RAMESH THAKUR

JANUARY 9, 2018

I. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, Ramesh Thakur notes that “in 50 years, not one nuclear warhead has been eliminated as the result of a bilateral or multilateral agreement concluded under the NPT’s authority. This proven ineffectiveness has discredited the NPT as the sole disarmament framework and fed the exasperation behind the international community’s disarmament breakout through a UN nuclear ban treaty that stigmatizes and prohibits the bomb. The new legal architecture for disarmament is a circuit-breaker in the search for a dependable, rules-based security order outside the limits of what the nuclear-armed countries are prepared to accept because disarmament is of lower priority for them than bolstering and sustaining deterrence indefinitely. The next four priorities are to increase the signatories to all the 122 states that adopted the treaty, to lobby the signatory states to ratify the treaty to bring it into force, to increase the ratifying number to 100 to generate additional normative pressure, and to wean away some NATO and Pacific allies from their dependence on extended nuclear deterrence into signing the ban treaty.”

Ramesh Thakur is professor in the Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University and Co-Convenor of the Asia–Pacific Leadership Network on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament. This paper is published simultaneously as Asia Pacific Leadership Network Policy Brief 54 here.

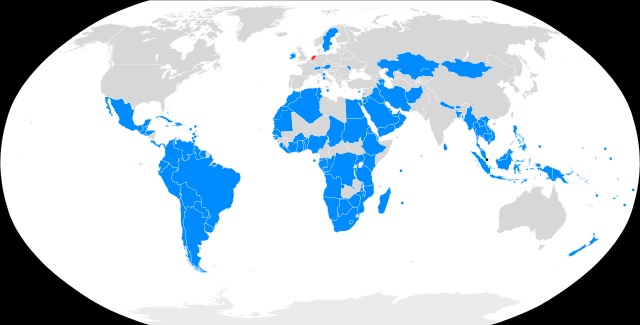

Banner image: votes on treaty text Nuclear Weapons Prohibition Treaty negotiations July 7 2017 from Karte: NordNordWest, Lizenz: Creative Commons by-sa-3.0 de found here.

II. NAPSNET POLICY FORUM BY RAMESH THAKUR

NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT, THE NPT AND THE BAN TREATY: PROVEN INEFFECTIVENESS VERSUS UNPROVEN NORMATIVE POTENTIAL

JANUARY 9, 2018

1. On 26 January 2017, the famous Doomsday Clock moved to 2.5 minutes to midnight – the closest to zero hour since 1953.[1] Four big nuclear storylines dominated the year that followed: the becalmed state of nuclear arms control; the adoption of a new UN ban treaty; the start of the five-yearly review cycle for the existing Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); and North Korea. The clock may well move forward again in January 2018. For a nuclear war, although still not probable, is now a distinct possibility, if not by design then by accident, system malfunction, cyber-terrorism, faulty information or rogue launch.

Background: Persisting and Elevated Nuclear Threats[2]

2. In 2017, there were around 15,000 nuclear weapons held in the arsenals of nine countries (China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, UK, and USA). On the one hand, nuclear threats acquired fresh prominence with continuing volatility and geopolitical tensions in eastern Europe, the Middle East, South and East Asia. On the other hand, to the incredulity of increasingly worried people, there were absolutely no discussions being held between any two or more of the ‘nuclear nine’ on new and additional measures to regulate and reduce their stockpiles. Instead, existing agreements were being allowed to expire to the point where a respected Russian nuclear policy expert, Alexei Arbatov, wondered if nuclear arms control had reached its own end of history.[3]

3. Nuclear weapons are the ultimate weapons of war and therefore the ultimate weapons to prevent (the deterrence argument) and avoid (the abolition argument) war either by design or inadvertently. This two-axis struggle is captured in the two parallel treaties for setting global nuclear norms and policy directions. Only time will tell if they turn out to be complementary, competing or even mutually undermining.

4. The 2015 Iran nuclear deal[4]and North Korea’s unchecked nuclear and missile delivery advances show the benefits and limitations of the NPT respectively. The transparency, verification and consequences regime mothballed Iran’s bomb-making program by enforcing its NPT non-proliferation obligations. These will remain legally binding even after the deal expires in 2030. By contrast, the crisis over North Korea’s nuclear program has intensified within the NPT framework and the international community has found it difficult to establish Pyongyang’s precise legal status vis-à-vis the NPT. Thus although North Korea withdrew from the treaty in 2003 and has acquired a weaponized intercontinental nuclear capability, the UN website still lists it as a State Party.[5]

5. The Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) process for the 2020 NPT Review Conference began with the first meeting in Vienna on 2–12 May. The 2020 Conference will mark the 50th anniversary of the NPT entering into force. Yet in 50 years that the NPT has been in existence, not a single nuclear warhead has been eliminated as the result of a bilateral or multilateral agreement concluded under the authority of the NPT. The approximately 80 per cent reduction in global nuclear warhead stockpiles since the Cold War peak in the mid-1980s has resulted entirely form unilateral measures or bilateral US–Soviet/Russian agreements.

6. This is despite the legal obligation in Article VI of the NPT for every State Party (not just the nuclear powers) to negotiate effective measures towards nuclear disarmament at an early date. The stalemate on nuclear disarmament has gradually discredited the NPT as the sole disarmament framework and fed the exasperation behind the international community’s disarmament breakout through the ban treaty instead. This also explains why the main criticism levelled at the swelling surge in support for closing the legal gap on prohibition – that without the nuclear powers, it would be ineffectual virtue signalling – failed to get any traction beyond the possessor and umbrella states. The latter were defending a treaty of proven ineffectiveness on nuclear disarmament.

7. The prohibition treaty champions’ minds were further concentrated during 2017 as North Korea made unexpectedly rapid gains in the number of its nuclear warheads, intercontinental missile delivery capability, and warhead miniaturization capabilities. The tweet-prone, erratic and strategically-challenged US President Donald Trump further inflamed tensions on the Korean Peninsula by exchanging a series of escalating threats and counter-threats with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un. With Pyongyang having pulled out of the NPT in 2003 and conducted six nuclear tests from 2006 to 2017, this is a nuclear crisis made entirely and exclusively within the NPT regime as telling proof of the treaty’s inadequacy. Having instrumentalized the NPT as a solely non-proliferation tool instead of a reciprocal disarmament obligation, the nuclear powers were trapped in their own hypocrisy in dealing effectively with the challenge from North Korea. By the time of the next NPT Review Conference in 2020, the world will either have accepted North Korea as a de facto nuclear-armed state, or it might be an active war zone, or else it might have been reduced to an atomic wasteland the likes of which we have not seen before.

Humanitarian Imperatives

8. Increasingly exasperated at the lack of nuclear disarmament anytime soon, driven by fear of a catastrophic nuclear war with incalculable humanitarian consequences if nuclear weapons are not abolished, and inspired by humanitarian principles, a growing number of non-nuclear weapon states joined with civil society actors to explore an alternative avenue. In the 1996 World Court Advisory Opinion,[6] most judges believed that any use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to international and in particular humanitarian law, violating the principles of necessity, proportionality, civilian-combatant distinction, and the need to avoid superfluous injury and unnecessary suffering. In addition, they could not conclude definitively that the use of nuclear weapons would be justified in self-defence even if the very survival of the state was threatened.

9. The 1996 Advisory Opinion also significantly altered the nature of disarmament obligations from a commitment to pursue negotiations, into an obligation “to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion” such negotiations (emphasis added). On this, the 14-judge Court was unanimous: judges from every nuclear weapon state agreed with this fundamental obligation. Yet, 22 years later, not only do nine countries still possess nearly 15,000 nuclear weapons in their arsenals; all of them are modernizing, upgrading or expanding nuclear-weapon delivery platforms and the four Asian nuclear powers – China, India, North Korea, Pakistan – are even enlarging stockpiles.

10. Against the twin backdrop of the receding nuclear arms control and disarmament tide, and elevated nuclear threat levels, many countries concluded that for all its very substantial and invaluable security achievements and benefits, the NPT’s normative potential had been exhausted in unleashing dramatic nuclear disarmament measures because the nuclear nine were caught in the trap of basing their nuclear policies solely within national security paradigms. The normative basis for the new initiative was humanitarian principles which permit advocates to transcend national and international security arguments.

11. The essence of the humanitarian consequences movement that surged over 2013–15 can be summarized in three propositions:

- No country individually, nor the international system collectively, has the physical and organizational capacity to cope with the humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons.

- It is in the interests of the very survival of humanity that nuclear weapons are never used again, under any circumstances.

- The only guarantee of non-use is the total, irreversible and verifiable elimination of nuclear weapons

The Ban Treaty

12. Meeting under UN auspices in New York, on 7 July 122 states adopted a nuclear ban treaty that stigmatizes and prohibits the bomb (ownership, development, manufacture, testing, use, threat of use etc.) for all countries.[7] Which is why it was opposed unanimously by all nine possessor countries, and also by all the NATO allies in Europe whose security doctrine includes the nuclear deterrent as a core component, and the three US allies in the Pacific (Australia, Japan, South Korea) who too rely for their security on US extended nuclear deterrence. The treaty was opened for signature in the United Nations General Assembly on 20 September and by year’s end had been ratified by four countries and signed by another 49. It will come into effect 90 days after 50 states have ratified. There is little real doubt that this will happen, probably sooner rather than later.

13. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is the first to ban the possession, transfer, use and threat of use of nuclear weapons. This completes the legally binding prohibition of all three classes of weapons of mass destruction, after biological and chemical weapons were banned by universal conventions in 1972 and 1993 respectively. Like the NPT, the ban treaty is legally binding only on signatories. Unlike the new treaty, which applies equally to all signatories, the NPT granted temporary exemptions for the continued possession of nuclear weapons by the five nuclear weapon states that already had them in 1968, but banned proliferation to anyone else.

14. This is also the first occasion in which states on the periphery of the international system have adopted a humanitarian law treaty aimed at imposing global normative standards on the major powers. The major principles of international, humanitarian and human rights laws have their origins in the great powers of the European international order that was progressively internationalized.[8] Ban treaty supporters include the overwhelming majority of states from the global South and some from the global North (Austria, Ireland, New Zealand, Switzerland). The treaty’s opponents include all nine nuclear weapons possessing states, all NATO allies, and Australia, Japan and South Korea. Thus for the first time in history, the major powers and most Western/Northern countries find themselves the objects of an international humanitarian treaty authored by the rest who have framed the challenge, set the agenda and taken control of the narrative.

15. The lead role in civil society was played by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear weapons (ICAN). Nuclear weapons are uniquely destructive and hence uniquely threatening to all our security. ICAN was established in the belief that there is a compelling need to challenge and overcome the reigning complacency on the nuclear risks and dangers, to sensitize policy communities to the urgency and gravity of the nuclear threats and the availability of non-nuclear alternatives as anchors of national and international security orders.

16. ICAN is a coalition of over 450 organizations in more than 100 countries. It was launched in Melbourne on 23 April 2007, consciously modelled on the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) which had won the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of its lead role in mobilizing civil society activism and like-minded governments led by Canada. The transformation of anti-nuclear movements into coalitions of change requires a similar shift from street protest to engagement with politics and policy and that is exactly what ICAN did as a global coalition. On 6 October, the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to ICAN in recognition of its decade-long “ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition” of nuclear weapons by drawing “attention to the catastrophic consequences of any use” of these weapons.[9]

17. Like the ICBL, ICAN – headquartered in Geneva – has forged an effective partnership with the Red Cross. Its website explains how ICAN served as the civil society coordinator for the three humanitarian consequences conferences in 2013–14, lobbied to establish a special UN open-ended working group on nuclear disarmament (A/RES/70/33, 7 December 2015), campaigned for the UN General Assembly’s 23 December 2016 resolution to launch negotiations on a prohibition treaty (A/RES/71/258), and was an active presence at the ban treaty negotiating conference in March and June–July 2017.[10]

18. The Nobel Peace Prize will help to raise the global profile of all three of ICAN, the ban treaty and the cause of nuclear disarmament. For example ICAN decided that the prize would be received jointly on 10 December in Oslo by its executive director Beatrice Fihn and a Hiroshima survivor Setsuko Thurlow who has lived in Toronto since 1955 and been a prominent pubic campaigner for the cause. On 27 October, Canada’s national newspaper carried a prominent story about her and her call on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to sign the ban treaty.[11] Meanwhile in Australia the Turnbull government conspicuously failed to congratulate ICAN, despite the very strong Australian content of its global identity.

Umbrella States

19. The nine nuclear powers and all the NATO and Pacific allies who shelter under US extended nuclear deterrence dismissed the treaty as impractical, ineffective and dangerous. The ban treaty is not compatible with nuclear sharing by NATO allies whereby nuclear weapons are stationed on their territory,[12] nor with Australia’s policy of relying on US nuclear weapons for national security and nuclear-related co-operation with the US through the shared Pine Gap asset. In a period of power transition in which China’s geopolitical footprint is growing,[13]while the US strategic footprint recedes, reliance on the security and political roles of US nuclear weapons by Australia, Japan and South Korea has increased, not diminished.

20. The most strident criticisms of the nuclear diplomatic insurgency have come from France, UK and US, while Australia has been among “the most outspoken of the non-nuclear states” in attacking the special UN conference that negotiated the ban treaty, instead of engaging with the countries that possess nuclear weapons.[14] These critics argue that nuclear deterrence has kept the peace in Europe and the Pacific for seven decades. By contrast, they allege, the ban treaty is a distraction that ignores international security realities, will damage the NPT and could generate fresh pressures to weaponization in some umbrella nations. It ignores the critical limitations of international institutions for overseeing and guaranteeing abolition and has polarized the international community.[15] Consequently it undermines strategic stability, jeopardizes nuclear peace and makes the world more unpredictable.

21. Like the nine possessor states directly, the umbrella states’ preferred approach does not challenge the social purposes and value of nuclear weapons nor question the legality and legitimacy of these weapons and the logic and practice of nuclear deterrence. It leaves nuclear agency entirely in the hands of the possessor states, accepting that they can safely manage nuclear risks by appropriate adjustments to warhead numbers, nuclear doctrines and force postures.

22. For Australia and Japan, nuclear disarmament is of lower priority than bolstering and indefinitely sustaining the legitimacy and credibility of nuclear deterrence. In their view, the ban treaty will neither promote global nuclear disarmament nor strengthen national security. Their instinct is to support incremental, verifiable and enforceable agreements and commitments but there is no detailed framework for actual elimination, verification and enforcement in the ban treaty. Australia’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paperrepeats the familiar mantra that a complex security environment requires a patient and pragmatic approach. It simply ignores the adoption of the ban treaty, pretending it does not exist.[16]

Normative Impact

23. The nuclear ban treaty is a good faith effort by 122 countries to act on their NPT responsibility to take effective measures on nuclear disarmament. To nuclear deterrence critics, the nuclear powers are not so much possessor as possessed countries. Within the security paradigm, nuclear weapons are national assets for the possessor countries individually. In the ban treaty’s humanitarian reframing, they are a collective international hazard. The known humanitarian consequences of any future use makes the very possibility of nuclear war unacceptable. Dispossession of nuclear weapons removes that future possibility.

24. The nuclear weapon states have instrumentalized the NPT to legitimize their own indefinite possession of nuclear weapons while enforcing non-proliferation on anyone else pushing to join their exclusive club. For them, the problem is who has the bomb. But increasingly in the eyes and minds of anti-nuclear advocates, the bomb itself is the problem. The ban treaty is a circuit-breaker in the search for a dependable, rules-based security order outside the limits of what the nuclear-armed countries are prepared to accept. The step-by-step approach adopts a transactional strategy to move incrementally without disturbing the existing security order. The ban treaty’s transformative approach transcends the limitations imposed by national and international security arguments.

25. Stigmatization and prohibition are normative steps on the path to nuclear disarmament. The nuclear disarmament goals are to delegitimize, prohibit, cap, reduce, and eliminate. Only those possessing nuclear weapons can undertake the last three tasks and the report of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament (ICNND) had already outlined pathways where the non-proliferation and disarmament goals of the NPT and ban treaty converge.[17] But the non-possessor states can pursue the first (delegitimization) and second (prohibition) goals on their own to exert pressure on possessor states to pursue the other three goals. Thus stigmatization and prohibition are the necessary, although not sufficient, precursors to elimination. Moreover, the treaty will also draw on the UN’s unique role as the sole custodian and dispenser of politically significant approbation and anathematization of state conduct.[18] If we update Claude’s thesis to contemporary conditions, in recent times the General Assembly has asserted itself as the normative centre of gravity against the increasingly anachronistic Security Council as the geopolitical centre of gravity, for example in choosing the ninth Secretary-General and the success of an Indian against a British candidate for election to the International Court of Justice.[19]

26. The main impact of the nuclear ban treaty will be to reshape the global normative milieu: the prevailing cluster of laws (international, humanitarian, and human rights), norms, rules, practices and discourse that shape how we think about and act in relation to nuclear weapons. Criticism of the ban treaty deliberately but misleadingly confuses the normative impact of a prohibition treaty with the operational results of a Nuclear Weapons Convention. Stigmatization implies illegitimacy of a practice based on the collective moral revulsion of a community. The ban treaty aims to delegitimize and stigmatize the possession, use and deployment of nuclear weapons, plus the practice of nuclear deterrence, owing to the risks of possession and the humanitarian consequences of any use. The foreseeable effects of use makes the doctrine of deterrence and the possession of nuclear weapons morally unacceptable to the international community.

27. The ban treaty is not a magic wand that can be waved to make all nuclear weapons vanish. But the normative impact will lessen their attractiveness and change the incentive structures for states that possess them and others that rely on extended nuclear deterrence. The 1997 Ottawa Convention prohibiting antipersonnel landmines too is better understood as a humanitarian than an arms control treaty.[20] The big producers and users are not parties yet few officials of the non-parties would dispute that it has shaped their states’ behaviour. The late International Relations scholar Hedley Bull noted that “great powers are powers recognised by others to have, and conceived by their own leaders and peoples to have, certain special rights and duties.”[21] The NPT recognized the major powers’ right to possess nuclear weapons as part of their special managerial responsibilities for world order; the leaders the NWS continue to assert that right; but in the ban treaty, international society has derecognized the right.

28. By changing the prevailing normative structure, the ban treaty shifts the balance of costs and benefits of possession, deterrence doctrines and deployment practices and will create a deepening crisis of legitimacy. It removes the fig-leaf of international legitimacy, rooted in the NPT, that the nuclear weapon states have used in which to cloak their nuclear weapons, while insisting that the pursuit of nuclear weapons by anyone else is both illegal (a violation of the law of treaties) and illegitimate (a violation of the global norm against nuclear weapons).

29. Because the nuclear-armed states boycotted the ban conference and refuse to sign the treaty, it will have no immediate operational effect. But because it is a UN treaty adopted by a duly constituted multilateral conference, it will have normative force. The ban treaty will reshape how the world community thinks about and acts in relation to nuclear weapons as well as those who possess the bomb. It strengthens the norms of non-proliferation and those against nuclear testing, reaffirms the disarmament norm, rejects the nuclear deterrence norm, and articulates a new universal norm against possession.

What Next?

30. The fraying normative consensus around the NPT as the embodiment of the global nuclear order and the framework for setting global nuclear policy directions has been broken. In the short term, the nuclear-armed states may well ignore the ban treaty to double down on investment in nuclear weapons, doctrines and deployment practices. But the NPT’s five NWS will no longer be able to claim the mantle of international legality and legitimacy that the NPT had conferred on their possessor status. They may not like the result, but their constant refrain that the nuclear genie cannot be put back in the bottle is now turned against them: neither can the ban treaty.

31. Critics allege that another landmark agreement in history was the war-renouncing Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928 that proved utterly ineffectual. True, but there is one critical difference. That pact was entirely voluntary, whereas the ban treaty is legally binding – that is the whole point of the treaty. Once in force, it will become part of the legal architecture for disarmament and all countries must adjust to the new institutional reality.

32. It remains to be seen if the ban treaty will spur the nuclear weapons possessing states to implement such nuclear risk reduction measures as adoption of no-first-use policies, taking all weapons off high-alert status where they can be launched within minutes and therefore put the world at the risk of a nuclear war launched by blips on the radar screen, bringing the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty into force, adopting a new fissile materials cut-off treaty, extending the Russia–US New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, and commencing new negotiations on additional drastic cuts to existing stockpiles.

33. The second PrepCom and the UN-mandated High-Level Conference on Disarmament will provide structured opportunities in April–May 2018 for ban treaty champions and critics to find common ground in the shared objectives of nuclear non-proliferation, safety, security, testing and disarmament. Unless they would rather go over the nuclear cliff, a constructive approach would be for like-minded countries like Australia, Canada, Japan and Norway to lead a collaborative effort to explore strategic stability at low numbers of nuclear weapons and the conditions for serious and practical steps towards nuclear disarmament.

34. The existence of the UN ban treaty has created a new political reality. Part of the required readjustments will include not just managing relations between the NPT and the ban treaty, and between the ardent supporters and vehement critics of the latter. In addition, it will require managing intra-European Union and intra-alliance relations and also domestic demands and expectations. As long as nuclear weapons are integral to NATO’s mission and security-cum-operational doctrine, NATO membership cannot be compatible with the core obligations of the ban treaty. But significant domestic constituencies in several alliance members will continue to demand signature of the ban treaty and the only credible route to defusing their demands will be to demonstrate continued concrete progress on nuclear disarmament.

35. Hitherto nuclear deterrence has been privileged absolutely over calls for disarmament. The explanation provided for lack of credible disarmament progress has been the adverse regional and international security environments. Henceforth the publics in many NATO members will demand that the nuclear-armed states take the necessary steps to create the more favourable security conditions to reduce nuclear risks and facilitate practical nuclear arms control and disarmament measures.

36. Meanwhile the ICAN-led effort is likely to focus on immediate, medium and long term priorities. The first is to increase the number of signatories to the full 122 states that adopted the treaty in the historic vote on 7 July 2017 at the United Nations in New York. The second urgent goal will be to lobby to have the signatory states ratify the treaty so that it enters into force 90 days from the date of the 50th ratification. While this will be sufficient to bring the treaty legally into force, the key psychological threshold for generating normative impact will be 100 ratifications, so that should be the third task in the months and years ahead.

37. A fourth priority should be to try and wean away some of the NATO and Pacific allies from their dependence on extended nuclear deterrence into signing the ban treaty. There are three groups of states on which ICAN should concentrate its efforts. The first is the usual cohort of like-minded internationally progressive states, such as Canada and Norway, that have historically acted together on progressive causes, including arms control. International pressure will be less efficacious than identifying and accessing points of pressure within the domestic politics of each country: mobilize the citizens and then identify the political parties and candidates most receptive to the prohibition message, then support their campaigns. The next will be allies who have traditionally formed the ant-nuclear front within NATO as a nuclear alliance, for example Germany and Canada. The tactics and strategy should be the same as with the third group.

38. The third category is the singular example of Japan as the only country to have been the victim of the use of nuclear weapons with a solid anti-nuclear public constituency as a result. The government’s policy of opposition to the ban treaty is more strongly out of alignment with public opinion in Japan than in any other country.[22] Given the prime minister’s seemingly unassailable dominance in Japan’s political landscape, this gives opposition politicians and parties one major point of differentiation with the ruling party that will be popular with the citizens.

39. At some stage ban treaty supporters will also have to consider how best to engage the possessor countries. The latter badly misjudged the gathering international grievance against their self-centred insistence on indefinite retention of the bomb. Nonetheless, for all its virtue signalling as an authoritative promulgation of a new norm against possession, use and threat of use, operationalization of the ban treaty requires action by the possessor countries. The normative weight might lie with the non-possessor countries through sheer weight of numbers, but the geopolitical clout still resides in the major powers. For the foreseeable future most of them will remain impervious to all efforts to name and shame. Even to capture their attention, an urgent priority for ban treaty advocates, including but not limited to ICAN, should be to recruit a credible state champion. Without one, it is far more challenging to convert innovative ideas for improved global governance into practical policy recommendations and action items.

III. ENDNOTES

[1] “2017 Doomsday Clock Statement,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 26 January 2017, http://thebulletin.org/sites/default/files/Final%202017%20Clock%20Statement.pdf.

[2] This Brief draws and builds on two recently published journal articles: Ramesh Thakur, “The Nuclear Ban Treaty: Recasting a Normative Framework for Disarmament,” The Washington Quarterly 40:4 (Winter 2018), pp. 71–95, https://twq.elliott.gwu.edu/nuclear-ban-treaty-recasting-normative-framework-disarmament; and Ramesh Thakur, “Japan and the Nuclear Weapons Prohibition Treaty: The Wrong side of History, Geography, Legality, Morality and Humanity,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 1:1 (March 2018), http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/25751654.2018.1407579.

[3] Alexei Arbatov, An Unnoticed Crisis: The End of History for Nuclear Arms Control? (Moscow: Carnegie Moscow Center, 2015), http://carnegieendowment.org/files/CP_Arbatov2015_n_web_Eng.pdf.

[4] “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action,” https://www.state.gov/e/eb/tfs/spi/iran/jcpoa/.

[5] United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, “Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons: Status of the Treaty,” http://disarmament.un.org/treaties/t/npt.

[6] International Court of Justice, “Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons: Advisory Opinion,” http://www.un.org/law/icjsum/9623.htm.

[7] Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, http://undocs.org/A/CONF.229/2017/8.

[8] See Ramesh Thakur, “Global Norms and International Humanitarian Law: An Asian Perspective,” International Review of the Red Cross 83: 841 (March 2001), pp. 19–44.

[9] Beatrice Fihn, Matthew Bolton and Elizabeth Minor, “How We Persuaded 122 Countries to Ban Nuclear Weapons,” Just Security, 24 October 2017, https://www.justsecurity.org/46249/persuaded-122-countries-ban-nuclear-weapons/.

[11] Laura Stone, “Canadian woman who survived Hiroshima bombing urges change of heart from Trudeau,” Globe and Mail, 27 October 2017, https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/canadian-woman-who-survived-hiroshima-bombing-urges-change-of-heart-from-trudeau/article36725770/.

[12] The total number of NATO nuclear weapons stationed in non-nuclear weapon states in Europe is 160-240: Belgium 10-20, Germany 20, Italy 70-90, Netherlands 10-20, Turkey 50-90.

[13] Ramesh Thakur, “China’s New World Order?” Project Syndicate, 10 November 2017, https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/china-s-new-world-order-by-ramesh-thakur-2017-11?barrier=accesspaylog.

[14] Ben Doherty, “UN panel releases draft treaty banning possession and use of nuclear weapons,” Guardian, 23 May 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/23/un-panel-releases-draft-treaty-banning-possession-and-use-of-nuclear-weapons.

[15] See the collection of essays in Shatabhisa Shetty and Denitsa Raynova, eds., Breakthrough or Breakpoint? Global Perspectives on the Nuclear Ban Treaty (London: European Leadership Network, 2017), https://www.europeanleadershipnetwork.org/report/breakthrough-or-breakpoint-global-perspectives-on-the-nuclear-ban-treaty/.

[16] 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper (Canberra: Government of Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2017), pp. 83–84, https://www.fpwhitepaper.gov.au/.

[17] Eliminating Nuclear Threats: A Practical Agenda for Global Policymakers (Canberra and Tokyo: ICNND, 2009).

[18] See Inis L. Claude, The Changing United Nations (New York: Random House, 1967), p. 73.

[19] See Ramesh Thakur, “Choosing the Ninth United Nations Secretary-General: Looking Back, Looking Ahead,” Global Governance 23:1 (2017), pp. 1–13; and Ramesh Thakur, “Revolt of the plebs,” The Strategist, 19 December 2017, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/revolt-of-the-plebs/.

[20] Ramesh Thakur and William Maley, “The Ottawa Convention on Landmines: A Landmark Humanitarian Treaty in Arms Control?” Global Governance 5:3 (1999), pp. 273–302.

[21] Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics (London: Macmillan, 1977), p. 202. Emphasis added.

[22] See Thakur, “Japan and the Nuclear Weapons Prohibition Treaty.”

IV. NAUTILUS INVITES YOUR RESPONSE

The Nautilus Asia Peace and Security Network invites your responses to this report. Please send responses to: nautilus@nautilus.org. Responses will be considered for redistribution to the network only if they include the author’s name, affiliation, and explicit consent