Introduction

See also main page: Pine Gap Joint Defence Facility

[Updated edition]

One of the enduring public concerns of the hosting of United States intelligence and military facilities in Australia, whether under the heading of “joint facilities” or otherwise, has been the possibility of a nuclear missile attack on one or more of these facilities in the event of major conflict between the United States and another nuclear power. These fears derive from an understanding that at different times over the past half century one or more of these facilities are of such importance to the US ability to conduct nuclear operations that their elimination with a long-range nuclear missile strike would be a high priority for an enemy.

Three studies are known to have been conducted on the likelihood of a nuclear attack on PIne Gap, and of its health and environmental effects.

The first, titled A preliminary appraisal of the effects on Australia of nuclear war, was produced in 1980-81 by the Office of National Assessments togeher with the Joint Intelligence Organisation at the request of the then Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser. This report was classified top secret until declassified in 2012.

The second was by the ANU strategic studies analyst Desmond Ball, published in 1983 in his collection co-edited with J.O.Langtry Civil Defence and Australia’s Security in the Nuclear Age.

The most recent, drawing substantially on Ball’s work, was published in 1985 by the Northern Territory branch of the Medical Association for the Prevention of War. Authored by Peter Tait, MAPW’s What will happen to Alice if the Bomb goes off? added considerable local context to Ball’s work, and focussed on the medical and health consequences for the town.

Since these studies were produced three decades ago, a great deal has changed, both in understanding of the health and environmental effects of nuclear attack, and in the town and surrounding regions of Alice Springs itself.

Possibilities of attack

During the Cold War, at least three bases were considered by both independent analysts and by the Australian government as highly likely Soviet missile targets if a United States – Soviet nuclear war progressed beyond a limited use of tactical (i.e. short-range, low-yield) nuclear weapons: the North West Cape naval communications base, the Nurrungar ground station for U.S. early warning satellites, and the Pine Gap signals intelligence base.

Nurrungar was closed in 2000, and replaced by the installation at Pine Gap of a remote ground station for the early warning geostationary satellites.

North West Cape’s strategic character changed in the 1980s when the United States navy replaced its Polaris missile submarines with larger submarines carrying missiles with much greater range. As a result, these missile submarines could be deployed further from the Soviet Union, particularly in the Pacific Ocean, and the very low frequency communications facility at North West Cape was no longer required for US purposes. In recent years the United States has greatly expanded its involvement with North West Cape, both for submarine communications and for space surveillance. However at this point it is not clear that negating these activities would be a high priority for a nuclear-armed adversary.

Pine Gap, on the other hand, remains a likely priority target for a Chinese missile strike in the event of a major China – United States conflict, both because of its role as a remote ground station for early warning satellites in the Defence Support Program (DSP) and Space Based Infra Red Satellite (SBIRS) systems, and its larger role as a command, control, downlink, and processing facility for US signals intelligence satellites in geo-stationary orbit. (See Richard Tanter, The “Joint Facilities” revisited – Desmond Ball, democratic debate on security, and the human interest, Special Report, Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, 12 December 2012.)

In the case of US-Russia major war, the probability of a Russian nuclear strike are much higher, given the Russian abundance of suitable missiles, and China’s relative paucity, considered against its list of priority targets.

The Australian government has long known that Pine Gap, and earlier, Nurrungar and North West Cape, were highly likely targets of a nuclear attack in the event of a major nuclear war involving the United States.

UA 1980 joint Office of National Assessments and Joint Intelligence Organisation study for the Fraser Cabinet discussed the possibilities of a northern hemisphere nuclear war, but was sanguine about the consequences for Australia:

“The radio-active fallout on Australia following a nuclear war confined to the Northern hemisphere, i.e. one in which Australian targets were not attacked, would, in the worst case likely to arise, result in an increase in environmental radiation levels up to thirty times that which occurred following the atmospheric nuclear testing by the superpowers between 1945 and 1962. Radiation levels in Australia would in this worst case, be increased in the order of 50 per cent over the level normally occurring due to cosmic rays and to radio-activity naturally occurring in rocks and in the human body.”

However, the study did concede that should the worst, albeit unlikely, case occur, all three US bases would be targets under particular circumstances:

“In the early and uncertain stages of a developing nuclear war involving the use of strategic (i.e.inter-continental) nuclear weapons, both sides might still consider that nuclear escalation could be contained and controlled. In this case, even though strategic nuclear weapons had begun to be used to a limited degree, each superpower could possibly see reciprocal advantages to the retention of facilities such as North West cape, Pine Gap and Nurrungar. We cannot, however, discount the possibility, given Soviet war-fighting doctrine – which places a high value on pre-emption – that the US facilities in Australia might be targeted relatively early in a strategic nuclear war.

“As the nuclear conflict escalated and the prospects of its containment receded, we judge that nuclear attacks on all of these facilities would probably occur. Where each side was using, or was judged likely to use, its submarine forces to strike at the opposition’s cities, the USS would rank North West cape as an important nuclear target. Since Pine Gap and Nurrungar are not an integral part of an offensive strategic nuclear weapons system, the likelihood of an attack on these installations may be somewhat lower, but such attacks cannot be excluded.”

This study was kept under Top Secret seal until it was declassified in 2012. In fact, not all senior defence planners shared the relative optimism of the 1980 report. After leaving office, the long-serving Defence minister in the Hawke and Keating governments, Kim Beazley, and the influential former Deputy Secretary of Defence, Paul Dibb, made clear that their own understandings while in office was that all three bases were accepted as being targets, and that the consequences would be vastly different from those envisaged by the 1980 report, which Dibb described in 2013 as “overly optimistic.”

Kim Beazley, a year after after leaving office in 1996 , told a parliamentary committee seminar that

“We accepted that the joint facilities were probably targets, but we accepted the risk of that for what we saw as the benefits of global stability.”

(Seminar on the ANZUS alliance, Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Parliament of Australia, 11 August 1997.)

Paul Dibb wrote in 2005 that

“We judged, for example, that the SS-11 ICBM site at Svobodny in Siberia was capable of inflicting one million instant deaths and 750,000 radiation deaths on Sydney. And you would not have wanted to live in Alice Springs, Woomera or Exmouth — or even Adelaide.”

(“America has always kept us in the loop”, The Australian, 10 September 2005)

However none of this has ever been publicly conceded by a government in office. Nor has there ever been a serious attempt to explain to people living in towns close to these targets the dangers they face. And no Australia government made a serious attempt at civil defence preparations for the populations of near these bases.

In his 2012 book on Australia’s economic and political relationship to China The Kingdom and the Quarry, the journalist David Uren reported that in a classified Force Posture Review prepared prior to the 2009 Defence white paper “defence thinking is that in the event of a conflict with the United States, China would attempt to destroy Pine Gap.”

Cabinet Office file LC 5130 containing ‘A preliminary appraisal of the effects on Australia of nuclear war’, Office of National Assessments, 8 December 1980, National Archive of Australia, barcode 7584267.

Cabinet distribution list, ‘A preliminary appraisal of the effects on Australia of nuclear war’, Office of National Assessments, 8 December 1980, National Archives of Australia.

NUCLEAR WEAPONS EFFECTS AND PINE GAP

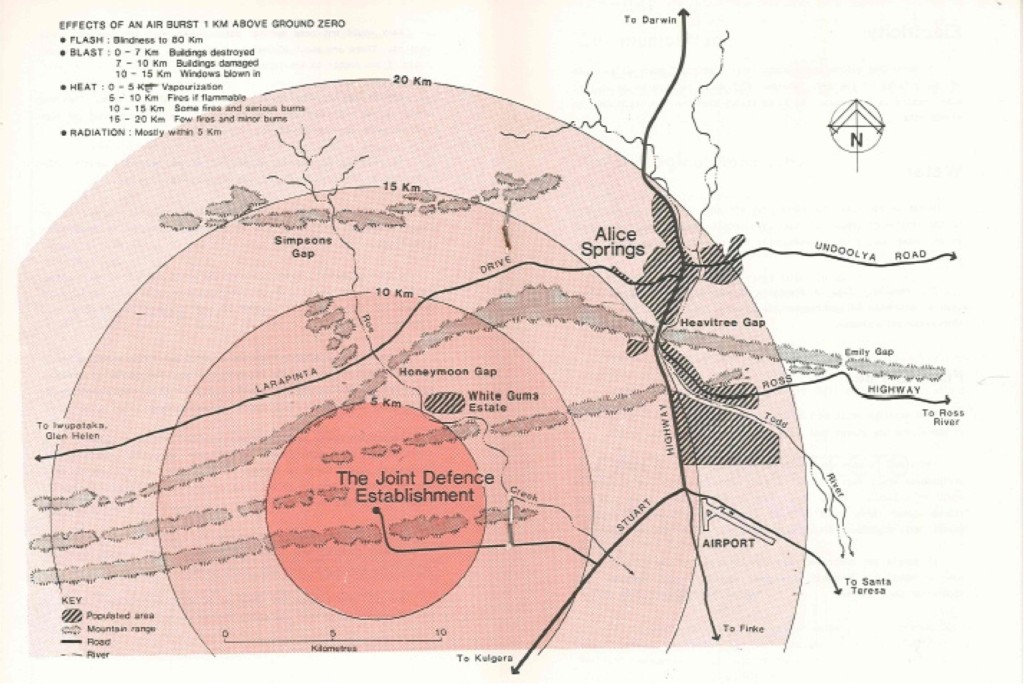

Effects of nuclear weapon attack on Pine Gap, from What will happen to Alice when the bomb goes off? Medical Association for the Prevention of War (N.T.), 1985

This NukeMap models the impact of a 1 Mt airburst strike (based on NukeMap’s preset parameters for a US Minuteman-1 ICBM), omitting fallout projections. Locations of recent housing and industrial clusters included.

Leaving to one side the global and regional effects of even limited nuclear war in terms of climate disruption, economic and food system effects, and psychosocial and political consequences, the Ball and MAPW studies provide a starting point for the local effects of a possible nuclear attack on Pine Gap, with the understanding that many elements require revision because of both contemporary deeper understanding of the health and medical consequences of nuclear explosions, and the development of Alice Springs itself.

The radiation effects of a nuclear explosion include those that are immediate, intermediate in time, and long-term, and depend on a large range of factors, including the number and size of the weapon used, the “efficiency” of the fission process in the explosion; whether the detonation is on the ground or high in the air; the time of day; the prevailing winds and other meteorological conditions; and, Ball emphasised, the adequacy of civil defence preparations and execution.

Ball’s study, which provided the foundation for the MAPW Alice Springs booklet two years later, assumed that Pine Gap could be effectively disabled – as a “soft” target – by blast effects of no more than five pound per square inch (5 psi = 34 kilopascals) peak over-pressures. “Within the five psi blast area at Hiroshima, for example, two-thirds of the buildings were destroyed and casualties were approximately 50 per cent dead and 30 per cent injured.”

Use of obsolescent Soviet SS-11 ICBMs with a 1 megaton explosive yield would be sufficient, and would allow use of more advanced and accurate weapons for other targets. Optimum blast effects of the required order would be achieved by exploding such a warhead in an airburst at about 3,000 metres – which would minimise fallout from soil and other materials lofted into the upper atmosphere by a ground burst. Standards at that time for an “acute lethal dose” of radiation (i.e. the level at which half of those exposed will die) were about 500 REMs (about 5 sieverts [sv] in current radiation dose measurements).

Ball wrote that “for airbursts of weapons in the 0.5 – 1 Mt range, the area covered by 500 REM (5 sv) could extend for 2-3 kilometers downwind from the point of detonation.” The blast effects in the town of Alice Springs – some 20 kms away, and shielded in part by the Macdonnell Ranges, would be less than 1 psi (6.8 kPa) resulting in little major damage to the town. Apart from the deaths of those among the 457 employees on duty at Pine Gap at the time, casualties from an airburst attack would be “extremely low indeed”, although fallout from winds from the south and southwest over the town could increase their numbers. (pp. 160-167)

The MAPW report provided a wider and more detailed exploration of likely effects, and a more precise and elaborated understanding of the effects of population distribution and topography. Electro-magnetic pulse effects would be felt far more widely, and would disable, for a shorter or longer period of time – or permanently – domestic and industrial electric and electronic circuits, including electricity generation, hospitals, and motorised transport. Flash effects would blind, at least temporarily, anyone looking at the blast up to 80 kms away, although most north of Heavitree Gap would be shielded from the immediate flash. Within 10 kms of the detonation, anything flammable would catch fire. “This includes the White Gums estate, parts of the airport road an Stuart Highway, a section of Larapinta Drive, the rangers’ Station at Simpson Gap and all scrub and animal life in that 10 kilometer radius”. Blast effects would follow a similar pattern out to a 15 km radius, including severe damage at the airport.

Immediate radiation effects from an airburst would depend on wind velocity and direction, but

“in any case the general level of radiation would be increased and result in contamination of resources, and increased genetic mutations. Radiation reaching the town would probably not be lethal and would arrive the day after. It might be sufficient to cause bone marrow suppression and gastrointestinal effects. This would decrease people’s resistance to infection, cause some bleeding and bruising, and nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Most people would not need life supporting treatment; a few might need symptomatic treatment.”

A groundburst, though less likely, would have markedly different radiation consequences, especially in terms of fallout, and especially if the prevailing wind came from the south or southwest towards the town proper. In that case, the town would be enveloped in a plume carrying greater than the acute lethal radiation dose, and “everybody would die within twenty four hours.” Medical capacities would be unable to cope, and “very many people would die, untreated. Large areas of Central Australia would become uninhabitable.”

The MAPW report stresses the concatenating effects of the attack, both in the immediately affected area generally south of Heavitree Gap, and in the town itself. Communications, power, sewerage, food supplies, and motorised transport would all be seriously damaged. Evacuation by the airport and the Stuart Highway to the south may well be impossible. Infections would become rife after a few days, and medical workers themselves unaffected may be unwilling or unable to enter the contaminated zone to help those in need.

Since these studies were conducted in the early 1980s, much has changed in Alice Springs and at Pine Gap. Whereas there were 454 people working at the PIne Gap base in 1978, there were more than 800 in 2013. The population of Alice Springs itself was about 16,000 in the early 1980s. In the 2011 census, the population of the Alice Springs local government area as 25,186.

However the continuing growth of the town, and its expansion west and south are increasing the number of people exposed in the event of an attack on PIne Gap. The Larapinta area to the west of the town centre has seen considerable growth in the direction of areas more vulnerable to heat, blast and radiation effects of an attack on Pine Gap. Of the 25,000 in the town as a whole, 2,306 lived in the Heavitree statistical area, south of Heavitree Gap. These figures do not include passengers and workers at the airport itself, with 640,519 regular passengers (i.e. not including military) on 6,878 flights in 2011. Nor does it include the inmates and staff at the Alice Springs Correctional Centre on the Stuart Highway, 9 kms from the base, which was built for 400 inmates, but housing at least 670 in early 2012. (Rebecca Puddy, “A `miracle’ so few die in NT jails”, The Australian, 10 January 2012). The new satellite town of Kilgariff is also to be built between Heavitree Gap and the airport, about 15 kms east of the base. All of these growth areas of Alice Springs and its surrounds are highly vulnerable in the event of an attack.

Analysis

A preliminary appraisal of the effects on Australia of nuclear war, Office of National Assessment, 8 December 1980; National Archives of Australia, barcode 7584267; declassified 2012.

Desmond Ball, “Limiting damage from Nuclear Attack”, in Desmond Ball and J.O.Langtry (eds.). Civil Defence and Australia’s Security in the Nuclear Age. (Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 1983), pp. 143-181.

Medical Association for the Prevention of War (NT), What will happen to Alice if the Bomb goes off? 1985.

Scott Campbell-Smith, ‘What if the bomb hits the base?’ Alice Springs News, 21 March 2001. http://www.alicespringsnews.com.au/0807.html

Updated: August 2017

Project coordinator: Richard Tanter

6 thoughts on “Possibilities and effects of a nuclear missile attack on Pine Gap”