v i r t u a l d i a s p o r a s

and global problem solving project papers

Information Technology, Virtual Chinese Diaspora and Transnational Public Sphere

Guobin Yang

Assistant Professor

Department of Sociology

University of Hawaii at Manoa

Guobin@hawaii.edu

Abstract:

This paper explores the implications of transnational public spheres for global civil society and world civic politics through an empirical analysis of virtual Chinese cultural sphere. Three components of the virtual Chinese cultural sphere are discussed: general websites, bulletin boards, and Internet magazines. The analysis shows that the virtual Chinese cultural sphere is a heterogeneous space characterized by diversity, segmentation and connection. It shapes state and inter-state behavior and exerts individual and societal influences in more or less tangible ways through three mechanisms: problem articulation, civic association and the mobilization of activism. Because of these functions, the virtual Chinese cultural sphere is itself an object of struggle. The paper concludes with several observations on transnational public sphere and world civic politics, noting especially the challenges facing this emerging realm of transnational public life. Policy implications and directions for future research are outlined.

Introduction

Recent work on global civil society (Smith, 1998; Warkentin and Mingst, 2000) and “world civic politics” (Wapner, 1995) has focused on the role of transnational NGOs and social movement organizations (TSMOs) in contemporary world affairs. Little attention has been paid to the less institutionalized and more episodic transnational discourse communities made possible by the combination of two conditions: new information technologies and diaspora population. This article takes a step in this direction by presenting an empirical analysis of online discourse communities in or related to cultural China. I will refer to these discourse communities as a “virtual Chinese cultural sphere.” The “inhabitants” of these virtual spaces may be called “virtual Chinese diaspora.” Being virtual, these inhabitants are hard to identify as individuals, but as groups, they are drawn mostly from the ethnic Chinese communities around the world, including new immigrants and students studying overseas. The transnational nature of the Internet also means that the diaspora population may access online spaces in its homeland, while people at home may enter online spaces hosted overseas by the diaspora. I will not attempt to clearly distinguish the “inhabitants” of the virtual spaces, but will concentrate on the spaces and the discourse in them.

I will argue that the virtual Chinese cultural spaces are a heterogeneous transnational public sphere characterized by diversity, segmentation and connection. This transnational sphere impinges on world civic politics in more or less tangible ways at multiple levels, individual, organizational, state, inter-state and societal. It does so through three mechanisms, by providing spaces where

1) both personal, local and global problems are articulated;

2) dispersed individuals and groups may interact and associate with one another and,

3) political activism may be mobilized. For these reasons, this transnational cultural sphere is hotly contested.

My analysis will proceed as follows. I start with a brief review of the scholarship on global civil society and world civic politics to situate my analysis in this theoretical literature. Second, I will map the contours of the emerging online Chinese cultural sphere and discuss some of its main features. Next, I examine the three mechanisms through which the virtual Chinese cultural sphere exerts influences in world affairs. Fourth, I show how this online sphere is a field of struggle. Finally, I discuss the implications of transnational public sphere for world civic politics. My empirical analysis is based mainly on my own ethnographic research over the past two years.

Global Civil Society, World Civic Politics and Transnational Public Sphere

Two themes dominate the literature on global civil society and world civil politics. First, scholars are concerned with the forms or components of global civil society. In this regard, most scholars consider global civil society as a realm of transnational associational life. Thus, Wapner speaks of global civil society as “that slice of associational life which exists above the individual and below the state, but also across national boundaries” (1995: 313). Lipschutz (1996: 51) emphasizes organizations or alliances that operate at the international level or national groups and organizations that are in touch with their counterparts elsewhere in the world, an emphasis shared by Warkentin and Mingst (2000). Even scholars of transnational social movements emphasize the organizational aspect of the movements, despite some degree of fluidity characterizing these movements. Hence the new coinage TSMOs (transnationals social movement organizations) (Smith, Chatfield and Pagnucco, 1997; Alger, 1997). Related to this concern with transnational social organizations is a second theme in the literature on global civil society. As Wapner (1995) argues, much of the attention is directed at showing how international NGOs (INGOs) influence state and inter-state behavior. Wapner himself cautions against such a narrow focus and stresses the societal influences of transnational environmental activist groups (TEAGs). His empirical analysis illustrates how TEAGs disseminate an ecological sensibility, influence corporate politics and empower local communities, “above the individual and below the state, but also across national boundaries” (1995: 313).

This brief review offers two lessons for my study. First, following Wapner, I suggest that studies of global civil society need to look beyond state and inter-state behavior at the societal influences of transnational actors. I will go further and maintain that instead of just focusing on the effects of world civic politics, it is also important to understand the conditions of its emergence and its internal dynamics. A focus on transnational public spheres provides a unique angle to look at these dynamics and conditions. Second, while it is crucial to understand the role of INGOs and TSMOs in world politics, there are other dynamics and forces that need to be examined. For example, studies of INGOs and TSMOs often lack a conception of cultural and non-material factors such as discourse and identity, which are equally crucial to the processes of world politics. Furthermore, researchers should not underestimate the unorganized, spontaneous and fluid sources of collective action, which have proved vital in national social movements such as the 1989 pro-democracy movement in China (Calhoun 1994). To a great extent, contemporary social movements are characterized by fluidity (Melucci, 1989). Analyzing transnational public spheres may help to foreground these neglected issues.

Following Guidry, Kennedy and Zald (2000: 6), I consider transnational public sphere as “a space in which both residents of distinct places (states or localities) and members of transnational entities (organizations or firms) elaborate discourse and practices whose consumption moves beyond national boundaries.” An online public sphere differs from this conception in that its publics are less visible and less bound to physical locations and thus more deterritorialized.

Mapping the Virtual Chinese Cultural Sphere

Online spaces are a moving target and hard to map. As Appadurai (1994: 3) says of electronic media, these spaces “offer new resources and new disciplines for the construction of imagined selves and imagined worlds.” To understand them requires the work of imagination. What I present below should be taken as materials for the work of the imagination, not as the entire terrain of the virtual Chinese cultural sphere. I will focus on three components of this virtual sphere: general websites and portal sites, bulletin board systems (BBS) and Internet magazines.

Chinese-language Websites

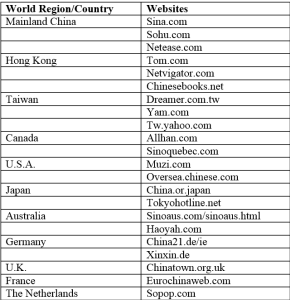

Cwrank.com is a North American Internet company specializing in ranking popular Chinese-language websites world-wide. Its listings provide an overview of the popular Chinese-language websites. For example, it maintains a listing of 60 popular websites in mainland China, 60 in Taiwan and Hong Kong and 60 in other regions of the world (http://www.cwrank.com). Besides specialized websites such as online magazines and bookstores, these include the most popular portal sites, such as sina.com in mainland China, yam.com in Taiwan, tom.com in Hong Kong, and muzi.com in the U.S. Many of these websites are commercial, but increasingly commercial sites are combining entertainment with business. Portal sites thus commonly have bulletin board systems (BBSs), chatrooms, virtual communities, online magazines, as well as news, sports, music, financial information, etc. Table 1 lists a sample of popular Chinese-language websites by world region.

Table 1 Twenty Popular Chinese-Language Websites by World Region

March 31, 2002*

*Compiled based on sources in www.cwrank.com

Bulletin Boards Systems (BBSs)

Several websites maintain listings of popular Chinese-language BBSs, including topforum.com, geocities.com and cwrank.com. To my knowledge, at least two websites, topforum.com and cat898.com, specialize in publishing a daily selection of popular postings from different BBSs. For example, topforum.com publishes 300 postings daily selected from 1,225 BBSs as of April 13, 2002. These BBS listings and content organizers greatly facilitate readers interested in exploring the online world of Chinese-language BBSs. There is evidence that users within China often access BBSs located outside of China.[1]

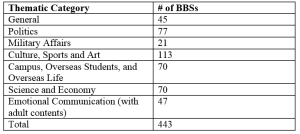

BBSs are usually organized by topic. For example, as of April 13, 2002, Geocities.com classifies its BBS listing under seven broad thematic categories. Table 2 shows the number of BBSs in each category.

Table 2 Listing of Chinese-language BBSs by Thematic Category,

Geocities.com, April 13, 2002

Source: http://www.geocities.com/Paris/Lights/4323/top20.html.

Discussions in these forums range far and wide. For example, a long message was posted to the US-based forum lundian.com on April 9, 2002 challenging proponents of a multi-party political system in China to respond. It begins with the following remarks:

Here are the realistic and most important conditions facing today’s China: vast

land, numerous ethnic groups, huge population, underdeveloped economy. Such

a country can only be governed at this point through centralized power…. So far no other country with these four conditions present simultaneously has been able to institute a multi-party system.[2]

These discussions are interesting not because they will lead to any real political solutions in the foreseeable future, but because they are taking place at all. It is hard to tell for certain who participate in these discussions. Judging from the fact that the discussions take place in online forums located in different parts of the world and that discussants sometimes reveal their physical locations explicitly or implicitly, it is clear that the participants are drawn from a transnational audience both in and outside of China. This transnational character is significant in two ways. It enables interested persons outside of China, the virtual Chinese diaspora, to be engaged in political discussions about China. It also enables those in China to voice their opinions on issues that are not yet on the public agenda in China’s domestic public sphere. This is a unique advantage offered by the virtual Chinese cultural sphere.

Internet Magazines

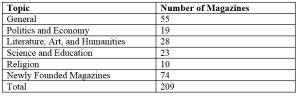

Similar to BBSs, Internet magazines specialize in different topics, literary, political, academic, religious and others.They are run from and distributed to many regions of the world. Cathay.net has a list of 209 Chinese-language Internet magazines as of March 18, 2001. Table 3 shows their distribution by topic.

Table 3 Distribution of 209 Online Chinese-Language Magazines by Topic,

March 18, 2001

Source: http://www.cathay.net. Retrieved July 3, 2001.

Internet magazines that report current affairs of world regions or publish creative or critical writings are especially popular. One of the most popular Internet magazines with a focus on current affairs is probably China News Digest(www.cnd.org). It was set up on March 6, 1989 by four Chinese students in Canada and the United States as an English-language newsletter for Chinese students in the two countries. Over the years, it has developed into an Internet news network with a global edition as well as special editions covering Canada, China, the United States and Europe/Pacific.It has also added such new features as a well-known Chinese-language magazine Hua Xia Wen Zhai, online communities, discussion forums, and virtual museums on the Cultural Revolution and the 1989 pro-democracy movement in China.

Internet magazines devoted to creative and critical writings fall into two categories. One category is mainly literary, though it often contains works on other topics. The other may be called intellectual magazines (xueshu wangzhan).These usually feature writings of a more academic nature. The topics in intellectual magazines range as widely as those covered in the bulletin boards, though some have clear political orientations. For example, “China Austrian Review” (sinoliberal.com) showcases works by China’s liberal scholars, while “Voices from the End of the World” (Tian Ya Zhi Sheng, tianya.com.cn/cgi-bin/default.asp) is a neo-leftist magazine with both print and electronic versions.

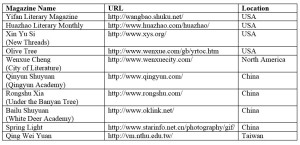

Internet magazines apparently have a large readership spanning various world regions. For example, CND’s most recent statistics show that by 1999, it had about 50,000 subscribers in 111 different countries or regions of the world. From May 14, 1998 to March 17, 2002, the Taiwan-based literary website Qing Wei Yuan (http://vm.nthu.edu.tw) had close to four million visitors, with more than 17 million hits.[3] Table 4 lists a sample of the most popular literary magazines.Table 5 shows a list of intellectual magazines.

Table 4 Selected Chinese-language Literary Magazines in World Regions,

March 2002

Table 5 Selected Online Intellectual Magazines in China,

March 2002

Characteristics of the Virtual Chinese Cultural Sphere

These virtual Chinese cultural spaces have three characteristics: they are diverse, segmented, and yet connected.

Diversity

The emerging virtual Chinese cultural sphere consists of diverse spaces. I have discussed a sample of portal sites, BBSs and Internet magazines, but there are also numerous newsgroups, chatrooms, electronic newsletters, etc. This kind of diversity is a general feature of the Internet, not unique to online Chinese cultural spaces. Second, virtual Chinese spaces are diverse in content. A look at any popular portal site will give some idea of the contents. Again, such diversity is not necessarily unique to Chinese cultural spaces. Thirdly, virtual Chinese spaces are diverse in how they are used. They are used both as a source of information and a medium of communication and expression. In this particular area, virtual Chinese spaces have acquired some unique features. For example, bulletin boards and Internet magazines enjoy special popularity among Chinese-language users. This is so in spite of the fact that Chinese characters are harder to input than the English alphabet. It is the case both in Taiwan and mainland China.

The diversity of these virtual spaces suggests some degree of pluralism. It is pluralism in the weak sense, however. In its strong sense, pluralism refers not just to the existence of diversity, but the democratic value of mutual respect among differences and the celebration of differences. In reality, the existence of pluralism in its weak sense often passes for pluralism in its more democratic sense. To avoid such misunderstanding, I would like to emphasize here that while virtual Chinese cultural spaces are diverse, they also demonstrate a high degree of segmentation, and to some extent, even fragmentation.

Segmentation

First, virtual spaces are segmented in issues and topics. The virtual communities supported by portal sites such as sohu.com are classified according to areas of interest. So are bulletin boards, newsgroups and listservs. In one sense, the segmentation of online spaces according to issues merely reflects the general trend of life-world differentiation in modern society: social life becomes increasingly compartmentalized based on occupations and personal needs. The segmentation of issues and topics, however, does matter for understanding the nature of online publics.

Online publics are also segmented, because each particular space tends to draw its own public. One reason for this is the sheer number of spaces available online. Users have limited time and energy and therefore tend to settle down to a few spaces. What people choose to inhabit what space is harder to say. There is no doubt about some correlation between the locations of the online spaces and those of the users. Thus, the publics of a university BBS are more likely to be its own students. But it is also clear that publics tend to form around special issues and topics, such as politics, literature and movies.

One consequence of the segmentation of online spaces is the creation of multiple and partial publics. When Habermas analyzes the public sphere in early modern Europe, he assumes the presence of a unitary public and consensual public opinion flowing from the rational-critical debate among its members. As noted by his critics, this is an idealized picture in the first place, because Habermas neglects those publics existing outside of the bourgeois public sphere. In today’s world of the mass media, it is still possible to imagine relatively homogeneous publics, or at least publics exposed to homogenizing media. In China, for example, this is true of the publics of the People’s Daily newspaper and the CCTV channels. In the United States, mass media publics form around a finite number of television networkssuch as CNN .Homogenous publics are hard to imagine in online spaces. It may be argued that on the Internet, there are as many publics as spaces.

Connection

The diverse and segmented spaces are potentially, and in many cases actually, connected, often in ways that transcend territorial boundaries. The connections among these spaces mark a distinct new development in the history of the media.These connections have a technological basis, but technology in itself is an insufficient condition for creating social connections. To understand these connections, it is necessary to raise sociological questions.

One question to ask is about the common practices in the use of the Internet. Several common practices directly contribute to the connections among virtual spaces. In bulletin boards, for example, cross-posting of messages is a common practice. Often, a particularly revealing or well-written message will be cross-posted to many bulletin boards.At other times, users of one bulletin board will be lured by these messages to surf other bulletin boards. These practices establish ties among different virtual spaces.

Brand names have a cohesive effect. As in the conventional media, on the Internet, some websites are more popular than others. Users of several different and little known bulletin boards may be sharing one same well-known BBS. Among web users, lack of knowledge of some popular sites may be taken as a sign of ignorance.

Thirdly, external conditions contribute to the connection of virtual spaces. One such condition is population dispersal.Both the existence of diaspora communities and the emergence of transnational business, scholarly and scientific communities provide the social conditions for online connections. An obvious example is the heavy use of the Internet among Chinese students studying overseas. Several of the websites created by these small groups of people in different parts of the world, such as cnd.org and muzi.com, have become brand names among the virtual Chinese diaspora. Their success story is a story of connection: they provide points of entry and connection for a dispersed population.

Virtual Chinese Cultural Sphere and Mechanisms of Political Influence

The diverse, segmented and yet connected features of virtual Chinese cultural sphere have implications for how the virtual sphere may exert real political influences. Diversity is a measure of openness, pluralism and democratic participation. Segmentation limits the effectiveness of democratic participation and reduces the chance of forming politically influential public opinion. Connection strikes a balance between diversity and segmentation by providing a mechanism for linking segmented publics and discourses into pluralistic discourse communities. Together, these three features present an image of a heterogeneous public sphere. To the extent that a democratic public sphere encourages openness and multiple views and recognizes conflicts (Fraser, 1992; Brown, 1994; Calhoun, forthcoming), the emerging virtual Chinese cultural sphere is more consistent with than against democratic principles. This transnational public sphere bears on world civic politics in three ways. It is a space for articulating personal, local and problems, for dispersed individuals and organizations to link up, and for mobilization and activism.

Problem Articulation

In The Reinvention of Politics, Ulrich Beck (1997) articulates the rise of subpolitics in contemporary society. In subpolitics, agents outside the political or corporatist system appear on the stage of social design. Thus, for example, it is the citizen initiative groups that have put the issue of the endangered world on the political agenda. Moreover, in subpolitics, not only collective agents, but individuals as well strive to shape politics. Having been banished (by sociologists) for a long period of time, the individual has now returned to society with a vengeance. This is nowhere more salient than in online Chinese cultural spaces. The subpolitics in virtual Chinese cultural spaces takes many forms, but the most important form is the articulation of social problems. Examples are numerous. On any random day, a visit to such popular online forums as topforum.com or www.cat898.com will bring discoveries about new social issues. On April 4, 2002, for example, a message entitled “Confronting Urban Poverty” attracts my attention. It makes the argument that while rural poverty remains a challenge, China now faces another challenge, urban poverty. This is a global issue, the author further argues, as can be seen from the theme of “World Habitat Day 2001: Cities Without Slums.” The question it leaves lingering is: Will Chinese cities become future cities with slums?

While most problems are articulated in an episodic manner, sometimes persistent efforts are made to publicize social problems. A report in the influential American magazine Science describes how a Chinese biochemist uses the Internet to expose corruption in the Chinese academia (Xiong, 2001). In 1994, Shi-min Fang, pen-named Fang Zhouzi, a biochemist based in California, set up a website called New Threads (www.xys.com). Among other things, Fang uses the site to publish essays and reports about plagiarism and other kinds of corrupt and unethical practices among some natural and social scientists in China. Over the years, these online publications have influenced China’s academic communities in various ways. In one case, the Chinese Association of Biochemists issued a policy prohibiting its members to appear in commercial advertisements in the name of the Association (Fang, 2001).

The articulation of personal and social problems means that new issues may be brought onto the public agenda through the Internet. Academic corruption is just one issue. There are many others, such as bureaucratic corruption, immorality, poverty and other new forms of social inequality, environmental degradation and educational problems. The wide-spread concern with these issues suggests that to some extent they resemble what Dieter Rucht (2000) refers to as “distant issue movements,” those cases of popular mobilization around issues that are not necessarily related to the situation of the mobilizing group.

Civic Association

Public sphere provides a space for associational and participatory activities. This is no less true of virtual public spaces.These activities may or may not be transnational or directly political, but they may serve such functions when the occasion arises. Two kinds of associational activities may be distinguished. First, some online spaces, such as chatrooms, bulletin boards and online magazines, attract participants. Much like the reading publics that form around a newspaper or a magazine, online publics form in these spaces. Second, existing social groups may use the online space for organizational purposes. In social science literature, much attention has been devoted to first type of associations.Studies of virtual communities (Rheingold, 1993) and social networks (Wellman, 1997; Mele, 1999) fall in this category.

In the emerging virtual Chinese cultural sphere, both types merit attention. For example, cnd.org offers a community homepage that includes online forums, alumni associations, matchmaking services, job information, and a directory of Chinese Students and Scholars Associations (CSSA) across the world. This community homepage functions as a portal to various online associational activities among Chinese diaspora in various parts of the world.Cn.geocities.com/zqscusa is an example of the second type of associational activities. It is the website of an existing organization called Zhi-Qing Association of Southern California. This organization was set up in 1998 and then registered as a nonprofit organization in 2001 by a group of former zhiqing (educated youth) who now live in Southern California.[4] Besides publishing announcements of activities, their website also runs a bulletin board, which sometimes attracts visitors from inside China. Indeed, members of this California-based organization are involved in virtual interactions with former zhiqing in China. For some time they even provided free web server service for a zhiqingwebsite based in China when that website was eliminated by Chinese authorities.

Mobilization and Activism

How may the virtual Chinese cultural sphere be directly linked to political action?

This question is not often asked about public sphere, but it is important enough to merit discussion. The virtual Chinese cultural sphere impinges on political action by facilitating and producing various forms of collective action. First, it is a space into which local forms of activism may enter and thus become transnational. The reverse is also true: transnational social movements may enter this space to influence local issues. Because of the transnational character of the Internet, the two processes are not often distinguishable. A good example of a transnational social movement on the Internet is the Falun Gong movement. Still hotly debated as to its nature and political implications, the Falun Gong movement first came to the world’s attention in April 1999 when about 10,000 of its members held a sit-in in Beijing. In July that year, the Chinese government declared Falun Gong organizations illegal and launched an aggressive offensive against these groups. Thereafter, the movement went underground and onto the Internet. Many observers have commented on the savvy use of the Internet by the movement, though systematic studies are scarce (for two useful sociological treatments, see Madsen, 2000 and Lin). I visited the organization’s “official website” on April 12, 2002 and found a listing of websites of the organization’s branches in 35 different countries or regions of the world.

While existing movements may migrate online, the virtual Chinese cultural sphere has also been used to mobilize new movements, both locally and globally. I have discussed several well-known events elsewhere (Yang, forthcoming). It is worth emphasizing that while in traditional studies of public sphere the political functions of public sphere are state-centered, in a transnational public sphere, it takes on influences at the global level while retaining its functions within the nation-state. The impact of a Chinese-language public sphere should be viewed in the same perspective.

Virtual Chinese Cultural Sphere as a Field of Struggle

Because of these possible uses of the transnational Chinese cultural sphere, this virtual sphere has become a field of struggle. Chinese government authorities attempt to influence this public sphere by maintaining their own online presence. Thus major newspapers in China now all have online versions. Authorities also attempt to influence this virtual sphere by controlling access. Some influential Chinese-language websites run outside of China, such as cnd.org, muzi.com, creaders.org, cannot be easily accessed from within China because of blocking. Operators of these websites, on the their part, do not give up their attempts to reach China’s domestic audience. Both cnd.org and muzi.com publicize proxy servers on their websites to help users to circumvent Internet blocking. For instance, cnd.org addresses its readers with the following:

Can you help CND to reach more readers by setting up proxies? How about e-mailing the list of proxy servers to your friends who might have trouble accessing this site? Thanks! (www.cnd.org, accessed July 12, 2002).

The virtual Chinese cultural sphere is not only a field of struggle between authorities and web operators, but also among web users themselves. China watchers are now familiar with the online forum “Strengthening the Nation Forum” (Qiangguo luntan, http://202.99.23.237/cgi-bbs/ChangeBrd?to=14) hosted by China’s government newspaper People’s Daily. One of the best-known online Chinese-language forums, “Strengthening the Nation Forum” has been a space for endless debates about online freedom of speech. There are personal attacks and other kinds of irrational behavior here.Critics would make arguments like the following:

Some net friends (wangyou),[5] for lack of a rational attitude to their own and other users’ view points, would become angry when they are stuck in their arguments. They cannot control their anger, thus resulting in personal attacks and slandering. These net friends have a superficial knowledge of the world. They thought they could shut others up with personal attacks. In fact, as soon as you launch a personal attack, you discredit both your own view points and your character (Haohao, February 1, 2000).[6]

For analysts of public sphere and civil society, there is nothing surprising about the internal struggles and external constraints affecting the virtual Chinese cultural sphere. The thrust of Habermas’s analysis of the structural transformation of public sphere is to show how political power and economic interests penetrated and weakened public sphere in 20th-century Western democracies. What is notable about struggles over online public spaces is the fact that despite external limiting factors and internal problems, individual and groups still enjoy some degree of leverage and freedom in entering these spaces. Nothing is predetermined, even in a government-run forum, and the shape of the public sphere depends on the results of the struggles among the actors involved. This is a key point to remember not just about the virtual Chinese sphere discussed here, but about transnational public spheres in general. It is a point fully recognized by the authors of some recent works on transnational public sphere. As Guidry, Kennedy and Zald argue (2000:9), “Public spheres, whether transnational or national, are thus characterized by a measure of contest and contingency that is difficult to recognize…. They are volatile and do not preclude the possibility of violence.” By violence, the authors refer to such uncivil and undemocratic practices as are sometimes found in online forums. The existence of such practices discourages a view of public sphere as inherently democratic and invites a more complex understanding that these public spaces are contested spaces beset by tensions and contradictions.

Conclusion: Transnational Public Sphere and World Politics

The virtual Chinese cultural sphere described here is an example of transnational public sphere. As such, it typifies features of other types of transnational public spheres. It provides the starting point for four general observations on transnational public sphere and world politics. First, transnational public spheres are emerging as a new force in global civil society and world civic politics. They are made possible by the conjunction of several conditions: the dispersal of populations, the disembedding of personal identities (Giddens, 1991), the development of new communication technologies, the growing influence of non-governmental organizations, and above all the increasing awareness of the common risk conditions faced by the world population (Beck, 1992, 2000).

Second, the emerging transnational public spheres may exert more or less tangible influences at multiple levels, individual, organizational, state, inter-state and societal. This happens through three mechanisms: problem articulation, civic association and the mobilization of activism. Here individuals have gained a new capacity to influence national and international affairs. Dispersed persons and groups may form episodic and temporary alliances through the mediation of transnational public spheres. A virtual diaspora may produce real political effects without being constrained by disciplinary, territorial-bound state regimes.

Third, while transnational public spheres may have direct and immediate influences in world affairs through mobilization and activism, it is probably the long-term, less tangible effects that will prove to be most significant. These effects pertain to two areas: value orientation and social integration. Will transnational public spheres contribute to the clarification and cultivation of cosmopolitan democratic values? How? Will they contribute to world peace by enhancing social integration and reducing physical violence? My study of the virtual Chinese cultural sphere does not provide answers to these questions but highlights some areas in which to look for answers in the future. Value orientation in a cosmopolitan world should be developed through dialogue involving the participation of ordinary citizens. The Internet offers spaces for such dialogues. Thus, it is important to look to the development of online public spaces for an understanding of the processes and contents of cosmopolitan value construction. This is not to neglect other important, more institutionalized areas. The emphasis here is on citizen participation.

Global social integration is a harder question to tackle. It may be politically problematic if it is understood as the global integration of local societies. By social integration, I mean whether or not transnational public spheres will contribute to the building of collective solidarities and what kinds of solidarities will emerge out of these processes. If they are parochial solidarities among small groups, who bind together to advance private interests instead of social justice and equity, then these solidary groups do not contribute to global civil society or world civic politics. By the same token, large collectivities that join efforts only to advance group interests without heed to social justice and equity do not contribute to cosmopolitan democratic principles either. At this moment at least, transnational public spheres like the one studied here do not show any tendency to yield either type of solidarities, for better or worse. What emerges out of the virtual Chinese cultural sphere are discourse communities. People, or rather their words and voices, come and go, forming at most episodic, temporary communities. They occur in response to specific issues and dissolve quickly. With the change of issues, members of such episodic communities may change memberships or even find themselves in opposition on a different issue. Episodic communities therefore are temporary, strategic alliances. They cannot be institutionalized and do not have clear, predictable patterns.

More permanent and stable groups do exist on the Internet, but they tend to have a “real” basis. They have either been formed before going online, or after forming online groups, members begin to consolidate their relationships by having offline interactions. In the first case, the Internet plays a secondary role in solidarity building. In the second case, the Internet plays a primary role initially but then recedes somewhat with the simultaneous rise of offline interactions. In short, transnational public spheres have a limited role in building “thick” solidarities.

The fourth and final observation about transnational public spheres is that they are an incipient but dynamic phenomenon. They are not well-developed and not institutionalized. Though connected internally and with external forces, they lack coherence and are beset with tensions, contradictions and problems. These problems arise both internally and externally. They constitute challenges and hopes for the future development of transnational public spheres. External obstacles are economic and political in nature. They include the problems of equal access, political control and surveillance and commercialization. These are the classical problems analyzed by Habermas, but they remain central to understanding the present and future of transnational public spheres. The development of democratic transnational public spheres, however, does face new challenges. One of these is control through computer architecture exercised by the invisible—and global–hand of the market (Lessig, 1999). A case that attracted much public attention in this regard is the role the Canadian company Nortel Networks plays in helping to build China’s Internet firewall (Walton, 2001).

Internal challenges include the problems of equal voice, reflective dialogue (Kurland and Egan, 1996) and civic discourse. Participants in online forums want their voices to be heard, but online interactions are as fraught with inequalities as face-to-face interactions. Furthermore, online discourse may be uncivil, thus obstructing the free flow of rational debate. Uncivil discourse may simply reflect some participants’ inability or unwillingness to engage in equal and rational dialogue. Sometimes, however, it emanates from conflicts based on a sense of imagined collective identity or hostility, an imagination fanned by the words and images circulating online. The world witnessed an outburst of uncivil and even hateful discourse in 2001 during the period of the American spy plane incident in the South China Sea.Often reflecting primordial sentiments of nationalism (Kluver, 2001), the discourse poured into Chinese and American online forums alike. Careful observers may notice the tendency for the discourse to move from the less reasoned to the more reasoned in the process of online interactions, indicating that online public sphere is capable of developing communicative reason. Yet the initial outburst of uncivil discourse could be considered as an instance of the temporary collapse of online public spheres. This collapse betrays the fragility of these spaces and sounds a cautionary note to observers.

These observations contain policy implications as well as directions for future research. First, if public sphere is of any use in traditional democratic politics, it is time to put the construction of transnational public spheres on the agenda of global politics. State and non-state policy makers as well as researchers will need to understand better 1) the forms and dynamics of transnational public spheres that are emerging; 2) the different roles that different actors play in the process; 3) the issues that enter the transnational public sphere; 4) the channels through which issues are brought into and out of transnational public spheres; and 5) the connections and interactions between transnational and national public spheres.

Second, the heterogeneous character of transnational public spheres should be considered as a strength, not a weakness.Thus, any efforts to build an institutionalized or homogeneous transnational public sphere will be misplaced.Transnational public spheres are global but also decentralized. The energy of transnational public spheres derives from their diversity and even tensions and conflicts. Given the heterogeneous character of transnational public spheres, the challenge is three-fold: to overcome internal obstacles to the democratic functioning of these spaces, to prevent these spaces from being dominated by any form of political or economic power, and to channel the critical issues articulated in these spaces into the broader public. There is no doubt that government and non-governmental organizations have a unique role in shaping the outcomes. Yet the outcomes also depend crucially on the continual functioning of the emerging transnational public spheres, which in turn depends on the participation of citizens and citizen groups. It is the dialectics of voluntary participation and strategic action on the part of all actors that will shape the future of transnational public spheres and their role in world civic politics and global civil society.

Bibliography

Alger, Chadwick F. 1997. “Transnational Social Movements, World Politics, and

Global Governance.” Pp. 260-275 in Transnational Social Movements and

Global Politics: Solidarity Beyond the State, edited by Jackie Smith, Charles

Chatfield and Ron Pagnucco. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization.

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Toward a New Modernity. London: Sage

Publications.

Beck, Ulrich. 1997. The Reinvention of Politics. London: Blackwell Publishers.

Beck, Ulrich. 2000. “The Cosmopolitan Perspective: Sociology of the Second Age of

Modernity.” British Journal of Sociology 51: 79-105.

Brown, Elsa Barkley. 1994. “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African

American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom.” Public Culture 7(1): 107-46.

Calhoun, Craig. 1994. Neither Gods Nor Emperors: Students and the Struggle for

Democracy in China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Calhoun, Craig. .Forthcoming. “Constitutional Patriotism and the Public Sphere:

Interests, Identity, and Solidarity in the Integration of Europe,” in Pablo de Greiff

and Ciaran Cronin (eds), Transnational Politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

CNNIC. January 2002. “Report on China’s Internet Development: January 2002.”

Http://www.cnnic.net.cn/develst/cnnic200201.html.

Fang, Zhouzi. 2001. “In the Name of ‘Science’ and ‘Patriotism’: Academic Corruption

in China.” Speech delivered at UCSD on November 18, 2001. http://www.xys.org/xys/netters/Fang-Zhouzi/science/yanjiang.txt.

Retrieved April 12, 2002.

Fraser, Nancy. 1992. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of

Actually Existing Democracy.” Pp. 109-142 in Habermas and the Public Sphere, edited by Craig Calhoun.Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Guidry, John A., Michael D. Kennedy and Mayer N. Zald. 2000. “Globalizations and Social Movements.” Pp. 1-34 inGlobalizations and Social Movements: Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere, edited by John A. Guidry, Michael D. Kennedy and Mayer N. Zald. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Habermas, Jurgen. 1989. The Structural Transformation of Public Sphere. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Habermas, Jurgen. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Kluver, Randy. 2001. “New Media and the End of Nationalism: China and the US in a

War of Words.” Mots Pluriels, 18, August. http://www.arts.uwa.edu.au/MotsPluriels/MP1801ak.html.

Kurland, Nancy B. and Terri D. Egan. 1996. “Engendering Democratic Participation via the Net: Access, Voice and Dialogue.” The Information Society 12: 387-406.

Lawrence Lessig. 1999. Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace. New York: Basic Books

Lin, Nan. 2001. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lipschutz, Ronnie D, with Judith Mayer. 1996. Global Civil Society & Global Environmental Governance. Albany: SUNY Press.

Madsen, Richard, “Understanding Falun Gong,” Current History 99 (2000): 243-247.

Mele, Christopher. 1999. “Cyberspace and Disadvantaged Communities: The Internet as a Tool for Collective Action.”Pp. 290-310 in Communities in Cyberspace, edited by Marc A. Smith and Peter Kollock. London: Routledge.

Melucci, Alberto. 1989. Nomads of the Present: Social Movements and Individual Needs in Contemporary Society.Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Rheingold, Howard. 1993. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Rucht, Dieter. 2000. “Distant Issue Movements in Germany: Empirical Description and

Theoretical Reflections.” Pp. 76-108 in Globalizations and Social Movements:

Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere, edited by John A. Guidry, Michael D. Kennedy and Mayer N. Zald. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Smith, Jackie. 1998. ‘Global Civil Society?’ The American Behavioral Scientist 42(1),

93-107.

Smith, Jackie, Charles Chatfield and Ron Pagnucco, eds. 1997. Transnational Social

Movements and Global Politics: Solidarity Beyond the State. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Tu, Wei-ming. (1994) ‘Cultural China: The Periphery as the Center’, pp. 1-34 in Tu Wei-

ming (ed) The Living Tree: The Changing Meaning of Being Chinese Today.

Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Walton, Greg. 2001. “China’s Golden Shield: Corporations and the Development of

Surveillance Technology in the People’s Republic of China.” International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development. http://www.ichrdd.ca/frame.iphtml?langue=0. Retrieved 04/12/2002.

Warkentin, Craig and Karen Mingst. 2000. “International Institutions, the State, and

Global Civil Society in the Age of the World Wide Web.” Global Governance 6(2): 237-257.

Wellman, Barry. 1997. “An Electronic Group is Virtually a Social Network.” Pp. 179-205 in Culture of the Internet, edited by Sara Kiesler. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Xiong Lei. 2001. “Biochemist Wages Online War Against Ethical Lapses.” Science,

Aug 10, Vol. 293 (5532), pp. 1039.

Yang, Guobin. Forthcoming. “The Internet and the Rise of a Transnational Chinese

Cultural Sphere.” Media, Culture & Society.

[1] Examples are the BBSs operated by two North American portal sites, http://www.xys.org and http://www.muzi.com. They are both well-known in China.

[2]http://lundian.com/forum/view.shtml?p=PS200204090830016108&l=chinese . Retrieved April 13, 2002. My own translation.

[3]<http://vm.nthu.edu.tw/ykdoc/hit.html>, retrieved March 31, 2002.

[4]The “educated youth” (or zhiqing) generation is sometimes known as the Red

Guard generation or the Cultural Revolution generation. It refers to the cohort that was sent down to the countryside in the “Up to the Mountains and Down to the Villages” movement. The movement started in 1968 and was officially called off in 1980.

[5]The term “net friend” is commonly used to refer to other net users; it does not denote friendship, although it does sound more friendly than a mere “user.”

[6]All posts were in Chinese. In this article, they are quoted in English translations of my own rendering.