.html, accessed 20 November 2008.

- ‘Pirate boat destroyed after new raid’, Australian, 20 November 2008. Llanesca T. Panti, ‘ Somali Pirates Release Philippine Ship and Crew ‘, Manila Times, 14 January 2009, http://www.manilatimes.net/national/2009/jan/14/yehey/metro/20090114met1.html, accessed 15 January 2009. Office of Naval Intelligence, ‘Worldwide Threat to Shipping Mariner Warning Information’, Civil Maritime Analysis Department, United States, 8 January 2009.

- Jason McLure, ‘ The Scourge of Somalia’s Seas ‘, Newsweek , 23 August 2008, http://www.newsweek.com/id/154930/output/print, accessed 26 August 2008.

- International Crisis Group, ‘ Conflict History: Somalia ‘, updated September 2008, http://www.crisisgroup.org/home/index.cfm?action=conflict_search&l=1&t=1&c_country=98, accessed 20 November 2008.

- Mohammed Ibrahim, ‘ Insurgents in Somalia Take Over Police Posts ‘, New York Times , 4 January 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/04/world/africa/04somalia.html?partner=rss&emc=rss, accessed 7 January 2009. ‘ Ethopia Begins Somalia Pullout ‘, BBC News, 2 January 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7808495.stm, accessed 18 January 2009.

- Ibid. Alex Perry, ‘ The Suffering of Somalia ‘, Time Online , 13 November 2008, http://www.time.com/printout/0,8816,1858874,00.html, accessed 20 November 2008. Daniela Kroslak and Andrew Stroehlein, ‘ Oh my Gosh, Pirates! ‘, International Herald Tribune , 28 April 2008, http://www.iht.com/bin/printfriendly.php?id=12399900, accessed 30 April 2008.

- Shipowners also tried to increase security by other measures such additional training for the crew and increased pirate watches.

- ‘Terror at Sea’, Times , 17 September 2008, p. 2.

- Petra Sorge, ‘ Alliierte gehen ohne Deutschland auf Piratenjagd ‘, Spiegel Online , 27 Oktober 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/0,1518,druck-584554,00.html, accessed 28 October 2008. North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, ‘ Somalia: Successful completion of NATO Mission Operation Allied Provider ‘ 12 December 2008, http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/JBRN-7M9K2N?OpenDocument, accessed 17 January 2009.

- Michael Evans, ‘ Royal Navy in Firefight with Somali Pirates ‘, Times Online , 12 November 2008, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/africa/article5141745.ece, accessed 18 January 2009. Office of Naval Intelligence, ‘Worldwide Threat to Shipping Mariner Warning Information’.

- Charles Bremner, ‘French Special Forces Seize Pirates in Operation to Free Yacht Hostages’, Times , 17 September 2008, pp.28-29. Bruce Crumley and Tony Karon, ‘ Will NATO Navies Stop Somali Pirates? ‘ Time , http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1853690,00.html?iid=fb_share, accessed 20 November 2008.

- Barbara Hans, ‘ Reeder ruesten gegen Piraten-Attacken ‘, Spiegel Online , 18 November 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/justiz/0,1518,druck-591243,00.html, accessed 29 January 2009.

- Philip C. Saunders, ‘ Uncharted Waters: The Chinese Navy Sails to Somalia ‘, PacNet, Nr 3, 14 January 2009, Center for Strategic and International Studies, http://www.csis.org/media/csis/pubs/pac0903.pdf, accessed 16 January 2009 [PDF, 28 Kb].

- American Forces Press Service, ‘ Multinational Task Force Targets Pirates ‘, US Department of Defense, 8 January 2009, http://www.defenselink.mil/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=52586, accessed 13 January 2009. Brian Wilson and James Kraska, ‘ Anti-Piracy Patrols Presage Rising Naval Powers ‘, YaleGlobal Online , 13 January 2009, http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/display.article?id=11808, accessed 16 January 2009.

- Quoted in: Sarah Smiles, ‘ Navy Plans Pirate Fight ‘, Age , 9 January 2009, http://www.theage.com.au/national/navy-plans-pirate-fight-20090108-7cw7.html, accessed 13 January 2009.

- Quoted in: Smiles, ‘Navy Plans Pirate Fight’.

- Quoted in: Ibid.

- Ibid

- Samantha Maiden, ‘ Australian Warship could be Sent to Indian Ocean in Piracy Purge ‘, Australian , 12 January 2009, http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,24902690-31477,00.html, accessed 13 January 2009.

- Smiles, ‘Navy Plans Pirate Fight’.

- ‘ Cruise Ship Passenger recount Ordeal of Attack ‘, SBS World News , 4 December 2008, http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/1001410/Cruise-ship-passenger-recount-pirate-ordeal, accessed 18 January 2009.

- Wilson and Kraska, ‘Anti-Piracy Patrols Presage Rising Naval Powers’.

- Ibid.

- Quoted in: Jonathan Pearlman, ‘ Australia to Take on Somali Pirates ‘, Sydney Morning Herald , 9 January 2009, http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/australia-to-take-on-somali-pirates/2009/01/08/1231004199160.html, accessed 13 January 2009.

- Maiden, ‘Australian Warship could be Sent to Indian Ocean in Piracy Purge’. American Forces Press Service, ‘Multinational Task Force Targets Pirates’. Carolin Liss, ‘ Privatising the Fight against Somali Pirates ‘, Working Paper 152 , Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, November 2008, http://wwwarc.murdoch.edu.au/wp/wp152.pdf, accessed 29 January 2009. [PDF, 202 Kb]

- Wilson and Kraska, ‘Anti-Piracy Patrols Presage Rising Naval Powers’.

- Jane Chan and Sam Bateman, ‘Security at Sea: Can Anything be done at the Somali Coast?’, RSIS Commentaries, 107/2008, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technical University, Singapore, 2008, p.1.

- Ibid.

- Bjoern Hengs and Katharina Peters, ‘ Verteidigungspolitiker fordern robustes Mandat fuer Marine ‘, Spiegel Online , 20 November 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/0,1518,druck-591484,00.html, accessed 20 November 2008.

- ‘Piraten Ueberfaelle: Seeraeuber haben 17 Schiffe in ihrer Gewalt’.

- December 2008. ‘ Uno erlaubt Piratenbekaempfung auch an Land ‘, Spiegel Online , 17 December 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/0,1518,druck-596888,00.html, accessed 17 December 2008.

- Paulo Prada and Alex Roth, ‘The Struggle to Bring Pirates to Justice – Piecemeal Nature of International Law Makes Prosecution Difficult; One Approach Circulates at United Nations’, Wall Street Journal (Asia), 15 December 2008. Wilson and Kraska, ‘Anti-Piracy Patrols Presage Rising Naval Powers’.

- Paulo Prada and Alex Roth, ‘The Struggle to Bring Pirates to Justice – Piecemeal Nature of International Law Makes Prosecution Difficult; One Approach Circulates at United Nations’. ‘ EU startet Anti-Piraten-Einsatz ‘ Spiegel Online, 8 December 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/0,1518,595212,00.html, accessed 9 December 2008. Bremner, ‘French Special Forces Seize Pirates in Operation to Free Yacht Hostages’. Crumley and Karon, ‘Will NATO Navies Stop Somali Pirates?’.

- Mark McDonald, ‘ Indian Navy Sank Thai Trawler, Not Pirate Ship, Owner Says ‘, International Herald Tribune , 26 November 2008, http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/11/26/asia/26PIRATE.php, accessed 17 January 2009. ‘ Indian Navy Defends Piracy Sinking ‘ BBC News , 26 November 2008, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7749486.stm, accessed 17 January 2009.

- ‘Pirates’ luxury lifestyles on lawless coast’.

- Crumley and Karon, ‘Will NATO Navies Stop Somali Pirates?’.

- Liss, ‘Privatising the Fight against Somali Pirates’.

- David Osler, ‘ Piracy Contact Group Launched ‘, Lloyd’s List , 15 January 2009, http://www.lloydslist.com/ll/news/piracy-contact-group-launched/20017608173.htm, accessed 18 January 2009.

- See: Carolin Liss, ‘ The Roots of Piracy in Southeast Asia ‘, Austral Policy Forum 07-18A, 22 October 2007. Carolin Liss, The Challenges of Piracy in Southeast Asia and the Role of Australia , Austral Policy Forum 07-19A, 25 October 2007.

- Following extensive discussions, Japan’s ruling coalition decided on 22 January 2009 to send naval-ships to Somalia to protect Japanese vessels and nationals. However, the government still has to decide what kind of vessels will be deployed. Jun Hongo, ‘MSDF Antipiracy Mission gets LDP Go-ahead’, Japan Times, 23 January 2009, htpp://search.japantimes.co.jp/print/nn20090123a3.html, accessed 21 January 2009. ‘ Japanese Taskforce Approves Naval Mission to Somalia ‘, Channel News Asia, 22 January 2009, http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/afp_asiapacific/view/404191/1/.html, accessed 23 January 2009. For a broader discussion of the deployment of the Japanese Maritime Self-Defence Force see: Richard Tanter, ‘ The Maritime Self-Defence Force Mission in the Indian Ocean: Afghanistan, NATO and Japan’s Political Impasse ‘, Japan Focus, 2 September 2008.

- McLure, ‘The Scourge of Somalia’s Seas’. Ethiopia Begins Pullout’.

- International Crisis Group, ‘Somalia: To Move Beyond the Failed State’, Africa Report No. 147, 23 December 2008, pp.i-ii.

- Ibid, p.26.

- Ibid.

- Thank you to Ken Adams of Smadanek for the excellent map of the Gulf of Aden Martime Security Patrol Area (sourced via EagleSpeak ). The image has been updated to show the change to the security patrol area. The routing has been shifted to the south and split into eastbound and westbound lanes.

IV. Nautilus invites your responses

The Northeast Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this essay. Please send responses to: napsnet-reply@nautilus.org . Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent.

Produced by The Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainable Development

Northeast Asia Peace and Security Project ( napsnet-reply@nautilus.org )

![]() The NAPSNet Policy Forum provides expert analysis of contemporary peace and security issues in Northeast Asia. As always, we invite your responses to this report and hope you will take the opportunity to participate in discussion of the analysis.

The NAPSNet Policy Forum provides expert analysis of contemporary peace and security issues in Northeast Asia. As always, we invite your responses to this report and hope you will take the opportunity to participate in discussion of the analysis.