DPRK Renewable Energy Project in the Media

- May 1999: Windpower Monthly

- September 29, 1998: Los Angeles Times

- May 22, 1998: San Francisco Chronicle

- March 20, 1998: Korea Herald

- March 11, 1998: San Jose Mercury News

Building a political bridge with wind

Windpower Monthly, May 1999

The winds of change could be starting to sweep North Korea, albeit only gently. Following the arrival of seven small wind turbines from the US last autumn, the non-profit California group behind the politically inspired project is also planning more energy activity in the famine ravaged country. The wind project is the first non-governmental development by an American group in North Korea, one of the most politically isolated countries in the world. The small turbines are providing electricity for 20 homes, a medical clinic and a kindergarten. Doctors can now refrigerate medicine, farmers can get electric pumps to work, and there are fluorescent lights in the kindergarten reliably for the first time since the country’s economy and electric system declined.

The winds of change could be starting to sweep North Korea, albeit only gently. Following the arrival of seven small wind turbines from the US last autumn, the non-profit California group behind the politically inspired project is also planning more energy activity in the famine ravaged country. The wind project is the first non-governmental development by an American group in North Korea, one of the most politically isolated countries in the world. The small turbines are providing electricity for 20 homes, a medical clinic and a kindergarten. Doctors can now refrigerate medicine, farmers can get electric pumps to work, and there are fluorescent lights in the kindergarten reliably for the first time since the country’s economy and electric system declined.

Not surprisingly, press coverage has been substantial. In the US, articles have appeared in California newspapers and on national public television and radio. Wire services have also carried stories about the ground-breaking project, first publicised about a year ago. At that time, it was expected to involve a single turbine (Windpower Monthly, May 1998). The organiser of the project, the non-profit Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainable Development, says it hopes to return this month to check in on the turbines and to perhaps add a solar cell to take the system off-grid. All small-scale generating technologies, both non-renewable and renewable, including wind, are being considered for the expansion, says Nautilus’ Peter Hayes.

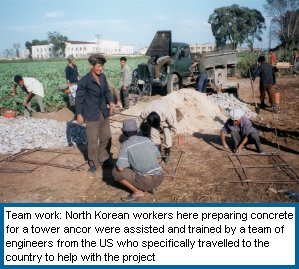

The small 11.5 kW wind plant, which consists of four Whisper units, one Bergey and one Windseeker, was electrified on October 5 after being erected by hand in cabbage fields near the village of Unhari by a bi-national team from the US and North Korea. Construction took five weeks. About 50 North Korean engineers, technicians and labourers were also involved. The project, which is ultimately expected to cost some $400,000, was backed by the W Alton Jones Foundation in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Planning and building the wind project has clearly helped create and strengthen the fragile links between the West and North Korea, most of which is off-limits to outsiders. “The North Koreans wanted this project to succeed,” notes Hayes. “We were allowed to film video and take photos almost without restraint in a highly militarised zone. We went into households and conducted detailed interviews and physical surveys of the use of energy in the village economy.”

Before the project installation, the North Koreans had visited the US, to tour wind and solar plants in California and Colorado, visit the National Renewable Energy laboratory, the Department of Energy and the World Bank, which has since conducted its first ever trip to Pyongyang, North Korea¹s capital. The demonstration project required unusual steps, because of its political sensitivity. The US has had no diplomatic relations with North Korea since the end of the Korean War in 1953. Any US work there is limited in size and scope by the American government, as well as by North Korea. It must be licensed at the US end, and is carefully monitored at the other end, both politically and as it went in the ground. The overall project, because any such work is so sensitive politically, also had to be important enough symbolically to get co-operation between the governments — yet also innocuous and unthreatening to both. It was approved after two years of negotiation partly because it is in keeping with the 1994 Geneva Agreed Framework aimed at ending North Korea¹s program of nuclear weapons.

Through hoops

The turbine towers were made in South Korea, had to be shipped to the US and then back to North Korea to avoid forbidden direct shipment. The only crane large enough for unloading ships, two hours from the capital Pyongyang, was not working. And once the South Korean parts arrived, their names were painted over to hide their origin. Even US newspapers that had been used for packing were discarded as “unsuitable” politically. “The villagers were leery, maybe a little afraid — Americans are sort of cast as the evil princes there,” commented Nautilus¹ renewables expert Jim Williams recently. “It must have been jarring to see representatives of this society bringing light.” Electricity needs in rural North Korea are extremely high, says Nautilus. The country’s economy is collapsing, and the electric grid is probably operating at 50% capacity. Power is often only available regionally and intermittently and with a wildly fluctuating voltage, says Hayes. In addition, even on a per capita basis, power needs are relatively high, he says. For example, electrical equipment is old, so it is inefficient. The village itself, on the western shore about 30 miles north of Nampo City, is in one of the less poor areas of the country. Even so it did not have power, in part because of the ruptured electric system and also because it had been hit hard by a tidal wave in 1997.

The turbine towers were made in South Korea, had to be shipped to the US and then back to North Korea to avoid forbidden direct shipment. The only crane large enough for unloading ships, two hours from the capital Pyongyang, was not working. And once the South Korean parts arrived, their names were painted over to hide their origin. Even US newspapers that had been used for packing were discarded as “unsuitable” politically. “The villagers were leery, maybe a little afraid — Americans are sort of cast as the evil princes there,” commented Nautilus¹ renewables expert Jim Williams recently. “It must have been jarring to see representatives of this society bringing light.” Electricity needs in rural North Korea are extremely high, says Nautilus. The country’s economy is collapsing, and the electric grid is probably operating at 50% capacity. Power is often only available regionally and intermittently and with a wildly fluctuating voltage, says Hayes. In addition, even on a per capita basis, power needs are relatively high, he says. For example, electrical equipment is old, so it is inefficient. The village itself, on the western shore about 30 miles north of Nampo City, is in one of the less poor areas of the country. Even so it did not have power, in part because of the ruptured electric system and also because it had been hit hard by a tidal wave in 1997.

Los Angeles Times

Tuesday, September 29, 1998

Home Edition

Section: Metro

Page: B-7

CALIFORNIA PROSPECT

Commentary

Is Crazy the Only Answer to Crazy?

Congress is on the brink of killing off the last peaceful U.S. ties to North Korea. Then what?

By: TOM PLATE

Times columnist Tom Plate teaches at UCLA. Email: tplate@ucla.edu

In Washington last week, tucked inside the cavernous hearing room of the House International Relations Committee, congressional frustration with the irredeemably difficult North Koreans was on vivid display. Last month, North Korea, always tough to love, rewarded Washington for its dogged diplomatic efforts by firing a satellite-bearing rocket, without so much as a warning, over Japan’s head. Congress then summoned to this hearing America’s hard-pressed negotiators to explain why the North Koreans act the way they do. (Honest answer: No one knows).

In truth, many in Congress, especially Republicans eager to embarrass the Clinton administration for engaging with North Korea, would just as soon bomb the last vestige of orthodox communism back to the Stone Age as spend another dime or minute on negotiations. Of course, due to old-time communist ideology and sheer ineptitude, the North Koreans have never really escaped from the Stone Age–carpet bombing not required.

The only exception to North Korea’s underdevelopment is its overdeveloped, 1.16 million-man military machine, which targets longer range missiles on missile-defenseless Japan and trains artillery batteries on the nearby capital city of the South, Seoul. As a U.S. military source in South Korea explained: “They wouldn’t just pour over the border as foot soldiers. The North’s artillery would rain down on Seoul. Their Rodong missiles would slime the southern cities with chemical agents. North Korean special forces are already in South Korea, and they would do everything from blowing up TV stations to killing South Korean leaders. The North has the ability to threaten South Korea in depth, not just along the DMZ. We’d stop the ground assault–it’s the other stuff that would do the real damage.”

The 1994 negotiations in Geneva that produced the framework governing relations between North Korea and the West didn’t end U.S. economic sanctions, infuriating North Korea. Now, in fact, they might be constructing a secretive, subterranean nuclear project with a reactor perhaps capable of producing nuclear-bomb fuel. If so, that’s it for the Geneva accord, known as the Agreed Framework. Congress won’t continue funding of the deal whereby the U.S. supplies home heating oil in return for which the North agrees not to restart its nuclear weapons program.

With each passing day, that exchange, part of what is called Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization agreement, loses support. Hostile questions that used to be raised only by the dimmer end of the far right, exemplified by Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R-Huntington Beach), are now being raised even by highly respected committee members like Christopher Cox, another Orange County Republican. The current policy is no bargain, but what to put in its place?

“The political posturing to wreck the Agreed Framework is irresponsible in the extreme,” complains a disgusted Peter Hayes, executive director of the Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainable Development, a Berkeley-based nonprofit helping the famine-devastated North Koreans build a wind-powered turbine electricity system. Before leaving for North Korea last weekend, Hayes commented: “It makes it much harder to engage them cooperatively–to test their will to work cooperatively with the United States, instead of having to rely solely on conventional military threats and nuclear extortion as its means of communicating with the United States. Dumping KEDO sounds smart until you examine the alternatives. When the Republicans look over the precipice, they will conclude that jumping over cliffs is bad for your health.”

Well, maybe. At the pivotal though sparsely attended House hearing last week, Republicans, who control the committee, complained that the negotiations with North Korea were being conducted on too low a level. Frustrated Defense Department official Kurt Campbell pointed out that top North Korean officials, including national leader Kim Jong-il, are rather anti-social, if not wholly closed off to the West: “There is no person in the world we know less about.” To which wise-cracking New York Democrat Gary Ackerman added: “So where is Kenneth Starr when we need him?”

Sure. But all joking aside, the Lewinsky mess has made official Washington more meanly partisan than at any time in memory. Even though the South Korean government itself is begging Congress to stay the course–to keep negotiating with the North, as frustrating for all as it is–the Republicans may still wind up killing KEDO and the Agreed Framework. In its place, they have nothing to propose more substantive than a commission to study the issue. Brilliant. Said a U.S. diplomat at the hearing: “This whole thing makes me sick, it’s become so partisan.” After the hearing, a stoic but clearly dejected U.S. diplomat, caught between the lines of North Korea and Congress, was asked how he felt about having to negotiate with a “completely insane government”–meaning, of course, North Korea. Not missing a beat, the diplomat replied: “Which one?”

Type of Material: Opinion Piece

Copyright (c) 1998 Times Mirror Company

Note: May not be reproduced or retransmitted without permission. To talk to our permissions department, call: (800) LATIMES, ext. 74564. Choose extension 0 for other questions.

San Francisco Chronicle

Lewis Dolinsky

NOTES FROM HERE AND THERE: A HAT CAN WORK WONDERS IN NORTH KOREA

Neither North Korea nor the United States is living up to the spirit of the understanding signed in 1994 as an alternative to war. The North shut down two nuclear reactors, and the United States agreed to supply a half-million tons of fuel yearly until it can have two (relatively harmless) light-water reactors completed in the North. But there are grievances on both sides, and recently North Korea threatened to unfreeze its nuclear plants.

In this context, Peter Hayes, co- director of Berkeley’s nonprofit Nautilus Institute, and three other engineers from the United States spent last week in North Korea, helping to construct a 100-foot wind tower in a 600-household village in Onch’on County, a rural area where farmland was inundated by a 25-foot tidal wave last year. To Hayes, an Australian who has studied, written about and visited the Koreas since the late 1970s, it was remarkable how three American engineers meshed with their 16 North Korean partners — despite barriers of language, culture, fear and animosity — and got the job done. All in five days.

Hayes says hats broke the tension. Everyone on the site, even the military police and farmers, wore blue baseball caps with “Nautilus” and “wind power” written in English and Korean. And at the end of a tough day, there were handshakes, smiles and fiery rice liquor.

The North Koreans adapted quickly, but they are used to working fast, without tools and under hazardous conditions. Hayes’ first priority had to be safety. If anyone in his group were hurt, it would take a week to get out of the country; if any Koreans were hurt, confidence in the Americans, and in the project, would be destroyed.

After the binational teams raised the tower, they installed wind-measuring meters and microelectronic readout equipment. The Nautilus group will be back to help install a turbine, build six more towers and extend wire so that power will go to a kindergarten and a medical clinic, and later to houses.

Part of the process is teaching fuel efficiency. The Nautilus project may be the first in keeping with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act passed by Congress in 1978, which authorized the export of renewable energy technology to encourage nations to give up nuclear weapons programs. Every detail had to be vetted by both governments. The cost (paid by the W. Alton Jones Foundation in Charlottesville, Va.) was $250,000, including insurance, travel, food, hardware and good will. Sounds like a bargain.

Onch’on, poor but not starving, is a 1 1/2-hour drive from the capital, Pyongyang, and the route took Hayes past a port where international food aid arrives. He saw children waiting in the road for any bit of grain that might fall off a truck.

U.S. Group to Help Set Up Wind Power Plant in North Korea

Korea Herald

A 15kw-level wind power plant will likely be established in North Korea with the support of an American research institute this year.

Green Korea, a South Korean environmental group, said yesterday that the power plant will be set up in Onchon County, southwest of Pyongyang.

According to the environmental group, the Nautilus Institute, which specializes in research on Northeast Asia’s energy and environmental issues, recently sealed an agreement with the North Korean Anti-Nuclear Peace Committee.

The ground for the project will be broken by May and the electricity generated by the plant will be used for hospitals, schools, houses and farming facilities in the area. Onchon County is a flat plain that has been plagued by frequent floods.

“The envisaged wind power plant is relatively small in scale, so the construction could be completed within this year,” said a Green Korea official.

The funds required for the construction will be raised in the United States by the Nautilus Institute.

The project was conceived last November, when Dr. Peter Hayes, a co-head of the Nautilus Institute and leader of the project, invited some high-ranking North Korean officials to the United States. Among those that came were Choi Chang-hoon, secretary-general of the North Korean Anti-Nuclear Peace Committee.

With the help of the institute, the North Korean delegation toured various energy-related facilities and power plants in the U.S. and talked over the North’s energy problems with U.S. government officials.

Dr. Hayes plans to come to Seoul before visiting the North at the end of next month in order to discuss ways to create more cooperation between the two Koreas in the field of energy development.

In terms of a humanitarian point of view, the need for energy development is crucial to North Korea argues Doctor Hayes. “North Korea faces serious problems like acid rain, deforestation and pollution by gasoline,” says Doctor Hayes.

This poses as great a risk to the well-being of the North Korean people as having no food, says Chang Won of Green Korea.

North Korea opening door ever so slightly to accept windmills for power

BY T.T. NHU

San Jose Mercury News

SAN JOSE, Calif. — Lest anyone have lingering doubts the Cold War is in the final stages of a thaw, consider this:

In May, with the blessing of the U.S. government, a team of engineers and environmental specialists from the Berkeley-based Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainable Development will travel to North Korea, one of the last hard-line communist nations left on the planet, to install windmills that will produce electricity in villages on the coastal plain southwest of Pyongyang.

The mission, announced Wednesday, follows a unique visit last fall to Berkeley by a delegation of North Koreans eager to learn about solar and wind energy.

It was the first-ever technical training mission in the United States approved by the governments of both the United States and North Korea. The session was sponsored by Nautilus, a research group focused on the intersection of energy, environment and security issues in Asia and the Pacific.

A few days before Thanksgiving last year, the visiting delegation — including three engineers and the secretary general of the Korean anti-nuclear Peace Committee — arrived in Berkeley during a driving rainstorm.

After a punishing 44-hour journey from their homeland, they were whisked by their host, Nautilus director Peter Hayes, for a tempestuous sail beyond the Golden Gate Bridge. The group ate turkey at Thanksgiving and bought Reeboks at a mall and computer books at Cody’s Books. The manager of Andronico’s Supermarket gave them a guided tour of his upscale store, where they were impressed by the abundance of food — and stunned by the rows of cigarettes on the shelves.

The visitors’ amazement was understandable. After a half-century of little communication with the rest of the world other than on a diplomatic level, North Korea is profoundly isolated and has few resources or creature comforts.

But that may change soon.

In 1994, the sequestered country broke out of its seclusion somewhat, thanks to former President Jimmy Carter’s efforts to broker an agreement in which North Korea agreed to freeze its nuclear-weapons program in exchange for light-water reactors that would provide much-needed energy for the beleaguered country.

Although U.S. analysts believe North Korean has enough plutonium to develop a crude nuclear weapon, Hayes thinks the country was a long way from having an operable or deliverable weapon. But he concludes the North Koreans were committed to developing nuclear weapons.

“We’ll never know how close and how far they went,” Hayes said.

Hayes’ involvement in North Korea go back even farther than Carter’s breakthrough. In 1989, the Australian specialist on nuclear and security issues in Asia began receiving invitations from North Korea to share his expertise. The author of Pacific Powderkeg, American Nuclear Dilemmas in Korea (Free Press, 1990) had long been involved in environmental issues in the Pacific and Northeast Asia.

What he found was an isolated nation struggling to feed itself.

The nation was — and is — being devastated by a famine Hayes termed a disaster in the making for four decades.

North Korea is plagued by acid rain, oil pollution and severe deforestation that has led to floods, drought and widespread hunger for its population of 22 million. Having pledged to halt its nuclear program, it must now look for other sources of energy.

“The famine is an important opportunity for both sides — North and South Korea and the United States to move ahead,” said Hayes. Bringing the North Korean team to work on developing renewable energy is one such opening.

As Phase I of the project, the North Korean team toured wind and solar-power plants in California and Colorado, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Boulder and the Department of Energy in Washington D.C.

They also dropped in at the World Bank for a meeting that resulted in a World Bank mission to Pyongyang, the first ever in North Korea.

In the final days, at a hands-on workshop in the yard of Nautilus in Berkeley, the North Koreans put together a wind-powered system with the guidance of American wind-turbine engineers.

Phase II will be the visit to North Korea in May to install full-scale wind turbines.

Former Cold Warrior Robert Scalapino, for one, believes the mission has a chance to help bring North Korea into the free market that dominates the rest of the world.

“Nautilus does useful work concentrating on energy, which … enables North Korea to make policy change via small energy projects,” he said.

Scalapino is emeritus professor of political science at U.C. Berkeley and sometime adviser to the Nautilus Institute. Once a strident critic of hard-line Marxist societies, Scalapino has mellowed after visiting the countries he once condemned — China, Vietnam and North Korea.

“I came away from North Korea with this feeling it wasn’t a revolutionary society,” said Scalapino. “It was a traditional society with one party and a leadership that had a religious aura backed by a strong military. The aloofness, the isolation, the very rudimentary lifestyle was a confirmation of my assumptions that Korea wasn’t this monolith we’d built it up to be. In private conversations, people could drop the polemics and speak in realistic terms about their national concerns.”

The alternative-energy project is a significant indication North Korea is acknowledging its national concerns and accepting its involvement with the rest of the world, according to Scalapino.

“Policy shift is taking place right before our eyes,” he said.