Regional Responses to Extra-Territoriality and Non-State Nuclear Actors: A Perspective From Southeast Asia

Raymund Jose G. Quilop

May 5, 2011

This is a paper from the Nautilus Institute workshop “Cooperation to Control Non-State Nuclear Proliferation: Extra-Territorial Jurisdiction and UN Resolutions 1540 and 1373” held on April 4th and 5th in Washington DC with the Stanley Foundation and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. This workshop explored the theoretical options and practical pathways to extend states’ control over non-state actor nuclear proliferation through the use of extra-territorial jurisdiction and international legal cooperation.

Other papers and presentations from the workshop are available here.

Nautilus invites your contributions to this forum, including any responses to this report.

——————–

CONTENTS

II. Article by Raymund Jose G. Quilop

IV. Nautilus invites your responses

Raymund Jose G. Quilop, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of the Philippines

-“Regional Responses to Extra-Territoriality and Non-State Nuclear Actors: A Perspective From Southeast Asia”

The question that begs to be answered therefore as conceptualized in this workshop is whether states, specifically those which have developed their respective national legislations to prevent terrorists from having access to WMD and related materials and technologies, could enforce those legislations beyond the boundaries of their respective territories? Strengthening national controls to prevent terrorists from having access to WMD and related materials and technologies may be relatively easy (although of course several states to date still find it difficult to strengthen those controls) but enforcing such controls may be difficult particularly if such enforcement action goes beyond the immediate territory of a particular state, so the workshop concept paper rightfully notes. The situation becomes more complicated in cases where a state becomes uncooperative as the regards the application of another state’s counter terror actions on its territory.

Nonetheless, there are certain developments within Southeast Asia, specifically among members of ASEAN that are positive and may pave the way for a more substantive implementation of UN SC Resolution 1540 including the possible exercise of extra-territorial jurisdiction over the long term.

not to develop, manufacture or otherwise acquire, possess or have control over nuclear weapons; station nuclear weapons; or test or use nuclear weapons anywhere inside or outside the treaty zone; not to seek or receive any assistance in this; not to take any action to assist or encourage the manufacture or acquisition of any nuclear explosive device by any state; not to pro-vide source or special fissionable materials or equipment to any non-nuclear weapon state (NNWS), or any NWS unless subject to safeguards agreements with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); to prevent in the territory of States Parties the stationing of any nuclear explosive device; to prevent the testing of any nuclear explosive device; not to dump radioactive wastes and other radioactive matter at sea anywhere within the zone, and to pre-vent the dumping of radioactive wastes and other radioactive matter by anyone in the territorial sea of the States Parties (Center for Non-Proliferation Studies 2008).IV

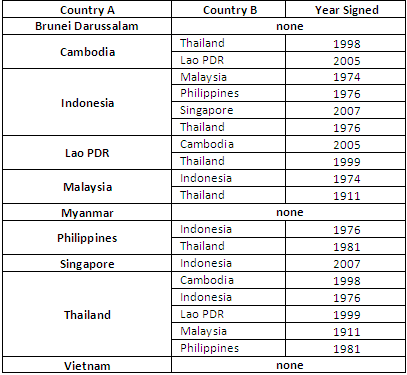

With the realities in Southeast Asia (both constraining and enabling factors mentioned above), what is needed to be done is to move from a tacit recognition of the dangers of non-state actors having access to WMD to explicit action of preventing them from being able to have such an access (Quilop 2008). This could be done by working towards further elevating the issue of WMD proliferation higher in the agenda of ASEAN. Given the ASEAN practice of “moving at a pace comfortable to all”, this could be undertaken by putting this issue as one of the topics in the exchange of views and security outlooks which have become standard in all ASEAN-related meetings, whether foreign affairs initiated or defense ministry-led.Over the long term, extra-territorial jurisdiction could be operationally implemented with the forging of extradition treaties among ASEAN members. To date, Thailand has signed the most number of extradition treaties (with Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia and the Philippines). Indonesia follows with extradition treaties having been signed with Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. The Philippines has extradition treaties with Indonesia and Thailand. Cambodia has signed such treaty with Thailand and Lao PDR while Lao PDR has signed extradition treaties with Cambodia and Thailand. Singapore has extradition treaty solely with Indonesia. Brunei, Myanmar and Vietnam have not signed any such treaty with their ASEAN neighbours. The table below lists the ASEAN members with extradition treaties with fellow ASEAN states and the year the treaty was signed.

To conclude, operationalizing the principle of extraterritoriality in Southeast Asia may be difficult given the Southeast Asian states sensitivity to their being sovereign states as explained about. Nonetheless, there are certain positive developments within ASEAN which paves the way for an optimistic outlook as regards the possible exercise of extraterritoriality particularly in regard to dealing with non-state actors and preventing them from having access to WMD and related materials as envisioned in UN Resolution 1540.In making Southeast Asian states more receptive to the practice of extraterritoriality particularly in regard to preventing non-state actors from having access to WMD, it would be helpful to fully utilize existing mechanisms for exchanging information including the numerous platforms that bring together leaders, foreign and defense officials as well as making existing treaties such as the SEANWFZ adapt to the changed regional environment where nuclear proliferation is no longer solely the result of state action but involves non-state actors too. Indeed, the complexity of the challenge of terrorism is eventually pushing governments to become more receptive to the idea of working together, not merely in having their efforts coordinated but in finding ways to collaborate with one another.

III. ReferencesAgreement on Information Exchange and Establishment of Communication Procedures. Found at www.aseansec.org and accessed on March 15, 2011.Center for Non-proliferation Studies. 2008. Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone Treaty (Treaty of Bangkok). Found at http://cns.miis.edu/search97cgi/s97Chairman’s Statement, 15th ASEAN Regional Forum, 24 July 2008, Singapore.

and accessed March 1, 2011.Colangelo, Anthony J. 2007. “Constitutional Limits on Extraterritorial Jurisdiction: Terrorism and the Intersection of National Law and International Law”, Harvard International Law Journal Vol. 48 No 1, pp. 121-198.Joint Statement on the Commission for the Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone. 2007. Found at http://www.aseansec.org and accessed on February 15, 2011.“Navy’s Coast Watch South to be launched this November” found at http://positivenewsmedia.net and accessed on March 28, 2011.“Nuclear Disarmament, Non-Proliferation top ASEAN Ministerial Meet Agenda”, July 29, 2007 found at http://www.gov.ph/news/ and accessed on April 20, 2009.Ogilvie-White, Tanya. 2008. “Facilitating Implementation of Resolution 1540 in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific” in Lawrence Scheinman (ed.). Implementing Resolution 1540: The Role of International Organizations. United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research.Quilop, Raymund Jose G. 2008. “The Evolving Face of Nuclear Proliferation: A Challenge to Global and Regional Security”, Philippine Political Science Journal Vol 29 No 52, pp. 53-78.Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone. 1995. Found at http://www.aseansec.org and accessed on February 28, 2011.UN Security Council Resolution 1373. Found at http://www.un.org/Docs/scres/2001/sc2001.htm and accessed on March 10, 2011.UN Security Council Resolution 1540. Found at http://www.un.org/Docs/sc/unsc_resolutions04.html and accessed on March 10, 2011.“US reiterates support to RP’s Coast Watch South project” found at http://www.philstar.com and accessed on March 28, 2011.Walker, William. 2004. Weapons of Mass Destruction and International Order (Adelphi Paper 370). London: International Institute for Strategic Studies.

WMD Insights. 2008. “Resolution 1810: Progress since 1540”. Found at http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/key-issues/nuclear-weapons/issues/governance/international-coop/res-1540.htm and accessed on March 1, 2011.Global Problem Solving Book: "Complexity, Security, and Civil Society in East Asia: Foreign Policies and the Korean Peninsula." Download it free!